fairs are known today by many different names: show, fête, festival, market, and exhibition. An ancient tradition, a fair is a temporary gathering to display and trade products, goods, and animals. From a very early date, in order to attract crowds, fairs offered entertainment in the form of musicians, acrobats, jesters, and various contests. Delicacies and dainties, such as waffles and gingerbread, were for sale in great quantities at medieval fairs; professional vendors trolled the fairgrounds with portable ovens to sell their freshly baked goods to visitors.

The modern English word “fair” originates from the archaic word “fayre” and the Latin term feria, meaning “holy day.” In medieval Europe, fairs developed as cyclical meeting places of local commerce and became, by the High Middle Ages, extremely important for long-distance and international trade. Fairs were habitually organized during the periods of saints’ feasts, in the courts of churches and abbeys, or on village greens and plains near towns. Well-known examples of age-old English fairs are those held at Westminster on St. Peter’s Day, at Smithfield on St. Bartholomew’s, and at Durham on St. Cuthbert’s Day.

A medieval fair normally began with three to eight days of preliminary work as goods were unpacked, exhibited, compared, and evaluated. The quantities for sale were revealed and prices were established, but this was a time for looking only. Next came the time for dealing, which lasted another three to eight days. The third and final stage of the fair consisted of settling and balancing accounts and arranging for credit. The layout of the fairs made comparing the quality of similar products quite easy. For instance, at the Lendit fairs, held in June on the plain between Paris and Saint-Denis, merchants from different towns (Louviers, Bernay, Lisieux, Vire, etc.) exhibited and sold their products in their own “streets.”

Among the most important fairs in medieval Europe were the Champagne fairs, a series of six events, each lasting more than six weeks, and spaced throughout the year. Originally local agricultural and stock fairs, the Champagne fairs became important in reviving the European economy as they dominated commercial relations between the Mediterranean and Northern Europe. They served as a principal market not only for textiles, leather, and fur, but also for spices. For a long time, sugar and exotic spices (saffron, pepper, cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves, and ginger), essential for creating and flavoring cakes, biscuits, and other sweets, were very expensive and therefore available only to the wealthy classes. The best places for buying such sought-after ingredients were the fairs. The fairs were also important in the spread and exchange of cultural influences such as architectural and artistic ideas and innovations from different corners of Europe. Toward the end of the medieval period, developments in transport, especially in the sea transport of heavy goods, gradually made some fairs redundant. Better markets closer to the centers of production were available and growing. The majority of the Parisian fairs, for example, were now made needless by the permanent commercial market. While some fairs disappeared, others appeared, however, and even thrived because of their specialities—a good example are the fifteenth-century fairs at Lyons focusing on silks and spices. Frankfurt fairs remained the greatest European market for German products.

Edible souvenirs like gingerbreads and other sweet treats were sold and bought at fairs throughout Europe. In England these souvenirs were commonly known under the collective name of “fairings.” At Bartholomew Fair in Smithfield, fairings of gingerbread, made from a thick mixture of honey and breadcrumbs flavored with cinnamon and pepper and sometimes colored with saffron or sander (sandalwood), were sold from 1126 to 1800. See food colorings and gingerbread. Ornamented by beautiful designs from wooden molds, the gingerbread fairings were decorated with box leaves nailed down with gilded cloves. See cookie molds and stamps. At Easter time in the northern counties of England, colored “paste eggs” were among the traditional fairings. Cornish fairings included a sweet and spicy ginger biscuit with sugar-coated almonds and caraway seeds, crystallized angelica, and macarons. See angelica.

Toward the end of the medieval period, developments in transport gradually made some fairs redundant. However, fairs took on a new life on the North American continent, where they eventually became less about trade than celebrations of regional and ethnic production. The economic significance of fairs may have changed dramatically but they are still popular today. Countless fairs are organized periodically throughout the Western world, usually concurrently with anniversaries of important local historical events, or seasonal events such as harvest times, or holidays like Christmas, and often on dedicated, traditional fairgrounds. In the United States, county fairs exhibiting the equipment, animals, sports, and recreations associated with farming are an important part of cultural life in country towns. Their larger versions, the state fairs, often including only exhibits or competitors that have won in their categories at the various local county fairs, have been held annually since 1841. Home cooks vie for top (“blue ribbon”) prizes for their pies and preserves, while fairgoers indulge in fair food both classic (cotton candy and funnel cakes) and newfangled (in Nashville, Tennessee, deep-fried Goo Goo Clusters, a milk-chocolate candy bar with caramel, marshmallow, and peanuts that is coated in batter before being fried). See cotton candy and fried dough.

fantasy worlds made of sugar and sweets are part of the folklore of societies throughout the world. These “saccharotopias” typically combine surreal and unlimited amounts of candy and other edible delicacies with a life of leisure and carefree indulgence. They are special cases of the pastoral mode, with its sunlit paradise of natural fecundity (locus amoenus) and leisure (otium). Saccharotopias often include the “natural” foods of traditional pastoral—fruit, milk, and cheese—but they focus primarily on sweets.

The earliest saccharotopia is biblical. God speaks to Moses from the burning bush, promising to free the Israelites from slavery in Egypt and to bring them to “a land flowing with milk and honey” (Exodus 3.17: אֶל־אֶ רֶץ זָב ַ ת חָל ָ ב וּדְבָֽשׁ).

In modern times, the most famous sugar fantasy is the U.S. hobo ballad “Big Rock Candy Mountain.” In the original version recorded by Harry McClintock in 1928, the world of the Big Rock Candy Mountain is a raunchy place with lakes of gin and whiskey, cigarette trees, and a hobo’s whore, as well as lemonade springs and trees full of fruit, not to mention the rock candy crag. In 1949 the folksinger Burl Ives recorded an expurgated version that became a children’s classic. Over time, other artists produced even blander lyrics: the gin disappears and whiskey turns to soda pop. Cigarette trees morph into peppermint. But the grittier Ives version is still the iconic image of America’s leading saccharotopia, the sweetness of the candy nirvana powerfully contrasted with the portrait of the hobo life:

On a summer day

In the month of May

A burly bum came hiking

Down a shady lane

Through the sugar cane

He was looking for his liking

As he roamed along

He sang a song

Of the land of milk and honey

Where a bum can stay

For many a day

And he won’t need any money

(Chorus)

Oh the buzzin’ of the bees

In the cigarette trees

Near the soda water fountain

At the lemonade springs

Where the bluebird sings

On the big rock candy mountain.

Like all saccharotopias, though, this sugary Arcadia descends from a European archetype of unknown origin, the Land of Cockaigne. That legendary place of sweet-cramming debauchery and compulsive insobriety crops up in Italy (Cuccagna), as well as Germany (Schlaraffenland or slackerland), the Low Countries (Koekange), Spain (Cucaña), and in medieval England (Cockaigne). The name has even been connected, humorously, with modern London (Cockney). According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Cockaigne’s etymology “remains obscure,” but some authorities hypothesize that it derives from words for “cake,” such as German Kuchen (the Brothers Grimm) or the Latin verb coquere, meaning “to cook.” In English, it can be traced to the fourteenth century; in German, to thirteenth-century Latin drinking songs found at Benediktbeuern, the Bavarian monastery, lyrics that have retained their vitality as texts for Orff’s Carmina Burana (Ego sum abbas Cucaniensis / et meum consilium est cum bibulis, which means “I’m the abbot of Cockaigne and I preside over a bunch of drunks”).

Perhaps the fullest account of Cockaigne survives in one of the Harley manuscripts now in the British Library. Written down in Ireland around 1330, this naughty Middle English poem celebrates a place where naked nuns swim in rivers of milk, honey, and wine. A monastery has walls made of pies, with cakes for shingles and puddings for the pegs that fasten the posts and beams.

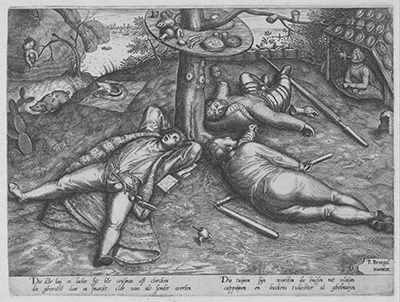

Cockaigne has inspired painters from Brueghel the Elder to Goya, who depicted a contemporary enactment of a Madrid folk ritual called cucaña, for which contestants shimmied up a very tall greased pole. Successful climbers were rewarded with an edible prize at the top. There are photographs of a similar cuccagna pole in Italy.

An entirely separate “Cockaigne” tradition arose in the Spanish Empire in the sixteenth century, in the Andean town that Pizarro called Jauja and established as the first capital of Peru in 1534. Before their defeat, the Incas had stored a vast amount of food in Jauja, which thereafter became famous throughout Spanish America as a proverbial paradise of easy living. Even today in Mexico and its cultural hinterland across the U.S. border, the city of Jauja, la ciudad de Jauja, lives on in folklore as a mythic Shangri-La. The best evidence of this is a corrido of the same name. This popular Chicano song celebrates churches made of sugar, caramel friars, molasses acolytes, and side altars of honey. It can be heard on YouTube.

The legendary Land of Cockaigne, with its superabundant food and drink, has inspired artists for centuries. This engraving, attributed to the Netherlandish painter Pieter van der Heyden, was completed sometime after 1570. the metropolitan museum of art, harris brisbane dick fund, 1926

Farmer, Fannie (1857–1915), was one of America’s most esteemed cooking teachers and authors at the turn of the twentieth century. Renowned for her scientific approach to cooking and strict precision in measuring ingredients, she published her first book The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book in 1896. See measurement. It was reprinted countless times. Farmer also took great pride in her courses in sickroom cookery. She wrote Food and Cookery for the Sick and Convalescent in 1904 and lectured at Harvard Medical School.

Farmer also had a whimsical side and a notable sweet tooth. Her works abound with cakes, cookies, pies, pastries, candies, ice creams, and puddings. The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book includes one of the first recipes for so-called brownies. They were not made with chocolate, but rather flavored with molasses, baked in individual shallow cake tins, and garnished with pecans. See brownies. She made almond and cinnamon cookies shaped like horseshoes and studded with chocolate frosting nails. She sent her rolled wafer cookies to the table with ribbons around them and molded puddings into heart shapes for Valentine’s Day. One of her Christmas desserts was a dish of ice cream covered with crushed macarons and topped with a crepe-paper-clad doll. In her December 1905 column for The Woman’s Home Companion she wrote excitedly that she hoped it would “make many an eye twinkle at the Christmas dinner.”

Farmer never met a marshmallow she did not like or could not mix into ice cream, frosting, or, especially, gelatin. Her salads were often as sweet as desserts. She gave the world the famous (or infamous) ginger ale salad. To make it, she added ginger ale to gelatin and then mixed in chopped cherries, celery, apples, and pineapple. See gelatin and marshmallows.

Remembered today for her stern insistence on level measurements, Farmer was also the woman who introduced ices and ice creams in the 1896 Boston Cooking-School Cook Book by writing, “How cooling, refreshing, and nourishing, when properly taken, and of what inestimable value in the sickroom!”

In this famous photograph, the Boston Cooking School principal Fannie Farmer (1857–1915) holds a measuring cup to a student, as if to reinforce her reputation as the “Mother of Level Measurements.” © bettmann / corbis

See also christmas; ice cream; icing; pudding; and valentine’s day.

fermentation is a process by which yeasts or bacteria produce alcohol, lactic acid, acetic acid, and other chemical byproducts as they metabolize sugars derived from varied sources. All sugars can be used as substrates for fermentation.

Alcohol Fermentation

By far the most widespread form of fermentation is the production of alcohol. Alcoholic beverages are produced by the action of yeasts (primarily Saccharomyces cerevisiae but also many others) on sugars found in honey, grapes, apples, and many other fruits, as well as cacti, tree saps, grains, starchy tubers, and milk. Indigenous people of most regions of the world developed distinctive alcoholic beverages made from available local carbohydrate sources. Simple carbohydrates ferment directly into alcohol. Yeasts are generally present on sugar-rich substrates, and fermentation will generally proceed spontaneously. For instance, raw honey diluted with water will inevitably begin to ferment, as will freshly pressed fruit juice.

In contrast, complex carbohydrates must first be broken down (by enzymatic processes) into simple sugars that will ferment into alcohol. Thus, it is always more technically difficult to produce beers and other grain- or starchy tuber-based beverages than wines and other alcoholic beverages made from fruits or other simple sugars. In the Western tradition of beer making, germination of grains, known as malting, produces such enzymes. This is the process used in making hopped barley beers and ales, as well as Egyptian bouza, African sorghum and millet beers, Central American corn beers, and many others. In the Asian tradition, the primary source of these enzymes is molds (primarily Aspergillus spp. but also Rhizopus spp.) grown on grains, such as Japanese kōji, Chinese chu, Korean nuruk, Indonesian ragi, Nepalese marcha, and others. The third source of such enzymes, generally regarded as the most ancient, is human saliva; chewed grain beverages, such as chicha, made from corn in the Andes Mountains of South America, continue to be produced in several different parts of the world.

Distillation is a process that concentrates alcohol (or other volatile substances). Only fermentation can create alcohol, and distillation can only concentrate alcohol that has already been fermented. Any type of fermented alcohol may be distilled. The process takes place in an apparatus known as a still. Distillation evaporates and then condenses the fermented alcohol, thanks to the different boiling temperatures of different substances. Alcohol boils at 173°F (78°C), whereas water boils at 212°F (100°C). So when fermented alcohol—a mixture of alcohol and water—is heated, the vapors contain proportionately more alcohol than the liquid, as does the resulting liquid when the vapors are cooled. With repeated runs through the still, a purer and purer product results.

Lactic Acid Fermentation

Another widespread form of fermentation is the metabolism of sugars into lactic acid by lactic acid bacteria. Many varied foods and beverages are products of this process: sauerkraut, kimchi, and other fermented pickles are lactic acid fermentations, in which plant sugars are metabolized into lactic acid by bacteria found on all plant life. Yogurt, kefir, and many cheeses also rely on lactic acid fermentation of milk sugar lactose. Yogurt and kefir are cultured by specific microbial communities that define the ferments, but lactic acid bacteria are present in all raw milk and will spontaneously clabber (sour) the milk if it is left unrefrigerated. Grains, too, will yield lactic acid after spontaneous fermentation.

Acetic Acid Fermentation

Another important metabolic product of the fermentation of sugars is acetic acid, more commonly known as vinegar. Acetic acid is not metabolized directly from sugars, but rather from alcohol. Thus, the fermentation of acetic acid from sugars is a two-stage process: first, the fermentation of sugars into alcohol; then a distinct microbial process in which the alcohol is converted into acetic acid. Vinegar can be made from any fermented alcohol or solution of fermentable sugars.

The bacteria that metabolize alcohol into acetic acid are known as Acetobacter. Acetobacter are aerobic organisms that can convert alcohol into acetic acid only in the presence of oxygen. This is why alcoholic beverages are typically fermented under conditions designed to exclude air, to avoid conversion of alcohol into acetic acid. But when acetic acid is the desired outcome, a vessel with a broad surface area is used to maximize contact with oxygen.

Mixed Fermentation

Many ferments involve some combination of alcoholic, lactic, and acetic fermentations. Until Louis Pasteur’s 1860s research isolating yeast and other fermentation organisms, microorganisms always existed in communities, and many—arguably all—traditional ferments have involved more than a single type of fermentation. For instance, sourdough breads (and all bread until the isolation of yeast) are risen by a combination of yeasts and lactic acid bacteria. Similarly, in traditional fermented alcoholic beverages that rely on wild yeasts rather than isolated pure strains, the yeasts are always accompanied by lactic acid bacteria, and the products include not only alcohol but also lactic acid.

See also fruit; honey; malt syrup; sap; and yogurt.

festivals, unlike quotidian rituals of blessing food or saying grace at the table to honor what we eat, highlight foods and dishes that reflect a community’s religious, social, and cultural roots.

In Europe’s traditionally Catholic countries, saints’ days often have their own festivals, which are associated with particular sweets. In Sicily, to celebrate the 13 December holiday of Santa Lucia, a wheat and ricotta cream dish called cuccìa (related to the word for grain) is traditionally enjoyed. This practice has its roots in the seventeenth century, when residents of Palermo suffering from famine prayed to the Sicilian saint Santa Lucia, who hailed from Siracusa. When a boat carrying wheat arrived, the grain was quickly boiled instead of being ground into flour for pasta, and it was eaten with the local ricotta cheese. The ricotta cream version of cuccìa is specific to Sicily, where pasta and bread are banned on the holiday in commemoration of this historical event. In Sweden, St. Lucia Day is celebrated with saffron buns in assorted shapes (Lussekatter), whose golden hue brings light to the dark December days.

Christmas Eve in Provence is marked by the meatless gros souper (big supper), which is consumed before midnight mass. An important aspect of the meal is les treize desserts de Noël—the 13 desserts of Christmas, which symbolically represent Jesus and his 12 apostles. Thirteen desserts, including nougat, mendiants (dried fruit confections), and various fruits, are presented; tradition holds that each guest must taste at least one. See christmas and nougat.

In India, foods are ritually tied to the country’s many festivals. The Hindu celebration of Diwali is very sweets oriented, with laddu made of chickpea flour, cardamom, sugar, and ghee one of the holiday’s most typical offerings. See diwali and laddu. Jalebi is a popular dessert made of a chickpea-flour batter fried until crisp and then drenched in a sugar syrup flavored with saffron and cardamom. Children enjoy candy toys during Diwali. Modaka, said to be the elephant-headed deity Ganesh’s favorite treat, are small dumplings stuffed with jaggery (unrefined sugar) and coconut, either steamed or fried. Tradition calls for 21 modaka to be made as an offering during the Chaturthi festival in August. See modaka.

China’s most popular sweet is the mooncake, which although tied to the Mid-Autumn Festival (sometimes called the Mooncake Festival), has many variations. The pastry is typically stuffed with lotus seed or red azuki bean paste; it sometimes contains a salted duck egg yolk, which symbolizes the full moon. The dessert is labor-intensive and almost always prepared commercially rather than at home. Mooncakes are also associated with festivals in Indonesia, Japan, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, where for the New Year, Tet Nguyen Dan (or simply Tet) mooncakes are part of offerings made to the kitchen god Ong Tao. Families sometimes smear honey over the mouth of an image of Ong Tao to guarantee that he will say only pleasant or sweet things during the coming year. See mooncake.

Fruit Festivals

Many festivals are based on seasonal fruits, especially strawberries, celebrations of which abound in North America and Europe. See fruit. Perhaps the most famous in the United States is held in Ponchatoula, Louisiana, which bills itself as the Strawberry Capital of the World. Bayou musicians perform at the city’s three-day Strawberry Festival in mid-April, and there is a Strawberry Strut race, a parade and auction, and a college scholarship for each year’s Strawberry Queen. Strawberries are consumed deep-fried, chocolate-dipped, blended in daiquiris, and by the dozens in a strawberry-eating contest. The festival is preceded by a Strawberry Ball at the end of March and followed by a Strawberry King and Queen Pageant and Grand Marshall Coronation at the end of May.

France’s best-known salute to the strawberry takes place in Beaulieu-sur-Dordogne on the second Sunday of May. The highlight is a giant strawberry tart—as large as 26 feet across and containing as many as 1,700 pounds of strawberries—made by local bakers and served to all festival attendees.

Italy also has a variety of strawberry festivals. The Sagra delle fragole in Piedmont’s hamlet of Fosseno features a risotto alle fragole. In Lazio, the town of Nemi celebrates fragoline di bosco, prized wild strawberries. During the festival, local girls in traditional dress walk through the crowds, handing out the small berries.

In Italy’s Alto Adige (South Tyrol), apples are one of the leading crops. The three-day Bolzano Gourmet Festival, held in late May, showcases apples that have received the Protected Geographical Status certificate of Mela Alto Adige IGP/Südtiroler Apfel (Alto Adige and South Tyrol Apple). The event features educational programming and workshops in an apple orchard, as well as culinary demonstrations by top local chefs.

Confectionery Festivals

Europe’s most popular chocolate festival is held in Perugia, Italy, in mid-October, where the city’s famous Baci chocolates are prominently featured. Perugia’s proximity to Spoleto and its world-renowned Spoleto Festival of culture may account for the Chocolate Festival’s inclusion of exhibits, songs, and plays about chocolate.

Food fights are a feature of many culinary festivals in Spain. When the participants in La Merengada in Vilanova i la Geltrú—part of Carnival celebrations in late February or early March—run out of meringue pies to throw at each other, they substitute candies. A similar rite occurs in many Andalusian towns, including the regional capital, Seville, which holds the Cabalgata de Reyes Magos (Arrival of the Magi) festival on 23 December. Participants throw candies from floats, as they do during many Carnival festivals throughout the world. See carnival.

See also china; chinese new year; france; holiday sweets; india; italy; scandinavia; southeast asia; spain; and united states.

Fig Newtons, trademarked by Nabisco, are popular bar cookies made of fig jam encased in cake-like pastry. They are surprisingly similar to the traditional fig rolls and maʾamoul, a sweet composed of shortbread pastry stuffed with figs, nuts, and other dried fruits, still popular today across the Middle East.

The technology that made Fig Newtons commercially viable in the United States has been subject to competing claims. One insists that Ohioan Charles Roser invented a machine around 1891 that allowed the cookies to be mass-produced by funneling the jam and the cookie dough separately but simultaneously. The other asserts that James Henry Mitchell of Philadelphia invented the cookie in 1891 when he came up with a duplex dough-sheeting machine and funnels.

Fig Newton cookies have been popular ever since their introduction in 1891, but in 2012 they were recast simply as “Newtons” to allow for an expanded line of fillings and to eliminate associations with what the manufacturer, Nabisco, feared was a “geriatric” fruit. photograph by evan amos

Folklore maintains that the cookie was named after Sir Isaac Newton, but its more likely eponym is the Boston suburb of Newton. The Kennedy Biscuit Works of Cambridgeport, Massachusetts—the first company to produce Fig Newtons commercially, in 1891, soon after the machinery had been perfected—commonly named its products after nearby towns. Within a decade, following a massive nationwide merger of biscuit companies, Nabisco acquired the Biscuit Works. Today, the cookies are known simply as Newtons and encompass several varieties: crisp Fruit Thins, a whole-grain version, and fruit fillings other than fig. The 16th of January is National Fig Newton Day in the United States.

See also fruit paste and gastris.

filo is the Greek name for the paper-thin pastry known as yuf ka in Turkish. It is made of durum wheat flour with a high gluten content, enabling it to be rolled or stretched very thin without tearing. The other ingredients are usually just water and salt, although some recipes may also include eggs or yogurt. Filo is rolled out in large circles using a long, thin rolling pin called an oklava in Turkish. Ottoman pastry chefs developed a faster method, first recorded in 1838, by which each walnut-sized ball of pastry is rolled to a saucer-sized circle, then piled up 10 at a time with starch sprinkled between each layer, and the whole pile rolled out simultaneously. See baklava.

When made at home for immediate consumption, filo sheets are used raw, but professionals half-cook them very briefly on a domed griddle, then dip them in water, and hang them up to dry, a process that enables the daily batch to be piled up without sticking together. Factory-rolled filo is thick and inflexible compared to the hand-rolled variety, and in Turkey it is used only as a last resort. In most urban neighborhoods, specialty shops exist where the paper-thin sheets are freshly rolled daily. In Greece there are no longer any artisans producing hand-rolled filo commercially, so consumers must rely on machine-rolled sheets.

In the past filo rolling was something that most country-bred Turkish boys learned to master, as we learn from a Turkish cookery book written in 1900 by an army officer named Maḥmūd Nedim for unmarried fellow officers. He writes that if his readers cannot roll out pastry themselves they should ask one of the soldiers, “most of whom know how to make yuf ka.”

Flatbreads are of great antiquity in western Asia, but the very thin filo appears to be a Turkic innovation originating in Central Asia. Medieval Arab recipes often use the Turkish term tutmaç for this type of thin pastry. The eleventh-century Turkish-Arabic dictionary Dīwān luġāt at-turk written by Maḥmūd of Kashgar mentions yufka several times, including a dish made of filo folded and fried in butter and one variety of dough (yalaci yuvga) so fragile it crumbles at the touch. Since the Turks were a nomadic people, a type of bread that could be rolled out and cooked on a portable griddle in a matter of minutes was more practical than leavened bread, which needed time to rise and an oven for baking. In 1433 the French pilgrim Bertrandon de la Brocquière (1400–1459) encountered Turcoman nomads in the mountains of southern Turkey, who offered him fresh filo with yogurt, cheese, and grapes. The filo was made so quickly that Brocquière declared, “They make two of their cakes sooner than a waferman can make one wafer.”

In addition to being eaten as bread with food, filo can be wrapped, folded, and layered with any number of savory or sweet fillings, and fried, baked, or cooked on a griddle. This versatility has given rise to a vast category of dishes throughout Central Asia, the Middle East, and the Balkans, from the simplest version described by Brocquière, who noted that the nomads “fold them up as grocers do their papers for spices, and eat them filled with the curdled milk [yogurt],” to baklava with 80 to 100 layers.

See also greece and cyprus; middle east; and turkey.

See small cakes.

See egg yolk sweets; portugal; and portugal’s influence in asia.

flan (pudím) is a word much in use when it comes to sweets, but as defined here, the words “flan” or “pudím” (pudding) are restricted to a dessert that is basically a firm custard made with considerable variation. As a custard dessert, flan is most often associated with Spain and the countries it colonized and traded with during the early era of sea exploration. The terms pudím, pudim, or flan pudim are also used in Portuguese-speaking countries. French versions of flan are called crème renversée and crème caramel; in Italy, it is known as crema caramella. In Brazil, quindim, quindin, and pudim de leite are versions of flan pudim. In Catalan, “flan” is spelled as flam. In parts of South America and the Caribbean, quesillo is interchanged with the word “flan.” The Japanese call flan purin, an abbreviation of pudingu.

The signature of classic flan is caramel. Sugar, or sugar syrup, is caramelized and used to coat the cooking mold. See stages of sugar syrup. The caramel hardens quickly. The custard mixture is added and the mold or molds are set in an insulating hot water bath (bain-marie) to cook in the oven or on top of the stove. The water moderates the temperature and keeps the edges of the custard from overcooking before the center is done. Steaming also works. Cooked flans must be removed from hot water or heat at once to avoid overcooking.

Flan may be served warm from the container in which it cooks, but typically flan is chilled to reach its maximum gentle, tender firmness—a solid state of varying density, depending on the ingredients used and their proportional relationship. As the flan cools, the caramel, which began to melt during the cooking process, continues to liquefy. When the flan is inverted from the mold, some of the caramel has sunk into the custard base, giving what is now the top its brown color. The liquid caramel helps the flan slip free and pools as a thin sauce around the dessert. Any caramel remaining in the mold usually has to be soaked free.

Custard, the essence of flan, has been recorded since Roman times, most astutely by Apicius in the first century. See custard. Flan custard is a combination of eggs that are beaten and blended with milk or cream (or with another liquid, purée, or even butter). For desserts, the custard is sweetened and usually flavored. The eggs create a sort of protein sponge that firms around the liquid to make it set or become semi-solid when cooked. If overcooked, the sponge tightens and breaks or curdles into liquid and rubbery lumps (a reaction called syneresis).

The number of eggs can vary, but one or two are needed at a minimum, or two to three egg yolks per cup of milk or liquid, plus sugar. Yolks make a thicker, more richly flavored custard, whereas whites deliver the most fragile and delicate one. Packaged flan or crème caramel mixes may not contain eggs, nor do the mixes require baking. Nonfat and lowfat milk with minimum eggs or whites make more delicate custards that firm at lower temperatures; richer cream and more yolks make custards with the smoothest and most unctuous impact. Recipes with a French heritage often call for extensively beating eggs and sugar, but beating just enough to blend thoroughly suffices. Straining is a superfluous effort. The amount of sugar influences how hot the custard must be to thicken, coagulate, or clot, and of course it influences the taste. The more sugar, the hotter the custard can get before breaking. Acid, such as lemon or fruit juice, causes custard to thicken at lower temperatures, but sugar counterbalances this.

Heating the milk before adding it to the eggs speeds cooking and also alters the milk proteins so that they form a thinner skin on the surface of the cold flan. Sweetened condensed milk, used particularly in Mexico, Central and South America, the Caribbean, and other hot-climate countries, dramatically raises the temperature to which flan can be heated, making it less prone to overcooking, and produces an even denser texture. See sweetened condensed milk. Cream cheese, another ingredient often used, adds more density, stability, and flavor to the flan. The best way to determine when flan is set, or done, is to shake the container gently: it is ready when the mixture jiggles just a little in the center. The old test of inserting a knife, to see if it comes out clean, works best when the custard is overcooked or on the verge of being so.

Flan welcomes flavors, especially vanilla. See vanilla. The name often indicates the distinguishing ingredient: flan de coco (coconut), flan de leche (milk), flan de queso (cheese), pudím de piña (pineapple). Chocolate, coffee, and cinnamon flavors are popular. Pumpkin, guava, and apple purées—with or without milk—that are bound with eggs are classified as flans and may not include caramel. Some flans (puddings) are considered as such only in that they are unmolded; this type of flan may be based on fruit purée or juice firmed by gelatin.

See also flan (tart).

flan (tart) is a simple open tart with a pastry crust filled with fruit, flavored creams, or any number of other ingredients. It is not to be confused with the custard-type dessert also known as flan (the word “flan” is derived from “flado,” meaning a round, flat object). See flan (pudím). Flans can be sweet or savory (a quiche is a flan). Dessert flans may be made with a sweet shortcrust (pâte sucrée), a shortcrust (pâte brisée), or even puff pastry. See pastry, puff. Special metal flan rings are bottomless so that the ring can be lifted straight up from the cooked tart before serving without disturbing its appearance. The flan can also be made in a tart pan with fluted sides and a removable flat metal disk on the bottom. After it is baked, the flan, supported from underneath by the metal disk, can be pushed up and out of the ring and placed on a serving plate. In both cases, the flan is perfectly formed and freestanding when served. For fruit flans, the fruit and the molded pastry can be cooked separately and then combined, or cut fruit can be arranged in the pastry shell before cooking.

In his Livre de pâtisserie (1873), Jules Gouffé gives a recipe for Flans de Crème de Frangipane Meringuée, in which the bottom of the pastry crust is covered with frangipane flavored with sugar, crushed macarons, and orange flower water. See frangipane. When the filled pastry has finished baking, meringue is piped over the top and the flan is put back into the oven until the meringue colors slightly. Gouffé then garnishes the dessert with preserved cherries.

Florentines are rich, round cookies made of caramelized toasted nuts and candied fruit, baked until golden brown, and then coated with dark chocolate. The contrasting textures and tastes make this pastry so special. Florentines are enormously popular worldwide but, like the savory dish “Eggs Florentine”, they seem to have very little to do with the city of Florence. Unfortunately, disinformation often travels fast, and many sources erroneously claim that these delicious cookies originated in Florence. It is possible that the “Florentine” attribution arose from the Medici sisters’ influential presence in France, since they originally hailed from Florence.

Florentine confectioners, especially Caffè Gilli, date the production of this sweet speciality only to the early twentieth century, when they were making fiorentine—small (3 centimeters), hand-made chocolate pastilles (dark, milk, or white) topped with candied fruit, pistachios, or almonds. These ingredients are quite common to many Tuscan favorites, such as cavallucci, made with nuts, flour, spices, and honey, and panforte, made with candied fruit and nuts, so it is not surprising that they would show up in a new kind of cookie. However, these baked goods have little other resemblance to the Florentine cookie (neither has a chocolate topping, for instance).

In many English-speaking countries, such as Australia or South Africa, different versions of Florentines may be found that include ingredients like condensed milk, corn flakes, cranberries, and ginger. The well-known British chef Nigel Slater has offered recipes for Florentines with dried cranberries or poached pears in his food column in the Observer; he recommends hand chopping the candied peel and using only the finest dark chocolate.

Today, Florentines have finally come “home” to Italy. Numerous recipes can be found online, and articles about them are published in women’s magazines. These recipes generally follow the classic version made with sugar, cream, butter, candied fruit, chopped and slivered almonds, and dark chocolate.

See also italy.

flour is the refined product that results from the milling of grain. Any type of grain can be milled into flours that range in consistency from coarse to fine, but for the purposes of baking, wheat flour is the most widely used. Whole-wheat flour is milled from the whole grain of wheat, also known as the wheat berry, which is composed of the bran, germ, and endosperm. The bran layer—the hard outer shell of the kernel—contains most of the fiber. The germ is the nutrient-rich embryo that, when cultivated, sprouts into a wheat plant. The endosperm is the largest part of the grain and is mostly starch. The flavor of whole-wheat flour is strong and distinctive. Refined white flours, by contrast, are made from only the endosperm. Since the sixteenth century white flour was sought out by the elite, in part because it was the most expensive, and fine pastry chefs favored white flour because it yielded the most delicate pastries and cakes. Only recently has whole-grain flour, long despised as peasant food, become something desirable, even trendy.

Processing

In the past, flour was stone ground, a slow milling process that causes less friction and heat, thereby preserving more of the nutrients in the wheat. With the invention of roller milling in Hungary in the mid-nineteenth century, and its spread throughout Europe and the United States in the late nineteenth century, stone-ground flour, especially in the United States, was relegated to a health-food fringe. Massive mills with high-temperature, high-speed steel rollers came to rule the industry. Although this high-speed process creates a much finer flour, it destroys many of the nutrients in the grain. Furthermore, while stone-ground flour is generally aged to improve its baking properties, industrial mills skip the expensive aging process. American mills generally bleach the flour with chemicals, including organic peroxides, nitrogen dioxide, chlorine, chlorine dioxide, and azodicarbonamide. (Japan stopped bleaching flour about 30 years ago, and the use of chlorine, bromates, and peroxides is not permitted in the European Union.) Bleaching has a negative effect on baking, as it toughens the dough, making it brittle, dry, and more difficult to work with.

Protein Content

Wheat flours are distinguished by how they are milled, the type of wheat, how it is grown, and the time of harvest. All of this affects the protein content, which in turn correlates to the amount of gluten in any given flour. Gluten helps create structure and determines texture in the final baked good. Flours with low protein contents produce crumbly tarts and tender, toothsome cakes, while higher protein results in hearty breads with a chewy crust. When the flour is moistened and then mixed or kneaded, the gluten is activated. The small air pockets that form are inflated by gases released by the leavening agent, which causes the dough to expand or rise. The more the dough is mixed or kneaded, the more the gluten develops. For this reason, batter cakes and cookie doughs are mixed only briefly, as overmixing causes the dough to toughen and dry out.

For light and airy cakes with delicate crumb, low-protein flour, either cake flour or pastry flour, is optimal. Most cookies use all-purpose flour with its moderate protein level to allow the dough to be rolled out. Pie doughs also require all-purpose flour so that they can be rolled out into large disks without breaking or crumbling. Shortbread or other butter-rich doughs that yield a fine, sandy crumb in cookies or tarts require lower-protein flours. Elastic doughs such as puff pastry need flour with more protein so that the dough will be firm enough to roll out and layer with butter. See cake; laminated doughs; pie dough; pastry, puff; rolled cookies; and shortbread.

White flour should be stored in a cool, dry area in an airtight container. Because it contains bran, whole-wheat flour easily turns rancid, and its flavor will dissipate. It should be stored in a cool, dry place for up to four months, or refrigerated or frozen for longer storage. The name given to the flour generally indicates how it is intended to be used.

Types of Wheat Flour

Bread flour is a strong flour, meaning that it has a high gluten content, usually around 13 to 16 percent protein. A handful of bread flour feels coarse and is slightly off-white in color. Bread flour is used for making crusty breads and rolls, pizza dough, and similar products.

All-purpose flour is formulated to have a medium gluten content of 10 to 12 percent, which makes it a good middle-of-the-road choice for a wide range of baking, from crusty breads to fine cakes and pastries. Even so, most professional bakers avoid all-purpose flour, preferring instead to use bread flour, cake flour, or pastry flour, depending on what they are baking.

Pastry flour contains about 8 to 10 percent protein. It can be used for biscuits, muffins, cookies, pie doughs, and softer yeast doughs. It is slightly more off-white in color than cake flour.

Cake flour, made from soft wheat, is slightly less strong than pastry flour, with a protein content of only 7.5 to 9 percent. Its texture is visibly finer than that of bread flour, and it is much whiter in color. Its fine, soft consistency makes it preferable for tender cakes and pastries.

Self-rising flour, all-purpose flour with measured amounts of baking powder and salt, is a commercial product created as a convenience for home cooks. It must be used very fresh, because when the flour is stored in the pantry, the baking powder quickly loses its effectiveness.

White whole-wheat flour is about 13 percent protein. It comes from a type of wheat that has no major genes for bran color. The bran of white wheat is not only lighter in color but also milder in flavor, making white whole wheat more appealing to those accustomed to the taste of refined flour. Its milder flavor also means that products made with white wheat require less added sweetener to attain the same level of perceived sweetness.

Whole-wheat pastry flour, or graham flour, is milled from low-protein soft wheat, with about 9 percent protein.

Regular whole-wheat flour, milled from hard red wheat, has a protein content of 14 percent. It is used in cookies, crusts, and creamed or batter cakes.

Gluten-free all-purpose flour was developed for those with gluten sensitivity. The flour can be used for cakes, cookies, breads, and breakfast items such as muffins, pancakes, and waffles. Unlike wheat flour, gluten-free flours are composed of a wide range of ingredients and vary greatly. The major difference is found in the first ingredient listed on the package label, which may be cornstarch, white and brown rice flours, or garbanzo bean flour. Each has a completely different flavor and effect on baked products, so manufacturer’s instructions should be followed for each brand. The flours may also contain milk powder, tapioca flour, potato starch, xanthan gum, potato starch, tapioca flour, sorghum flour, and fava flour. Gluten-free baked goods do not keep well, so they are best eaten the same day they are baked.

Although it is generally safe to use pastry and cake flour interchangeably, it can be tricky to substitute flours with different protein contents. All-purpose flour can be used for most pastry doughs, but if a finer product is desired, its protein content can be reduced by removing two tablespoons from a cup of flour and replacing them with two tablespoons of sifted cornstarch. Conversely, the protein content of all-purpose flour can be increased by replacing two tablespoons of flour per cup with vital wheat gluten.

See also breads, sweet; chemical leaveners; muffins; and pancakes.

flower waters, produced by steeping petals in water or by distillation, have been used since ancient times in medicine, perfumes, and cosmetics. The waters are also important in the kitchen as luxury flavorings, almost magically transforming food by imbuing a delicate fragrance, especially to sweet dishes. Rosewater and orange flower water are the best known, but other flowers can be used, such as screwpine, jasmine, rose geraniums, and ylang-ylang. Because their flavor can be intense, they should be used sparingly.

Rosewater

This flower water can be made from any sweet scented roses. The most famous is the ancient damask rose, but the cabbage rose, French rose, and musk rose are also used. Eglantine flower water from a wild rose, sometimes called sweet briar, is particularly popular in Tunisia. The ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans extracted fragrance by steeping rose petals in water, oil, or alcohol. Although water distillation is still traditionally used in many Eastern countries, nowadays steam distillation is often the preferred method. Here, for instance, is how rosewater is made in Afghanistan today: The blooms are picked fresh in the cool, early hours of the morning. A large copper pot or cauldron is filled with water. The petals are added (the amount of water is usually about twice the weight of the petals), and the water is brought to a gentle boil. The pot is covered with a type of copper dome from which an attached pipe or tube leads to a glass bottle, into which the pipe neatly fits. Everything is sealed with dough to prevent the fragrant steam from escaping. The steam rises into the dome, and as it travels down the pipe, it is cooled by cold water, causing the steam to condense into droplets. The droplets travel along the pipe, and slowly the fragrant rosewater drips into the bottle. (Sometimes this rosewater is poured into another pot and slightly warmed again, then left to stand until a thin film of oil forms on the surface. The oil is skimmed off to make atr [attar], or oil of roses.) Orange flower water is traditionally made in much the same way.

The technique of distilling rosewater probably evolved in the third and fourth centuries c.e. in Mesopotamia. By the ninth century Persia was distilling rosewater on a large scale, and it was much used there and in neighboring regions. During the Golden Age of Islam in tenth-century Baghdad, famous for its lavish and sumptuous cuisine, rosewater was used extensively in sweet and savory dishes. See baghdad.

The Ottoman Turks used rosewater to add fragrance to desserts, pastries (such as baklava), and sweetmeats (such as lokum), as well as to syrups and sherbets. The Turks introduced roses to Bulgaria, where the Valley of the Roses at Kazanluk is famous for its rosewater and rose petal jams. The use of rosewater spread to Europe via the Crusaders. In Elizabethan England, rosewater was used to flavor butter and sugar paste.

Colonial Americans, too, added rosewater to confectionery and desserts. Martha Washington’s seventeenth-century Booke of Sweetmeats uses rosewater extensively in the recipes. Eliza Leslie (1857) pounded almonds for her almond pudding with “a few drops of rose-water to make them light and preserve their whiteness.” Rosewater was added to syrups for use in beverages and also in savory dishes such as chicken pies and spinach. It was often purchased from the Shakers, a religious sect renowned for the purity of their products and who themselves fragranced their apple pie with it.

Rosewater today is used extensively throughout the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, Central Asia, Turkey, and North Africa. It subtly perfumes biscuits, pastries, jelabi, firni, rice puddings such as kheer and shola, ice creams, faluda, and halvah, as well as drinks such as sherbets and sweet lassi, and sometimes savory rice dishes for festive occasions.

In the West adding a little rosewater to creams, sorbets, mousses, and jellies or sprinkling it over fruits, especially strawberries, transforms these dishes into something exotic.

Orange Flower Water

Sometimes called orange blossom water, orange flower water is distilled from the blossoms of bitter orange trees such as Seville orange and bergamot. It originated in the Middle East, where it is still produced, especially in Morocco and Lebanon. The water is used to add fragrance to syrups, pastries, sweets, and desserts. A teaspoon of orange flower water added to a coffee cup of boiling water, sometimes sweetened with sugar, is called “white coffee.” A few drops added to sweetened cool water make a soothing infusion that is often given to children at bedtime. Moroccans frequently add orange flower water to tagines and sometimes sprinkle it over salads.

In the sixteenth century in the south of France, bitter oranges were widely cultivated to make orange flower water, initially for use in the perfume industry. By the seventeenth century in Europe, the water was flavoring almond cakes, rich seed cakes, biscuits, dessert creams, and custards. In Britain it was often used as an alternative to rosewater and added to desserts such as trifles and fools.

Orange flower water flavored capillaire, a fashionable nineteenth-century drink whose syrup was originally infused with maidenhair fern. It was also a key ingredient in orgeat, initially a beverage and later a syrup used to sweeten other beverages. American food writer Mary Randolph (1828) called orgeat “a necessary refreshment at all parties.” Martha Washington’s Booke of Sweetmeats uses orange flower water in a recipe for Hunny Combe Cakes.

Orange flower water is an ingredient in the famous New Orleans cocktail Ramos Gin Fizz and in the Mardi Gras orange cake. In France it flavors madeleines and is added to the turrón (nougat) of Spain. Further afield, it is added to little wedding cakes and to pan de muerto in Mexico.

Kewra Water

Sometimes known as kewda, kewra water is extracted from the flowers of the screwpine (Pandanus odorifer). See pandanus. It is similar to rosewater and is often used as an alternative or mixed with it.

India is a major producer of kewra, 90 percent of which grows in the state of Odisha. Its soft, sweet scent is prized for use in Indian and Sri Lankan cooking, mainly for desserts and sweets such as kheer, barfi, jelabi, rosogolla, and ras malai. Some Bengali sweets are dipped or soaked in kewra water to imbue a floral perfume. It is added to jams and conserves and sometimes sprinkled over elaborate rice dishes prepared for festive occasions. See india.

Other Flower Waters

In Thailand flowers such as jasmine are picked at sunset when their fragrance is at its best and then steeped in cooled, previously boiled water overnight. This infused water is a traditional way of serving drinking water in Thailand, as well as an important ingredient in Thai desserts and sweets.

In Tunisia rose geranium flower water is popular in drinks, confections, pastries, and mhalbiya, a cake made with rice and nuts.

Ylang-ylang is added to ice cream in Madagascar, and in South East Asia it is used in sweets and soft drinks.

See also baklava; barfi; extracts and flavorings; lokum; middle east; rosogolla; and turkey.

fondant (from the French for “melting”) is an opaque, creamy white sugar-based mixture that can be used variously as a confection (usually flavored); as a filling for chocolates; or as a coating for cake or pastry. Once refined sugar became more widely available, confectioners began to experiment with its use in candies and icings, among which was fondant. See icing. Changing the granular texture of sugar into a creamy substance is accomplished through a process of boiling the sugar with water and a small amount of glucose or corn syrup to 243°F (117°C) (the “soft-ball” stage) for a medium-firm texture. See corn syrup and glucose.

For poured fondant, the hot syrup is poured onto a smooth surface such as marble and agitated after being first briefly cooled. Working the syrup in this way leads to an opaque and creamy mixture in which the particles of sugar are so small that they are imperceptible on the tongue. The fondant is then ready to be used, after being flavored as desired with mint, other flavorings, or small quantities of spirits or liqueurs.

Firm rolled fondant, also known as sugar paste, is often used to decorate wedding cakes. See wedding cake. It is made by combining confectioner’s sugar, corn syrup, glycerine, and gelatin into a mixture firm enough to roll into thin sheets, which are then draped over the cake. This type of fondant is flexible enough to create decorative effects such as bows, flowers, and other ornamental flourishes. Buttercream icing usually coats the cake to act as an adhesive for the rolled fondant. See cake decorating.

See also gelatin; stages of sugar syrup; and sugar.

food colorings have a long and somewhat problematic history. Written evidence for their use can be found as early as 1500 b.c.e. in Egypt and Europe. Color is such a strong gastronomical cue to flavor and freshness that there are strong incentives for its use not only as an embellishment but also as an adulterant. As a result, food colorings are highly regulated, and only a handful of compounds are approved for use. Colorings derived from natural sources that have a long history of use in food are generally regarded as innocuous, although naturally derived food colorings are not necessarily safe. For example, into the twentieth century, bluestone—copper sulfate—was used in pickle recipes to give the pickles a vivid green color. Unfortunately, like many natural mineral-based colorings, copper sulfate is toxic, albeit only mildly so.

The color of a substance depends on the interaction between the material and light. Light can either interact intimately with the molecules that make up a substance or can be physically scattered off of the structure of the material itself. Food colorings, whether naturally occurring or synthetic, contain a chromophore, a structural motif within a molecule that interacts with a specific wavelength of light in the visible spectrum. The molecule absorbs this light, so the remaining light reflected back to the eye no longer appears white. Chromophores that absorb green light, for example, reflect back red light.

Common chromophores found in food colorings range from the structurally simple azo and carotenoid motifs to complex ring structures and protein–pigment complexes. Most of these chromophores can be found in both naturally occurring colorants and synthetic colors. There are no natural sources of azo dyes known, and the protein–pigment complexes have not been synthesized. In addition to their chromophores, good colorings must be chemically stable, able to maintain their color while stored for long periods and during food preparation. This presents a challenge, as the structures, and therefore the colors, of many compounds are sensitive to changes in pH and temperature.

The synthetic azo dyes are also called coal tar dyes, not because they contain coal tar, but because they were first synthesized using chemicals distilled from the black, sticky residue that remained when coal was processed. Though they are no longer produced from coal tar distillates and can be synthesized from plant sources, the name has stuck. The azo colors approved for food in the United States or the European Union include Allura Red, Sunset Yellow, and azorubine.

Natural food-safe colorings are derived from a wide range of sources, including plants, insects, and bacteria. Natural colorings can be a single chemical compound, like beta-carotene, or a complex mix of pigments and uncolored compounds, as in caramel. Orange annatto powder is extracted from the seeds of the tropical achiote shrub; the color primarily results from bixin, which has a carotenoid chromophore. Paprika, turmeric, and saffron also contain a variety of carotenoid pigments. Salmon pink canthaxanthin (which gives flamingos their characteristic hue) and beta-carotene are also natural carotenoid colors. Although both these colorants can be extracted from natural sources, in practice canthaxanthin and beta-carotene are industrially synthesized.

Brown caramel color, produced by burning a mixture of sugars under controlled conditions, is a mixture of many different molecules with carbon skeletons. Natural sources of red colors include beet red—its color due to betanin, a molecule with an anthroquinone chromophore similar to that in D&C Green 5—and cochineal, a deep red powder made from crushed dried insects. Pure carminic acid, the anthroquinone pigment responsible for cochineal’s red color, can be chemically extracted from the insects, or bacteria modified to produce it. Spirulina extract is an approved natural source for blue and green color. It is obtained from spiral-shaped bacteria that live symbiotically on tropical pond algae. The characteristic blue-green color of the dried extract derives from chlorophylls and phycocyanin protein–pigment complexes.

The playful nature of many confections encourages the use of color, and sugar is a particularly attractive base for a wide range of hues. See sugar sculpture. The reflectance of the fine-grained solid produces a pure white, whereas large crystals can be clear as glass. Aqueous solutions of sugar are transparent and nearly colorless, and so will not distort or muddy colorings. Colors in food can also be created through purely physical processes. The opaque bright white of meringues is a result of light being scattered through a dispersion of two transparent materials—egg whites and air—with very different indices of refraction. Polar bears’ fur is white for similar reasons.

See also adulteration and vision.

fools have been a popular British dessert for many centuries. Nowadays they are usually a simple mixture of mashed or puréed fruit (raw or cooked, as appropriate), mixed with custard or whipped cream, although crème fraîche or yogurt are sometimes substituted. Fools are particularly suited to northern fruits such as gooseberries, raspberries, rhubarb, and damsons, but apples, blackberries, peaches, or more exotic fruits such as mango can also be used.

The name fool may be derived from the French fouler, meaning “to press” or “to crush.” However, many early recipes in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries contained no fruit and were merely a kind of custard made of cream, eggs, and sugar, often flavored with spices, rosewater, or orange flower water. See flower waters. A likely explanation of the name is that fools, like trifles and whim-whams, are light and frivolous, mere trifles. In the early days, the words “fool” and “trifle” were frequently used interchangeably.

An early fool without fruit was Norfolk fool, popular in the seventeenth century. Custard was poured over a thinly sliced manchet (fine wheat bread) and decorated with sliced dates, sugar, and biskets (biscuits). Westminster fool also had bread as a base. The bread was soaked in sack (sweet wine) and covered with a rich, sweet custard flavored with rosewater, mace, and nutmeg.

Gooseberry fool, which became popular in Victorian times, was already known in the seventeenth century. Orange fool became a famous specialty of Boodle’s Club in London, renowned for its cuisine. The club, founded in 1762, included famous members such as the dandy Beau Brummell and more recently David Niven and Ian Fleming. Boodle’s fool has a base of sponge cake. Its creamy orange fool mixture, laced with orange liqueur, soaks into the cake to create a luscious, frothy dessert.

See also cream; custard; pudding; and trifle.

fortified wine differs from other sweet wines in that brandy (distilled grape spirit) is added to it, which yields a much higher alcoholic content. The additional alcohol is generally used to halt the fermentation abruptly before the yeast has converted all the grape sugar into alcohol (and various fermentation byproducts). Although the history of distillation goes back further, from about 1300 c.e., brandy was plentiful enough in Europe that small amounts were frequently added to various dry wines to make them more resistant to spoilage during transport. However, it was several centuries before someone added brandy directly to a fermenting wine for the first time, probably by accident, to produce a frankly sweet wine.

Madeira

The extra stability was particularly useful for the wine industry of the Portuguese island of Madeira off the northwestern coast of Africa, because Madeira’s main markets were on the other side of the Atlantic, in the Caribbean and North American colonies. Madeira’s early wines, already documented in 1450, only 31 years after the island’s discovery, resembled Malvasia Candida, a sweet straw wine from Crete. Over the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, wine production on Madeira grew dramatically. In the eighteenth century the increasing affluence, sophistication, and one-upmanship of American planters and merchants resulted in the importation of ever-finer Madeiras, leading to the development of the many styles we know today: dry Sercial, medium-dry Verdelho, sweet Bual (typically with 4 to 5 percent unfermented sweetness) and sweet Malmsey/Malvasia (typically with 5 to 10 percent unfermented sweetness), each named after the grape variety used. They are offered either as colheita (vintage) wines from a single year (declared on the label), or as blended multi-vintage wines of a minimum age (e.g., Reserve, which is aged 5 years; Special Reserve, aged 10 years). Bual has a rich, raisin flavor, while the lusher Malmsey offers a more pronounced interplay of acidity and sweetness. Vintage wines of both types can age for a century or more. Rainwater, mainly exported to North America, is a lighter style of slightly sweet Madeira made primarily from the Tinta Negra Mole grape.

Although Madeira’s maritime climate, with a tropical influence and its terraced vineyards ascending to almost 2,750 feet above the Atlantic Ocean, creates special winegrowing conditions, the wines are more strongly marked by a unique aspect of the winemaking process. Estufagem imitates what wines shipped in barrels through the tropics would have undergone and gives Madeira wines their peculiar caramel-like flavor. It also hastens the oxidation that leads to the deep amber color with a distinctive green tinge at the rim of the glass. In the crudest form of this process (cuba de calor), the wine is directly heated to about 120°F (49°C) for three months, but today the majority of Madeiras exported are heated by the casks being placed in a sauna-like cellar (armazém de calor), and sometimes the finest wines are not heated artificially at all (canteiro). Estufagem was introduced during the eighteenth century, before the British influence on Madeira became stronger after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1814, which means that Madeira is actually a Portuguese-American wine, rather than a British one, as is often claimed.

Port

Fortification also appears to have come to the Douro Valley of Portugal during the first half of the eighteenth century. By 1800 the new sweet red port wines, typically with an alcohol content of 18 to 20 percent and 8 to10 percent grape sweetness, gradually replaced the region’s previous style of more-or-less dry, full-bodied red in the main export market to England. Most of the region’s wines then were like today’s tawny ports—sweet, fortified port wines matured for between a few years and several decades in cellars located in the Oporto suburb of Villa Nova de Gaia, the home of the main port houses.

“Tawny” refers to the amber-brown color these red wines acquire through this aging process. The characteristic aromas are reminiscent of toffee, candied citrus peel, and roasted nuts. Today the finest ports of this kind are marketed either as single vintage colheita or as multi-vintage blends with declared minimum age (e.g., 10 Years Old, 20 Years Old). The older they are, the less grape tannin they contain and the more supple they taste, until, after about 30 years of aging, concentration through evaporation from the barrel increases the acidity content significantly. Unlike the single-variety wines of Madeira, port is always a blend of a handful or more indigenous grape varieties, most important Touriga Nacional and Tinta Roriz (known in Spain and many other countries as Tempranillo). Traditionally these grapes are fermented in shallow granite troughs called lagares, where they are foot-trodden to extract the maximum amount of color, tannin and aroma from the grape skins before grape spirit is added to arrest the fermentation. Today much of this treading is done mechanically.

Only during the early nineteenth century did the practice develop of bottling some ports after just a couple of years of cask maturation when they are still deep in color and full of fruit aromas and grape tannin. This is how vintage port tastes when released, as well as the lighter and less tannic late bottled vintage (LBV) port and the even simpler ruby port. All of these styles were at least indirectly the product of British influence on the region, dating back to the 1703 Methuen Treaty between Britain and Portugal. No other European wine has a more British image than Vintage port, which traditionalists in Britain did not consume before it had had 20 years of aging to soften the wines’ often enormous tannins. Today, in England no less than in the important U.S. market, most vintage port is drunk much younger than that.

Sherry

Sweet sherry from the region around Jerez in Spain is a special case among sweet fortified wines, since the sweetness of a Cream sherry results from the blending of a fortified straw wine called PX (after the Pedro Ximénez grape from which it is exclusively made) with a fortified bone-dry Oloroso. The latter has been aged in a solera, a collection of casks to which younger wines are added so that they acquire character from the older wines it contains, yielding a wine with a consistent mature flavor. This blend yields a dark-amber to pale-brown wine with a rich, nutty, and dried fig or date character, with at least 15.5 percent alcohol and over 11.5 percent unfermented grape sweetness. Pure PX is mahogany brown with an enormously intense raisin aroma and flavor, and at least 21.2 percent grape sweetness. It is sometimes aged in cask for decades as a rare and unctuous specialty.

Other Fortified Wines

By the late nineteenth century, the wine industries of South Africa and Australia were producing modestly priced port- and sherry-style sweet wines on an industrial scale primarily to supply the British market. After World War II, when Britain’s consumption of sherry declined significantly, they switched increasingly to dry table wine production. Only Rutherglen in Victoria, Australia, managed to build such a reputation for Tawny port (usually from the Shiraz, Mataro, and Grenache grapes) and similar sweet fortified wines from the Muscat grape that it defied this change in fashion. These wines can match the best Portuguese tawny ports, but they tend to be even lusher.

In recent years, with the resurgence of port’s popularity, wines in this style have been produced in small quantities in an astonishing range of other wine-growing zones from California to Germany, and from all manner of grape varieties. None of these imitators can match Banyuls, though, the port-like fortified wine produced both as a vintage wine (resembling vintage port) and a blended nonvintage product (resembling tawny port) from the part of French Catalonia closest to the Spanish border. The greatest differences between these wines and port are their lower alcoholic content, typically about 16 percent, and the use mainly of Grenache grapes.

A footnote to the category of fortified wines includes wines made where there are no clear legal requirements, such as Commandaria from Cyprus. This straw wine made from the indigenous Mavro and Xynisteri grapes typically has full body comparable to a ruby port and a raisin character like PX.

See also fermentation and sweet wine.

fortune cookie is a folded, crescent-shaped wafer with a piece of paper tucked inside, most commonly distributed by Chinese restaurants in the United States. Over 3 billion are made each year.

Although the vanilla-flavored fortune cookie—with its distinctive shape and pithy sayings—has become an icon of Chinese culture in America, it most likely traces its roots to Japan, as the cookies are all but unknown in China. Similar crescent-shaped confectionery treats, known variously as tsujiura senbei (“fortune crackers”) or suzu senbei (“bell crackers”), flavored with miso and sesame, are still sold by bakers in the former capital city of Kyoto. See kyoto. The senbei are heated over fire with iron grills called kata and folded by hand, in contrast to the highly automated processes that produce American fortune cookies. Japanese immigrants brought the treat to California around the turn of the twentieth century. One of the earliest popular venues for the cookies was at the Japanese Tea Garden in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park.

By the end of World War II, fortune cookie production was largely taken over by Chinese immigrants, in part because of Japanese internment during the war. The cookies exploded in popularity in the postwar era, spreading eastward from California, to the point that they were used in a number of political campaigns in the 1960s and became an American staple by the 1980s. In addition to the original pithy and prophetic sayings, fortune cookie slips sometimes include “lucky numbers,” which many Americans now use to play the lotteries.

Although fortune cookies are universal at American Chinese restaurants, they are virtually unknown in China. These crisp, folded wafers were developed by Japanese immigrants to the United States at the turn of the twentieth century. © flazingo photos, www.flazingo.com

Today, there are fruit-flavored fortune cookies, giant fortune cookies, chocolate-dipped fortune cookies, dog fortune cookies, X-rated fortune cookie messages, and even Mexican fortune cookies shaped like tacos. Fortune cookies are also made in Brazil, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom.

Fourier, Charles (1772–1837), the utopian thinker often referred to as one of the earliest socialist theoreticians, is best known for the extraordinary level of detail in his elaborate—and often eccentric—vision of the future. Seventeen years old when the French Revolution erupted, his world turned upside down and his fortune lost, he retained a lasting hatred for what he disparagingly called “civilisation,” including its sharp commercial practices (particularly those designed to manipulate commodity prices), toleration of poverty, and republicanism—especially its “Spartan” attitudes toward diet.

In Fourier’s new society, called Harmony, everyone would live as they wished, recognizing their own tastes in work and in leisure and realizing these preferences in the company of like-minded people. In agrarian communities called phalanxes or phalansteries, one person of each gender and each temperament (a total of 1,620) would live together in beautiful buildings surrounded by fertile countryside, undertaking pleasurable work in short bursts, alternated with even more pleasurable leisure, all interspersed with up to nine delicious meals and snacks a day. No one would ever have to eat anything they did not like (such as turnips or cabbages, pet hates of Fourier’s). Sex and food were to be recognized as the most important elements in this good life, taking their places together at the pinnacle of Harmonic religion. Fourier believed these were the essential human joys, especially food—and, in particular, sweet food—which, he pointed out, was the very first happiness of a child and the last one remaining to the elderly adult who had aged beyond the pleasures of the flesh.

The education of children would begin in the kitchen, and everyone would learn the science of “gastrosophy”: a combination of learning to grow food, cook it, and match it to the temperament, health, and preferences of each individual. Sugar would play its part in international diplomacy. War would be replaced with giant worldwide gastronomic contests focused on the making of fine pastries, especially Fourier’s favourite, the mirliton, a puff-pastry tartlet with an airy baked filling of beaten eggs and sugar enriched with crushed macarons and candied orange blossoms, pistachios, or other flavorings. As a result of beneficial climate change, crops—especially sweet fruits like Muscat melons and bergamot pears—would be plentiful and of a quality unimaginable in today’s conditions. Most important, sugar would be cheaper than wheat. Thus, the bread of Harmony would be fruit compote: fruit cooked with a quarter of its weight in sugar, a food with multiple benefits demonstrating many of Fourier’s core theories of economic efficiency and pleasure. First, fruit, and sugar would be cheap and plentiful, making this Harmonic bread an eighth of the price of “civilized” bread and equally accessible to rich and poor. Second, compote cuts down on wasted time and wasted food, as it can be made in advance and more quickly than bread, and it keeps better. Third, everyone prefers sweet food, especially women and children who, Fourier says, have a notoriously sweet tooth—rather like Fourier himself. Any concerns about the pernicious influence of too much sugar would be addressed by the ready supply of “balancing” acidic drinks such as lemonades and wines (and replaceable teeth). For sugar enthusiasts like Fourier, such a sweet life could be utopia indeed.

France became one of the first countries to explore the possibilities of sugar when cheap supplies came flooding in from the Caribbean and South America at the start of the seventeenth century. French patissiers became the acknowledged masters of the art of cooking with sugar, taking over from the Italians. Le pastissier françois, published in Paris in 1653, was the first European cookbook devoted to pastry, clearly written by a pastry cook though the author is unknown. By midcentury a whole table at a banquet might be devoted to sweets, which also developed as a separate course to end the meal. The word “dessert” itself is derived from the French desservir, meaning to “clear the table of dishes” from the previous course. See dessert. It was in France that sugar specialties first emerged from the more day-to-day work of the patissier: glaces (sorbets and ice cream), confiserie (candies and petits fours), and travail au sucre (sugar sculpting), with a subspecialty in chocolaterie (chocolate work). Boulangers (bakers) had long plied their métier independently, baking in the four banal (communal oven) the wheaten loaves that were the staple food of the nation.

Following this lead over the centuries, a distinguished line of French pastry cooks developed. In 1751 Le cannameliste français appeared, a definitive guide to sugar work by Joseph Gilliers, head of the cold kitchen for Stanislaus, duke of Lorraine. See gilliers, joseph. Early in the nineteenth century Marie-Antoine Carême created staggering architectural fantasies in sugar that he describes in Le pâtissier pittoresque (1815). See carême, marie-antoine and sugar sculpture. That same year he cooked for the French Prince Talleyrand (a gourmet of renown) at the Congress of Vienna, as well as Tsar Alexander I when he visited France, before moving on to become chef to the British prince regent. Other important names include William Jarrin and Alphonse Gouffé, pastry chef to Queen Victoria. See jarrin, william alexis. Today, French patisserie is global, led by pastry chefs such as the Lenôtre family, Pierre Hermé, and the Ladurée group, famous for their macarons. See hermé, pierre; lenôtre, gaston; and macarons.

Already in Le pastissier françois, the structure of classic French patisserie can be seen; here are the gâteaux and cakes, the genoises and biscuits, with the crème pâtissière (pastry cream) and crème au beurre (buttercream) to fill them. Pastries include choux and puff, immediately recognizable as the recipes we use today. Most obvious to any visitor to France are the classic French gâteaux, sometimes baked at home but most often bought in the patisserie for Sunday lunch or a birthday. Most popular is génoise, a simple sponge of whole eggs, sugar, and flour, sometimes butter too, cooked in a characteristic moule à manqué with sloping sides. See cake and sponge cake. Character is added to génoise with fillings of pastry or buttercream, with perhaps a sprinkling of rum or kirsch syrup on the cake itself. Favorite flavorings include coffee (gâteau moka), chocolate, orange (gâteau Grand Marnier), and berries such as raspberry and strawberry.

France has been known for the skill of its patissiers, or pastry chefs, since the seventeenth century. This etching by Abraham Bosse, titled Pastry Shop, depicts the activities that take place within, from rolling out dough to shaping and baking it. The verses explain that “This shop has delicacies / That charm in a thousand ways / Girls and little boys / Servants and wet nurses.”metropolitan museum of art, harris brisbane dick fund, 1926.