race is connected to sweets in many and various ways. Central to any discussion of the relation between the two is power and the ways in which it informs our historical and contemporary understanding of sweetness. In many cultures, sweets have had a history as commodities of racism, or as objects used to distribute racist imagery, messages, and logic. Several racial or ethnic groups have been linked with negative connotations involving certain sweets (Haribo black licorice, for example). Focused on here is the African American experience in the United States, and the associated stereotypes, racist depictions, and health issues related to this experience.

Production

Two commodities—sugar and slaves—were significant to the growth of transatlantic commerce, and the production of sugar is directly tied to the enslavement and exploitation of Arawaks, Africans, and African Americans whose labor helped the Atlantic economy to burgeon. From the sugar plantations of the Caribbean to those of the American South, enslaved peoples worked the sugarcane fields and plantations and were essential to the Triangle trade. See plantations, sugar and sugar trade. Across the ocean, for a long while, Pacific Islanders were the source of cheap labor in the sugarcane fields of Australia. Whether in the East or the West, the campaign for sugar functioned to enhance the lives of some while degrading the lives of many others. Due to sugar’s status as a luxury item, it sold for high prices, making investment in its production and trade profitable, especially for European merchants. For the enslaved in the United States and the Caribbean, sugar production was especially arduous work, with seasonal rotations and long hours for those who worked in labor gangs. The paltry rations given sugarcane workers further reduced their life expectancy. See slavery.

As agents of reproduction, women were especially affected by the back-breaking toil of sugarcane production. In addition to working long hours, women generally had the responsibility for feeding their families. It is not well known that the antebellum food-service industry provided some opportunities for black women to participate in the early American economy. While free black men primarily dominated the catering industry, some enslaved, but mostly freed, African American women, like the higglers of the British Caribbean and quitandeiras of Brazil, sold foods and beverages as hucksters and hawkers. Success from these modest ventures was often measured by the ability to secure one’s freedom or augment family earnings. By capitalizing on menial occupations, these early entrepreneurs profited from the sugar and molasses that figured in the sweetening of many beverages and ice cream, cakes, pastries, fritters, pralines, calas (rice cakes), and other baked goods. See new orleans and praline. Even after the Civil War, African American women are said to have passed on the art of making fudge, taffy, pecan caramels, and all sorts of brittles to their children.

Stereotypes and Racist Depictions

While African Americans continued to experience some economic advancement in the food industry, Reconstruction ushered in new, racist ideologies that were expressed in popular and material culture. From the 1880s to the 1930s, black people were portrayed in almost universally derogatory ways as very dark, nappy-headed, bulging-eyed, childlike, and overly deferential. And they were almost always depicted as happy, with an uncontrollable appetite for watermelons.

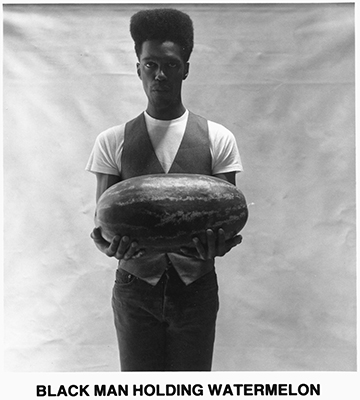

Carrie Mae Weems’s series Ain’t Jokin (1987–1988) explores racist stereotypes by pairing mundane but culturally loaded objects with acerbic commentary. Black Man Holding Watermelon asks why African Americans are so closely associated with the fruit; those familiar with that stereotype might ask, What is wrong with this picture? © carrie mae weems. courtesy of the artist and jack shainman gallery, new york

From minstrel shows to sheet music, postcards to photographs and films, African Americans were caricatured as stealing, eating, and even becoming watermelons. The meanings of this association are many, but the imagery was mainly intended to depict African Americans as simple-minded, content to laze around and happily eat watermelon. The early twentieth century, for example, witnessed white functions and events where blacks provided the entertainment by engaging in watermelon-eating contests. A 1937 cover of Life magazine helped to perpetuate these stereotypes by depicting a wagon full of watermelons with an African American man, his back bared, sitting on the edge of a cart looking out toward a dirt road, with farmland on either side. Another image accompanying the story was captioned “The watermelon starts its journey to market in an ordinary wheelbarrow pushed by a grinning Negro.”

In her installation Ain’t Jokin, the visual artist Carrie Mae Weems (b. 1953) emphasizes the cultural potency of race and mundane objects of material culture like sweets. One of the images, Black Man Holding Watermelon, forces viewers to ask why African Americans are associated with the fruit; those familiar with the stereotype might ask, what is wrong with this picture? Using watermelon and other sweets, artists such as Weems highlight how such foods remain culturally explosive. In 2008 this stereotype boldly emerged when, during and immediately after the successful presidential bid of Barack Obama, images began circulating that showed watermelons on the White House lawn, one bearing the caption “No Easter egg hunt this year”—evidence not only of the pervasiveness of this particular sweet, but also of the enduring legacy of racial associations that it continues to invoke.

More recently, controversy erupted on the Internet when the opinion columnist Theodore Johnson pointed out that the familiar jingle “Turkey in the Straw” blaring from many ice cream trucks could be associated with the “coon songs” of the past. Though the actual song has a long history that predates its arrival in America, lyrics that originated in blackface minstrelsy were sometimes added to the melody. The words of one song in particular—“Nigger Love a Watermelon Ha! Ha! Ha!,” written by Harry C. Browne in 1916—make reference to watermelon as the “colored man’s ice cream.” Johnson notes that the impact of racism is enduring, especially when it is hidden in “the nooks and crannies of wholesome Americana.”

Health Disparities

The relation between African Americans and watermelon is not wholly unfounded, although it is greatly exaggerated. Watermelon is, in general, a familiar fruit in Southern foodways. However, African American dietary habits, choices, and cooking methods, though largely Southern in derivation, have evolved from a long history of slavery, oppression, and segregation, resulting in decidedly different health outcomes today. See south (u.s.).

Though health disparities exist among all racial and ethnic groups across socioeconomic strata, it has been argued widely that there is a higher prevalence of obesity and weight-related diseases—cardiovascular problems and diabetes, for example—among African Americans. According to some studies, the reasons for these disproportions are not well understood. Others maintain that rather than the foods themselves, it is the long-held cultural beliefs, behaviors, and attitudes informing cooking methods—including the excessive use of sweeteners and fats—that have contributed to these health concerns. See sugar and health. At least one study suggests that among today’s African American youth and children, when compared to European Americans, there is an elevated preference for sweet tastes that begins in childhood. The same study found that, beyond young adulthood, African Americans may derive comfort and sustained pleasure from the repeated intake of sweet tastes in order to alleviate stresses stemming from racial inequalities.

Ironically, in 2014, the African American visual artist Kara Walker paid homage to the “unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World” by creating a sphinx-like, 75-foot sculpture of white sugar and carved polystyrene. The figure, titled A Subtlety: The Marvelous Sugar Baby, bears a likeness to countless caricatures of African American women—heavyset, thick-lipped, wide-nosed, and kerchief wearing. In this sculpture, Walker not only encapsulates vestiges of entrepreneurship, stereotyping, and health, but like Carrie Mae Weems, she draws attention to the destabilizing tensions of representation, race, and power that most likely will forever link African Americans to white sugar sweetness. See art.

Ramadan is the holiest month in the Muslim lunar calendar, during which the consumption of sweets reaches dizzying heights. After abstaining from food and drink from sunrise to sunset, fasters gratify their deprived appetites with a varied meal known as iftar, followed by some ultra-sweet desserts. Such indulgences might have been largely encouraged by a widely circulated, albeit questionable, oral tradition of the Prophet Muhammad that describes true believers as lovers of sweets. Another tradition says that true believers love dates. See dates and islam. Indeed, Muslims worldwide traditionally break their daylong fast with a few dates, following the Prophet’s example, along with some water or yogurt. It should be noted that modern medicine has given its nod of approval to this sweet ritual: while the body rapidly gets the nourishment it needs, the dairy slows down elevated sugar levels.

The sugary Ramadan lavishness may historically be traced back to medieval times, when sugarcane cultivation became widespread in the Middle East with the rapid expansion of the ruling Muslim empires. See sugarcane and sugarcane agriculture. We have ample evidence of the dizzying arrays of confections, including sculpted ones, made in the kitchens of the elite and at the specialized sweets-markets. But in relation to Ramadan accounts of customs and practices, the Egyptian Fatimid era from the tenth to the twelfth centuries offers the most detail, as related in Nasir Khusraw’s Safarnama and al-Maqrizi’s Khuṭaṭ.

For the Fatimids, dessert was a celebratory food, and they took great pains to impress with it. In the royal kitchens, hundreds of dessert chefs were employed and immense quantities of ingredients were used to prepare the enormous platters distributed to high and low, rich and poor, in celebration of Ramadan. They were loaded with stuffed cookies like khushkananaj and basandūd; shelled nuts, raisins, and dates; and the ring-shaped hard sugar-candy sukkar Sulaymāni. Also included were the sweet digestives juwarishnat, natif (nougat), and fanīdh (pulled taffy). See nougat and taffy. Cooks began preparations for these gift trays 10 weeks ahead of time. During the Ramadan iftar meal, colored hard candies (halwa yabisa) outlined the table, and bowls of condensed puddings were abundantly arranged across it. See hard candy. Servers would begin arranging the banquet table at midnight. A citrus tree, complete with branches, leaves, and fruit, all made of sugar, served as a fabulous centerpiece. Underneath were arranged almost one thousand sugar statuettes. To celebrate the end of Ramadan, two huge sculpted sugar palaces were placed at both ends of the dining table. See sugar sculpture.

Sweet celebrations continued to be important in Ramadan during the time of the Ottomans. Puddings, thick starch-based halva, syrupy pastries, jams and electuaries, toffees, nougats, and many other desserts comparable to those served in Egypt appeared on the table, along with a host of other sweets either adapted or invented. Baklava loomed large. See baklava. The most famous Ramadan tradition goes back to the end of the sixteenth century, when the Baklava Procession was first held annually on the fifteenth day of the month. Hundreds of trays of baklava for the janissaries were baked in the palace kitchens. Tied in cloths to keep the sticky pastries clean of dust, these trays were carried to the barracks in pomp.

Today, Muslims typically first wash down the iftar meal with fruits or light milk muhallabiyya puddings thickened with cornstarch or rice flour. The Iranian variation called zerde is tinted yellow with saffron, while the Indian kheer uses vermicelli noodles for a starch. See india and persia. Dried fruit compote (khoshaf) is popular in Egypt and Turkey. Its Indonesian counterpart kolek/kolak is made with coconut milk, palm sugar, pandan leaves, and fresh and dried fruits. It is not unusual for sweets to be consumed even within the course of the meal itself. In Morocco, for instance, the spicy harira soup is eaten together with shabbakiyya, flower-shaped cookies fried and drenched in honey.

After some rest, people go out to socialize and enjoy desserts with tea or coffee, or they patronize all-night dessert shops where popular Ramadan confections are offered. These are mostly sticky, rich, fried treats, often filled with nuts or sweet cheese or clotted cream and drenched in syrup. Qatayif (Arabian pancakes), kunafa (vermicelli-like pastry), and baklava are ubiquitous in the Middle East. See qaṭā’if. Even more widespread is the latticed zalabiya, called mushabbak in the Levant, zulbia in Iran, and jalebi on the Indian subcontinent and in Afghanistan. See zalabiya. Semolina is found in such Ramadan favorites as the moist semolina cakes variously known as basbousa in Egypt, nammora in Lebanon, hareesa in Syria, and qalb el-louz in Algeria; in Afghanistan and on the Indian subcontinent, semolina is cooked into a dense pudding called suji halwa. See halvah. A Ramadan sweet indigenous to Southeast Asia and southern China is kuih (and other linguistic variants), made in many different ways, the most common of which is the Indonesian layered multicolored steamed cake kue lapis. It consists of steamed thin layers of batter made with flours of tapioca, rice, and mung beans, mixed with sugar syrup, coconut milk, and pandan leaves. All these sweets are available year round, but they are most frequently consumed during Ramadan.

In Iraq and other Gulf countries, the children receive their own share of Ramadan sweet delights by going door to door singing and asking for sweets. This practice, called Qarqīʿān or Majīna, takes place in the middle days of Ramadan and is believed to date back to the birth of the Prophet’s grandson Hasan ibn Ali on the fifteenth of this month. The children of Medina, the story goes, gathered around the prophet’s house singing Qarrat al-ʿain (Congratulations), and the Prophet rewarded them with sweets, dates and raisins.

See also china; dessert; dried fruit; fried dough; middle east; south asia; southeast asia; and turkey.

Reese’s Pieces, Hershey’s popular candy shells filled with a peanut butter mixture, would never have become famous without the help of competitor M&M’s.

The fact that M&M’s had been America’s best-selling candy since its introduction in the early 1940s infuriated Hershey executives, especially because Milton Hershey’s right-hand man William Murrie had helped Forrest E. Mars Sr. launch the M&M brand. Hershey’s had supplied M&M’s with chocolate and helped the business throughout World War II when rationing made supplies scarce. Murrie’s son Bruce went into business with Forrest Mars, representing the second M on M&M’s, but Forrest forced Bruce out when he had no further use for his Hershey connections. See hershey’s; mars; and m&m’s.

In 1954 Hershey’s went head-to-head against M&M’s with its own product, called Hershey-ets. But Hershey-ets proved difficult to sell because it was nearly impossible to describe them without invoking the competition’s name—the products were simply too similar. Hershey abandoned Hershey-ets in the 1970s. But the leftover Hershey-ets candy-making equipment gave marketers an idea. Instead of making a product exactly like M&M’s, Hershey’s could make a candy more like its best-selling Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup. However, creating a peanut-butter center that did not leak peanut oil was not easy. Hershey’s turned the job over to an outside food-science firm that developed a special paste dubbed “penuche”—a blend of peanuts and sugar that contained very little peanut oil, so the filling would not spoil or soften the candy coating over time.

To avoid comparison with M&M’s, Hershey executives decided that the new product would not contain chocolate. The candies were brown and orange, reflecting the Reese’s brand, and the name Reese’s Pieces was born. The candies were introduced nationally in 1980, and Hershey had high hopes for the brand. But after a promising start, sales began to fall, putting Hershey’s multimillion-dollar investment in jeopardy.

In October 1981 Universal Pictures approached Mars, Inc. about using its M&M’s product in an upcoming movie about an alien stranded on Earth who befriends a little boy. The boy would use the M&M’s to lure the tiny alien out of his backyard and into his home. But the executives at Mars refused, fearing that any association with an alien creature could send the wrong message about its product. So Universal turned to Hershey’s. They offered Reese’s Pieces a shot at the movie, telling Hershey executives the movie would boost candy sales and, in return, the candy could promote the movie. Hershey executives signed an agreement pledging $1 million worth of candy promotions for E.T. in exchange for the opportunity. A step beyond traditional product placement whereby a consumer product appears in a show or film, this was one of the first cases of “brand integration,” in which a brand features prominently in the actual plot.

When E.T. opened, it immediately began breaking box office records around the world, and sales of Reese’s Pieces skyrocketed. The Reese’s Pieces brand has remained popular with consumers ever since, although sales dipped again shortly after the movie hype died down. Nevertheless, the idea of candy-coated pieces remains a Hershey staple, and today the company sells many Pieces varieties, including Almond Joy, Peppermint Patties, Hershey’s Special Dark, and Hershey’s Milk Chocolate with Almonds. No doubt if Mars had accepted the Universal offer, none of these candies would exist today.

See also hershey, milton s.

refrigeration is the chilling of a food or a liquid from the ambient temperature to a lower one by removing heat through convection or conduction. Refrigeration enables liquids and foods to last longer because the microorganisms naturally occurring in them (bacteria, yeasts, and molds) multiply most readily in a temperature range of 77°F (25°C) to 86°F (30°C). Reducing the ambient temperature in and around the food by refrigeration significantly slows down the ability of the microorganisms to multiply, thereby reducing the likelihood that the food will spoil.

The earliest form of refrigeration was achieved simply by surrounding the food or liquid with ice or snow in order to reduce the temperature. Consuming chilled food was a novelty, and the sensation was greatly enjoyed. Affluent families farmed ice from rivers and lakes on their estates to store in specially constructed icehouses designed to keep the ice from melting for as long as possible. They were usually sited under trees or on the shady side of a building, often partially or completely below ground. The ice, insulated with wood and straw, could be kept year round for making ice creams and other chilled desserts. See desserts, chilled; desserts, frozen; and ice cream. In harsher climates, cold temperatures were easier to maintain; Russian noblemen, for instance, had vast, naturally cooled cellars that were perfect for aging mead. See mead and russia.

Freezing preserves liquids and foods for months, and in some cases for years. Freezing cools a chilled food or liquid to below its freezing point, where it solidifies. This point varies according to water content. The higher the water content of a food, the more solid it will be at the freezing point of water. Freezing a liquid requires more science than mere refrigeration. The addition of various salts (e.g., sodium chloride, or table salt) to ice reduces the temperature of the ice. It is possible to reduce the temperature of ice to about 6°F (−21°C) by adding salt, a practice historically used in the production of sorbets and ices. See italian ice and sherbet. Today, rock salt is added to ice to more effectively freeze the custard when making ice cream in hand-cranked machines. A temperature of −3°F (−16°C) can easily be achieved at home by this method. See ice cream makers.

When and where this endothermic effect of salt on ice was discovered is unknown. The historian Joseph Needham, in his monumental work Science and Civilisation in China, considers it unlikely that the freezing effect of salt solutions was a European discovery; he believes that it reached Europe from the East via the Arabs and Moors during their time in Spain (711–1492 c.e.). The first European record of the endothermic effect dates to 1530, when the Italian physician Marco Antonio Zimara of Padua wrote in his Problemata about the use of niter (sodium nitrate) for chilling liquids.

Commercial Ice Trade

By the nineteenth century, supplying ice for chilled and frozen confectionery, as well as for keeping perishable food from spoiling, had become big business. Wealthy people in major Western cities had iceboxes (early refrigerators), into which the local iceman delivered, on a regular basis, big blocks of ice. This business was labor and transport intensive and depended on the weather for the production of ice. In 1842 the entrepreneur Frederic Tudor began shipping ice from the United States to England, and in 1850 Carlo Gatti shipped ice from Norway to London. Other companies shipped ice from the United States to South America and even to India (Chennai’s famous icehouse stored ice shipped from the States by Frederic Tudor; it is now the Swami Vivekananda House). However, with the advent of mechanical refrigeration, this industry died out.

Mechanical Refrigeration

The first known method of mechanical refrigeration was demonstrated in 1756 by William Cullen, a surgeon and chemist at Edinburgh University. In 1842 John Gorrie designed a system to refrigerate water to produce ice, but it was a commercial failure. Six years later, Alexander Twining initiated commercial refrigeration in the United States, and by 1856 mechanical refrigeration had developed into an industry.

Though refrigerated railroad cars using a mixture of salt and ice were introduced in the United States in the 1840s, it was not until the 1860s that mechanical refrigeration came into use on the railroads. In the mid-twentieth century, refrigerated trucks became commonplace on the roads. Mechanical refrigeration meant that meat and perishable foods could be shipped, frozen, to Europe and North America from Australia, New Zealand, or Argentina, and still arrive frozen and in good condition. Professional confectioners were early adopters of this method, especially the Sara Lee Company in the United States, which revolutionized the process in the 1950s. See sara lee. The new equipment enabled bakeries to broaden their offerings with a wider selection of ice creams and cakes iced with buttercream.

Domestic mechanical refrigerators first appeared around 1914–1915. They came with small freezer boxes inside that were usually suitable only for making ice cubes for drinks. The larger refrigerator compartment, however, enabled the owner to keep milk and cold drinks, as well as milk-based desserts, blancmanges, trifles, puddings, jelled desserts, and, soon enough, icebox cakes. See blancmange; gelatin desserts; icebox cake; pudding; and trifle.

Freeze-Drying

Freeze-drying, developed during World War II, consists of freezing a substance in a vacuum in order to remove any water or ice. Used extensively for pharmaceutical products, it was adopted in the latter part of the twentieth century for culinary use, to make freeze-dried ice cream that could be stored unrefrigerated and then rehydrated to be eaten by astronauts, among others.

Freezing with Liquid Nitrogen

Freezing by means of cryogenic liquids was first mentioned in 1894 by James Dewar at a lecture at the Royal Institution in London. Astonishingly, the Victorian cook Mrs. Marshall mentioned this method in her magazine, The Table, on 24 August 1901, suggesting that it would soon be possible for guests to make their own ice cream at the table. See marshall, agnes bertha. Although the process had been familiar to food technologists for decades, it was not until 1999, when Heston Blumenthal used it to great effect in his restaurant The Fat Duck, that the technique came to the notice of the public. Blumenthal continues to experiment today, with liquid-nitrogen–chilled ice creams made of chicken puree and curry, or of frozen reindeer milk and bacon.

See buddhism; christianity; hinduism; islam; and judaism.

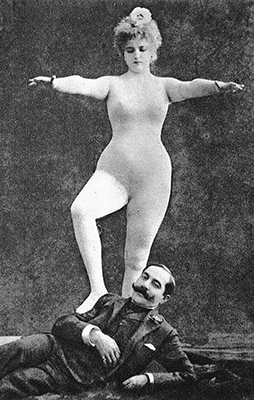

Rigó Jancsi, the Hungarian cake named for a Gypsy violinist, is literally the stuff of legend. Dazzling stories surround it, but few details of its creation are known. What is certain, however, is that this luscious torta (cake) was the result of an affair that began in 1896 Paris. Rigó and an American millionairess from Detroit, Clara Ward—by marriage the (Belgian) Princess Caraman-Chimay—met in Café Paillard, one of the grand restaurants of the boulevards. Some say on that occasion, with music the food of love, the Gypsy virtuoso played his violin to irresistible effect. Others characterize the princess as an adventuress ready to bolt. Whether one or the other is the case, or both, the two ran off together, divorced their respective spouses, and, in time, married.

Clara Ward was an American millionairess who became a princess after marrying a Belgian prince, but she left him for a Hungarian Gypsy violinist named Rigó Jancsi. Their love affair inspired a rich chocolate sponge cake that still bears the violinist’s name. In this 1905 photograph, Clara Ward poses provocatively above her lover.

To the European aristocracy into which Clara’s husband, the Prince Caraman-Chimay, was born, the scandal was profoundly shocking. To the populace, especially that of Hungary, where Johnny Rigo was the hometown boy, he and his princess were almost folk heroes. Eventually, someone—no one knows who or exactly when—created a voluptuous cake (layers of chocolate sponge filled with chocolate cream, and glazed with chocolate) inspired by the flamboyant pair. In one version of the story, it was a pastry chef; in another, it was the Gypsy who asked for a cake that would be “dark and ruggedly handsome like Rigó Jancsi himself, sweet as their love, and delicate as his wife.”

Whatever the origins of this now-classic cake—and despite the existence of numerous photographs and postcards of the couple, and even a lithograph of the two by Toulouse-Lautrec—more than a century after its creation, this edible symbol of love and lust remains the chief remembrance of Rigó Jancsi and his exploits. Still a favorite, not only in the countries of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire, but elsewhere in Europe, the United States, and Australia, it lives on as a testament to consuming passion.

rock is a traditional confection of British seaside resorts made from pulled sugar. Made in long sticks, flavored with mint or fruit essences, it has a brightly colored, often red, exterior. The white inner core mysteriously encloses letters spelling the name of the resort, or sometimes has a complex pattern—a flower, a fruit, a face—running its length.

Making rock is simple in principle. Sugar is boiled to the hard crack stage 302°F (150°C) then divided and colored, usually adding red to a small proportion and leaving the rest plain. See stages of sugar boiling. The uncolored batch is pulled until it is white, and some of it is shaped into a short, thick cone and kept warm. The colored batch is divided into strips, and the design is built up with some of the pulled colored sugar. For instance, a letter O is formed by wrapping a cylinder of white sugar in an outer coat of red. These lengths containing patterns are assembled around the cone, the whole is wrapped in pulled sugar, and a colored coat is added to the exterior. A machine spins the cone of rock into long, slender cylinders that are gently rolled until cool to keep their cylindrical form. Then they are cut into short lengths, revealing the pattern across the ends, and wrapped in cellophane along with a picture of the resort in which they are sold.

Rock has been sold as a souvenir in the United Kingdom since the late nineteenth century. The notion of putting lettering in sugar sticks was mentioned by Sir Henry Mayhew in London Labour and the London Poor in 1864, but pulling striped sugar into lengths (as seen in candy canes) is an older idea. See candy canes. The association of pulled sugar with the seaside is mysterious but may originally relate to the concept of sugar as an ingredient that counteracted cold in the Galenic system of humors. See medicinal uses of sugar. Although rock with complex patterns in the middle seems to have developed in an English context, Italian illustrations from the nineteenth century show vendors pulling sugar as a novelty sold on the beach in Naples.

See also boardwalks and hard candy.

rolled cookies are prepared from a dense dough that is rolled flat and cut into a variety of shapes. They are most popular during celebrations and holidays, when they are colorfully decorated, iced, or covered with confectioner’s sugar, glazes, fondant, colored sugars, or small candies. See fondant and holiday sweets. Sugar cookies are common, since they are a good canvas for added flavors. Ingredients such as chocolate, mint, cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger, or nuts may be added to the cookie dough; gingerbread cookies are especially popular. See gingerbread and nuts.

The dough typically contains flour, butter, sugar, eggs, and baking powder. All-purpose, or medium-protein flour, is used because it creates an elastic dough that can be rolled into a thin layer while holding its shape. Great care should be taken when mixing the dough. There are two basic ways to make dough for rolled cookies. The first, known as the creamed method, calls for creaming room-temperature fat with sugar. Then eggs or liquids, and finally the dry ingredients, are added and mixed only until the dough forms. For the one-stage method, all the ingredients are added to the bowl and mixed at slow speed for a few minutes until they are evenly incorporated. With either method, the dough should never be overmixed because that toughens it.

After the dough is made it should be covered and refrigerated for about 30 minutes before rolling, which allows the protein to relax and form a firmer mass that is easier to roll. Keeping the counter lightly dusted with flour when rolling allows the dough to glide rather than stretch. Stretching overactivates the gluten in the dough and causes the cookies to shrink and become oddly shaped.

Rolled cookies are usually baked at 300° to 325°F (148° to 163°C). These low temperatures allow the oven heat to slowly penetrate the cookies for even baking and browning. The cookies should cool on the pan, placed on a rack. Once cool, they may be decorated, and then stored in a covered airtight container.

See also butter; drop cookies; eggs; flour; icing; and pressed cookies.

Rombauer, Irma Starkloff (1877–1962), and her daughter, Marion Rombauer Becker (1903–1976), were authors of the Joy of Cooking, one of the most important twentieth-century American cookbooks. First published by Rombauer at her own expense in 1931, it grew to become both a beloved national institution and (under Becker) a prodigious one-of-a-kind kitchen encyclopedia.

From the outset, the St. Louis–born mother and daughter’s Midwestern German roots strongly influenced the selection of material, particularly regarding sweets. Both women loved a wide range of American cakes, pies, confections, and other desserts, from brownies to persimmon pudding. But they remained especially devoted to the pastry and dessert traditions of the German-speaking community in which they had grown up. Through Joy they introduced many American cooks to—among other things—German Christmas cookies (Lebkuchen, Springerle, “Cinnamon Stars”), Linzer Torte, almond torte, hand-stretched strudel, and sweetened yeast-raised cakes like Kugelhupf and Dresdner stollen.

The authors always remained vigilantly up to date on new developments in cakes, pastries, candies, and ice creams. In 1936, long before rival kitchen bibles like The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book had mentioned electric mixers, Rombauer was giving directions for mixer-method cakes. When Becker took over the work (from 1962 to 1975), she added great amounts of useful technical information on the properties of different flours, sugars, fats, and kinds of baking pans. She deleted a considerable amount of older material derived from manufacturers’ proprietary formulas. Seeking to expand the work’s international focus, she also introduced many new recipes, including genoise, chocolate mousse, baklava, and Turkish delight.

For all of Joy’s credentials as a distinguished teaching tool and reference work, the quality that its admirers most treasured during Rombauer’s and Becker’s lifetimes was an engaging conversational verve that moved one early user, the popular illustrator James Montgomery Flagg, to describe it as “the first cookbook that could be called human.”

See also brownies; farmer, fannie; gugelhupf; pans; springerle; and stollen.

Rosh Hashanah is the Jewish New Year. The anniversary of the Creation, it is a time for self-examination and repentance. Ancient people had no organized New Year, but rather calculated the year from the new moon nearest to the beginning of the barley harvest in spring (at Passover) or to the ingathering of the fruits (Sukkot) in autumn. Rosh Hashanah, which is celebrated in early autumn, was eventually adopted as the beginning of the festal year, and today it is one of the great solemn days in Judaism. See judaism.

The Rosh Hashanah table is laden with delicacies representing optimism for a sweet future. Dishes abound with honey, raisins, carrots, and apples—all sweet seasonal reminders of hope for the coming year. At the commencement of the Rosh Hashanah meal, Jews around the world say a blessing over an apple, symbol of the Divine Presence, dipped into honey to augur a sweet year. Some Jews also eat a date or a pomegranate. Lekakh, Yiddish for honey cake, is the traditional eastern European cake served on the first night of Rosh Hashanah; it is also eaten as a sweet throughout the year. Today, honey cake, once a simple honey-infused cake, has taken on a more gourmet aspect with the addition of chocolate, ginger, apples, or apricots. In North African Jewish communities, dainty finger pastries oozing with honey syrup, shaped like rolled cigarettes, are served. In the Ottoman Empire, baklava with a sugar or honey syrup were served. See baklava. Zelebi, snail-like rolls of dough dipped in honey, are served in Persian and Iraqi communities. Although apple desserts abound at Rosh Hashanah because of the apple’s symbolism, the South German and Alsatian tradition of serving an Italian plum tart called Zwetschgenkuchen has become increasingly popular.

rosogolla, often spelled rasgulla, is a popular Indian ball-shaped sweet prepared from chhana (fresh milk curd) soaked in sugar syrup. These moist treats are a common sight at sweet shops across the subcontinent. In India, rosogolla is primarily associated with West Bengal, where it is just one, if perhaps the best known, of numberless chhana-based sweets. Chhana from cow’s milk is considered best for rosogolla. To make chhana, acid—most traditionally the whey from a previous batch—is added to hot milk to coagulate it. Once the curds are drained, artisans take extreme care to squeeze out any excess water. The mixture is traditionally kneaded by hand on a wooden board, although kneading machines are now common. The chhana is rolled between the palms to form small balls, which are then cooked in sugar syrup. Though the ingredients are simple, the technique demands considerable skill. In Mistanna Pak, a two-volume compendium of sweets published in 1906, Bipradas Mukhopadhyay cautioned readers to be attentive while boiling the chhana balls. After adding the balls to the bubbling sugar syrup, cold water must be sprinkled over them to prevent them from crumbling—a common defect.

More recently, sweet makers have been experimenting with flavors like chocolate, orange, and others to give rosogolla a new twist. One such interesting innovation is the now-famous baked rosogolla available in Kolkata at Balaram Mullick. Those on a diet can enjoy low-calorie rosogolla.

There are various claims and counterclaims regarding the origin of the sweet, and the argument is often as heated as it is esoteric. Some believe that rosogolla was first prepared by the sweet makers of Odisha, while others insist that it was invented in Bengal. The most common view is that Nobin Chandra Das invented the sweet in Kolkata (Calcutta) in 1868; there is even a plaque commemorating the spot. See kolkata and nobin chandra das. Sweet makers are called moira in Bengali, as are the caste members (part of the Nabasankha group) associated with confectionery and sugar production. The story goes that Nobin Moira came from a family of sugar traders that had fallen on hard times. After at least one false start, in 1866 he opened a sweet shop in the Bagbazaar district of North Kolkata. Two kinds of sweets were popular among the patrons: sandesh and sweets made of dal (lentil) or other flour. See sandesh. As related in a booklet called Sweetening Lives for 75 Years, published by K. C. Das, the patrons were bored and demanded something different, so Nobin came up with “Sponge Rosogolla.” The sweet gained popularity following a visit by the wealthy businessman Bhagwan Das Bagla to Nobin’s shop. Nobin offered Bhagwan Das Bagla’s thirsty son rosogolla along with some water, and the sweet’s fame soon spread far and wide.

Though Calcutta’s Nobin Moira is popularly called the Columbus of rosogolla, the food historian Pranab Ray, in his work Banglar Khabar (1987), points out that by 1866, Braja Moira had already introduced rosogolla in his shop near Calcutta High Court. Yet another tale claims that Haradhan Moira invented rosogolla in Phulia, some 50 miles to the north of Kolkata. Haradhan Moira used to prepare sweets for the local zamindar, a feudal lord who could collect taxes from the villagers. One day a little girl from his household visited the sweetshop, and she was crying. To comfort her, Haradhon Moira dropped a ball of chhana into some piping hot sugar syrup, and rosogolla was born. Claims to the origin of rosogolla do not stop here. Gopal Moira from Burdwan district created a sweet similar to rosogolla, called gopalgolla. Mistikatha, a newsletter published by the West Bengal Sweetmeat Traders Association, points out that many other artisans prepared similar sweets carrying a variety of names, including jatingolla, bhabanigolla, and rasugolla.

While debates regarding rosogolla’s origins continue, it is important to note that Nobin Moira’s enterprising son Krishna Chandra Das and grandson Sharadacharan Das were instrumental in putting rosogolla on the global map, thanks to their innovative technique for making canned rosogolla. In 1930 Krishna Chandra Das opened his own shop with his younger son Sharadacharan Das. When Sharadacharan Das took over the business after his father’s death, he incorporated the shop as a company, and in 1946 he rechristened it K. C. Das (P) Limited. He was instrumental in designing the steam-based cooking technology used in the K. C. Das factories in Kolkata and Bangalore. Yet even if canned rosogolla is available anywhere, and anytime, the best rosogolla remains a piping hot one straight from the kitchen, cooked late in the evening in a local Bengali sweet shop. Even better is rosogolla soaked in sugar syrup prepared from nalen gur (date palm jaggery), a treat available only from October to December. See palm sugar.

rugelach are crescent or half-moon-shaped cookies usually made with a cream-cheese dough. Although popular for Hanukkah and Shavuot (the holiday celebrating the giving of the Torah), they are also eaten throughout the year. The name likely derives from the Yiddish or Slavic rog, meaning “horn,” with the addition of lakh, the diminutive plural. Originating in Eastern Europe, and related to Schnecken (sweet buns), Kipfel (bread crescents), and Kupferlin (almond crescents), rugelach are now probably the most popular American Jewish cookies.

Rugelach dough was originally made with yeast, butter, and sour cream, but in the United States, thanks to the popularity of Philadelphia brand cream cheese, it evolved into the short cream-cheese pastry most often encountered today. According to Gil Marks in The Encyclopedia of Jewish Food, the first known recipe for rugelach with a cream-cheese dough appeared in The Perfect Hostess, written in 1950 by Mildred O. Knopf, sister-in-law of the publisher Alfred A. Knopf. Mrs. Knopf explained that the recipe came from Nela Rubinstein, wife of the famous pianist Arthur Rubinstein. But it was Mrs. Knopf’s friend Maida Heatter who put rugelach on the culinary map in 1977, when she published her grandmother’s recipe in Maida Heatter’s Book of Great Cookies. This recipe remains the most sought after of all Mrs. Heatter’s recipes and is the prototype for the rugelach most often found today in upscale American bakeries and discount stores like Costco. Like doughnuts and bagels, rugelach now come in a multitude of flavors, even jalapeño, although the most popular are chocolate and apricot. For those who obey the Jewish dietary laws, pareve versions of rugelach using soy-based Coffee Rich creamer and margarine instead of cream cheese are also available.

See also hanukkah and judaism.

rum, sometimes spelled rhum, is the generic term for alcohol distilled from fermented sugarcane, either in the form of cane juice or cane-based molasses. Once Europeans began cultivating sugar in their colonies in the 1400s, it was inevitable that rum would be invented. Sugar had previously been imported to Europe from the Arab world, where distilling was used primarily to refine medicines and perfume, since drinking alcohol is prohibited to Muslims. In Western Europe, where there were no such restrictions, distilling was a common skill, and there was a brisk trade in brandy and other liquors known under the collective name of aqua vitae, or “strong waters.” It was common knowledge that most sweet liquids could be fermented and distilled, so it is surprising that the Europeans did not make rum for over a hundred years after sugarcane first became available to them.

It is very difficult to pinpoint the first instance of alcohol distilled from sugarcane. The cocktail historian David Wondrich cites the Indian historian Ziauddin Barani, who wrote in 1357 that a sultan of Delhi, who died in 1316, had prohibited the distillation of wine from granulated sugar. That lone reference aside, the next appearance of rum is in the mid-sixteenth century, when plantation workers in the Portuguese colony of Brazil ran sugarcane juice through a still to make low-quality rum. The first mention of this drink is in a report by Governor Tome da Souza of Bahia, who wrote in 1552 that the slaves were more passive and willing to work if allowed to drink cachazo. That term, which is colloquial Portuguese for a low-grade alcohol typically used for pickling, signals the quality of the resulting beverage. The first detailed description of the Brazilian rum called cachaça, from George Margrave’s Historia Naturalis Brasiliae of 1648, calls it “a beverage fit only for slaves and donkeys,” revealing that the drink had not been improved in almost a hundred years.

In the Portuguese, Spanish, and French colonies in the New World, rum remained a crudely distilled beverage for centuries. In those countries, powerful aristocrats held monopolies on distilling brandy, and they wanted no competition from other spirits that might reduce the value or volume of their exports. In 1647 the Portuguese government ordered that only slaves were to drink cachaça; since slaves had no bargaining power, there was no incentive to make a better product. For hundreds of years cachaça was made in crude stills and stored in clay jars that imparted an earthy flavor; it was not until the late nineteenth century that any concerted attempt was made to improve it.

The situation in the British colonies was different, as the mother country had no valuable trade in distilled alcohols and no incentive to suppress new drinks. The first mention of rum in English is in a letter from the colony of Barbados in 1651, which states, “The chief fuddling they make in this island is Rumbullion alias Kill-Divil, and this is made of sugar canes distilled, a hot hellish, and terrible liquor.”

As there was no suppression of the trade, local sugar planters started experimenting and quickly realized the commercial potential of fermenting molasses, a byproduct of sugar refining. See molasses and sugar refining. There was little demand for molasses in the 1500s, since the sticky liquid was much more difficult to transport than crystalline sugar and had a heavy and less desirable flavor. Some molasses was used as a sweetener by slaves and the poor who lived near plantations; the rest was usually dumped into rivers. As molasses was a product with a longer shelf life than sugarcane juice, and one that had previously been thrown away, the economic advantages of using it were obvious. As it happened, the caramelized flavor of molasses made more desirable rum, with a smoky sweetness to balance the harsh spirit.

Demand for the new drink grew, but the islands were not the best place to make rum in volume, as there was a limited amount of timber to feed the fires of the distilleries. A solution beckoned—ship the molasses to fellow British colonists in New England, where there were unlimited forests and a supply of skilled labor, in exchange for codfish, meat, grain, and other foodstuffs that were expensive or unavailable in the Caribbean. By 1657 a thriving rum trade had developed between the southern and northern colonies, causing the General Court of Massachusetts to declare overproduction a problem. A market was quickly found, as rum became one of the components of the Triangle trade that brought molasses from the Caribbean to be made into rum and exchanged for slaves to work the sugar plantations. See plantations, sugar and slavery.

Rum became an integral part of trade inside the colonies, which had a chronic shortage of English hard currency. Wages were paid and land sold for prices denominated in gallons of rum, and it became the primary trade good with the native tribes. Rum also became part of the colonial American medicine chest, recommended to purify stale water, ward off diseases of “foul air,” and banish chills in winter. It was drunk recreationally in many ways—mixed with warm molasses to make a beverage called blackstrap; with berries and vinegar in drinks called shrubs; with hot cider for wassail; and with cream, eggs, and beer to make flips. See egg drinks.

It was in colonial America that rum was first used in cooking, notably in cakes involving rum raisins, apple tansy pastries, and rum and berry sauces. One questionable item is the rum cake in which fruit is candied and mixed with the batter before baking, followed by the cake being soaked in rum and aged before consumption. Though this is allegedly an American variant on a British steamed pudding said to be popular since the seventeenth century, the oldest surviving recipe is from the 1840s. There are also claims that this item originated in Bermuda or Jamaica, but in all cases contemporary documentation is lacking.

A more authentic eighteenth-century rum dessert—though one that is remarkable to modern diners—is the omelette filled or topped with rum-apricot sauce and sprinkled with powdered sugar. This recipe was popularized by Thomas Jefferson’s cook James Hemings after he left Jefferson’s service, and was one of many items made with fruit sauces cooked with rum. The most common dessert in colonial America was probably Indian pudding with hard sauce—a steamed pudding made with cornmeal, milk, and molasses topped with a glaze of rum, butter, and sugar. See pudding.

It is difficult to determine accurately when rum was first used in cooking, because many recipes merely specified a “hard sauce” that could be made with rum, whiskey, or brandy, depending on what was available. The rums and whiskeys of the 1700s were all similar in that they were harsh and unaged when typically consumed. (Although it was known at least as early as 1737 that aging improved rum, this step was left to purchasers; for makers to barrel-age and mellow spirits before selling them was not common practice until the 1830s.) It is difficult to accurately recreate early recipes involving rum because it is almost impossible to find rum as bad as the best that could be had in that era.

Once rum was improved by aging, Europeans began drinking it in punches and investigating how it might be further used in cooking. See punch. Rum production in all colonies of the British Empire was spurred when the navy adopted rum as the tipple of choice; it replaced a brandy ration for which the principal supply came from France. The army followed, and the switch kept British government commerce inside British colonies. Rum was made in 1793 in Australia and in India in 1805.

The first European culinary hit involving rum was the baba au rhum, based on a traditional Polish yeast cake and invented by exiles in Paris in 1835. See baba au rhum. A variant on this dessert, with lemon juice and rum in equal amounts, is a specialty of Naples. Rum balls were invented around 1850, probably in Germany, where they are called Rumkugeln. The basic recipe of rum, coconut, and chocolate spread to England, where the confection became a Christmas specialty, and around Europe, where many regional variations developed. In the twentieth century, desserts based on rum and coconut became popular worldwide, and in Mexico, coconut rum sauce was added to the traditional tres leches cake for a regional hit. See tres leches cake. Elsewhere in Latin America, rum-cinnamon sauces laced with star anise were first recorded as cake glazes in Colombia in the early twentieth century, along with a cake called pastel borracho, made with rum, prunes, and crème anglaise. See custard.

The late twentieth century saw a proliferation of rum brands and styles, along with greatly increased sophistication among consumers, and the use of rum in sweets has expanded correspondingly. Brands now on the market range from those with vodka-like clarity to heavily aged styles with the depth and smokiness of Scotch whisky, giving rum drinkers unparalleled choice, and cooks a wide palette of flavors to work with.

See also sugarcane and sugar trade.

Russia was famed in medieval times for its wild hives, so abundant that travelers tell tales of honey dripping right from the trees. See honey. Although sugar eventually supplanted honey for preserving and baking, the Russians remain devoted to honey’s taste and nutritive powers.

The Domostroi, a sixteenth-century book of household management, describes several different types of mead, all fermented from wild honey: boiled, white (made from light, clear honey), honey (with a greater proportion of honey to water), ordinary, boyars’ (the honeycomb was left in for the initial fermentation), spiced, and berry. See mead. Berry meads offered the further advantage of preserving large quantities of perishable summer fruits. Another old honey-based drink is sbiten’, for which honey is heated with water and spices, and sometimes fortified with vodka or brandy.

As sugar gradually entered elite kitchens in the second half of the seventeenth century, the Russians clearly distinguished between preserves made with honey and those made with sugar. Most prized of all were the honey’s “tears”—the pure liquid that drips naturally from the comb. The Russians made other sweeteners by boiling down fruits such as grapes and watermelon into syrup known generally as patoka (a word later used to describe molasses, a byproduct of sugar refining). See pekmez and molasses. Patoka was used to preserve nuts, ginger root, fruits, and even vegetables like carrots, turnips, and radishes, by cooking the foodstuff gently in the syrup until glistening. Sugar-rich vegetables like beets, pumpkin, and carrots were turned into paryonki, chewy treats made by baking the thinly sliced vegetables at low heat until their sugars caramelized, then air-drying them.

The Russians relished fresh apples, cherries, pears, plums, melons, and berries in season, eating them fresh, baking them (especially apples), and using them to sweeten porridge. The seventeenth-century German scholar Adam Olearius described an exquisite Russian apple with flesh so translucent that when held up to the sun, the seeds could be seen right through the skin (this was probably the Yellow Transparent apple). Fruit not eaten fresh was put up for preserves or used to flavor a wide range of cordials and liqueurs.

Once they gained access to sugar, wealthy households also frosted and glacéed fruit. Grapes, gooseberries, lingonberries, cranberries, and currants were dipped in beaten egg white, then rolled in fine sugar and dried slightly in a warm oven. Apricots, peaches, pears, cherries, and sweetmeats such as plums stuffed with nuts were cooked lightly in syrup, then dusted with crystalline sugar to create jewel-like confections known as “dry Kiev jam” (analogous to the “dry” suckets of Elizabethan kitchens, distinct from the “wet” confections preserved in syrup). See candied fruit. Catherine the Great took such a liking to these candied fruits that in 1777 she issued an edict requiring that hundreds of pounds be supplied to the court. Fruit juice was boiled into ledentsy, clear, hard fruit drops. In the homes of the wealthy, all of these sweet foods, known collectively as zayedki, were served at the end of the meal, in a special course.

Dried fruits and nuts, including raisins, apricots, cherries, dates, prunes, almonds, walnuts, and hazelnuts, were also enjoyed as zayedki. See dried fruit. Local stone fruits were dried in the great Russian masonry stove. More exotic fruits were initially brought by caravan from China and Central Asia, but as Russia’s territorial ambitions expanded, so did access to produce. Beginning in the seventeenth century, territory stretching east to Siberia and Central Asia, south to the Caucasus, and west to the Baltic states came under the empire’s control; in the twentieth century the Soviet Union covered one-sixth of the world’s landmass, giving Russians access to all sorts of Eastern fruits and confections, including figs, sultanas, halvah, and lokum. See halvah and lokum.

Traditional Sweets

In addition to a wide range of preserves and beverages, Russians prepared other types of sweets, although it must be stressed that for the most part these treats were reserved for the well-to-do, as the serfs, and later the peasants, subsisted on meager grain-based diets; only on feast days and major holidays like Easter were they able to indulge. Pastila is among the most distinctive: puréed, sweetened apples are whipped with egg whites and dried slowly in the oven to form a light confection. See pastila. An old term for fruit leather is levashniki. Fruit, usually berries, was cooked with patoka and puréed, then spread into a thin layer and dried. See fruit pastes.

Excellent cakes were baked in the masonry stove as the temperature fell after bread baking. The most widespread, and still popular today, are pryaniki, firm gingerbread shaped into decorative forms, either by hand or in wooden molds. See gingerbread. Originally made with rye flour, honey, and berry juice, Russian gingerbread dates back to pre-Christian times; spices were added in the Middle Ages. Variations include medovik and kovrizhka, both of which call for a higher proportion of honey that yields a more pronounced honey flavor.

Holidays featured special foods. From pagan times, even before Russia adopted Christianity in 988 c.e., bliny (or blini, yeasted pancakes made with a variety of flours) were baked to mark the return of the sun in late winter; they are also a symbolic funeral food. Though not intrinsically sweet, bliny in the nineteenth century were also encountered in a Europeanized, crêpe-like form spread with jam or honey (chocolate is often used today). Another ancient holiday dish is kut’ya, wheat berries cooked with honey, poppy seeds, and nuts and served with dried fruit compote at Christmas. In some families, a spoonful of the honey-soaked grain was tossed up to the ceiling. If it stuck, the next season would bring a bountiful harvest. See wheat berries. At Easter, paskha (a rich, sweet cheesecake) and kulich (a tall, yeasted, enriched loaf) celebrate the end of the 40-day Lenten fast. See easter and breads, sweet.

Russia Meets the West

Although sugar had been known in Russia as early as the thirteenth century, traditional sweets were, until centuries later, made with honey or another liquid sweetener. Demand for sugar rose only in the mid-seventeenth century, when the use of tea became more widespread. Imported at great cost, chiefly through the far northern port of Arkhangelsk, sugar remained a luxury available only to the wealthy. Russia’s first domestic sugar refinery opened in Saint Petersburg in 1719, at Tsar Peter the Great’s prompting. By the end of the eighteenth century, Russia had 20 sugar factories, and the first factory for refining sugar beets was built in 1802. By 1900, Russia was one of the world’s great sugar producers. Nevertheless, devout Russians were reluctant to accept sugar in any form, since it was commonly refined with blood and therefore forbidden for fast days, which number nearly 200 in the ecclesiastic year.

Thanks to Peter the Great’s westernizing reforms, the eighteenth century witnessed profound changes in all aspects of Russian life, including cuisine. If, when Peter took the throne, the affluent were still enjoying zayedki at the end of the meal, by the mid-eighteenth century they were eating desert (dessert), a cognate pointing to high society’s growing infatuation with all things French. See dessert. The nobility began to employ foreign chefs, who accelerated the introduction of new dishes and methods of preparation. By the mid-nineteenth century the Russian elite regularly consumed desserts from the classical European repertoire, such as macédoine de fruits, Viennese torte, and chestnut croquembouche. See croquembouche. Other creations, like Guriev kasha, were a hybrid of Russian and French practices. See guriev kasha.

Churned ice cream arrived from the West at the end of the eighteenth century. See ice cream. However, Russians had long enjoyed their own frozen dairy treat in the form of molochnaya stroganina, made by freezing fresh, rich milk and shaving long, thin strips off the mass with a sharp knife (this process is used today to make an appetizer of frozen fish). Stroganina was a seasonal treat made possible by the winter cold. Even today Russians eat ice cream outdoors year round.

The Soviet Period

In the aftermath of the 1917 Revolution, food became an ideological tool. Candy was particularly useful, since it was now produced for the masses, often for educational purposes. “New Weight” candies introduced the metric system in a pleasing way. Wrappers for “Red Army” candies, with Russian Civil War images and catchy rhymes, were designed by the great poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. The consumption of candy, once considered nonessential, became a cultural imperative.

Chocolate, however, remained a symbol of bourgeois decadence, providing fodder for Alexander Tarasov-Rodionov’s classic early Soviet novel Chocolate (1922), which chronicles the downfall of a functionary through the twin temptations of chocolate and lust. But with Stalin’s mid-1930s campaign to make life “better” and “more cheerful,” chocolate was promoted, along with champagne, as proof that the Soviet Union could provide its proletariat with luxury goods. Nine chocolate factories were built under the Five-Year Plans, and vast amounts of cacao beans were imported for domestic production.

Although Soviet champagne and chocolates never achieved high quality, ice cream undeniably contributed to the betterment of Soviet life. In 1936, Anastas Mikoyan, the minister of foreign trade, toured the United States, where he became enthralled with American ice cream–making technology. See ice cream makers. Seeing an opportunity to overtake America in ice cream production, he immediately imported the necessary equipment, and the first Soviet ice cream factory opened in 1937. Mikoyan decreed that every Soviet citizen should eat no less than five kilos of ice cream a year.

Despite the Soviet Union’s chronic food shortages, hard candies—distinguished by colorful, charming wrappers—were never in short supply. Other Soviet-era treats included a marshmallow-like confection called bird’s milk, and sweet soy sticks made by the Red Front candy factory. See bird’s milk. Nevertheless, Russians continued to be avid makers of jams and preserves at home, for winter sustenance. When President Mikhail Gorbachev introduced sugar rationing in 1988 to stem the production of moonshine, consumers began hoarding sugar, one of the few reliably available products. Sugar virtually disappeared from the stores, at which point Muscovites were assured three kilos apiece during the jam-making season as a goodwill gesture.

Post-Soviet Russia

After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the market was flooded with brightly packaged foreign brands, and Western fast-food chains appeared. Snickers candy bars were sold at kiosks alongside the suddenly old-fashioned-looking hard candies. McDonald’s brought milkshakes to Moscow in 1991 (although the Russians had enjoyed their own version for decades), and Dunkin’ Donuts arrived in 2010, displacing the city’s iconic outdoor doughnut stands. See dunkin’ donuts. But the past was not forgotten. When, in 2000, the Brooklyn-born chef Isaac Correa opened a popular fusion restaurant in Moscow, he called it The Hive. The restaurant’s signature was gorgeous honey presented in sake cups with tea. Harking back to a profligate past was the restaurateur Arkady Novikov’s dessert of “wild” strawberry soup, made from berries grown throughout the winter in greenhouses.

Russians today are attempting to resurrect many treasures of Russian cuisine that had disappeared during the 70-odd years of Soviet rule. Young entrepreneurs are bringing renewed attention to such beloved sweets as pastila, preserved fruits, and of course, special honeys.