The Pacific Northwest (U.S.) includes the entire northwest corner of the United States and Canada. The region is prized by cooks for its superior tree fruits, nuts, and berries. The lush valleys of British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon form a large, fertile growing region that is sandwiched between the Coastal range on the west and the rugged Cascade and Rocky Mountain ranges on the east, stretching over 400 miles north to south. The area’s dry and sunny days and cool nights are optimal for flavor and color development and mean fewer disease problems. Crops grow slowly and develop rich, complex flavor profiles.

Wild fruits and nuts grow in abundance throughout the region and were a food source for Native Americans. Many fruits were dried and used to supplement their meals during the long winter months when food was scarce. See native american. By 1830, early settlers could plant their own crops from seeds purchased at Hudson Bay Company outposts. Eighteen years later, the first commercial crops were planted in Oregon’s Willamette Valley after Henderson Luelling and his brother, Seth, transported 700 grafted fruit trees, bushes, and berries planted in the beds of their wagons over the Oregon Trail. “Bing,” the main variety of cherry produced in the United States, was named in 1860 after nurseryman Seth’s Chinese foreman, Ah Bing, who grafted the tree on which they grew. Today, in the summer, fresh Bing cherries are often made into a compote with local raspberries, blackberries, and blueberries and served over chiffon or pound cake, or barely cooked with a small amount of sugar and a splash of local eau-de-vie for a sauce for ice cream.

Another popular ice cream topper is local strawberries. The industry was born when farmers started growing strawberries as a crop while they waited for their newly planted fruit trees to reach maturity. The berries thrived, and in 1870 Asa Lovejoy opened the first cannery and began shipping berries across the country to the East Coast. In 1920, Oregon and Washington were the first to develop the preservation of fruit by freezing strawberries in barrels, which were then shipped by rail to East Coast preserve factories. Today, although the much-anticipated strawberry crop is small, it is still considered a regional treasure, and the sun-ripened berries are cherished by locals for their excellent flavor and juicy flesh that is a brilliant red inside and out. During the season, most dessert tables will feature them in some form—strawberry shortcake, strawberry pie, or fresh strawberry sauce over homemade ice cream. With strawberries’ exceptionally short season, these simple old-fashioned desserts have remained favorites because they showcase the berries and bring out the best of their luscious flavor. See pie; sauce; and shortcake.

Almost all of the nation’s commercial blackberries and black raspberries, and a high percentage of the red raspberry and blueberries, are grown here. Many blackberry cultivars, like the highly regarded “Marion” (commonly called marionberry), tayberry, and loganberry, are prized by local cooks for their excellent flavor. Fresh raspberries are available locally during summer and into fall, as well as high-bush blueberries, which grow in the same regions.

With the abundance of fresh berries available locally in the Pacific Northwest, desserts served during June and July always feature fresh berries in one form or another. The best blackberry pie is made with the flavorful wild Pacific trailing blackberry, but more often it is made with commercially grown berries like Marions, a regional favorite. The fine flavor of Marions is so intense that this simple old-fashioned dessert needs only sugar, a splash of lemon juice, a thickener, and pastry to make an exceptional sweet ending.

Cobblers and crisps made with berries, fruits, and nuts, or a mixture of them depending on what is in season, are also widely popular. Cobblers are most commonly made by tossing the fruit with sugar and a thickener, topping with a short pastry, and baking until the crust is a rich golden brown. However, they are also served with a cooked fruit filling with tender biscuits baked on top. See fruit desserts, baked.

The most traditional Pacific Northwest desserts—pies, cobblers, crisps, and cakes—are made with the beloved native wild huckleberry. Twelve species grow in the Pacific Northwest and one of them—the sweet purple berries of Vaccinium membraceum—was a significant industry a hundred years ago. From mid-August to mid-September, large huckleberry camps were set up near ancient huckleberry fields, where families picked and often canned huckleberries on the spot. Professional pickers sold their berries to a distributor, who hauled the berries to urban markets for resale and processing.

Native Americans have gathered huckleberries in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest near Mount St. Helens for thousands of years. The berries, picked and dried on tule (rush) mats in front of a smoldering log, were eaten with dried game and fish throughout the harsh winters. During the Depression, as more and more unemployed workers left the cities for the mountains in hopes of making enough money picking huckleberries to feed their families, a conflict arose with the Native Americans whose ancient berry picking fields had been invaded. They took their grievance to the U.S. Forest Service, and the issue was resolved with the Handshake Agreement of 1932 that reserved a portion of the Indian Heaven Huckleberry Fields solely for Native American use during the season. The treaty is still being honored today, and huckleberry pie is still as popular today as it was a hundred years ago. It is the quintessential Pacific Northwest dessert.

Besides the wide variety of wild and commercially grown berries, there is also a thriving tree fruit industry, including apples, pears, cherries, apricots, plums, and peaches.

From mid- to late summer and into fall, when tree fruit are perfectly ripe and harvested, local dessert choices expand exponentially. Sweet cherries, peaches, nectarines, pears, and apples are transformed into mouth-watering desserts that tend to be rustic rather than fussy, with the fruit occupying center stage. Apple crisp is popular, baked with blackberries, huckleberries, or chopped hazelnuts, while pears are often poached in spiced red wine or used as a main ingredient in cakes. It is also not unusual to find tree fruit served as a last course with locally produced cheese and nuts, following the French tradition. Local apples, cherries, and plums, as well as several berries, are made regionally into eau-de-vie, which is often served with sweets for dessert.

Almost all of the country’s hazelnuts are grown from the very southern end of Oregon’s Willamette Valley into southern Washington. The orchards are distinguished by the deep emerald green canopy that protects the nuts when, in late September or early October, they drop to the ground when ripe. These premier nuts are best known for their large size and superior flavor, making them a favorite of chefs. Chopped hazelnuts are widely used paired with chocolate or fall fruits—hazelnut chocolate mousse, pear and hazelnut tart, and hazelnut apple crisp can often be found on regional menus. Ground hazelnut flour is a favorite of pastry chefs when they want a rich, nutty pastry or a gluten-free substitute for wheat flour.

Ice cream is still as popular a dessert now as it was a hundred years ago. In the past few years, there has been an increase in small, independent ice cream producers who use local ingredients in ice creams, such as Honey Balsamic Strawberry with Black Pepper Ice Cream or Melon Ice Cream with shards of razor-thin prosciutto. See ice cream.

Sweet endings in the Pacific Northwest appear to have new beginnings.

See also dried fruit; fruit; fruit preserves; nuts; and united states.

palm sugar is one of the world’s oldest sweeteners, distinguished from cane sugar in Singhalese chronicles dating from the first century b.c.e. It is produced and consumed across a swath of Asia stretching from the Philippines to India and Sri Lanka. For anyone accustomed to thinking of sugar as either white or brown and just plain sweet, palm sugar is surprising in its complexity, ranging in color from pale yellow to almost black and with a flavor that, in addition to sweet, can be salty, sour, bitter, smoky, or any combination thereof. See sugar.

Palm sugar is produced by boiling sap collected from the cut inflorescence of many palm varieties, including palmyra (Borassus flabellifer), coconut (Cocos nucifera), kithul or fishtale (Caryota urens), date (Phoenix dactylifera), silver date (Phoenix sylvestrus), aren (Arenga pinnata), and nipa (Nypa fruticans) palms. Prior to cutting, the inflorescence is softened by beating with a stick or mallet to initiate the flow of sap. The sap is captured in tubes suspended beneath the cut inflorescence and collected twice a day; tappers often add a fermentation prohibitor such as lime, calcium carbonate, or tannic bark. Some tappers and sugar makers (often one and the same individual) include a ritual as part of the sap collection process. On northern Sumatra, ethnic Batak, most of whom are Christian, request permission from God before collecting sap. On Bali, it is believed that if the tapper speaks with or is spoken to by anyone while transferring collected sap to the pan where it is to be boiled, the sugar will become spoiled.

Once collected, the sap is reduced by evaporation, boiled and stirred for several hours in large, uncovered cauldrons. During boiling, some makers add ingredients to alter the color of their sugar; for example, Batak add the spongy reddish fiber that lines the inside of mangosteen peels to make their product darker. Once the sap has been sufficiently reduced, usually to a viscosity somewhere between the soft- and hard-ball candy stage, it is poured into molds made from coconut halves, bamboo tubes, strips of rattan joined to form a circle, and other materials, and left to cool and solidify. See stages of sugar syrup. In southern Thailand, the sugar is whipped with large whisks until it is stiff, then formed without the use of molds into lumps or swirl-topped mounds and left to dry. In Sarawak and Sabah states on Malaysian Borneo and on Sri Lanka, the sugar is taken from the fire when still liquid, allowed to cool, and then poured into jars, tubs, or bags.

In local languages palm sugar might be named for its color (gula merah or “red sugar” in Indonesia), its traditional provenance (gula jawa in Indonesia, gula Melaka in Malaysia), the variety of palm from which it is made (gula nipa and gula aren in Indonesia, gula apong or “floating sugar” on Malaysian Borneo, in reference to the nipa palm, which grows in water), or the sugar-making process (pakaskas in the Philippines from kaskasin, which refers to the process of “scraping” the sugar from the boiling sap). Palm sugar is duong thot not in Vietnamese and scor thnout in Khmer. In India, it is called gur or, confusingly, date sugar (whether or not it is made from date palms) or jaggery, a word that also refers to dark brown cane sugar.

No matter which palm it is made from, palm sugar has a lower glycemic index and is less sweet than cane sugar. The palm sap that becomes sugar has also long been used to make intoxicating toddy and distilled arak, as well as vinegar. Palm sugar is an ingredient in a staggering variety of sweet and savory foods, from Thai somtam (green papaya salad) to innumerable Indian sweets.

See also india; maple sugaring; philippines; south asia; southeast asia; sticky rice sweets; sugar and health; and thailand.

See sponge cake.

pancakes are thin, flat cakes made by pouring or ladling a liquid batter onto a hot greased surface, and baking them there until done. The simplicity of the required ingredients and equipment means that pancakes are one of the most ancient foods created by humans. Pancakes called tagenites made from wheat flour and soured milk and served warm with honey are mentioned in Greek writings from the fifth century b.c.e., but it is generally accepted that some form of pancakes has been made since prehistoric times.

Pancakes Large and Small

Two key features distinguish pancakes from other starch-based staples. The first is that liquid batter (at times very thick) is used, in contrast to the firm dough required for shaping bread. The second is that gluten is not required for successful formation—indeed, gluten is not generally desirable, as pancakes are intended to be soft, not stiff—which means that a much greater range of grains can be used.

Flour or meal made from true cereal grasses, such as wheat, oats, barley, rye, maize, and rice, collectively form the base of most pancakes eaten around the world. The grain-like seeds of plants that are not technically grasses, such as buckwheat (related to rhubarb) and amaranth (related to pigweed), and starches derived from many other seeds and plants, such as pulses (peas, beans, lentils), potato, cassava (tapioca flour), and chestnuts, may also be used. This enormous flexibility in the basic ingredient has led to pancakes being a truly global food—one that has crossed the East–West culinary divide in a way that bread has not.

The basic pancake batter may be varied in an almost infinite number of ways. It may be plain and simple, rich and sweet, or spicy and savory. Additional ingredients such as berries, nuts, or chocolate chips may be included in the batter, or the cooked pancake may be folded or rolled around a filling (sweet or savory), or served with a sauce alongside. The batter may even be colored, either artificially or with such natural ingredients as beet juice, spinach juice, or turmeric.

In terms of thickness, pancakes fall into two broad groups. The thin, unleavened form is exemplified by the classic French crêpe and embraces many European specialties (most of which are sweet dishes), such as the palatschinken of Central and Eastern Europe, Poland’s naleśniki, and Spanish frixuelos. The thicker, fluffier, leavened type is that of the American hotcake, Australian pikelet, Scottish drop scone, and Russian blini (yeast-raised, classically made from buckwheat, and often savory). Many other national specialties fall somewhere between these styles, for example Austrian Kaiserschmarrn (characteristically shredded before serving), German Pfannkuchen (the word can mean both pancake and doughnut), Czech livance, and Danish æbleskiver (plump, round balls that traditionally contain an apple filling).

The diameter of the pancake depends on personal and national preference, and is limited only by the diameter of the cooking pan or surface. The pikelet of Australasia is a few bites in size, and several are cooked at the same time in the pan, whereas Ethiopian injera may be several feet across, with a single pancake ample enough to satisfy several people. In some countries special pans have been devised with indentations for cooking multiple pancakes at once, such as Denmark’s æbleskiver and Sweden’s plättar.

Pancakes may also serve as the base for other dishes, especially cakes. Gâteau mille crêpes (thousand crêpe cake) consists of a large stack of thin crêpes sandwiched together with a sweet filling, which is then cut into slices like a cake. Hungary’s rakott palacsinta is not dissimilar. In Russia, blini are layered with farmer’s cheese and dried fruit, or sometimes simply jam, to make a tall blinchatyi pirog.

Cooking Pancakes

Although the word “pancake” is attested in English since the beginning of the fifteenth century, the exact characteristics covered by this name are far from certain. Recipes for simple, everyday dishes were not written down in times past, as they would have been part of every cook’s and housewife’s repertoire. Recipes that do appear in pre-nineteenth-century cookery texts are frequently unclear, and many dishes referred to as “pancakes” appear to more closely resemble what we would now define as fritters (fried in deep fat), waffles (cooked between two heated plates), or omelets (a predominantly egg mixture). See fritters. There is also recipe confusion and overlap with hoe-cakes, johnnycakes, griddle cakes, flapjacks, slapjacks, and other similar articles. In some instances even today, “pancakes” turn out to be flatbreads, made from stiff dough that has been kneaded and rolled or pressed out.

The first written recipe in English for something unequivocally a pancake in form and method of cooking appears in the Good Huswife’s Handmaide for the Kitchin, published in 1588:

Take new thicke Creame a pinte, foure or fiue yolks of Egs, a good handfull of flower, and two or three spoonfuls of ale, strain them altogether into a faire platter, and season it with a good handfull of Sugar, a spooneful of Synamon, and a litle Ginger: then take a frying pan, and put in a litle peece of Butter, as big as your thombe, and when it is molten browne, cast it out of your pan, and with a ladle put to the further side of your pan some of your stuffe, and hold your pan aslope, so that your stuffe may run abroad ouer all the pan, as thin as may be: then set it to the fyre, and let the fyre be verie soft, and when the one side is baked, then turne the other, and bake them as dry as ye can without burning.

Leavening is not essential to pancake batter, but it does yield a lighter, fluffier result. Pancakes can be raised with eggs, yeast (including that in ale or beer), baking powder, or baking soda. See chemical leaveners; eggs; and yeast. Snow can also be used (see below), and stiffly beaten egg whites folded into the batter make an especially fine and light pancake. Leavening may also be achieved by allowing natural fermentation of the batter, which adds a characteristic sour taste to the pancake, as in traditional Russian blini made with buckwheat flour; bubbly-surfaced Ethiopian injera made from teff flour and water left to stand for several days; and the very similar Somalian lahoh, made from sorghum flour and water.

In its simplest form, a pancake can be made from flour and water only, but it would not be a delicious pancake. The choice of liquid used in the batter makes its own significant contribution to the style and flavor of the pancake. Milk in any of its myriad forms may be used, depending on preference and availability: skimmed milk serves the purposes of economy, and cream makes for a rich taste and texture. See cream and milk. Especially notable is buttermilk, which is acidic, and hence assists the leavening action of baking soda, if it is used. See buttermilk. Nondairy “milks” may also be used, as they characteristically are in Asia. Good examples include tiny rice flour and coconut milk pancakes called kanom krok in Thailand, and serabi in Indonesia. Virtually any liquid can be used, of course, and in the past, ale and wine were popular and common. The ale could also serve as the source of the yeast, which helped lighten the mixture.

For something so essentially simple, specific instructions nonetheless exist for making certain types of pancakes. Most often the pancake is turned to cook first on one side, then the other, but some thin pancakes, such as Moroccan beghrir, call for cooking one side only. When turning pancakes, the question frequently arises as to whether the pancake should be turned with a spatula or tossed. Although there is much sentiment and hype about tossing pancakes, tossing is not necessary, and it is fraught with risk to the pancake and to kitchen surfaces. However, tossing is a good party trick, and it is required at the traditional pancake-tossing races at Shrovetide.

In the Christian calendar, Shrove Tuesday is most closely associated with pancakes because it was traditionally the day to use up all eggs and milk before the long period of abstinence known as Lent. The most famous event of this day is a pancake race. Pancake racing is said to have begun in the distant past, when a woman making pancakes heard the church bell and, not wanting to waste her efforts, ran quickly to church, tossing her pancake as she went. Since 1950 the towns of Olney, England, and Liberal, Kansas, have held an International Pancake Race.

Pancakes lend themselves to serving in a wide range of situations. Their inherent simplicity means that they are most commonly associated with informal events such as family breakfasts, and they are favorites for campfire cooking. Glamorous versions are suitable for fine dinner parties and other entertainments. A prime example is the famous dessert Crêpes Suzette, whose origins are controversial. The chef Henri Charpentier claimed to have invented the dish in 1895 when he rescued a dessert from disaster in the royal kitchen of Edward, Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII). Charpentier renamed the dessert in honor of the prince’s female companion and served it to great acclaim—or so the story goes. Although called by different names, recipes for essentially the same dish appeared in the cookbook published in 1896 by Oscar Tschirky, maître d’hôtel of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York, and in the English edition of Auguste Escoffier’s Guide culinaire, published in 1903. Interestingly, neither recipe calls for a final stage of flambéeing, which is today considered intrinsic to the dish.

Pancakes in America

In America, the skill of pancake making certainly arrived with the earliest European settlers, and the national repertoire has been greatly expanded since then by migrant populations from around the world. The first authentic American cookery book, Amelia Simmons’s American Cookery, was published in 1796. It contains a pancake recipe that shows adaptation to local ingredients. Although the recipe specifies frying, it does not indicate how much fat to use, so the “Federal Pan Cake” may have been more like a fritter.

Take one quart of boulted rye flour, one quart of boulted Indian meal, mix it well, and stir it with a little salt into three pints milk, to the proper consistence of pancakes; fry in lard, and serve up warm.

An English cookbook widely reprinted in the young republic, A New System of Domestic Cookery by Maria Eliza Ketelby Rundell (1807), gives instructions for snow pancakes:

Is an excellent substitute for eggs, either in puddings or pancakes. Two large spoonfuls will supply the place of one egg, and the article it is used in will be equally good. This is an [sic] useful piece of information, especially as snow often falls at the season when eggs are dearest. Fresh small beer, or bottled malt liquors, likewise serve instead of eggs. The snow may be taken up from any clean spot before it is wanted, and will not lose its virtue, though the sooner it is used the better.

The quintessential modern American pancake is leavened with baking powder and served with maple syrup. See maple syrup. It is a staple at breakfasts in family kitchens and in diners across the country. In some regions it is known as a hotcake. The phrase “hot cakes” appears to be an American invention, and first appeared in 1683 in a letter from William Penn, governor of Pennsylvania, to the “Committee of the Free Society of Traders of that province residing in London.” The “hot cakes” to which he refers, however, are clearly not pancakes in the accepted sense of the word today. Penn is writing of the food of the Native Americans when he says “with hot cakes of new Corn, both Wheat and Beans, which they make up in square form, in the leaves of the Stem, and bake them in the Ashes.” See native american. Similar confusion exists with other references to hot cakes or hotcakes over the next few centuries—it is impossible to know for certain if they were fritter-like or flatbread-like.

The phrase “selling (or “going off like”) hotcakes” also first appeared in an American publication, in 1839. In The Adventures of Harry Franco, a novel about the great financial panic of 1837, Charles Briggs writes: “‘You had better buy ’em, Colonel,’ said Mr. Lummucks, ‘they will sell like hot cakes.’”

The modern concept of a hotcake as a pancake could not have appeared before the development and widespread use of chemical leaveners, which did not occur until the late eighteenth century. But once commercial baking powder became available in the mid-nineteenth century, powder-risen pancakes rapidly became an American favorite. An English reporter described his experience of an American breakfast in an article titled “Hotel Life in New York,” in the 27 December 1860 issue of the London Times. He notes that “breakfast may be obtained from half-past 6 till 11, and on a scale of which even our neighbours north of the Tweed [i.e., in Scotland] have no conception.” The intrepid reporter tackles steak, potatoes, and fried oysters, after which the waiter prevails upon him to try something more:

…a little broiled fowl, or an omelet? Well, you will have some hot cakes? Hot cakes are an American institution (every custom, I should remark, is termed an “institution” in America).

These hot cakes resemble crumpets, and are generally served in a pyramidal form, a large cake forming the base, and the small one the apex of the pile. A little butter is placed between each cake, and syrup (refined molasses) poured over the whole.

See also chestnuts and tapioca.

pandanus, though largely unknown to cooks and chefs in the West, is an important flavoring and coloring ingredient in the sweets repertoire of South and Southeast Asia, from India to the Philippines.

Pandanus is a genus of flowering trees and shrubs that includes over 600 species of tropical and subtropical plants native to Asia. Pandanus amarillifolius (formerly Pandanus odoratissimus), usually called “pandan” or “screwpine” in English, is the species that provides cooks with pandan leaves (bai toei in Thai, daun pandan in Malay, pandan in Tagalog, sleuk toey in Khmer, la dura in Vietnamese, rampe in Sinhala, and su mwei ywe in Burmese). The leaves give a delicate scent and flavor reminiscent of basmati rice, with hints of rosewater and vanilla. They also lend an attractive light green tint.

The male flowers of several species of pandanus are the source of “screwpine essence,” an aromatic, pale orange liquid used in South Asian cooking to flavor sweets and drinks. See extracts and flavorings.

Pandan leaves look a little like narrow gladiolus or daylily leaves: bright green, long, flat, and pointed. They are available fresh in Asia, Hawaii, and Australia, and occasionally in colder-climate regions. In North America and Europe, however, cooks more commonly have access only to frozen pandan, which also works well. To use pandanus, tie several leaves in a knot and then simmer in water, milk, or coconut milk until they have released their aroma and green color; the knot enables them to be lifted out easily when the dish has cooked.

In Malaysia, Indonesia, and India, pandan leaves are most often cooked with rice to add a light green tint and impart an aromatic flowery flavor; they also perfume coconut-milk-based desserts in Southeast Asia. These days in Asia, a number of factory-made ingredients, such as tapioca balls, fine rice noodles, and rice-flour-based sweetmeats are dyed green with vegetable dyes to evoke pandan.

See also india; philippines; south asia; and southeast asia.

panning is the process for making sugared almonds, comfits, dragées, jelly beans, M&M’s, and numerous other items in which nuts, spices, and pieces of candied fruit, fruit paste, sugar paste, or chocolate are coated with sugar shells. See comfit; fruit pastes; and jelly beans. The principles behind it have been known since at least the early medieval period in the Middle East.

Confectioners differentiate between hard panning—using sugar syrup in a slow process to make smooth, hard-centered items—and soft panning, which uses sugar and glucose syrup in a rapid process to make irregularly shaped candies with a soft bite. Chocolate can also be used as a coating in panning, as in chocolate-covered raisins.

Simple in principle, the panning process is, in fact, complex. For hard panning, first ingredients for the centers are prepared by shaping and drying with gentle heat in a warm room; nuts also require sealing with gum arabic and flour. These steps are important, as even tiny amounts of moisture or oil can discolor the surface of finished items.

Next, the centers are placed in large pans that are mounted at an angle. These revolve, tumbling the contents, and successive “charges” of syrup of relatively low concentration are added, a process known as “wetting.” Air, supplied to the pans through nozzles, dries each charge in a thin layer before a subsequent one is added. This, too, is important, as inadequately dried sugar gives the finished sweets a grayish cast. Air temperature varies according to the type of center: for instance, cold air is recommended for sugared almonds, warm air (104°F [40°C]) for nonpareils. Other ingredients such as perfume or color can be added to the syrup and dustings of starch help to build up the coats and absorb syrup. This “engrossing” is repeated until the coating achieves the desired thickness. A final panning with beeswax, carnauba, or paraffin wax yields a polished surface. The small silver balls used for cake decoration are made by panning with silver dust or leaf in the final stages of production. See leaf, gold and silver.

Panning is a skilled process in which subtleties of speed and temperature (for both pans and airflow) and concentration of the syrup are crucial. It is also time consuming: engrossing is slow and can be intermittent; soft panned items need periods of drying on trays both during the process and afterward.

Illustrations in early confectionery books show panning done by hand. They imply that confectioners vigorously shook the sweets in shallow, bowl-like balancing pans suspended over burning coals, thereby exaggerating a process that actually requires gentle heat and thorough stirring. Careful attention to syrup concentration produces different surface textures, and drying between coats is essential for good results. The technique of adding subsequent coats explains one of the great mysteries of British childhoods: how the enormous sweets known as gobstoppers can change color as they are sucked.

pans come in a vast assortment of shapes, sizes, and materials. The correct pan is as essential to many cakes as the batter itself. For example, French cake pans have sloping sides that make possible an even coating of melted fondant icing for classic gâteaux. English cake pans with straight sides are deeper than American ones so as to accommodate heavier fruit-laden batters; shallow American pans are designed for stacked layer cakes that are tall with straight sides. Even tart pans are different: a French tart pan is made of metal with a decorative, fluted edge and a removable base for easy unmolding, whereas an American pie plate has sloping sides for ease of serving the pie directly from it. The oval, deep English pie dish is unknown in either country.

Today’s most favored baking pans are made of heavy-gauge aluminum or Pyrex (tempered glass); others are available with a nonstick finish, or are made from cast iron or silicone. Because Pyrex transmits heat very efficiently, glass pans require a cooler oven temperature, so bakers are advised to set their ovens 25°F (–4°C) lower than when using other pans. Cast iron transmits heat inefficiently, so some recipes suggest preheating these pans before filling them with cake batter or dough. Silicone pans are appreciated for their flexibility and nonstick property, which eliminates the need for greasing, a necessary step for most baked goods to ensure their release from the pan. Paper cake pans are also on the market, although they are mainly for professional bakers.

Round pans are suited for baking single- or multilayered cakes, and elongated loaf pans accommodate quick breads. Standard rectangular pans range in size from 5 × 8 inches to 18 × 24 inches and are useful for bar cookies and brownies. See bar cookies and brownies. Muffin and cupcake pans are made of individual cups joined together in a rectangular form. Historically, muffin tins were made from individual cups soldered together into three or four rows. Today, they come in many different patterns, ranging from miniature to large, shallow indentations for baking crusty muffin tops. Some pans have sculpted patterns in the bottom; when inverted for serving, the cakes display a decorative top. See cupcakes and muffins.

Cookie sheets, jellyroll pans, and sheet-cake pans are generally interchangeable. The most important feature is a low lip edge, as a deep pan would present problems in removing drop, rolled, or pressed cookies. See drop cookies; pressed cookies; and rolled cookies. Many bakers favor cookie sheets with only a small, curved lip on one narrow side that enables the baker to pick up the sheet; it is very easy to lift or slide cookies from the three lipless sides. Shallow, 1-inch deep rectangular jellyroll pans are usually 10 × 15 inches. Like cookie sheets, they are frequently lined with parchment paper so that the baked goods will not stick.

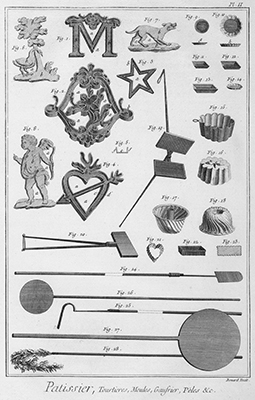

This photograph of various pans, plates, sheets, and molds for baking appeared in a 1912 Cornell University Household Economics and Management bulletin on “Choice and Care of Utensils.” cornell university library

Pie pans, also called “tins” or “plates,” are generally made of Pyrex, aluminum, coated steel, or stoneware. Standard pans are 1 ½ inches deep; “deep dish” pans, at 2 to 2 ½ inches in depth, can accommodate more filling. Pie pans are available in sizes ranging from 6 inches to 12 inches in diameter, the most popular being 9 and 10 inch. Some (particularly those made of Pyrex or stoneware) have fluted edges to facilitate making a decorative finish to the crust. See pie. Tiny tartlet molds, including fluted and unfluted barquette tins, are used for miniature confections; various sizes of round, shallow pans, usually with fluted sides, are specifically designed for quiches and tarts.

Round torte or spring-form pans, with removable bottoms, are usually manufactured from sheet aluminum. See torte. This fairly flexible material permits the opening and closing of the pan’s overlapping sides, which are secured by the use of spring clasps. These pans, ranging from 5 to 14 inches in diameter, can be 3 to 7 inches deep for home baking; commercial pans may be deeper still. After the torte is baked and cooled, the sides are released, opened, and removed. Sometimes the torte is easier to slice and serve from the pan bottom itself, particularly when it is large or fragile, but the baked layer may also be removed to a cake plate for slicing and serving.

Special-purpose baking pans include aluminum angel food cake pans and Turks’ head or turban molds with a removable bottom and spiral patterning on the sides; both types have a central tube that allows the heat to penetrate the batter more efficiently and ensure that the cake will cook evenly. Similar pans, without a removable bottom and generally made from cast iron, aluminum, or silicone, are called Bundt pans, after the coffee cake–style Bundt cake that unmolds with a decorative pattern. See angel food cake and gugelhupf.

See also breads, sweet; cake; frisbie pie tins; and layer cake.

Paris, the capital of France, is one of the world’s great gastronomic centers. Its proximity to the famed butter of Normandy and to high-quality French flour gave the city a natural advantage in pastry making that continues to the current day. However, its fame owes at least as much to the systemized culinary techniques that its best practitioners spread internationally.

From Antiquity to Renaissance

Paris’s fertile surroundings allowed for the successful cultivation of many fruits from an early date. The Roman emperor Julian’s fourth-century description of the native Parisii tribe records that they were even growing figs by covering the trees to protect them from the harsh winter. Mesnagier de Paris (ca. 1393) provides advice to a Parisian housewife on how to cultivate violets, mint, raspberries, currants, seedless grapes, cherries, and plums. Pears were so ubiquitous that the French word poire could be used as a synonym for dessert. Apples were nearly as prevalent and remain a staple.

By the Mesnagier’s era, the city had become a thriving international metropolis with a wholesale market to match. Contact with the East during the Crusades brought exotic sugar and spices in increasing quantities. Other products came from regions across the kingdom and beyond.

Having survived Roman occupation, Viking invasions, and years of relative obscurity, Paris had become the capital of West Francia with the accession of Hugh Capet to the throne in 987. But from the twelfth century the city’s expansion accelerated phenomenally. Its population exploded from an estimated 3,000 residents in 1100 to around 200,000 by 1300. A central, wholesale market at Les Halles was established by 1137 and quickly expanded, especially after the construction of permanent buildings in the 1180s. By the Mesnagier’s era, one could buy waffles, sugar in myriad forms, dragées, and other sweets from an impressive list of expert vendors. The core of the city began to take on recognizable form with a highly legislated food market at its physical and metaphorical epicenter.

The almond- and butter-rich gâteau du roi, which is still made throughout northern France for Epiphany, hearkens back to this era. This tradition remains so popular in Paris that many patissiers set up outdoor stands exclusively to sell this cake during the season. See twelfth night cake.

By the sixteenth century the city excelled at elaborate sugar sculptures and pastries for lavish entertainments, such as the multisensory magnificences organized by Catherine de Médici for the Polish ambassadors in 1573. See médici, catherine de and sugar sculpture. These effete celebrations differed little from analogously regal events held elsewhere in Northern Europe. However, they are remarkable because they occurred not quite a year after one of the city’s bloodiest episodes, the crown-endorsed St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, which left thousands of Protestants dead. This was but one battle in nine gruesome Wars of Religion that rippled through France from 1562 until 1594. Nevertheless, in the midst of this tumult, the Venetian ambassador to France raved about the astounding array of food products available in Paris and lavished praise on its patissiers and caterers.

Ancien Régime

Paris and its cuisine grew increasingly sophisticated through the seventeenth century. Paradoxically, however, the city did not develop a distinctive gastronomic style until the court definitively left it.

Louis XIV moved the court into full-time residence at Versailles in 1682. Paris then became the center of French counterculture. The city’s first extant café, Le Procope, opened just four years later to serve the newly imported beverage coffee to a clientele featuring freethinkers. The institution of the café has epitomized Paris ever since. See café.

The Procope’s Italian-born founder gained as much renown for his ices as for his coffee. Although glacés had been served privately to elite Parisians a century earlier, they henceforth became a favored treat for public consumption at fashionable venues in the Palais Royal and on the Boulevard des Italiens, such as Tortoni’s.

The first book devoted solely to ices was written and published in Paris by M. Emy in 1768. This volume features ice creams with an egg-custard base, which are not dissimilar to those now produced by Paris’s famed glacier Berthillon (founded 1954). See emy, m. and ice cream.

A craze for thick, slightly bitter hot chocolate, which continues to be popular, matched that for glacés. Both emerged from the application of Enlightenment logic to colonial products. More broadly, they contributed to Paris’s emergence in the eighteenth century as Europe’s preeminent source of luxury goods from fashion to furnishings.

Pastry techniques made the most significant and resonant advances. Parisian manuals such as Augustin Roux’s Dictionnaire domestique portatif (1762–1764) demonstrate that even before Paris spawned the world’s first restaurant, it had developed and refined the pastry techniques that continue to underpin the French tradition.

Many of the most renowned practitioners had foreign origins. Nicolas Stohrer, who in 1730 founded Paris’s oldest extant patisserie, is presumed to be from the area of Wissembourg where he apprenticed. He is credited for bringing the baba to Paris. See stohrer, nicolas. Other new forms of biscuits, macarons, gâteaux, madeleines, and brioches that became similarly associated with the city also originated elsewhere. Paris was the hub where ideas were exchanged even as techniques codified.

Although Marie Antoinette never said, “Let them eat cake,” on the eve of the French Revolution of 1789, this apocryphal phrase succinctly conveys the fact that while many struggled to afford bread, wealthy Parisians of the ancien régime were spoiled in their choice of fine pastries.

Post-Revolution to Belle Époque

In the post-Revolutionary era, the production and marketing of sweets (as was the case for many luxury trades) carried on strangely unaffected and simultaneously transformed. The newly rich enjoyed spending publicly with “see and be seen” bravura. This resulted in more glamorously appointed patisseries, cafés, and shops as well as inventiveness fueled by the need to captivate a fickle audience. Alexandre-Balthazar-Laurent Grimod de la Reynière (1858–1837) documented this phenomenon in the world’s first food journal, which debuted in Paris in 1803.

Marie-Antoine (Antonin) Carême (1784–1833) was that generation’s most celebrated patissier and chef. See carême, marie-antoine. Although he worked privately, he created dazzling, architectonic pièces montées for public balls. More important, he “doubled” (by his own estimation) the range of French pastries and techniques and disseminated them through books that garnered international attention. Although his work incorporated ideas taken from stints in London and Vienna, he extolled his native Paris as the globe’s gastronomic capital.

Carême’s Pâtissier royal parisien appeared the same year as Napoléon Bonaparte’s ultimate defeat. Although French military dominance ended in 1815, Paris’s reputation as preeminent in European gastronomy ascended ever higher. Carême’s protégés Jules Gouffé (1807–1877) and Auguste Escoffier (1846–1935) continued this trend into the twentieth century. See escoffier, georges auguste.

The city itself also grew exponentially, doubling its population from 700,000 in 1815 to a whopping 1.7 million in 1861 and an all-time high of 2.9 million on the eve of World War I. New immigrants, such as Viennese-born August Zang, who in Paris in the late 1830s produced the first recognizably flaky croissant, added their traditions to the mix. See croissant. However, regional and national differences got smoothed into a system no less regimented than the military.

These developments continued largely unchecked until World War I, with the exception of the infamous Siege of Paris of 1870 and the ensuing chaos of the Paris Commune. Nevertheless, Ladurée bears witness to the rapidity with which many businesses oddly thrived upon these traumatic events. A fire during the 1871 Commune burned down the original bakery of 1862. This allowed for the construction of a luxurious tearoom designed to appeal to women, whose purchasing power had already been realized by newfangled department stores such as Le Bon Marché (founded in 1852).

As steamboats, railways, and eventually automobiles brought increasing numbers of visitors to the City of Lights, its spectacle crescendoed to a feverish pitch. Glittering events and personalities often received a commemorative dessert. Many remain classics today. Escoffier invented the Poire Belle Hélène in 1864 for Offenbach’s operetta La belle Hélène; and even the Paris-Brest bicycle race that started in 1910 received its own pastry in the shape of a wheel.

World War I to the Present

World War I took an especially hard toll on Paris, which was closer to the battle lines than any other major city. Sugar and coal were the first goods to be rationed; fancy pastries were entirely banned. As a supply hub, the city became adept at prefabricating food in large quantities. Prospere Montagné (1865–1945) learned to organize approximately 16,000 bread rations per sitting that could be reheated on the battlefield. His techniques soon found their way into civilian production after the war, alongside a vogue for American jazz, cocktails, and refrigerators.

Nevertheless, a conservative backlash fought to preserve traditional craftsmanship from architecture to gastronomy. Created under this impulse in 1929, the Meilleurs Ouvriers de France (best workers of France, known as MOFs), which includes categories for chocolatiers and patissiers, guard classical techniques through rigorous and extensive training.

When Paris capitulated to the Nazis in June 1940, huge swaths of the population simply fled. The city was already in rough shape economically. Yet, in spite of rationing, pastries and other luxury goods remained available to collaborators as well as to black-market purchasers.

However, German occupation cost Paris its hitherto unassailable self-assurance, which negatively affected its food. By the 1970s American-style supermarkets sold packaged sweets and rubbery croissants throughout the city, and even many specialty patissiers increasingly cut corners.

At the top of the market, Paris gradually reestablished itself as a world-class capital for luxury goods, including sweets. Parisian chocolate, exemplified by the masterful sculptures of Patrick Roger, is as stunning as it is intense. Parisian sophisticates ignited the recent worldwide craze for macarons as devotees of rivals Ladurée and Pierre Hermé sparked heated debates on the subject. See hermé, pierre. Competitions to determine the capital’s best examples of classics such as croissants, éclairs, and the Paris-Brest have recently mushroomed. Raised public awareness has been met with a proliferation of high-end patisseries. That the world’s first dessert-only restaurant, Dessance (serving three-course meals of sweets), opened in Paris in early 2014 bears witness to the city’s ongoing ability to innovate even as it upholds classical standards.

See also baba au rhum; france; macarons; madeleine; pastry, choux; and pastry, puff.

Passover, the eight-day festival of freedom celebrating the Exodus from Egypt, is probably the foremost Jewish holiday today. It is also one of the world’s oldest continually observed festivals. No products made from regular flour and no leavened food (more precisely, no fermented foods) can be eaten at Passover. This practice is based on a passage from Exodus 12:15, “For seven days you are to eat bread made without yeast. On the first day remove the yeast from your houses, for whoever eats anything with yeast in it from the first day through the seventh must be cut off from Israel.” Pesach in Hebrew means “passing by” or “passing over”; the holiday was called Passover because God passed over the Jewish houses while slaying the firstborn of Egypt. During most Jewish ceremonial meals throughout the year, two loaves of the sweet, enriched bread known as challah are served, but on Passover three matzahs are placed on the table instead. Matzah, the unleavened and quickly baked bread prepared for Passover, reminds contemporary celebrants that the Jews fleeing Egypt had no time to leaven their bread or to bake it properly.

Today, the eight-day festival maintains its family character, beginning with the traditional Seder meal at home. The central object of every table is the Seder plate arranged with symbolic foods, including haroset, a sweet fruit and nut blend symbolizing the mortar that Jews used to build the ancient Egyptian pyramids or buildings (it is not clear that it was the pyramids). While the Ashkenazic mixture typically contains apples and walnuts, the Middle Eastern and Sephardic versions often include dates, but other ingredients vary according to the country and sometimes even the city of origin. Besides these symbolic foods, Passover recipes themselves have evolved over the years, reflecting the foods of the countries to which Jews immigrated. To compensate for the absence of flour demanded by the biblical rule, Jews throughout the world have created all kinds of baked goods, such as soaked matzah and, later, matzah cake meal made from carefully watched flour, meaning that it has not touched any other flour or been near anything fermented during the year, ensuring that it is acceptable for Passover.

Some Passover favorites include flourless tortes using egg whites beaten until stiff, ground nuts, sugar, and egg yolks; sponge cakes containing matzah meal or potato flour; macaroons made from almonds or coconuts; Schaumtorte, a large meringue filled with strawberries; and chremslach or krimsel, fritters made from dried fruit, nuts, and spices, and sometimes stuffed with apples or jam. Beet or carrot eingemachts (preserves) were traditionally popular in Lithuania and Russia. Jews from Morocco make preserved fruits to eat as a sweet at Passover, such as candied eggplant and candied oranges. Jews from Salonika ate candied almonds. In the United States today, Americans enjoy fruit-flavored jelly slices or jelly rings coated with chocolate. Increasingly popular desserts are made from matzah coated with chocolate or a toffee-like, buttery, crunchy topping. And in Israeli homes, one can find every imaginable Passover sweet known to mankind.

See also judaism.

pastel de nata (pl. pasteís de nata), perhaps the most ubiquitous of all Portuguese sweets, is an egg custard tart. The pastel de nata can be found in every pastry shop in continental Portugal as well as on Madeira and the Azores Islands, where the tarts are commonly referred to as queijadas de nata.

The pastel de nata originated sometime prior to the seventeenth century in the Santa Maria de Belém quarter of Lisbon. Pastry production provided religious orders with supplemental income, and the monks of the Monastery of the Hieronymites first created these tarts to help offset monastery expenses. The tarts were made from yolks left over from eggs whose whites were used to starch clothing and purify wines. See egg yolk sweets. Following the Liberal Revolution of 1820, Portuguese religious orders were closed; as a means of survival, the Hieronymite monks contracted with a nearby bakery to produce and sell their tarts. These particular pastries became known as Pasteís de Belém, and the monks’ original recipe was patented and registered. These tarts continue to be made and sold at the Antiga Confeitaria de Belém, Lda., their recipe still a closely guarded secret.

Though regional variations exist, the pastel de nata is commonly made of puff pastry, egg yolks, sugar, and flour. See pastry, puff. Some recipes also call for lemon peel, cream, vanilla, and milk. Whatever the combination of ingredients, a pastel de nata hot from the oven—often sprinkled with cinnamon and powdered sugar—is a divine tribute to Hieronymite ingenuity.

See also portugal.

pastila is an ethereal fruit confection that is one of Russia’s oldest sweets, likely dating back to the fourteenth century. It originated as a way to preserve the apple harvest by cooking tart, pectin-rich apples until soft, then sieving them into a purée dried slowly in the oven. (The name derives from the Latin pastillus, meaning a “small loaf.”) Two Russian towns lay claim to pastila: Kolomna, near Moscow, where the confection was probably first produced, and Belyov, near Tula, where the recipe was perfected. The secret to excellent pastila is the addition of air through copious beating and through egg whites, which turn the dense apple paste into a light, airy mass. After whipping the apple purée until light, egg whites beaten stiff with a little sugar are folded in (the original sweetener was honey). This mixture is spread in a thin layer on a baking sheet to dry for several hours at low heat in the oven. The Belyov version calls for reserving a little of the beaten apple mixture to spread between layers of the baked pastila. The stacked confection is then returned to the oven to dry a little more, resulting in a surprisingly moist confection that is sweet yet tart, less gelatinous than marshmallow, and softer than meringue. Although apples are traditional, pastila can also be made from berries and even hops, a version touted in the nineteenth century as a hangover cure.

During the Soviet era, the art of making pastila was largely lost, but now it is experiencing a revival. A museum devoted to pastila opened in Kolomna in 2009, and in Belyov a campaign is under way to restore the gravesite of Amvrosy Prokhorov, the nineteenth-century merchant whose layered pastila gained renown throughout Russia and Europe.

See also Russia and guriev kasha.

pastillage is a malleable sweet dough made of powdered sugar, water, binding agents such as gum tragacanth or gelatin, and acid (vinegar or cream of tartar) that is used in making edible decorations.

In recipes and illustrations dating back to the seventeenth century, pastillage is presented as part of the confectioner’s arsenal to impress the British and French nobility. Only the very rich could afford the expense of processed and pulverized white sugar and the artisanal expertise of dedicated pastry chefs.

The dough can be tinted with food colors, but historically it has remained a pristine white. After kneading, the dough is rolled thin and cut into shapes with a sharp knife following a paper template or with cutters. It can also be pressed into cavity molds and released. The pieces are laid flat to dry, or draped along curved objects until they hold their shape. The dough starts to crust immediately and fully hardens within 24 hours. Once dry, any rough edges are often sanded, and separate pieces are attached to one another using royal icing or sugar cooked to 320°F (160°C). See icing and stages of sugar syrup. In contemporary show work, an airbrush is often used to lend color and texture to the completed piece. The final results are sturdy and can be used as candy dishes, ornamental supports in wedding cakes, and architectural structures. See wedding cake. Today, pastillage is mostly used in competition work as a pièce montée for buffets.

Pastillage is not delicate enough for forming realistic sugar flowers or sculpted figurines, which are typically made of derivatives called sugar paste (in the United Kingdom and South America) or gum paste (in the United States). Nor is it used for icing cakes, for which a more emollient version exists by the names of sugar paste (United Kingdom, South Africa, and Australia) or rolled fondant (United States). See fondant.

See also cake decorating; carême, marie-antoine; competitions; and tragacanth.

pastry, choux, or cream puff pastry, when baked or fried yields a crisp exterior surrounding a characteristic hollow center, ready to be filled. Made from a paste of butter, water (or milk), flour, and eggs, this workhorse in both the savory and sweet sides of the kitchen relies for its leavening on eggs and the steam created by the water in the dough. Notable for being twice cooked, once on the stovetop and then baked or fried, versions of this dough have been around at least since Roman times. Choux pastry was widely used in the Renaissance; Bartolomeo Scappi includes a recipe for it in his 1570 Opera, using the dough to make fritters. See fritters. In pre-Revolutionary France this pastry dough was known as pâte royale; Republican France renamed it pâte à choux, since it was mainly used to make “petits choux” or cream puffs, which were seen to resemble choux (cabbages).

Whatever it is called, this dough is versatile. On the savory side, it is mixed with cheese to make gougère and with mashed potatoes to make pommes dauphines, which are fried. The dough is also widely used to create sweet fritters, whether Spanish churros or buñuelos de viento, Neapolitan zeppole di San Giuseppe, French croustillons (also known as pets de nonne), or America’s “French” crullers. See fried dough. In the French pastry repertoire, baked versions of the dough result in cream puffs, éclairs, miniature swan-shaped pastries, Gâteau St. Honoré, and Paris-Brest, among other configurations. For these particular sweets, the dough is variously shaped, baked, and finally filled.

pastry, puff, is a dough made by layering a flour–water paste with butter, resulting in very thin layers that “puff” up when baked into delicate layers or leaves; both the French pâte feuilletée and Italian pasta sfogliata derive from the word “leaf.” Bakers have figured out two ways to do this. In a technique documented in medieval Arab sources, dough smeared with liquid fat is shaped into a cylinder and then rolled thin. This technique was certainly used in medieval and early modern Spain and is still used to make Neapolitan sfogliatelle. The origin of the French technique, in which the flour–water paste is repeatedly folded around solid butter, rolled out, and refolded, is much more controversial. According to one story, a French pastry cook’s apprentice named Claudius Gele invented puff pastry in 1645, inspired by the diet of flour, butter, and water that his sick father was ordered to follow. An even more improbable tale ascribes that same discovery to the baroque French painter Claude Lorrain. Whether this technique was invented independently in France or developed out of the Arabic approach is difficult to verify. There is mention of a gâteau feuillé as early as 1311, although what this pastry actually was is pure conjecture.

Whatever its origins, the idea of layering or laminating fat, most commonly butter, into a dough of flour and water certainly gained favor in Europe, from Spain to France to Italy and beyond, and has become a staple of the pastry kitchen throughout the region. Puff pastry is considered the consummate example of the pastry maker’s art, requiring precision, patience, and time. See laminated doughs.

Ever since La Varenne’s Pastissier françois (1653) included the first printed recipe for pâte feuilletée, the basic method for making the dough has remained largely the same. In general, the weight of flour and fat is equal. The flour is mixed with water and often a small amount of fat into a smooth, elastic dough called the détrempe (from the French word tremper, meaning “to dip or soak,” alluding to the process of using one’s fingers or hand to combine the dough and water). This dough is set aside to rest under refrigeration so that it will be easy to roll during its multiple layering, known as the lamination process. Then the laminating fat is worked until it is malleable but not greasy and shaped into a thin sheet, sized to fit within the détrempe when it is rolled out.

Risolles aux poires—pear jam enclosed in light envelopes of puff pastry—are a specialty of France’s Savoie and Haute-Savoie regions. photograph by marc le prince

The process of rolling out the dough to enclose the butter, known as beurrage, may be done in one of four ways. In the first method, the dough is rolled into a symmetrical four-petaled clover shape with the center left a bit thicker than the four “petals.” The butter is then placed into the center of this “flower” and the petals are folded over the center to enclose it. The second method involves rolling the détrempe into a rectangle three times as long as it is wide. The dough is visually divided into thirds, with the butter placed on the middle third. The unbuttered dough to the left and right of the buttered third is then folded over the butter to enclose it. In the third method, the dough is rolled out to a rectangle, and one half of it is covered with the butter layer. The unbuttered half is then folded over the buttered half, and the seams are sealed. The final method, called pâte feuilletée renversée (or inversée; reverse or inverse puff pastry), is the opposite of the three previous methods. It calls for placing the butter packet on the outside of the dough to enclose it.

No matter which method is used, the dough is then rolled out with long strokes, using even pressure to ensure that the butter and dough are flattened to equal thicknesses. This rolling and folding process is known in French as the tourage. The resulting rectangle is then folded in one of two ways. A simple fold has three dough layers enclosing two layers of butter; the process of rolling and folding is repeated a total of six times. The four-layered book fold also encloses two layers of butter, but the rolling and folding are repeated only four times. In both cases, the dough is chilled well between each “turn” to allow the butter to solidify and the gluten in the dough to relax.

“Rough” or “quick” puff paste, arguably a variant of flaky pie pastry, involves a simpler process in which butter, cold but still malleable, is cut into large pieces and mixed directly with the flour, ice water, and a bit of salt. The resulting dough is then patted into a rectangle on a floured surface with firm, steady strokes of the rolling pin before being rolled out, folded, and chilled. This process is repeated three times, with the dough refrigerated after each rolling. The finished dough yields less distinct individuation of layers and only a moderate amount of inflation during baking.

Puff pastry has many uses, both savory and sweet. It can be rolled around a filling, as in Beef Wellington or salmon coulibiac, or form the base for numerous tarts and tartlets. Perhaps the best-known use of puff pastry is in the classic mille-feuille (thousand-layered pastry) or Napoleon, for which the dough is rolled into rectangles and, after baking, cut and layered with pastry cream; the top layer is traditionally coated with fondant. See fondant. The pastry shell known as vol-au-vent, containing savory and often creamy fillings, is another common use for the dough. Puff pastry also forms the basis for smaller pastries such as chaussons (turnovers usually filled with cooked fruit), sacristains (rectangular strips of dough encrusted with sugar and almonds), allumettes (“matchsticks”—thin strips of dough often coated with fondant), and palmiers (palm-leaf shaped cookies, sugar-coated and caramelized).

When properly made, puff pastry is light and airy, boasting impossibly thin, fragile, melt-in-the mouth layers, a miracle of pastry engineering based on a mere handful of ingredients.

See also france; pastry, choux; and pie dough.

A pastry chef is the person responsible for designing the dessert menu in a restaurant, hotel, or pastry shop. The pastry chef typically works in consultation with the chef in charge of the savory side of the kitchen to ensure harmony in the meal from start to finish. Depending on the size of the establishment, pastry chefs might work on their own or with a team, which can vary in size from one other person to dozens of employees in a hotel. When a restaurant cannot afford to employ a full-time pastry chef, one might be asked to consult and create a dessert menu that a more junior cook will execute, or the chef-owner might take on that responsibility. Because not all customers order desserts, whether for dietary or financial reasons, the pastry kitchen is often an area of the restaurant where budgets are trimmed.

In this engraving from around 1690, called “Costume for a Pastry Cook,” a pastry chef is fantastically outfitted in the tools and creations of his trade. It was published by Gerard Valck, a Dutchman better known for his cartographic publications. private collection / the stapleton collection / bridgeman images

Many restaurants, including high-volume operations, do not employ pastry chefs but instead rely on manufactured desserts. Some of these might be custom-made for a specific restaurant, or the establishment can choose from a large selection of standard offerings. Some independent restaurants have neither the need nor the budget for a pastry chef; these also tend to rely on consulting pastry chefs, who create a dessert menu that can be executed by an existing employee. The consultants might come in several times a year to give the menu seasonal tweaks or make other adjustments. Fine-dining restaurants, especially those with a prix fixe tasting menu that includes desserts, are more likely to have a named pastry chef whose reputation serves to attract diners.

Restaurant pastry chefs rarely create large-scale desserts, other than the occasional wedding or birthday cake and, depending on trends, full pies or cakes from which slices are served to diners. They focus instead on plated desserts, which are created and served in individual portions. See plated desserts. These desserts typically comprise multiple components, such as a cake, tart, or similar item with a smooth filling or topping like custard or pastry cream; an ice cream, sorbet, or other frozen or iced element; and a textural component like meringue, caramel shards, or crumbly freeze-dried fruit bits. In hotels, pastry chefs can handle large banquets, parties, and conferences and thus often create showpieces for display, along with a large variety of desserts that can be kept at room temperature on a buffet table for a couple of hours and serve hundreds of people, something that is harder to achieve with frozen or plated desserts. Verrines—layered desserts served in glasses or cups—are popular in high-production settings. See verrine.

Pastry chefs in pastry shops handle a different type of high-output production, focusing often on items such as macarons, éclairs, and other individually sized pastries, along with cakes and tarts one might purchase for a dinner party, and viennoiseries such as kouign-amann and croissants. In order to stand out in an increasingly competitive marketplace, many pastry chefs develop specialties that can attract media and consumer attention.

The first celebrity pastry chef is also one of the most celebrated figures of modern cookery. Marie-Antoine Carême was born in Paris in 1783 and died in 1833 after authoring such books as Le Pâtissier royal parisien, Le Pâtissier pittoresque, and L’art de la cuisine française au 19-ème siècle. See carême, marie-antoine. Sculptural showpieces, a Carême trademark, are still a skill pastry chefs must master in competitions (even if restaurant pastry chefs, other than those in hotels, rarely find time to compete). See competitions and sugar sculpture. Today, some modernist pastry techniques have evolved from classic French ones. In particular, Albert Adrià of elBulli in Spain developed a large range of new practices, such as making spherified purées and edible landscapes. Other technologies, including the use of liquid nitrogen, have allowed for ice cream made à la minute or containing more alcohol than is possible with a normal freezer. See sugar in experimental cuisine. Pastry chefs have taken more liberties with their menus to reflect seasonality and their own flavor preferences, resulting in a greater diversity of desserts. However, despite these innovations, typical French techniques and dessert components, from doughs to pastry creams to cakes, remain the foundation of dessert menus and training curricula around the world.

Because pastry chefs often toil in a windowless basement, particularly in large cities, once they reach a certain level of fame working for someone else, their careers generally become less linear than those of savory chefs. For a time some opened dessert-centric restaurants, but that trend seems to have peaked in the mid-2000s. Pastry chefs who can capitalize on visibility from their work in high-profile restaurants can move into product development, consulting, or the creation of more traditional pastry or ice cream shops. They can also often parlay their fame into cookbook contracts and television appearances.

As pastry chefs have gained more attention from media and consumers throughout the United States, they have been asking for more official recognition in the form of awards, like those bestowed by the James Beard Foundation or Food & Wine magazine. As of 2014, however, the James Beard Foundation still only granted one award in this area, for best pastry chef in the country.

See also croissant; dessert; desserts, chilled; desserts, frozen; ice cream makers; macarons; and pastry, puff.

pastry schools in the United States assumed their current form during the second half of the twentieth century as the result of a unique confluence of governmental and cultural factors. Today, bakers and pastry chefs commonly learn their craft through on-the-job training, apprenticeships, and culinary schools. Although certificates and degrees are not required to work in the industry, a formal culinary education has become the preferred method for jump-starting or advancing a culinary career.

Early cooking schools catered primarily to upper-class women who studied for social and domestic prowess, as opposed to job preparation. In England, Edward Kidder operated one of the first cooking schools to include mostly baked goods during the early to mid-1700s. By the late 1700s, Elizabeth Goodfellow in Philadelphia had established a similar program in her city bakeshop for well-heeled ladies. Eliza Leslie, the heralded author of books on cookery and etiquette in the 1800s, was one of Goodfellow’s more accomplished pupils. In the larger American port cities, cooking schools were not uncommon by the nineteenth century. Already in the mid-1800s, French chef Pierre Blot had established the New York Cooking Academy, which offered separate classes for upper-class women, domestic servants, and professional cooks. In London in the late 1800s, Agnes Marshall, the acclaimed nineteenth-century English ice cream maker and culinary writer, frequently lectured on cookery and frozen desserts. See marshall, agnes bertha.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the United States had established land-grant colleges that provided an educational outlet for women in the form of home economics. While men learned agricultural and mechanical skills at these colleges, many women chose domestic science as a route for professional and educational fulfillment. The Boston Cooking School (of Fannie Farmer fame), New York Cooking School, and Philadelphia Cooking School continued the popularity of home economics and afforded women a new avenue for success in a growing profession. See farmer, fannie.

Baking and pastry instruction in an academic setting for career preparation is a modern phenomenon. Luxury hotels had already developed training centers for their staff, including cooks and bakers, in the early twentieth century. The Smith-Hughes Act of 1917 provided U.S. federal funds for vocational training, and by 1927 the Frank Wiggins Trade School in Los Angeles offered what is considered the first professional culinary training program, derived from its home economics program. In Chicago, the School for Professional Cookery (Washburne School), another early culinary program, began in 1938. Before World War II, only eight American culinary vocational programs existed. After the war, the newly passed GI Bill included provisions for assisting veterans with tuition costs, thereby adding additional federal funding to higher education. In 1947 the Culinary Institute of America (CIA) opened the first culinary program in a higher education setting. It was customary for these early cooking programs to include the basics of baking and pastry as a component of the culinary curriculum. The CIA was among the first colleges to pioneer standalone 15- and 30-week baking programs in the early 1970s.

In Europe, bakers traditionally comprised a separate guild from pastry makers. See guilds. Cooks belonged to another occupation entirely. In American higher education, baking and pastry arts merged into a single academic field as cooking schools proliferated and specialized in the 1980s and 1990s. The first certificate and degree programs in baking and pastry were offered by the CIA in the late 1980s, soon followed by Johnson & Wales University, California Culinary Academy, and the French Pastry School in Chicago (Washburne). The venerable Le Cordon Bleu in Paris, in operation since 1895, eventually added a separate bakery (boulangerie) diploma in 1998.

In 1976 the American Culinary Federation (ACF) established a formal culinary apprenticeship program, followed four years later by a baking and pastry apprenticeship. The status of chefs skyrocketed during this time, in no small part thanks to cooking shows and channels like the Food Network. Culinary and baking and pastry programs became firmly entrenched in the higher education landscape as hundreds of public and private programs began appearing in the 1980s. In 1986 the ACF established the Educational Foundation Accrediting Commission (ACFEFAC) to programmatically accredit culinary schools based on industry standards. By 1989 the ACFEFAC added separate standards to evaluate baking and pastry programs. Finally, in 1990, the U.S. Department of Education designated culinary and baking and pastry programs with their own Classification of Instructional Programs codes, used to track and report fields of study within the U.S. higher education system.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, by the early twenty-first century, there were more than 400 higher education culinary programs in the United States, down from a high of 700 a decade earlier. Only 189 colleges and institutes, however, offer a baking and pastry certificate or degree, and the ACFEFAC accredits 80 of those programs. There are, of course, innumerable specialized professional development courses for bakers, pastry cooks, and chefs, as well as similar offerings for the hobbyist. Common courses include artisan breads, European pastries, chocolate work, confections, showpieces, wedding cakes, sugar artistry, and plated desserts. The baking and cupcake craze, bolstered by popular culture and reality TV competitions, has only increased esteem for the baking and pastry arts.

See also pastry chef.

pastry tools, the varied implements from spoons to ovens used in making sweets, have remained essentially the same through the years. But in many cases, technology has improved their precision. Today’s well-calibrated ovens are a vast improvement over wood-fired ones that required a cook to be a keen judge of heat since they lacked any temperature control. In the past, cooks might put a piece of paper in the oven and judge the temperature by the time it took for the paper to turn brown. They timed baked goods by saying a prayer or a series of prayers. They would, no doubt, be impressed by the accuracy of today’s tools and their nearly infinite variety.

Today, thermometers are accurate, reliable, and highly specialized. Oven thermometers include the cable thermometer, which can be read without opening the oven door. Point-and-shoot infrared thermometers capture the invisible infrared energy naturally emitted from all objects. When aimed and activated, the thermometer instantly scans the surface temperature of an object from up to 2 feet away. This tool is useful for taking oven temperature as well as the temperature of different areas in the refrigerator or room. Instant-read thermometers are invaluable for determining temperatures of sugar syrups and baked goods. See stages of sugar syrup. They are so universal that chef’s jackets are usually designed with a pocket on the sleeve to hold one. Many pastry chefs still rely on their noses and sense of timing to judge when items are done; however, electronic timers are helpful when many things are baking at the same time.

Although spoons are one of the most basic baking tools, the symbol that best represents the pastry chef is the whisk. See whisks and beaters. Once made from a handful of twigs, wire whisks now come in an assortment of shapes and sizes and are useful for both stirring and beating mixtures. An enormous balloon whisk, 14 ½ inches in circumference, is more effective than a spatula for folding one mixture into another. Some pastry chefs make their own whisks for spun sugar by cutting the loops of a whisk to form a metal whisk “broom.”

Mechanical stand mixers are used for heavy-duty mixing in both commercial and home kitchens. Attachments include flat-paddle beaters for general mixing and whisk beaters that whip as much air as possible into a mixture. The latter are perfect for beating egg whites or batter for sponge-type cakes. Many cooks rely on hand-held electric mixers for small tasks.

Once found only in professional kitchens, food processors are now common in home kitchens. They are indispensable for grinding nuts and chocolate, grinding sugar to a superfine consistency, making pie crust, and puréeing fruit. Blenders, too, have traveled from the professional to the home baker. The hand-held immersion blender is an excellent tool for smoothly emulsifying ganache, cream sauces, and quantities too small for a stand mixer.

Scales are essential in a baker’s kitchen. Most bakers prefer the metric system, which makes it easier to scale recipes or formulae up or down.

Most new inventions build on already existing products. The microwave oven, invented in 1947, is a significant exception. It is unequaled for concentrating liquids without introducing caramelization and provides the fastest method for melting chocolate. See caramels.

Basics

An assortment of mixing bowls is essential for any baker. They may be made of stainless steel, earthenware, glass, or even bamboo. Glass bowls are microwavable, nonreactive, and do not retain odors. Double boilers, also known as bain-maries, may be a specialized set of two pans with the smaller one fitting over the larger, or simply a bowl set over a saucepan. They are valued for even and gentle heating in making sauces and curds and for melting chocolate.

Baking pans include round, square, rectangular, spring-form, tube, loaf, sheet, and muffin pans made from a variety of materials. Rimless baking sheets or the backs of sheet pans are used for baking cookies. Pie pans, tart pans with removable bottoms, round pizza pans, flan rings, and sheet pans are all among the baker’s supplies. Heavy-gauge aluminum pans with a dull finish are ideal. Dark or glass pans require baking at 25°F (−6°C) lower than the suggested temperature. Silicone is a poor conductor of heat and is therefore most effective for small pans used for cupcakes or financiers. See cupcakes and small cakes. Silicone has excellent release if cooled completely before unmolding.