laddu (also spelled laddoo), a round, sweet ball, is probably the most universally popular Indian sweet and one of the most ancient. It is given as an offering to deities at Hindu temples and served at many Hindu festivals and ceremonies.

The basic version (besan laddu) is made with chickpea (gram) flour, sugar, clarified butter, and cardamom powder. The flour is fried in the butter before adding the sugar and cardamom; when the mixture cools, it is formed into round balls around 1½ inches in diameter. They can be stored in an airtight container for up to a week.

Motichoor (meaning “crushed pearls”) laddu, another very popular variety, are made from tiny balls of deep-fried chickpea batter soaked in sugar syrup. Regional variants include laddus made from wheat flour (Rajasthan), sesame seeds (Maharashtra), rice flour (Kerala), and beaten rice or rice flakes (Andhra Pradesh); sometimes grated coconut or coconut powder, roasted chickpeas, nuts, and raisins are added.

The most famous laddu is the one served at the Sri Venkateswara temple in Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh (the most visited temple in India and the world’s second most visited holy place after the Vatican). Laddus are offered to Lord Venkateswara (an incarnation of Vishnu) and then distributed to the devotees. They are also sold in shops inside and outside the temple. These laddus are made from chickpea flour, sugar, clarified butter, cardamom, cashew nuts, and raisins. In 2008 they were granted Protected Geographical Indication status as a product with a specific provenance and composition. Another specialty of this temple is the kalyana (giant laddu), which is the size of a baseball.

See small cakes.

laminated doughs are made of layers of dough and fat, usually butter. Pâte feuilletée, or “puff pastry,” is considered the king of laminated doughs. Croissant and Danish doughs belong to the same family, and all follow a similar construction. See croissant and pastry, puff. No matter what form the laminated dough takes, its magical transformation in the oven depends on two elements: a flour-based dough and a fat. The pastry maker folds dough over the fat to enclose it, then rolls the dough out, and folds it over itself again and again, until it has dozens or even hundreds of very thin, alternating layers of dough and butter. As the pastry bakes, the steam from the fat releases and raises each individual layer of dough, creating a flaky mille-feuille (thousand leaves) effect. Proper puff pastry has many discernible layers of super-thin leaves of crisp, buttery dough.

The dough that folds over the butter, called detrempe, consists, at a minimum, of flour, water, and salt, although it usually contains some fat, too. This additional fat helps to prevent the principal fat being worked into the dough from bleeding into it as the dough is folded and rolled out.

The fat is traditionally butter. But animal fats, such as lard or duck fat, either used alone or in conjunction with butter, also have their place in these doughs. The hydrogenated vegetable fats used in mass production are second-rate, low-cost alternatives and are not recommended for reasons of quality and health.

Puff pastry dough typically contains around 75 percent butter relative to the weight of the flour, although some formulas, like those for inverted puff pastry and blitz puff doughs, use almost equal amounts of flour and butter. Croissant dough typically has a 3:10 butter-to-flour ratio of, which allows it to bake to a flaky texture on the outside and honeycombed within.

The pastry known as pithivier is an excellent example of a classic puff pastry product. The dough is rolled out to about ⅛ inch (2 centimeters) thick, cut into circles, layered with crème d’amande, topped with another layer of puff dough, scored in a pinwheel pattern, egg-washed, and baked. Pithiviers should rise 4 to 5 inches as they bake. For classic mille-feuilles, the rolled-out puff dough is lined with parchment and baked with another pan on top of it, so the pastries turn out flaky without rising more than around half an inch. They are a perfect platform for topping with mousses and pastry creams. Palmiers are made from sheeted puff pastry dough that is layered with sugar, rolled up, and sliced into layered palm shapes that bake up crisp, sweet, and delicious.

Croissants are made from a leavened dough that rises thanks to the addition of commercial baker’s yeast, a wild-yeast starter, or a combination of the two. Unlike puff pastry dough, croissant dough is sweetened, and it is hydrated with water and milk; whole eggs or egg yolks are also often added.

Croissant dough and American Danish dough are very similar, the primary difference being that croissant dough usually contains more butter and therefore bakes up flakier. A properly made croissant should shatter when bitten into and reveal a characteristically honeycombed crumb from the dough’s fermentation and its gases that expand during baking. Croissants’ taste should have a subtle acidity that balances the fat of the butter, without tasting at all sour.

See also butter; france; pie dough; and shortening.

Latin America has essentially orderly, solid traditions of sweets that speak to the people’s love of habit, not novelty. There is a soothing, reassuring stability in Latin American sweets that is also sensuous and magical.

For Latin Americans—who crave flavorful savory foods built in layers; who welcome the sting of hot peppers, the acid touch of citrus juices or vinegar, and the bite of raw onions in table condiments; and who seek vivid contrast between salty, sweet, bitter, acid, and the savory sensation of umami—dessert (postre) is meant to put a calming end to the sensory ride that is the Latin meal. Latin Americans are assertive in their savory cooking, and subtle, often minimalist, when making sweets and desserts.

The pre-Columbian peoples of Mesoamerica enjoyed honey-based treats and ambrosial tropical fruits, but the fundamental ingredient of the Latin American dessert tradition arrived in the New World with the Spanish after 1492 in the form of sugar and the sugarcane from which it is derived. See sugar and sugarcane. Muslims had introduced this perennial grass to the south of Spain in the eighth century, and tropical America proved an ideal environment for the South Asian native.

From Mexico to the southern tip of South America, Latin Americans are like a family that can trace its heirloom sweets back from generation to generation to a common source—the Spanish and Portuguese convents and monasteries that were founded in the early colonial period. See convent sweets.

The cooks who developed and spread the Latin dessert-making tradition from Mexico and the Caribbean to the southern tip of Argentina worked their alchemy in the kitchens of the monasteries and convents that Spanish and Portuguese religious orders founded beginning in the sixteenth century. After the armies of conquest had subdued the native peoples, it fell to Franciscans, Dominicans, Jesuits, and others to propagate the Christian gospel and Iberian culture in the New World. The friars set about creating towns based on Iberian models and recreating the natural world they had known in Europe. They carried sugarcane and fruits such as peaches, apples, figs, grapes, plums, quinces, bananas, and oranges from one part of the Spanish colonial empire to the other.

The friars developed a reputation as gifted cooks who knew how to turn both Old and New World ingredients into tempting sweets, but it was the nuns who firmly planted Spanish sweet-making traditions in the New World. This was particularly true of nuns from Andalusia, which Christian rulers had wrested from Islamic control, and where convents were the repositories of Islamic recipes for sweets. See islam.

Alfajores, popular cookies often sandwiched together with dulce de leche, are offered for sale in Buenos Aires. jill schneider / national geographic creative

The sisters were a peripatetic lot. Nuns of the Regina Angelorum monastery on Hispaniola (the island shared today by the Dominican Republic and Haiti) traveled to Cuba and Peru. The first nuns of the Santa Clara convent in Caracas, Venezuela, came from the Santa Clara convent in Santo Domingo, and the first nuns of the Carmelite convent of Trujillo, Peru, were from a sister convent in Quito. Such movement contributed to the dissemination of ideas and recipes.

The nuns’ initial mission was to educate native girls who had been converted to Christianity by the friars. As more Spanish families settled in the colonies, some convents became boarding schools for upper-class young women, who brought with them retinues of servant girls. The nuns kept their charges virginal and prepared them to be good wives, teaching them cooking, dessert making, and other household skills. These lessons were at the same time imparted to their native, mestizo, and African servants.

Teaching monasteries benefited from monetary gifts from the parents of their aristocratic pupils, but nuns such as the Carmelites, who were cloistered and bound by vows of poverty, had to find other means of sustaining themselves. When times were hard and donations fell short, they produced special sweets to sell to the public. In a 1755 letter to his sister in Madrid, Guillermo Tortosa described the nuns of a convent in Puebla, Mexico, as “chubby, sweet white angels with heavenly hands.” With those hands, he explained, they prepared delectable sweets for an important town festival. Their output, he wrote, included candied peaches, guava, pear, and quince, a caramelized goat’s milk sauce called cajeta, egg sponge, and mamón, a type of genoise. Some of the sweets he described were traditional Spanish desserts, such as tocino del cielo (“heaven’s bacon,” an egg yolk custard), while others were Iberian desserts made with New World ingredients, such as the Brazilian egg and coconut custard quindim.

The story was repeated throughout New Spain. The nuns of La Concepción in Mexico City prepared sweet empanadas, the convent of La Encarnación in Lima was famous for its almond pastes, the Carmelites of Puebla were known for dulce de cielo (an egg-rich custard), and Puebla’s Santa Clara convent was praised for a marzipan made with sweet potato (camote) paste mixed with unrefined sugar and molded into small sweet potato shapes. This heritage is echoed today in the names of Latin American desserts such as suspiros de monja (nun’s sighs), huevos espirituales (spiritual eggs), and suspiritos de Maria santísima (little breaths of the most Holy Mary). Mexico and Peru, which were epicenters of viceroyal political power, had the greatest number of religious institutions, and therefore richer and more complex sweet cuisines than the Caribbean islands, where organized religion played a lesser role.

Not as rooted in convent traditions but reflecting a long-standing Spanish and Portuguese love affair with the combination of sweet and crunchy are the “fruits of the frying pan” (frutas de sartén), the fanciful name given in Spanish medieval cookbooks and later in colonial cookbooks to crisp, deep-fried pastries sprinkled with sugar or doused with syrup. See fried dough. Another Islamic legacy in Latin America is fruit cooked in sugar syrup, either to sweeten the fruit for a silky dessert or to preserve it as an intensely concentrated confection, jam, paste, or candy. With an abundance of sugarcane and a cornucopia of tropical fruits, plantation kitchens produced prodigious amounts of guava marmalade, bitter orange shells in syrup, and many other stovetop desserts born of this mingling of traditions.

Perhaps the most beloved dessert tradition in Latin America—and yet another Iberian legacy—can be found in the many variations on the theme of sugar cooked with milk, egg yolks, or both, such as long-simmered rice puddings, the pan-Latin caramelized milk pudding or sauce called dulce de leche, and natillas that are like airy custards. See custard and dulce de leche.

Guavas or guava shells, native squashes, or cashew apples might take the place of peaches or quinces in fruit desserts and pastes. Pumpkin seeds, cashews, coconut, peanuts, and even starchy plantains came to fill the place of Spanish almonds and other nuts in the Latin interpretation of nougats, marzipan, and other candies. See marzipan and nougat. Allspice, vanilla, and cinnamon-scented ishpingo (Ocotea quixos) began gracing the same custards as traditional cloves and cinnamon. The “fruits of the frying pan” received novel additions such as pumpkin or corn, while yuca and sweet potatoes were used to make thick, sweet creams and puddings.

There are other important ethnic footnotes to this essentially transplanted Spanish and Portuguese story. Immigrants from many parts of the world brought their own favorite desserts to Latin America or found particular commercial niches there. For example, one can recognize a large, abiding African presence in the world of Latin sweets. In the massive kitchens of tropical plantations, or in any urban kitchen presided over by African matrons, a hybrid sweet cuisine came to be. But unlike the influence of Africans in other areas of cooking, it began as a matter of adopting the Spanish and Portuguese models. Later, emancipated slaves used the skills learned on plantations and in the homes of the rich to develop a unique repertoire of sweets.

Finally, to the mystification of cooks from other traditions, canned milk made an indelible mark on the map of Latin sweets. That fresh milk can be difficult to produce and store in the tropics was surely a factor, but what is at work is a cultural preference born a century ago, when U.S. companies began producing and exporting sweetened condensed milk and evaporated milk. Custardy sauces and flans made with these convenience products are a late but important chapter in the story of Latin America’s centuries-old love affair with sweetness. See evaporated milk; flan (pudím); and sweetened condensed milk.

See also brazil; candied fruit; egg yolk sweets; fruit; fruit pastes; fruit preserves; marmalade; mexico; portugal; spain; and zalabiya.

Latini, Antonio (1642–1692), was among the first to write about sorbetto. The author of Lo Scalco alla moderna (The modern steward), Latini rose from street urchin to knight in a life fit for a fairy tale. He was born in a small town in the Marche region of Italy in 1642. Orphaned at five, he seemed destined for poverty. But he found work as a servant and learned to read, write, cook, and manage a noble household. Eventually, he became steward to the Spanish prime minister in Naples, and in 1693, three years before his death, Latini was knighted.

Published in two volumes in 1692 and 1694, Latini’s book was, as the title promised, modern for its time. He recorded some of the first recipes using tomatoes and chilies and wrote about cooking with fresh herbs rather than sweet spices. He described the trionfi (triumphs)—sparkling sugar sculptures, gleaming jellies, and shimmering ices—that dazzled the eye on regal banquet tables. See sugar sculpture.

Although Latini asserted that everyone in Naples was born knowing how to make sorbette, he was among the first to write about them. The vocabulary of ices and ice cream evolved over time. Latini did not use the word gelato, and instead of today’s masculine sorbetto (singular) and sorbetti (plural), he used the feminine sorbetta, sorbette. His flavors included lemon, sour cherry, and strawberry. He also made a cinnamon ice with pine nuts, and two different chocolate ices. His Sorbetta di Latte, milk sorbet, was flavored with candied citron or pumpkin. None of Latini’s sorbette contained eggs or cream. His recipes lacked detail since, he said, he did not want to upset professional sorbet makers by revealing their secrets.

See also confectionery manuals; ice cream; and italy.

lauzinaj (lawzinaj, lawzinaq, luzina) is a pastry and confection whose main ingredient is almonds (in Arabic, lauz). “Supreme judge of all sweets,” “stones of paradise,” “food of kings”—such were the glowing epithets heaped on this quintessentially medieval dessert of the Arab-Muslim world. No wedding should be without it, and dreaming of it presaged jolly times. In addition to its seductive taste, lauzinaj was believed to have beneficial medicinal properties. It helped induce sleep, nourish the brain, and ripen cold humors in chest and lungs.

Medieval Arabic recipes describe making lauzinaj in two ways. Lauzinaj mugharraq (drenched lauzinaj) consisted of sheets of pastry as thin as the inner membrane of eggs, stuffed and rolled with ground almond or other nuts like pistachios or walnuts that had been mixed with an equal proportion of sugar and bound with rosewater, and sometimes luxuriously perfumed with musk, mastic, and ambergris. See ambergris and flower waters. The rolled pastry was then cut into smaller pieces, arranged in a container, and drenched in fresh almond or walnut oil and rosewater syrup. These dainty almond rolls were precursors of baklava, a dessert closely associated with Ottoman cuisine. See baklava. Nowadays such rolls are more commonly called asabiʾ il-ʿarous (bride’s fingers) in the Arab world.

Lauzinaj yabis (dry lauzinaj) was a confection reminiscent of marzipan. It was either made without cooking by blending equal amounts of finely crushed skinned almonds and sugar, bound and scented with rosewater, musk, and camphor; or else it was cooked by adding finely ground almonds to a boiling honey or sugar syrup, which was beaten and thickened to taffy consistency before being cooled and shaped. Whether raw or cooked, dry lauzinaj was artistically formed into animals and vegetables by means of special molds; rolled into cylinders and cut into fingers; or spread onto a greased surface and cut into triangles and squares.

The legacy of lauzinaj yabis proved to be far-reaching as it found its way to medieval Europe via Muslim Spain, the Crusaders, and Latin translations of books on dietetics and cookery, where it was recorded as losenges or lesynges, and by other spellings as early as the thirteenth century. Subsequently, while similar almond confections came to be called “marzipan” and “macarons” in Europe, the Arabic-derived name “lozenge” came to designate cough drops, regardless of shape or content. See lozenge; macarons; and marzipan. The diamond shape so closely associated with lauzinaj further gave its name to the geometric form known as a lozenge. Evidence of this connection to shape can be found in the long tradition of the Iraqi diamond-shaped confection called lauzīna, whether it is made with almond, coconut, quince, or orange rind.

See also middle east and persia.

layer cake —the home cook’s dessert showpiece—consists of two or more sponge or butter cake rounds with icing, jelly, or cream between the layers. After chemical leaveners, improved ovens, and tools became widely available around 1870, cooks began to create an astonishing array of layer cakes. See chemical leaveners. Sponge, pound, and butter cakes were used to form the layers, with flavors as varied as rosewater, vanilla, chocolate, spice, fruit, and carrot. See pound cake and sponge cake.

Recipes for mille-feuille, puff pastry with jelly or cream between the layers, were described in cookbooks in seventeenth-century France and eighteenth-century England, foreshadowing the layering of cakes. See pastry, puff. “Jelly cakes” first appeared in the 1830 edition of Eliza Leslie’s Seventy-five Receipts for Pastry, Cakes, and Sweetmeats. The cake batter was initially baked on griddles like pancakes but later was spread in shallow jelly cake pans or made into thicker cakes that were baked and then cut horizontally after cooling. Jelly cakes became enormously popular; in 1891, 600 competitors entered the Illinois State Fair Jelly Cake competition. The winner caused a controversy by using Angel Food Cake for her layers. See angel food cake.

An icing of egg whites and sugar, often with coconut, replaced jelly between the multiple layers of white butter cake to form the White Mountain Cake popular in the 1860s. The filling for the Lady Baltimore Cake, named after a delectable cake described in the 1906 novel Lady Baltimore, included cooked figs, nuts, and dates, while the Lane Cake, created a few years earlier in Alabama, used bourbon, raisins, nuts, and coconut. Nuts and coconut adorn the more recent German Chocolate Cake that calls for Baker’s German Sweet Chocolate. See baker’s. Boston Cream Pie, made with sponge cake filled with custard and topped with chocolate glaze, is now the official dessert of Massachusetts. See boston cream pie. Another official state dessert is Maryland’s multilayered Smith Island Cake, consisting of yellow cake with rich chocolate fudge icing. Tall stacks of 10 or more thin cakes either iced or spread with jelly were once common for holidays and special occasions in the American South, although they are now rarely prepared at home. Such cakes include the dried apple–laden Tennessee Stack Cake and Kentucky Jam Cake. See appalachian stack cake.

In nineteenth-century Europe, several decadent cakes and tortes, such as the Sachertorte and Dobos torte, were created by professional bakers. See dobos torte and sachertorte. Mrs. Beeton’s influential Book of Household Management introduced the British to the Victoria Sandwich, a two-layer cake with jelly, in 1861. This cake is still served at teas. Other well-known European cakes include the Opéra Gâteau, conceived in a Paris bakery in the 1930s and made of almond sponge cake with coffee and chocolate filling, and the Black Forest Cake, a rich concoction of thin chocolate cake layers, cherries, kirsch, and whipped cream. See black forest cake. The Dutch-Indonesian cake Spekkock or lapis legit is made by baking very thin layers in succession to form a tall, multilayered spice cake.

Although layer cakes of a single color were often baked, two-layer cakes could combine silver (white) and gold (yellow), or light and dark (spice and chocolate). Three layers might have a contrasting color sandwiched between two matching cakes, while four layers could feature completely different colors, as in the Harlequin Cake. The stacking of colors could be quite striking. Ice-cream and Cakes, from 1883, offered a version of Neapolitan Cake with red, white, and green layers to replicate the 1848 flag of Italian unification. The Angel Cake still popular in the United Kingdom (not to be confused with American Angel Food Cake) has three layers—white, pink, and yellow—baked in square pans, cut into bars, and then topped with white icing. An 1877 version of Dolly Varden Cake called for four layers of chocolate, white, rose, and yellow, although later recipes generally alternated only light and dark layers. See dolly varden cake.

Creative layer cake designs include the Checkerboard Cake, formed by three layers filled with alternating rings of light and dark batter. Britain’s Battenberg Cake from the late Victorian era is a loaf composed of two upper and lower squares of pink and yellow cakes encased in almond marzipan. Cakes can be formed into elaborate three-dimensional shapes by using special pans or by carving the cake layers accordingly. Although tiered wedding cakes tower over bite-sized petits fours, both are technically layer cakes. See wedding cake.

American cookbooks for home cooks contained a variety of layer cakes. Some offered over 30 recipes; in 1907 May Elizabeth Southworth published One Hundred & One Layer Cakes. One of the earliest uses of the term “layer cake” was in a section header in an 1873 Ohio community cookbook, the Presbyterian Cook Book. Previously, recipes for layer cakes had appeared under specific names, such as Jelly Cake or Ribbon Cake. The proliferation of layer cakes caused a naming frenzy, which continues in contemporary cookbooks, although the popularity of this type of cake has diminished.

See also beeton, isabella; icing; south (u.s.); and torte.

lead, sugar of, known to chemists as lead(II) acetate or Pb (CH3COO)2, gets its name not from its undeniable resemblance to rock candy but from its taste. It is sweet, roughly as sweet per teaspoon as sugar—and only slightly more lethal than strychnine.

In the nineteenth century, when mercury was used as a remedy for maladies as serious as syphilis and as commonplace as constipation, sugar of lead (saccharum saturni) was also part of the European pharmacopeia. Ironically, given that one symptom of acute lead poisoning is an upset stomach, the chemical was occasionally prescribed in low doses for intestinal maladies. Lead poisoning came to be called “colic of Poitou,” due to the once widespread use of lead in that winemaking region.

Sugar of lead is chemically classified as a salt, an array of positive ions and negative ions, usually crystalline in appearance. The iconic example, table salt, comprises equal numbers of positive sodium ions and negative chloride ions in a cubic array. Perhaps surprisingly, not all salts taste salty. Though sodium chloride is the touchstone of salty tastes, there are literally millions of known salts, with tastes ranging from bitter to sweet.

Lead acetate—dipositive lead ions interspersed between negatively charged acetate ions—is a sweet salt. So is lead carbonate, as are salts of yttrium and beryllium. So many beryllium salts are notably sweet that the original name for the element was glucinium, from the Greek for “sweet.” The obvious downside to all these noncaloric sweeteners is their toxicity. Ingesting as little as 3 teaspoons of sugar of lead would be quickly fatal to the average 70-kilogram Roman emperor.

The Romans were reputed to have used lead acetate as a sweetener. Sapa, and its more concentrated sister defructum, were syrupy sweeteners produced by boiling down must, a mildly fermented grape juice. See grape must. Must contains acetic acid, a source of acetate ions, which will react with the metal vessels to produce metal acetates. Copper salts are bitter, imparting an undesirable taste to the sapa, but lead salts are sweet and so did not affect the taste of the sweet syrups. Pliny the Elder notes this in his Natural History with regard to the production of sapa and defructum: “Leaden vessels should be used for this purpose, and not copper ones….” Chemical analyses of sapa produced according to recipes dating from the classical Roman period, using kettles of similar metallic composition as those found at Pompeii and other sites, suggest that the lead content of sapa was 850 milligrams per liter, many thousand times higher than what is generally allowable in drinking water. Even diluted and used sparingly, sweetening with sapa posed a serious risk.

Interestingly, sapa’s sweetness does not result from sugar of lead. The sugar of lead in a liter of sapa is equivalent to roughly a pinch of sugar, imperceptible to most palates. However, the concentrated grape juice in sapa contains both the sugars glucose and fructose at concentrations that would mimic the sweetness of 1 cup of table sugar per liter, completely drowning out any sweetness attributable to the sugar of lead. Neither sapa nor defructum would be all that sweet to modern taste buds; simple syrup, which has similar culinary uses to sapa, contains about 4 cups of sugar per liter.

The practice of adding lead metal to fermenting alcoholic beverages such as wines and ciders, leading to the in situ formation of sugar of lead, did not end with the Romans but was commonplace in Europe until the modern era. Lead and lead salts are widely available, and they are as deadly to bacteria as they are to humans; vintners observed that filtering fermentation mixtures through lead sieves or dropping some lead shot into bottled wine noticeably reduced spoilage. A firm connection between ingesting low levels of lead in these beverages and lead poisoning was finally made in the early nineteenth century, in part because of the correlation between outbreaks of colic of Poitou and the arrival of wine shipments containing lead.

leaf, gold and silver, are produced the same way, by pounding a piece of the metal between vellum pads until it is no more than a few micrometers thick. As inert metals, both are harmless to the human body and, although indigestible, are consumed in such small quantities that they simply pass through the digestive system.

In the nineteenth century jellies were sometimes decorated with either silver or gold leaf, and Mrs. Beeton describes a Christmas jelly of red currant decorated with both gold and silver leaf to imitate flames. See beeton, isabella. In contemporary European and American sugar craft, both types of leaf are used. Sugared almonds, coated in silver and gold leaf, are often served at weddings. A cake to celebrate a silver wedding anniversary (25 years of marriage) may have edible silver leaf over the icing, although removable silver decorations are used more often. Fancy chocolates are occasionally decorated with a small amount of gold leaf, to suggest luxury, and gold dust is sometimes sprinkled on cocktails and champagne. In Great Britain, a specialist supplier called Wright’s of Lymm sells gold and silver leaf for culinary use. Dust, petals, and flakes made of gold and silver sell in greater quantity than the leaf.

Gold and silver leaf are widely used to decorate confectionery in the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent, especially in Pakistan, Northern India, and Bangladesh. See south asia. Silver is used more widely than gold. In Arabic, gold and silver leaf are both known as waraq, which means “leaf” or “paper.” Both types of leaf are called vark in Hindustani. The word might also derive from the Sanskrit word varaka, which means a “cloak” or “cloth,” or something that covers something else. In traditional Ayurvedic medicine, silver is regarded as an antimicrobial astringent, and gold is regarded as an aphrodisiac. In the bazaar at Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh, gold and silver leaf are manufactured in the traditional way. It is claimed that both metals hold aphrodisiac properties, which possibly implies that their health benefits are secondary to the decorative qualities and air of opulence.

A wide variety of Indian sweets are decorated with silver. Gold leaf features in the extremely rich and luxurious cuisine of the Nawabs, notably in a sweet bread pudding called shahi tukra, but it is less frequently used than silver. Silver leaf is especially favored for barfi, a type of fudge made from condensed milk. See barfi. It can also be used in savory dishes, especially korma—the fact that a korma is generally made with yogurt implies that in India silver is associated with creaminess.

Recently, some dispute over the vegetarian nature of vark has arisen, mainly because of its method of manufacture between vellum pads. Strict vegetarians do not eat vark. Purity is more of an issue, with many tested samples of vark found to contain traces of nickel, lead, copper, chromium, cadmium, or manganese.

See gingerbread.

ledikeni is made by forming a mixture of chhana (fresh curd cheese) and flour into ping-pong–sized balls and stuffing them with cardamom-scented nakuldana (sugar granules). The balls are then fried and subsequently soaked in sugar syrup to yield a slightly crisp exterior and soft, juicy interior; the melted sugar filling bursts in your mouth as you bite into this sweet.

The various legends of ledikeni’s origin point to a confectioner’s tribute to a colonial ruler. Ashoke Kumar Mukhopadhyay, a connoisseur of sweets, recounts (1999) that the sweet was prepared by the well-known confectioner Bhim Nag to commemorate the birthday of Countess Charlotte Canning, popularly referred to as Lady Canning, wife of the Indian Viceroy Charles Canning. Christened after the confectioner, Bhimnag is a famous sweet shop in North Kolkata owned and managed by Nag’s family, whose roots can be traced to the Hooghly district. In another story, the shop is credited with the invention during Lady Canning’s visit to Calcutta (Kolkata’s earlier name) in 1856, before the Sepoy Mutiny. In a travelogue piece on sweetshops in Kolkata, Rimli Sengupta states that the sweet was created by Bhimnag to celebrate her visit. Though Lady Canning succumbed to malaria within five years of her arrival, her name has come to be associated with the popular sweet that continues to occupy a revered position in postcolonial Bengal.

Bhimnag, the shop known for the discovery of ledikeni, has a history of christening sweets in honor of its patrons; other popular ones include Nehru Sandesh, created in honor of Motilal Nehru’s visit to Calcutta in 1927–1928; and Ashubhog, named after the shop’s patron Sir Ashutosh Mukhopadhyay, an eminent Calcutta author. See sandesh. However, Nandalal Bhattacharya (1999) points to a different tale of origin. According to this version, after the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, confectioners in the Bengali city of Berhampore prepared a special sweet to honor Lady Canning, who was supposedly touring with her husband, the viceroy. The sweet was dubbed “Lady Canning,” but the Bengali tongue transmuted it into ledikeni. In the decades following Lady Canning’s untimely death, ledikeni became the sweet of choice at fashionable Bengali gatherings.

Although ledikeni is similar to pantua (another fried sweet), the molten sugar syrup of lightly flavored cardamom powder makes it distinctive. It is impossible to know whether or not Lady Canning ever tasted her eponymous confection, but the sweet continues to occupy a prominent place in the pastry cases of Bhimnag and other sweetshops throughout West Bengal.

legislation, historical, covers the laws affecting the availability of sweets. Historically, the single most important law of this type has been the protective tariff on sugar. Tariffs and other trade protections have been enacted—and, notably, repealed—by virtually every major sugar-producing and sugar-consuming nation since at least the sixteenth century. Without tariff protection, large-scale plantation sugar production in the Caribbean and Pacific islands might never have developed, nor would the sugar-refining industries in Europe have had such phenomenal success. Ultimately, the steady increase in per capita sugar consumption in the modern period depended on trade policies that stimulated production and dramatically lowered the price of sweets. See plantations, sugar.

Mercantilist policies in Great Britain, France, Spain, and Portugal restricted trade to their respective colonies before the eighteenth century. European colonial powers reserved for themselves the right to buy and refine the sugar from their own colonies, which could neither buy nor sell from foreigners, except at the cost of high trade duties paid to the colonizing country. Planters, importers, and refiners thus enjoyed a state-authorized monopoly, which encouraged them to invest in sugar plantations. Gradually, through the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, all European nations moved toward what they called “free trade.” Free trade did not mean that there were no tariffs. Instead, it meant that international trade was allowed, and that the colonies could sell their goods more widely. As a result, larger quantities of sugar—most of it produced by slave labor—entered the world market at ever-cheaper prices. Sweetened tea, jam, candies, cakes, and cookies grew in popularity and became affordable for middle- and eventually even low-income consumers.

In the late nineteenth century, Germany and other European countries promoted their domestic sugar beet industries by paying subsidies to exporters. The resulting competition between beet and cane sugar brought down world sugar prices even more. High sugar tariffs in the United States encouraged farmers to grow sugar beets and also stimulated huge increases in cane sugar production in Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Cuba, all of which paid low or no tariffs. Higher production in the United States and its dependencies brought lower prices, leading to a considerable expansion in the range and sophistication of sweetened foods.

Since the 1990s tariff protection has fallen out of favor worldwide, replaced by multilateral free trade agreements and import quotas. The United States restricts its sweetener market through marketing allotments and flexible tariffs tied to import quotas and domestic consumption. As a result of its multilateral trade obligations, the United States waives import tariffs on a significant amount of imported sugar. Mexico imposed antidumping tariffs on high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) in the late 1990s in an attempt to protect its sugar industry against the U.S. corn industry. The United States filed complaints with international trade organizations, after which Mexico rescinded the tariffs but imposed a 20 percent consumption tax on HFCS-sweetened beverages. For several years Mexican Coca-Cola enjoyed a special following in the United States because it was cane sugar–sweetened and presumably had a more authentic flavor. The United States and Mexico resolved the dispute in 2006, and HFCS now enters the Mexican food supply while Mexico exports cane sugar to the United States. Some commentators note that U.S. corn subsidies have contributed to the overabundance of cheap, corn-sweetened beverages and foods in North American diets.

Legislation regarding sanitation and food purity has also shaped the history of sweets. Adulterants were formerly quite common in candy and sugar in Europe and the United States. See adulteration. Artificial colors in candy were especially dangerous, since bright colors were achieved with lead, copper, and other hazardous elements. France passed the first general laws prohibiting food adulteration in 1802. By the 1830s it had enacted prohibitions on a range of chemicals, minerals, and other adulterants. In Britain and the United States, news reports of children poisoned by cheap candies galvanized public opinion. Great Britain implemented pure food laws in the 1860s, and the United States did so in the 1900s. England and the United States resisted stringent national laws because they seemed to impinge on free trade (in the British case) and independence from government interference in private affairs (in the American case). These laws, along with inspections intended to assure hygienic conditions in candy factories, were only sporadically enforced. In the twentieth century new methods of laboratory analysis have revealed the dangers of contamination and made it easier to test candies. In 1963 the Codex Alimentarius was created to coordinate food safety and hygiene standards for international trade. It has no regulatory capacity but issues guidelines and model national legislation. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration regulates food safety and hygiene.

In light of public health concerns over rising rates of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease in the 2000s, some reformers have proposed consumption taxes on sweets as a way to shape consumer behavior. By imposing special taxes on high-calorie, low-nutrient foods such as soft drinks, they hope people will eat less of those foods. Hungary imposed such a tax in 2011. Denmark debated whether to do so, as did New York City. Policy analysts remain uncertain whether such measures improve health outcomes, or if they unnecessarily stigmatize poor people’s food choices.

See also corn syrup; fructose; sugar and health; and sugar trade.

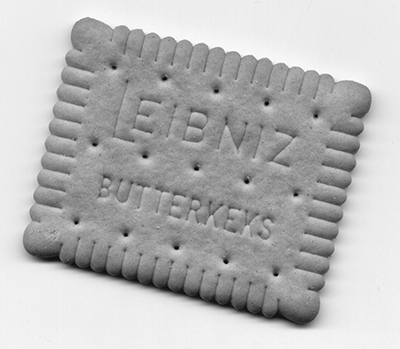

Leibniz Keks, flat, crisp biscuits made from flour, butter (12 percent), sugar, and eggs, represent the very definition of sweet biscuits for generations of Germans, having been produced since 1891. Back then, the pioneering Hanover merchant Hermann Bahlsen (1859–1919) imported modern tunnel ovens from Glasgow, designed packaging as distinctive as the biscuits’ advertising, and named them after the German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a native of Hanover. From the start the convenient little boxes of biscuits were aimed at hungry travelers in an age of urban growth and an expanding network of railways.

Five years earlier Jean Romain Lefèvre and Pauline Isabelle Utile in Nantes had come up with the Petit Beurre LU biscuit in exactly the same design—a flat rectangle with scalloped edges. English biscuits seem to have been the inspiration for both, and indeed Leibniz Keks were originally called Leibniz cakes. But Bahlsen soon switched to the phonetic German version of the word. This move might have been a nod to the Germanification trend of the era, which frowned upon foreign words. However, keks has become a false friend, since it stands for “cookies” or “biscuits” rather than cake—its official dictionary meaning since 1911 when it entered the definitive Duden. During World War I Bahlsen advertised the Leibniz Keks as soldiers’ rations, even commissioning a postcard series from well-known artists to promote them.

These crisp biscuits, named after the German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leipniz, were originally packaged as convenient travelers’ snacks. During World War I they became soldiers’ rations, and today they are a popular everyday treat. rainer zenz

Although still family-owned, Bahlsen has grown into an international conglomerate specializing in cookies and savory snacks like potato chips. In 2013 the large gilded bronze Leibniz Keks hanging outside the company’s Hanover headquarters disappeared under mysterious circumstances (in ransom notes, the thief posed as the Sesame Street Cookie Monster); it reappeared just as mysteriously some months later.

Leibniz Keks are an essential ingredient for Kalter Hund, an icebox cake popularized in the late 1960s and early 1970s that has become fashionably retro today: Keks are layered in a rectangular cake pan with a rich mixture of cocoa, sugar, and coconut butter, then chilled and cut into slices to serve.

lemonade, a refreshing beverage that has been enjoyed throughout the world for hundreds of years, consists simply of lemon juice, water, and sugar. Lemons and sugar—both originating in India and following the same route to the Mediterranean—are a natural pair. The addition of water creates a cooling drink in hot climates, such as India, where salt is often added. Lemonade can be served with ice, as is French citron pressé, or frozen into granita, Italian style. See italian ice.

Lemonade is appreciated primarily as a pleasurable and refreshing beverage, but it has also long been valued for its healthful qualities. The earliest written recipes for lemonade, some flavored with fruits or herbs, appeared in Arabic, in a twelfth-century medical cookbook On Lemon, Its Drinking and Use. The author, Egyptian physician Ibn Jumayʾ, recommended the drink for stimulating the appetite, aiding digestion, curing inflammations of the throat, and even treating “the intoxicating effects of wine.” Lemonade, he wrote, “quenches one’s thirst and revives one’s strength.”

Health recommendations for lemonade, sometimes including such nourishing ingredients as barley, eggs, or sherry, appeared in “invalid cookery” sections of British cookbooks starting in the sixteenth century. Lemonade’s most important contribution to health was certainly its strong dose of vitamin C, even before the human need for this vitamin was recognized. Scurvy killed more than 2 million sailors before the British Royal Navy in 1795 ordered that the sailor’s daily rum-and-water grog should henceforth contain lemon juice, which effectively ended the 300-year plague of the disease. (Lime juice was used for a time in the mid-nineteenth century, but it was found to be less effective than lemon juice. This brief period when lime juice was used was what caused some to dub the British sailors as “Limeys.”)

In northern Europe before the seventeenth century, the high cost of both lemons and sugar restricted lemonade consumption to a necessary expense for the sick or an extravagant pleasure for the rich. But after sugar prices collapsed in the early 1600s (due to the expansion of West Indies plantations), lemonade became much more affordable. Limonadiers, or lemonade men, dispensed the hugely popular beverage from metal tanks carried on their backs. French cookbooks of the mid-1600s offered scores of lemonade recipes, flavoring the drink with spices, flowers, and scents including ambergris, musk, cinnamon, rosewater, jasmine, and orange blossoms.

The practice of spiking lemonade with alcohol is nearly as old as the beverage itself, but the American temperance movement of the mid-1800s endorsed the innocent nonalcoholic version as a favored “temperance drink.” First Lady Lucy Webb Hayes, who shunned alcohol in the White House of the 1870s, was dubbed “Lemonade Lucy,” adding to the beverage’s publicity. Even as the temperance movement faded, lemonade remained a refreshing and wholesome summer drink of choice in the United States, at picnics and carnivals, circuses and fairs. See fairs. Italian immigrants operated pushcarts or stands selling iced lemonade in the summer, in cities and at the seashore. Pink lemonade was associated with circuses, although the story of its origin, which attributed its invention in the 1870s to a circus vendor named Henry Allott after he accidentally dropped red cinnamon candies into a batch of lemonade, is likely apocryphal. Cookbooks of the period suggested flavoring lemonade with pink or red fruit such as watermelon, strawberries, or cherries, so pink lemonade was nothing new.

In the late 1800s many vendors used tartaric acid to imitate lemon flavor, merely floating lemon slices on the surface to resemble the genuine article. Sunkist Growers, a citrus marketing cooperative, introduced frozen lemonade in the 1950s, promoting it as “the coolingest cooler of them all.” Bottled lemonades and powdered lemonade mixes, some containing citric acid and artificial colors, vary in quality. In Great Britain, “lemonade” or “fizzy lemonade” may refer to a commercially produced, carbonated, lemon-flavored drink quite different from the natural homemade beverage of lemons, sugar, and water.

Lenôtre, Gaston (1920–2009), rose from humble beginnings on a small farm in Normandy to become one of France’s most successful patissiers, caterers, and retailers. As founder of the renowned Lenôtre cooking school in Plaisir, west of Paris, he trained hundreds of professional pastry chefs. At the time of his death, Lenôtre was head of a worldwide group of 60 boutique pastry shops in 12 countries, as well as proprietor of the Michelin three-star Paris restaurant Le Pré Catalan. Revenues from his empire totaled $162 million in 2008.

Lenôtre fits into a continuum of French master pastry chefs that began with Marie-Antoine Carême (1786–1833) and continues with Pierre Hermé (1961–), who, having served an apprenticeship with Lenôtre from the age of 14, has called Lenôtre the greatest influence on his career. See carême, marie-antoine and hermê, pierre. While Lenôtre never renounced the butter, cream, and cheese that are at the heart of the cuisine of Normandy, he is best known for modernizing pastry making in the 1960s. He lightened the era’s traditionally heavy sweets by substituting airy mousses, flourless creams, and tropical fruit purées for the dense flour- and sugar-laden cake layers and buttercreams of that era.

His creations presaged the advent of nouvelle cuisine in the early 1970s, which demanded a return to simple presentations and the freshest ingredients. Led by the French chefs Paul Bocuse, Roger Vergé, Jean and Pierre Troisgros, and others, the nouvelle cuisine movement grew out of the spirit of revolt spurred by the student riots that took place in Paris in 1968.

Lenôtre’s aesthetic could be small and chic, or highly dramatic. His chocolates and individual pastries were models of precision, balancing flavors and textures, and exquisitely presented. For the 1984 marriage of Victoire Taittinger (of the Taittinger Champagne–producing family), he created a massive, multitiered cake decorated with bunches of spun-sugar grapes (for the bride) and rocket ships made from brown nougat and multifarious éclairs (for the groom). To celebrate Lenôtre’s eightieth birthday in 2000, his apprentices constructed a dramatic 33-foot-high cake at the Trocadéro gardens.

See also france and pastry schools.

licorice, or liquorice, refers both to the leguminous plant (Glycyrrhiza glabra), especially its root, and to confections made from it. Its Latin name, meaning “sweet root,” was given by the first-century herbalist Dioscorides. Although many other spices and herbs are compared to licorice, including anise, star anise, fennel, and chervil, its flavor is quite distinct and usually much stronger. The fresh or dried roots can be chewed directly as a kind of breath freshener and tooth cleanser, a practice common in Jamaica and elsewhere. Normally, however, the roots are chopped and boiled in water; the resulting sweet, aromatic liquid is reduced and dried into a flat, hard sheet, which is either broken up or scored into small chips. This is true licorice in its purest form, without added sugar. Versions like this, or molded into sticks, lozenges, or drops, are still common in Southern Europe, the most highly regarded coming from Calabria and Spain. Throughout Italy one can find hard, pure licorice made by companies such as De Rosa, Amarelli, or the popular Tabu, which has other flavors added, including mint. Sen-Sen, once popular in the United States as a breath freshener, is similar, though it too contains other flavorings.

Licorice was long considered a medicinal plant, taken as a diuretic and expectorant and mixed into other medicines as a flavoring. As the original medicinal uses proliferated, they gradually encouraged popular consumption for pleasure. John French’s The Art of Distillation (1651) provides a good example of how medicinal drugs become recreational. His recipe for Usque-bath or Irish aqua vitae is made with alcohol, sherry, raisins, dates, cinnamon, nutmeg, and “the best English licorish Sliced, and bruised.” He explains that this preparation is commonly used in surfeits as a remedy for the stomach, but the pleasant flavor certainly commended it for any occasion.

During the twentieth century these medicinal associations were lost, and licorice is now mostly eaten as candy, although some modern medicinal uses still exist for substances derived from it. The active ingredient called glycyrrhiza has various negative side effects, so it is often removed from licorice-based medicines. In this form it is used to treat peptic ulcers as well as coughs and asthma. Some studies have shown that licorice also raises the blood pressure; others have connected licorice to lower testosterone levels in men. Licorice (gan cao) has played a major role in traditional Chinese medicine for a wide variety of ailments, especially those causing bodily inflammation.

Candy made from licorice usually includes sugar, cornstarch, gum arabic, or gelatin as a binder and to make it chewy. Ralph Thickness, in his Treatise on Foreign Vegetables (1749), provides several detailed recipes for licorice confections. Most include some form of starch, powdered sugar, and gum, as well as flavorings such as orange flower water. See flower waters. His recipe for Liquorice Juice of Blois can still be followed today. Despite the name, it produces a solid candy:

Take of Gum Arabick grossly pounded iv lb. Sugar iii lb. Liquorice, dried scraped and bruised ii lb. Infuse the Liquorice for twenty-four Hours in xxx lb. of water. Divide the strained Liqor into three Parts, in two of which dissolve the Gum Arabick over a slow fire, and pass it through a Hair-Sieve; then boil it with the remaining part of the Liquor to the consistence of a Plaister, adding the sugar toward the end, and stirring continually to make it white.

In the Netherlands, where licorice is highly popular, salt is traditionally added to “drop” or coin-shaped candies. Other shapes include Katjes Katzenpfötchen (little cat’s paws). Germany’s Haribo company produces colorful, unsalted Lakritzkonfekt. See haribo. In England the Pomfret or Pontefract Cake is a similar confection. Ammonium chloride is added to a version in Finland called salmiakki, which gives it a distinct alkaline flavor. These candies can also be used to flavor distilled spirits.

In the United States, licorice usually refers to a twisted stick of chewy candy, a long lace or whips, all of which are manufactured industrially. These might be black licorice, or strangely red, containing no actual licorice but artificially flavored to taste vaguely like strawberry. Twizzlers and Red Vines are the two best-known producers of this kind of licorice, though other companies have produced a wide range of flavors. Thus, licorice has become a generic candy type, as opposed to a particular flavor, in the United States.

There are also a wide range of confections flavored with licorice, such as small, candy-coated pellets; brightly colored pink, yellow, and blue layer-cake-like squares; soft black and white drops; and other curious shapes. These forms mixed together are known as “allsorts,” the most renowned producer of which is Basset’s in Sheffield, England.

Another iconic licorice-flavored confection are the small, candy-coated pellets known as Good and Plenty, which were once vigorously advertised on TV with the figure of Choo-Choo Charlie. This candy, like most licorice candies, has dropped dramatically in popularity in the United States. Once common candies such as crows, black jack, and plain black licorice whips are increasingly difficult to find.

See also children’s candy; starch; and tragacanth.

Life Savers originated in 1912 when Clarence Crane, head of the Queen Victoria Chocolate Company, created a mint that would not melt like chocolate in the humid Cleveland, Ohio, summer. His Pep O Mint flavored candy with a center hole looked like a miniature life preserver. (Ironically, his son, the Romantic poet Hart Crane, leapt to his death without a life preserver in the Gulf of Mexico 20 years later.)

By then, the Life Saver formula had been sold to brothers Robert and Edward Noble of Greenwich, Connecticut, who packaged them in a foil tube. Candies with new flavors of Orange, Lemon, and Lime were crystalline rather than opaque. Other early flavors included WintOgreen, CinnOmon, ClOve, LicOrice, ChocOlate, MaltOmilk, CrystOmint, Anise, Butter Rum, Cola, and Root Beer. In 1935 the Five Flavor roll was introduced, containing Pineapple, Orange, Cherry, Lemon, and Lime candies.

During World War II, other candy companies donated sugar rations to the Life Savers Corporation, enabling the production of millions of candy boxes to pack into field ration kits as a reminder of home. “Life Saver Sweet Story” books, 10 rolls in a cardboard book-shaped box, became collectible Christmas treats. The candy rolled out in New York and Ontario, Canada, until a merger with Beech-Nut in 1956 moved production to Canajoharie, New York.

Kraft Foods bought the company in 2000 and production returned to Canada. The Wrigley Company purchased Life Savers in 2004, adding Pops, Gummies, Shapes, Hawaiian Fruits, and Fruit Tarts to the Life Savers brand. More than 40 flavors have been introduced in the candy’s 100-plus-year history, among them Piña Colada, Tangerine, and Musk in Australia. The Life Savers Five Flavors, now Pineapple, Orange, Cherry, Raspberry, and Watermelon, are most often found in a bag or bulk pack of 20 rolls.

See also candy packaging and hard candy.

Lindt, Rodolphe (1855–1909), improved the smoothness and melting quality of Swiss chocolate by devising a revolutionary method called “conching,” whereby extra cocoa butter is kneaded into the chocolate mixture during the manufacturing process. The Lindt brand, over time, has attained almost iconic status: “Whenever I am driving from Switzerland to Austria … a few miles south of the city of Zurich [near the Lindt & Sprüngli factory in Kilchberg], I slow down, lower the car window … and inhale deeply and happily, because the air is always delightfully charged with the fragrance of chocolate.” So wrote Joseph Wechsberg in the 19 October 1957 issue of The New Yorker magazine.

Rodolphe Lindt was born in Bern, Switzerland, into the family of a pharmacist politician. After training as an apothecary, he founded his own chocolate factory in Bern in 1879. At that time, chocolate was essentially just a mixture of cocoa solids and sugar, which tasted somewhat coarse and dry. To improve the texture, Lindt added extra cocoa butter to the mixture and invented a “conche” machine, with a long, heated stone trough, curved at each end and named for its resemblance to a conch shell. The machine was fitted with a roller to work the chocolate mass back and forth at a temperature of 131° to 185°F (55° to 85°C). Stone conches are still used today, in addition to modern rotary conches that knead the mass intensively. Conching may take from several hours to a week, depending on the quality desired. It improves the finished product’s flavor and enables it to melt easily on the tongue.

In 1899 Lindt joined forces with Rudolf Sprüngli, who had built a chocolate manufacturing plant in Kilchberg, outside of Zurich. The facility is still used as one of the company’s European production sites.

See also chocolate, luxury and switzerland.

Linzer Torte, replete with spices and fruit, has for more than 300 years been the culinary representative of the provincial city of Linz on the Danube River in Upper Austria. Nineteenth-century travel books have two recurring themes in connection with Linz: Schöne Linzerin, beautiful Linz woman, and Linzer Torte. The beauty of the women of Linz was emphasized by their elegant traditional costume, including a precious golden bonnet. However, it is doubtful that they actually wore this costume for baking, as was depicted on the cover of one of the oldest Linz cookery books, published in 1846.

Linzer Torte is the oldest torte with a geographical designation. See torte. It developed over time from the multitude of exquisite almond cakes that were popular in Austria during the baroque period and eventually become well known throughout Europe, spreading along the trade routes that intersected Linz on the Danube in all directions. To this day, Linzer Torte is regarded as a traditional Christmas cake in Baden-Württemberg in southwest Germany. In Vienna, Linzer Torte was the most popular cake until the invention of Sachertorte. See sachertorte. Emigrants took the popular cake to all continents. As early as 1855, Linzer Torte was well known in Milwaukee, thanks to the Austrian musician, painter, and poet Franz Hölzlhuber (1826–1898), who earned his living by baking Linzer Torte during a period of economic hardship. A century later other prominent émigrés, the von Trapp family of Sound of Music fame, spread Linzer Torte’s reputation to Stowe, Vermont.

The earliest known recipes for Linzer Torte are found in the 1653 cookery manuscript of Countess Anna Margarita Sagramosa, now in the Stiftsbibliothek Admont in Styria, Austria. At that time Linzer Torte was served in the form of a Schüsseltorte (dished torte), which was essentially a sweet pie filled with stewed fruit. See pie. The first printed recipe was published in 1718 in Augsburg as part of the famous Neues Saltzburgisches Koch-Buch by Conrad Hagger, who proposed the “good and sweet Lintzer-dough” for the torte. Today, the largest collection of historical Linzer Torte recipes may be found at the Upper Austrian provincial museum (Oberösterreichisches Landesmuseum) in Linz, but many Upper Austrian families guard their own traditional recipe, and each torte tastes a little different.

Owing to its expensive ingredients, Linzer Torte remained a status symbol well into the nineteenth century, especially when served to guests. Almonds and lemon zest, fresh butter, precious cane sugar, and the finest white flour were used for the dough, which was refined with prized spices like cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, and cardamom. The earliest fillings consisted of desirable fruit such as quince and peach. Later, as spices were added in larger quantities and threatened to dominate the sweet quince aroma, tart red fruits were used instead, including red currants, cherries, and raspberries.

The torte’s characteristic lattice decoration is mentioned from the start. Copperplates in Hagger’s cookery book illustrate lattice toppings as impressive works of art, rolled or cut from the dough or applied by piping. However, not all early Linzer Tortes looked alike. Some were multilayered, filled with various fruits, and garnished with colored icing and candied fruit. See candied fruit and icing. Others featured an especially decorative spiral pattern. These variations in taste and appearance reflected the baroque sensibility.

Today, Linzer Tortes tend to be uniform in appearance. The classic Linzer Torte is now unthinkable without a lattice top, often decorated with slivered almonds. However, almonds have disappeared from the dough, replaced by hazelnuts, and occasionally walnuts. Combined with the spices, these nuts yield a darker dough; hence, the term “dark Linzer Torte” in contrast to the “light Linzer dough” made with almonds. In either case, the dough can be worked like a short crust or made using eggs and beaten until fluffy. See shortbread. Cinnamon, cloves, and red currant jam are generally used for the filling. The torte should be allowed to mature for a few days after baking for its fine taste to develop.

The light Linzer dough with almonds and lemon forms the base for a number of smaller pastries categorized as “Linzer Bäckerei” (baked goods), including Linzer Augen (eyes) and Linzer Kipferl (crescents), both filled with tart red currants. The simplest forms of Linzer Bäckerei are rolled cookies in the shapes of little stars, moons, rings, and so on. See rolled cookies. It is also possible to shape softer dough into Linzer Stangerl (little bars) and Linzer Krapferl (tartlets). All of these cookies, which are ubiquitous in Austrian pastry shops, may be filled with jam, coated with chocolate, and decorated with nuts and frosting. Linzer Torte’s offsprings also include the popular Linzer Schnitten and Linzer Weichseltorte.

See also austria-hungary.

liqueurs, including cordials and ratafias, represents a broad category of alcoholic beverages. Although they can be consumed neat or in cocktails, they are also called for in a range of cake and dessert recipes.

David A. Embury, in the 1958 third edition of his classic text The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks, devoted an entire chapter to the different types of liqueurs available and how to use them. Today, according to the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States, liqueurs outsell several other major spirits in America, including single-malt Scotch, bourbon, gin, tequila, and cognac. Liqueurs encompass alcohol produced from a wide range of ingredients and made all over the world.

The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), which regulates the labeling and taxation of the spirits industry, uses the terms “liqueurs” and “cordials” interchangeably and makes no distinction between the two. The TTB’s definition for the overall category centers on a few key points. A liqueur is a flavored spirit that must include at least 2.5 percent sugar by weight. The base can be any kind of spirit, and it can be mixed or redistilled with all sorts of fruits, flowers, plants, juices, or other natural flavorings and extracts made from infusions or macerations. The U.S. government has also set definitions for liqueur subcategories, such as sloe gin, sambuca, kümmel, triple sec, and ouzo.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the first use of the word “liqueur,” which comes from the French word liquor, occurred in 1742. Other sources suggest that it stems from the Latin word liquefacere, which means “to melt.” The origins of “cordial” date back even further, to the late 1300s. The root of the word can be traced to the Latin word cor, which means “heart.” Cordial originally referred to an invigorating drink that was comforting or exhilarating.

To confuse things even further, there are also ratafias to contend with. Jerry Thomas, a pioneering bartender in the 1800s, lists more than a dozen recipes for ratafias—flavored with everything from cherries to black currants to green-walnut shells to angelica seed—in the appendix of his seminal book How to Mix Drinks, or The Bon Vivant’s Companion (1862). He starts off the section by stating that “every liqueur made by infusions is called ratafia; that is, when the spirit is made to imbibe thoroughly the aromatic flavor and color of the fruit steeped in it; when this has taken place the liquor is drawn off, and sugar added to it; it is then filtered and bottled.” The earliest ratafias were made by crushing peach, cherry, apricot, or bitter almond kernels and infusing them in brandy or spirits for a few months; the kernels were then strained out and the alcohol sweetened. Later versions mixed juice pressed from fruits such as cherries, blackberries, and grapes with brandy and sugar and left the mixture to age—a safer process, as it eliminated any risk of cyanide poisoning from the kernels. The OED’s definition of “ratafia” is shorter but essentially the same as Jerry Thomas’s, with the first reference dating back to 1670 from a print in the collection of the British Museum. And the dictionary adds another layer: “ratafia” also refers to a sweet French aperitif made from an aged mix of brandy and grape juice. It can also mean a cake or biscuit flavored with the liquor. Although the majority of people generally use the more general terms “liqueur” or “cordial,” “ratafia” occasionally still shows up on menus and in cookbooks. The TTB, however, does not recognize it as a separate category.

Liqueurs can be divided into a few main categories. Many herbal liqueurs were originally created by alchemists or monks and were thought of as remedies for common ailments. They were used to sweeten bitter drugs such as quinine; however, today’s products containing quinine are usually aperitif wines, not liqueurs. Spirits were originally used as the base since they could preserve the herbs, spices, and extracts—one reason why some believed that alcohol was the water of life. (The names “whiskey” and “eau-de-vie” originated as terms for the supposed “water of life.”) The recipes for these elixirs were often secret and guarded carefully. To this day, only two people know the complete formula for green Chartreuse, which is made by French monks and calls for 130 different herbs and plants.

Other liqueurs are floral-flavored, like Crème de Violette, necessary for the delicious (and classic) gin-based Aviation cocktail. And a tremendous variety of fruit liqueurs exist—from best-selling triple sec and curaçao, both flavored with oranges, to cherry liqueurs like the Danish Cherry Heering, a key ingredient in the Singapore Sling. There is even Luxardo Maraschino Liqueur, which is distilled from Italian marasca sour cherries and aged in Finnish ash-wood vats.

Some brands use nuts, like the Italian hazelnut-flavored Frangelico that dates back to the 1700s. It is based on an elixir made by monks living in Piedmont. Cream versions are also an option, such as Baileys Irish Cream, one of the best-selling liqueurs in the world that calls for Irish whiskey. Coffee-and-rum-based varieties include Kahlúa and Tia Maria.

The category of liqueurs is certainly diverse, partially because many families traditionally produced their own liqueurs; a number of brands, like the Italian amaretto Disaronno, started out as personal recipes. Not that long ago liqueurs had a much larger mixological profile than they do today. In the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, liquor cabinets were filled with bottles of elixirs like Drambuie, a mix of Scotch, Scottish honey, spices, and herbs and the key ingredient in the classic Rusty Nail (one part Drambuie, one part Scotch). Harvey Wallbangers and Golden Cadillacs powered the 1970s nightlife scene, and both recipes require the sweet Italian liqueur Galliano, which is made from a secret recipe calling for 30 spices, herbs, and plant extracts. Galliano was also the secret ingredient in the Harvey Wallbanger cake, a Bundt cake as trendy in the 1970s as its namesake drink. But the granddaddy of all liqueur-centric drinks is the Pousse-Café, made by layering different liqueurs by their densities so that they do not mix. The finished product looks like an impressive—and colorful—slice of layer cake.

These concoctions were so popular that David A. Embury included this cautionary note in The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks (first published in 1948): “You probably would not try to eat a five-pound box of chocolates before dinner as an appetizer, and if you did try it you would probably get thoroughly sick. For precisely the same reason (only more so) you should not try to consume several cocktails whose principal ingredient is a conglomeration of heavy-bodied, high-proof, syrupy liqueurs.”

His advice, on both ends, still holds up today.

Over the last few years, thanks to the rebirth of the cocktail and bartenders unearthing vintage recipes, interest in liqueurs has grown. But the learning curve is steep, since the current generation of bartenders and drinkers needs to be taught how to drink liqueurs and how to use them properly in cocktails. However, herbal liqueurs have certainly caught on. The bitter Italian Fernet-Branca has been embraced around the country by bartenders, who pour each other shots of the liqueur as a professional courtesy.

Importers both large and small are now flooding the U.S. market with products from across the globe, like the complex herbal Zwack Unicum from Hungary and the artichoke-based Cynar from Italy. And old favorites, such as the orange-and-cognac Grand Marnier and the citrus-and-brandy Tuaca, are making a play for new drinkers who might not have tasted their products before. These brands are sponsoring bartending contests and hiring celebrity ambassadors.

A number of new liqueurs have recently been created. The most popular (and easiest to find in the United States) is St-Germain, an elderflower-flavored liqueur produced in France and packaged in what looks like a jumbo belle époque perfume bottle. The concoction can be mixed with virtually any spirit and even dry white wine, which has made it ubiquitous in cocktail bars over the last few years. (It has done so well that rum giant Bacardi purchased the brand from its founder, Robert Cooper, in early 2013 for an undisclosed sum.) Another successful launch has been the French Domaine de Canton, a sweet ginger liqueur.

Even though many liqueurs hail from Europe, you need not travel far to find them. A number of craft distilleries across the United States, such as Clear Creek Distillery in Portland, Oregon, are making liqueurs from local ingredients; Clear Creek produces seven different bottlings, including cranberry, blackberry, loganberry, and cassis.

See also medicinal uses of sugar.

literature, in its representation of sweets, presents a wide range of meanings, both positive and negative. Sweets appear in almost every form of imaginative writing from the Hindu Vedas onward. When sweets grace the table, they also grace the page. A society that develops a culture of sweets tends to both portray and examine that culture in its literature, both in the sense of celebrating the variety and frequency of sweet dishes, and in the depth of meaning that sweets carry in that literature. Sweets and sweetness are remarkably pliable, employed to illustrate notions of eroticism, aesthetics, innocence, immaturity, comfort, luxury, satire, disgust, and the uses of power, to name a few. Throughout history, the literature of sweetness has featured prominently in societies that brought confection to high levels of artistry, especially ancient India, where sugar refining was invented; the medieval Arab lands, which brought the art of sugar to new heights; late medieval and Renaissance Europe, which elaborated upon the mystical ramifications of sweetness; and the post-industrial Western world, in which sugar’s declining expense brought it into every household.

Ancient and Classical Literature

The early history of sweets in literature is hardly distinguishable from the early history of sweets themselves, since much of our knowledge about ancient confectionery derives from imaginative writing. The first references to sweets appear in the Hindu Vedas (ca. 2000–800 b.c.e.). See hinduism. The Rig Veda describes the ancient Aryans as driving their chariots “while drinking honey, listening to the beautiful humming of the bees, with their chariots also humming like bees, drinking milk laced with honey.” Cane sugar appears first in the Atharva Veda, used as a metaphor for love: the lover offers to enclose his beloved in a ring of sugarcane to both protect and entrap her. Specific sweets figure prominently in the Hindu epic Ramayana; for instance, Rama and the other princes of the narrative are conceived after their mothers eat magic portions of kheer, or rice pudding. Ganesh, the elephant god who was the legendary writer of the other major epic of the subcontinent, the Mahabharata, is associated with a gluttonous passion for modaka, a sweet dumpling still made during ceremonies to worship him. Numerous references to sweets occur throughout ancient Indian literature. See india and modaka.

Although less prominent than in South Asia, sweets also feature in early East Asian literature. “Fried honey-cakes of rice flour and malt-sugar sweetmeats” appear in the third century b.c.e. Chinese poem “The Summons of the Soul” as an enticement for a lost soul to return to its body. More metaphorically, the “The Filial Piety Sutra” (ca. 589–906 c.e.), a key text of Mahayana Buddhism, describes the mother’s “kindness of eating the bitter herself and saving the sweet for the child.” See buddhism; china; east asia; and south asia. Honey-based sweets also figure somewhat in Ancient Greek and Roman literature (sugar was too rare for regular use) as luxurious comestibles. See ancient world and honey. In the climax of Aristophanes’s allegorical play Knights, the demagogue Cleon withholds most of a plakous (a cake) from the Athenian people and loses their love. See placenta. In Plato’s Republic, Socrates approvingly notes the fact that the warriors of the Iliad abstain from sweets. Greco-Roman literature does make significant use of “sweet” (in Greek, gluku; in Latin, dulcis or suavis) as a rhetorical term, imbuing it with a range of aesthetic and emotional meanings. Sappho famously uses the term glukupikron, sweet-bitter, to describe the paradoxical intensity of erotic love, while Martial contrasts his “salty” satires with the sickly sweet poems of his rivals.

Medieval and Early Modern Literature

Medieval Arabic literature, which, like ancient Indian literature, was written in the shadow of sugarcane, is positively obsessed with sweets and sweetness. In one tradition collected in the Ḥadīth, even the prophet Muhammad sighs over fālūdhaj, a dish made of wheat, honey, and clarified butter, though the meaning of that sigh was roundly debated. See islam; middle east; and persia. Several stories in 1001 Nights revolve around sweets, such as the battle between a husband and wife over a kunafāh (a fried pancake at that time) sweetened with cheap molasses instead of honey. Although satirists in every age use lowly food as a way of deflating noble abstractions and exposing pretensions, Arab satirists employ sweets with unusual abandon. The fifteenth-century satirical poet Ibn Sūdūn continually mentions bananas with honey and sugar syrup, about which he waxes, “My heart is madly in love since it misses you.”

Following the lead of the Greeks and Romans, medieval European authors elevated sweetness to a term of indispensable poetic, religious, and social efficacy. “No word is used more often in the Middle Ages,” writes Mary Carruthers, “to make a positive judgment about the effects of works of art” (2006, p. 999). Meanwhile, in Italian literature, the dolce stil novo, or “sweet new style,” of Dante, Cavalcanti, and other poets heralded a new focus on courtly love and rhetorical artistry; it became one of the most influential literary movements in medieval Europe. Petrarch’s Rime Sparse extended the power of sweetness by establishing it as a primary term for describing the complex experience of love, both earthly and divine.

Renaissance authors continued to concern themselves with the role of sweetness in aesthetic, erotic, and other kinds of social experience, but with new intensity, as cane sugar began to enter the consumer market in larger quantities and to take a major role in imperialist conquest. See sugar trade. When Frances Meres referred to his contemporary as the “honey-tongued” Shakespeare with his “sugared sonnets,” he was drawing attention to the subtlety and erotic content of Shakespeare’s poems. Shakespeare’s plays also use sweetness in a variety of ways. “Sweet Valentine,” calls Proteus in The Two Gentlemen of Verona, in a display of intense male friendship and (perhaps sexually charged) affection. “Sweets to the sweet,” mourns Hamlet’s Gertrude as she scatters flowers over Ophelia’s grave. In Antony and Cleopatra, Antony worries that all his former allies “do discandy, and melt their sweets / On blossoming Caesar” after Cleopatra’s betrayal during the Battle of Actium. (The term “candy” entered English during the sixteenth century from Italian; “discandy” seems to be Shakespeare’s invention.)

Starting in the seventeenth century, when chocolate and ever-cheaper sugar arrived in Europe, literature was more saturated with specific sweets, while the term “sweetness” grew so universal as to become essentially generic. Now available in large numbers to the middle and lower classes, sweets took on new meanings while retaining the older sense of luxury. In England, puddings, simple but rich, seem especially freighted in this regard, as evidenced by the Christmas pudding, “like a speckled cannon-ball,” that caps the holiday meal in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, and which Bob Cratchit regards “as the greatest success achieved by Mrs. Cratchit since their marriage.” See pudding. But increasingly, sweets exhibit a dark side, evoking decay, mortality, and power, as in the quietly sadistic Guy de Maupassant story “The Cake,” where being the cake cutter at a party is transformed from high honor to awful burden. The Industrial Revolution’s increasing infatuation with and unease about rampant consumption (of not only sugar but also commodities more generally) no doubt play a significant role in this change of emphasis.

Modern and Contemporary Literature