dacquoise is a confection that looks like a cake but consists of two or three layers of hazelnut- or almond-flavored cooked meringue with a filling sandwiched between each layer. See meringue. Buttercream is traditional, but fruit fillings and whipped cream are also commonly used. A dusting of confectioner’s sugar may cover the top and sides of the dacquoise, or it may be spread with buttercream or left bare to show the beautiful layering of meringue circles and filling. A dacquoise can be made large, like a cake, or small, for individual desserts. Julia Child writes in Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1979, Vol. 2) that a great deal of disagreement exists in French cookbooks on what the layers should be filled with, and “since no one agrees on anything, you are quite safe in doing whatever you wish.” This elegant dessert is found in pastry shops all over Paris, where it may be called a Succès or a Progrès. According to Child, the difference depends on whether ground almonds are used in the meringue or a mixture of almonds and hazelnuts. However, even this rule is not hard and fast. Older French cookbooks typically use one of these names instead of “dacquoise,” regardless of the cake’s composition. In his Gastronomie pratique (1928), Ali-Bab simply calls the confection a gâteau meringué (meringue cake) and recommends that it be filled with any sort of flavored cream, such as pistachio, chocolate, or mocha.

See butter; buttermilk; cheese, fresh; cream; evaporated milk; milk; sour cream; sweetened condensed milk; and yogurt.

Dairy Queen, officially the American Dairy Queen Corporation, or DQ as it is known to its franchisers and fans, is one of the largest fast-food systems in the world today.

The company originated when John Fremont “Grandpa” McCullough and his son Alex operated the Homemade Ice Cream Company in Davenport, Iowa, in 1927. In the early 1930s, they moved their ice cream production into a former cheese factory in Green River, Illinois. The senior McCullough understood that ice cream served as a frozen solid at 5°F (–15°C) numbed the taste buds, and that it tasted more flavorful when soft. By experimenting, he discovered that fresh ice cream dispensed in a semi-frozen, custard-like state at about 23°F (–5°C) had the best flavor. The problem was that in the 1930s no equipment was available for dispensing semi-frozen ice cream that would also keep its shape. See ice cream.

Despite these technical problems, McCullough continued to work on the development of a soft-serve frozen dairy product. In 1938 he was ready to test his idea on the public. The McCulloughs asked Sherb Noble, a good friend and customer, to run an “All You Can Eat for 10 cents” trial sale at his walk-in ice cream store in Kankakee, Illinois. The men made ice cream and scooped it into cups while it was still soft. Within two hours on 4 August 1938, 1,600 servings of this new dessert were served.

As a result of the 1973 oil crisis, the state of Oregon banned neon and commercial lighting displays. Some businesses, like this Dairy Queen in Portland, Oregon, used their unlit signs to convey energy-saving messages that could be seen during the day. photograph by david falconer / u.s. national archives

Encouraged by the public’s response, McCullough asked two manufacturers of dairy equipment to design and produce a machine that would dispense semi-frozen ice cream. Neither was interested. By chance, he read in the Chicago Tribune that Harry M. Oltz, who operated a hamburger stand in Hammond, Indiana, had patented a continuous freezer that would dispense soft ice cream. The men partnered in 1939, with the McCulloughs having exclusive use of the freezer west of the Mississippi River and Oltz having control to the river’s east. Oltz moved to Miami, Florida, and established AR-TIK Systems, Inc. to promote soft-serve ice cream.

In 1940 Noble opened the first Dairy Queen store in Joliet, Illinois, under license from McCullough, who also created the Dairy Queen name. He grossed a whopping $4,000 in revenue that first season. In 2011 the Joliet City Council granted local landmark status to the nondescript whitewashed building on historic Route 66, where the first Dairy Queen cones were sold for 5 cents.

By the end of 1942, eight Dairy Queen businesses were in operation. Since manufacturing materials were devoted to the war effort, no new freezers could be built. During World War II, the McCulloughs kept busy developing their new franchise business and negotiating territories. Grandpa McCullough wrote many of these agreements on the back of napkins and paper sacks, an informal and haphazard procedure that would later cause untold problems for the company and the courts. Fast-food franchises were new at this time, although other entrepreneurs such as Howard Johnson had embraced the concept successfully in the 1930s.

In 1941 the McCulloughs opened another store in Moline, Illinois. It was this rectangular box store with its glass front, flat roof extended over the service window, and large sign featuring an ice cream cone with a curl that became the prototype for postwar expansion. “Curly” became the Dairy Queen soft-serve mascot; in the 1960s the ice cream cone sign was replaced with the more modernistic “red kiss.”

Impressed by the long lines outside Dairy Queen shops, Harry Axene, a sales manager for a farm equipment company, approached Grandpa McCullough and negotiated a 50–50 partnership. In 1946 Axene called together all 17 Dairy Queen operators to form an organization to standardize operating procedures and to expand the company. By the end of 1948, 35 store owners came together to create the Dairy Queen National Trade Association. By 1950, 1,400 stores were serving a limited menu of sundaes and cones for immediate consumption, and pints and quarts to take home. Axene cut his ties with the company in 1949 and established the Tastee Freeze Company on the West Coast. In the 1960s, Dairy Queen purchased the franchise rights of Harry Oltz’s AR-TIK Systems.

Dairy Queen opened its first store in Tokyo in 1972, and by 1976 there were 150 stores in Iceland, Guatemala, Trinidad, Panama, Hong Kong, and several other countries. The company also added new products. One major success was the Blizzard, a soft-serve concoction of ice cream blended with candy, cookies, and fruit. In the 1980s, the company purchased Golden Skillet, a fried-chicken chain; Karmelkorn Shoppes, Inc., a popcorn and candy franchise; and Orange Julius, a fruit-flavored blended drink and snack operation. See orange julius.

In 1997 Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Inc. of Omaha, Nebraska, purchased DQ for $585 million in stock and cash. The company now operates more than 6,000 restaurants in the United States, Canada, and 18 other countries.

See also baskin-robbins; ben & jerry’s; eskimo pie; and häagen-dazs.

dango are Japanese dumplings made from a dough formed into a ball and steamed. Although plain dango have been eaten in Japan since at least the eighth century, the customary practice of serving four dango as a sweet—on a skewer topped with sweetened soy sauce, azuki bean paste (an), or soybean flour (kinako)—developed in the early modern period (1600–1868) as an inexpensive treat sold by vendors. Dango can also be shaped into flat circles and boiled or grilled.

Dango are similar to mochi, but the latter are usually created from glutinous rice or other whole grains, whereas dango are traditionally made from nonglutinous rice flour, which gives them a chewy consistency like gnocchi. See mochi. As is characteristic of Japanese sweets, many seasonal varieties of dango exist. Moon Viewing (tsukimi) Dango are prepared in the autumn; Flower Viewing (hanami) Dango are snacks in cherry blossom season, giving rise to the saying “preferring dumplings to flowers,” which indicates that the refreshments served at flower viewing parties often overshadow the beauty of the blossoms. Rice flour dango are preferred as confections, but savory dango made from wheat, buckwheat, and millet were staple foods before World War II. Farmers stuffed dango with vegetables flavored with miso and grilled plain dumplings for a quick meal. Dango can also be added to a clear or miso soup or to a sweet azuki bean soup called shiruko. See azuki beans. In some regions, dango were made from potatoes, nuts, or ground sesame.

See also japan.

See laminated doughs.

dariole dates to medieval Europe and has never left the French dessert repertoire, although it is considered old-fashioned now. It is a small tart with a pastry shell and a flavored milk and egg custard filling. The flavorings include butter and sugar and a “perfume,” such as rosewater, vanilla, cinnamon, or orange flower water. Some texts, such as Le ménagier de Paris (1393), give no recipe but simply list darioles on menus appropriate for weddings. Other texts, including Le viandier of Taillevent (published 1486) and early English manuscripts, have somewhat mangled instructions for making darioles. The Italian cook Martino (ca. 1465) offered a recipe for a single large custard tart called a dariola. The anonymous author of Le pâtissier françois (1655) includes a detailed dariole recipe that is for a single large tart made in a pastry-lined tourtière. By the eighteenth century, darioles were small custard tarts made in molds with fluted sides, and the word “dariole” now principally refers to this kind of mold. According to Larousse gastronomique (1938), dariole molds lined with puff pastry can be filled with frangipane, flavored with a liqueur, and sprinkled with powdered sugar after baking. See frangipane. In Le livre de pâtisserie (1873), Jules Gouffé flavors the custard with vanilla sugar, citron, orange, orange flower water, and crushed macaroons. Dariole does not appear in Julia Child’s classic Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1961).

See also cream pie; custard; and flower waters.

dates are the fruit of the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera), a tree native to the deserts of North Africa and the Middle East. There are well over a thousand varieties of dates, ranging from dry and fibrous “camel dates” to moist and sweet medjools with their distinctive caramel-molasses flavor. They can be consumed in many stages, including the underripe khalal phase (crunchy and a bit astringent), the fully ripe rutab phase (moist and easy to spoil), and the tamr phase (wrinkled, less moist, and nonperishable) when most of the fruit are sold.

Date palms were probably first domesticated at least 5,000 years ago along the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. The trees favor intense heat and abundant below-ground water, making them a perfect cultivar for desert oases. Energy-filled and rich in nutrients, dates became culinary staples in desert cultures from northern India to Morocco. Appearing in many myths and religious accounts, date palms were often portrayed as the original “tree of life.” Dates were a favorite food of Muhammad, who liked to eat them with cucumbers. Today, many Muslims break their Ramadan fast with a meal of dates. See islam and ramadan. They are a common ingredient in many North African and Middle Eastern sweets, such as the date-filled cookie called maʾamoul. Date syrup, known as rub or dibs in Arabic, is used much like molasses as a sweetener. In Morocco, whole dates are frequently cooked in tajines with lamb or other meats.

Although the only large-scale date palm groves in Europe are found in the city of Elche in southeastern Spain, dates have been known for centuries in Western Europe. In medieval medicine, they were often eaten to “strengthen the womb” and to treat diarrhea and other stomach disorders. During the nineteenth century, dates became popular as sweet treats, either whole or as ingredients in dishes like date puddings. Today, sticky toffee pudding made with dates is a popular British dessert. See sticky toffee pudding.

Around 1765 a Spanish priest in Baja California planted the first date palms in the New World. Anxious to develop the arid regions of the America Southwest, the U.S. Department of Agriculture began importing date palms to southern Arizona and California in the late nineteenth century. From about 1910 on, the American date industry took root in California’s Coachella Valley, about 20 miles southeast of Palm Springs, where summer temperatures can reach 120°F (49°C). The region’s early date farmers concentrated on palms producing the deglet noor (in Arabic, the “date of light”), which is still the most common variety found in American supermarkets. Picked straight from the tree, deglet noors have a delicate, honey-like flavor. For commercial use, however, most deglet noors are usually dried for storage and then rehydrated with steam (which cuts the flavor) and pitted just before packing. The fruit soon became a popular ingredient for many baked goods, including date and walnut breads; various pies, puddings, and cakes; and even salads made with dates and other fruit. Many Coachella Valley date farms built roadside stands to sell their product to travelers. To cool off, visitors could also enjoy a date shake made from chopped dates, milk, and ice cream.

In 1927 a USDA botanist named Walter Swingle imported the first offshoots of the medjool date palm to the United States. Large, moist, and full-flavored, medjools were considered one of the premier date varieties. They were native to Morocco and Algeria, where a soil fungus had devastated the medjool orchards, but Swingle managed to find a few healthy offshoots in an isolated Moroccan oasis. In the 1940s the first medjool offshoots were released to commercial farmers in California and southwestern Arizona. When the trees finally bore fruit, medjools were recognized as the finest American-grown date. Beyond a small group of date fanciers, however, they never caught on with the broader American public. (In fact, the current American per capita consumption of dates is less than 6 ounces a year.) In recent decades, American medjools have found a market among immigrants from countries in the Middle East and North Africa, where dates are part of the culinary heritage and an important ingredient for holiday feasts. The Coachella Valley has for decades been the world’s largest medjool-growing area. Based on plantings of young trees, it is projected that this region will soon be overtaken by the sprawling expanse of medjool date groves along the Colorado River near Yuma, Arizona.

Today, about 70 percent of the American date crop is deglet noors, mostly used by the baking industry. Medjools make up much of the rest; more than a third of this crop is shipped for export, mainly to Europe, Canada, and Australia. In cities with large immigrant communities, ethnic markets also sell imported medjools and various varieties from Israel, Saudi Arabia, and other Middle Eastern countries. A few Coachella Valley growers, like Oasis Date Gardens, also grow lesser-known dates such as the barhi, halawy, khadrawy, thoory, and zahidi varieties.

See also dried fruit; middle east; molasses; north africa; and palm sugar.

Day of the Dead, celebrated by Christians on 1 November, draws on much older festivities that honor the deceased. When Pope Boniface IV first proposed a celebration in tribute to the Virgin Mary and All Saints in 610 c.e., the date chosen was 13 May to coincide with Lemuria, a Roman festival dedicated to ancestors. However, this celebration of all saints did not succeed; it was only some 200 years later that the holiday finally took hold. In 835 Louis the Pious, emperor of the Carolingian Empire, declared a celebration of the Christian saints in autumn, partly in an attempt to override the widespread pagan rituals practiced at that time of year. These festivities were likely related to the Celtic harvest festival of Samhain, when the souls of the dead were said to return to their homes. In the ninth century, under Pope Gregory IV, the Catholic Church finally mandated 1 November as All Saints Day. Next came the solemn mass initiated in 990 by Odily, abbot of Cluny, to commemorate all the dead in monasteries under his authority. This practice gradually spread throughout Europe, and 2 November was eventually established as All Souls Day in a further attempt to supplant the continuing pagan celebrations in honor of the dead.

In the northern hemisphere, Day of the Dead celebrations take place at a cold and dark time of year. Documents dating back to the early Middle Ages attest to the season’s communal activities, including the late harvest. It is a time when people customarily sought to consolidate relationships through convivial rituals and liturgies before the winter set in.

In Mexico, at least two existing Aztec rituals, Miccailhuitontly, the Feast of the Young Dead, and Hueymiccailhuitl, the Feast of the Old Dead, facilitated the Catholic Church’s integration of the pagan and Christian. The date 1 November is celebrated as Day of the Dead Children, while 2 November is the Day of the Adult Dead.

Because the influence of the Catholic Church has historically been very strong in Mexico, Italy, and Spain, Day of the Dead celebrations in these countries are emblematic of the holiday. Street markets, parades, and altars saturate the senses with fragrant, sweet smells from private and public kitchens. Cooks, momentarily akin to priests, officiate in culinary votive rituals that integrate the pagan with the Christian. In Europe, pristine altars covered in white linen display sweets like quince paste, roasted chestnuts, dried fig and almond bars, walnuts, and dates. Spain offers a variety of sweets in the shape of bones—realistic edible relics—some fried (like the huesos de San Expedito), others baked, such as the huesos de Santo, bones made of marzipan and sweet potato, egg yolk, or chocolate paste.

In Mexico in 1740, Friar Francisco de Ajofrín referred to the production and selling of alfeñiques, zoomorphic and anthropomorphic miniatures made of sugar. See anthropomorphic and zoomorphic sweets. Sorrow and happiness merge in the virtual presence of the Great Dame—Death—as the dance of life is symbolically offered to the souls of the dead on baroque altars laden with sweets: decorated skulls made of sugar, amaranto (amaranth), and chocolate; pan de muerto (bread of the dead) made with flour, orange blossom water, pulque, and sugar, with its shape recalling a skull and crossbones; calabaza en tacha, made with pumpkin and azucar de piloncillo (unrefined cane sugar) syrup, and taninole (sweetened mashed pumpkin) beaten with milk. These votive sweets are accompanied by hot chocolate, pulque, mezcal, and tequila.

In the northern region of Lombardy, Italy, almond and cinnamon cakes called pane dei morti (bread of the dead) are baked for the holiday, along with fave dei morti (beans of the dead), sweetened bean-shaped cakes made of ground almonds. On the island of Sardinia, in Gilarza and Dorgali, they bake tiliccas, dough stuffed with grape paste, while in Palermo, Sicily, pupi di zucchero are offered up, mainly to children: sugar figures inspired by the puppets of the Opera dei Pupi. Nowadays, the pupi are often modeled after characters from popular culture, including Mickey Mouse and SpongeBob SquarePants. In Salemi, until the last century, pane dei difunti, bread braided in imitation of the crossed arms and hands of the deceased, was baked at home and distributed to the poor at the cemetery.

In Catalonia, Spain, small marzipan breads called panellets are popular. They are made from a paste of sweet potatoes, ground almonds, sugar, egg yolks, vanilla, and lemon peel. Chocolate, red currants, chopped hazelnuts, or pine nuts can be added before the cakes are baked in molds. In Madrid, the popular fried buñuelos de viento, stuffed with chestnut, pumpkin, or sweet potato paste, are reminders of the ethereal nature of life. They are eaten with hot chocolate along with marzipan huesos de Santo. In Extremadura to the west, Murcia in the east, and Andalucía in the south, gachas de difuntos are traditional, a sort of porridge made from the toasted flours of different grains cooked with milk or grape juice and flavored with cinnamon, aniseed, and ground cloves.

All these Day of the Dead offerings are examples of edible vanitas, intended to remind us who we are, where we come from, and where we will end up.

See also festivals; halloween; italy; mexico; and spain.

dental caries, the technical term for a cavity, describes the destructive outcome found in teeth following the bacterial-acidic attack on tooth structure. Those possessing a “sweet tooth”—a craving to eat sweet foods such as candy and pastries—are at greater risk of developing tooth decay because of its association with sugar consumption. The evidence that sugar plays a fundamental role in the development of dental caries is well documented and overwhelming. Sugar and other fermentable carbohydrates serve as a substrate for certain bacteria in dental plaque, and acid produced by this metabolic process induces the demineralization of enamel, making the tooth more vulnerable to decay.

Although the writings of Greeks, Egyptians, and Chinese document dental disease, the profession of dentistry emerged in the mid-nineteenth century as a discipline focused on treating diseases of teeth and associated supporting tissue. The understanding and treatment of dental caries first started with the tooth “worm theory,” which posited that a tooth worm buried its way through tooth structure and caused a toothache by moving around. The pain subsided once the worm became tired and required rest. The exact image of this creature was not known, but folklore aided in the concept of how it might appear. The British believed that the tooth worm resembled an eel, whereas the Germans thought the maggot-like worm was red, blue, and gray in color. The treatment for “tooth worm” consisted of tooth extractions and traditional herbal remedies. The worm hypothesis evolved into more sophisticated theories on the acid production of oral microorganisms. Specific types of oral bacteria are able to produce many by-products from sugar consumption, including several types of acid. The acidic environment then promotes the breakdown of tooth structure and eventually cavities in teeth. The greater consumer demand for conservation of teeth eventually led to the development of dental restorations.

A steady annual rise in sugar consumption from 6.3 pounds per person per year in 1882 to its highest level of 107.7 pounds per person per year in 1999 shows that the U.S. appetite for sugar is remarkable. Over a five-day period, a person in 1882 consumed the same amount of sugar that is currently found in a 12-ounce can of soda, and today we consume the same amount of sugar in a mere seven hours. In 2011 a world population of 7 billion consumed roughly 165 tons of sugar. Developing countries, principally in Asia, are considered growing markets, while sugar consumption has leveled off in developed countries.

Even with the steady increase in sugar consumption over the past several decades, there has been a decrease in dental caries, which illustrates the multifactorial nature of dental caries. The development of tooth decay depends on the interaction of primary factors and is influenced by oral environmental and personal factors. The interaction of antibodies in the saliva or the roughness of the tooth surface will determine whether the bacteria survive, as well as their ability to attach to the tooth surface; the type of food ingested, such as “sticky” food that lingers in the mouth, will enhance the likelihood of decay; the bacterial composition and quantity of plaque will affect the outcome; and the frequency of tooth exposure to cariogenic (acidic) environments will also play a role. Arguably the most recognizable oral environmental factor exerting the greatest single influence on caries (in the United States) has been water fluoridation. The inclusion of certain dietary alcohols (polyols), such as xylitol in chewing gum, supports the remineralization of tooth enamel. See xylitol. Personal factors that correlate with dental caries include oral hygiene, education, income, dental insurance coverage, and oral health literacy.

Thanks to education from parents, dental hygienists, and dentists, we can indulge in sweets while still preventing dental decay by frequent brushing, flossing, using mouth rinses, and even chewing a sugar-free gum to increase salivary flow. See chewing gum.

See also sugar and health.

dessert, in the sense of a sweet, concluding course to a meal, is a French custom that developed slowly over several hundred years, reaching its current form only in the twentieth century. Even now, the practice of serving a final pastry or confectionery course is neither ubiquitous nor universal, even in France. Most cultures do not finish their meals on a sweet note, and even when they do, it is often no more than with a piece of fruit. In Renaissance Italy, sweet dishes were commonly interspersed with savory, as they were in Ottoman Turkey. Even the French make exceptions, occasionally starting a meal with melon or inserting a sorbet course between two savory dishes. Many cultures eat certain meals where sweets predominate. See sweet meals. Nonetheless, with the growth of a globalized restaurant culture, the habit of finishing lunch or dinner with a sweet prepared dish is now familiar to everyone who can afford the bill.

Early Forms

The term “dessert” comes from the French verb desservir, meaning “to clear the table.” It is mentioned as the penultimate course in two menus from the fourteenth-century Ménagier de Paris, in one case consisting of venison and frumenty (a sort of pudding), and in the other of a preserve (presumably made with honey), candied almonds, fritters, tarts, and dried fruit. The most common final course at elite medieval meals—referred to in France as issue—consisted of a sort of digestif of hippocras (spiced wine) and whole sweet spices, often candied. See comfit and hippocras. It was only in seventeenth-century France that the final course in a multicourse meal came reliably to be called “dessert.” But even then, it was not entirely devoted to sweet dishes any more than the preceding courses were consistently savory. In France, as in Italy and England, there were also meals made up almost entirely of sweets where the focus was on artistry mingled with ostentation, rather than on the food per se. In medieval and early renaissance England, a banquet of sweetmeats, sometimes termed simply “a banquet,” might take the form of an entire meal devoted to sweets. This repast was occasionally served after a meal, which itself consisted of both sweet and savory dishes. The sweet banquet was sometimes served at a separate table, in a separate room, in a garden setting, or even in a separate “banketting house,” where the tables would be set with displays well in advance. See banqueting houses.

Until the seventeenth century, sweet and savory were not always distinct. In Christoforo di Messisbugo’s sixteenth-century Italian banquet menus, meals typically began with an assortment of confectionery and concluded with more of the same. But just about every other dish in the intervening courses, whether a fish pie or stewed capon, had some sugar added to it, too.

The situation was not significantly different in France. Food historian Jean-Louis Flandrin has estimated that some 80 percent of still-extant French recipes for meat and fish dishes were sweetened in the fifteenth century. The number had dropped to around 50 percent a hundred years later, and in the seventeenth century, some 30 percent of these dishes were still being sweetened. Increasingly, though, the trend was to segregate sweet from savory. Just why this split occurred in France remains hazy, and the explanations are unsatisfactory. Flandrin implies that it signaled a return to earlier French habits, once Italian Renaissance fashions had waned (Italian food was notably sweeter than the French). Chauvinism may well have had something to do with the change; certainly, the first influential cookbook to be published following the period of Italian influence was self-consciously titled Le cuisinier françois (1651), the first cookbook ever to be characterized with a national identity. This nationalistic food consciousness and growing gap between sweet and savory also happen to parallel the demise of spiced food in France. Sugar was initially thought of as a spice; once it had been recategorized in people’s minds as a confectionery and baking ingredient, it perhaps had no place in the new, mostly spice-free cuisine. This is not to say the change occurred overnight; Le cuisinier françois offered plenty of recipes for sweetened meat and fish dishes. Nevertheless, though sweet and savory were still served side by side, they were increasingly not blended on the same plate.

Service à la française

Affluent French seventeenth- and eighteenth-century menus most commonly consisted of three courses (services) made up of platters both large and small, each multidish course served more or less simultaneously buffet-style. This type of presentation was referred to as service à la française (even though it was commonplace all over Europe). Generally more and more sweet dishes were served as the meal progressed. In the first course they were rare, while the second course contained a scattering of side dishes called entremets (literally, “between the dishes”), which could be both savory and sweet. See entremets. In a menu from 1690, listed in François Massialot’s Le cuisinier roïal et bourgeois (1691), members of the royal family and guests could choose among entremets of ham or pheasant pies but also blancmange, fritters (beignets), and apricot marmalade–filled tarts. See blancmange and fritters. These sweet items were interspersed among 22 platters of roast beef, mutton, suckling pig, and “all sorts of poultry.” Other menus suggest entremets of sweet omelets, fruit custards, crème brûlée, even a sugared artichoke custard. See crème brûlée. It was only once this service had been fully cleared that the dessert course was served. The 1690 Dictionnaire universel defined dessert as “the last course placed on the table … composed of fruits, pastry, confectionery, cheese, etc.” This final course was the responsibility of the office or pantry, whereas the earlier dishes came from the kitchen. Accordingly, what characterized the dessert course was not so much that it was sweet, but that it was cold. It was also the most visually exciting part of the meal. Though some degree of spectacle distinguished every course, the final dessert service deployed the color, texture, and sculptural potential of confectionery with sometimes fantastic results. See sugar sculpture. Broadly speaking, the confectioners followed the current style in the other applied arts. Thus, seventeenth-century dessert tables featured baroque pyramids of sparkling sweetmeats; eighteenth-century displays were replete with neoclassical statuary often set on a mirrored surface; the Romantic period saw pièces montées resembling crumbling classical ruins; and the Victorian period brought a ponderous historicism. With the arrival of service à la russe, these spectacular displays largely ceased to exist as table decoration was limited mainly to flowers and individual servings were brought to each diner in turn. In bourgeois homes, a fancy dessert might be displayed on the sideboard throughout dinner, but it was a shadow of its ancien régime ancestors.

According to Arthur Young (1792), an English writer visiting France on the eve of the Revolution, “dessert” was to be expected at even a modest meal. This practice apparently stood in marked contrast to the custom in England. “A regular dessert with us [the English] is expected,” he explains in Travels during the years 1787, 1788, and 1789, “at a considerable table only, or at a moderate one, when a formal entertainment is given; in France it is as essential to the smallest dinner as to the largest; if it consists only of a bunch of dried grapes, or an apple, it will be as regularly served as the soup.” Throughout his travels, Young described several of these desserts, which typically consisted of fruit, nuts, biscuits, and wine—more or less in line with the definition current in eighteenth-century England. Ephraim Chamber’s Cyclopaedia (1741) defines dessert as “the last service brought on the table of people of quality; when the meats are all taken off. The dessert consists of fruits, pastry-works, confections, etc.” Other English sources, however, limit dessert to a final course of fruit only.

The French system of serving meals in three or more courses concluding with one called dessert was emulated across Europe. Naturally, not everyone could afford the splendors of Versailles. Heinrich Klietsch’s and Johann Hermann Siebell’s Bamberger Kochbuch (1805), intended for both “noble and bourgeois tables,” includes 78 suggested menus, mostly consisting of two courses. The first is exclusively savory, whereas the second may include anything from roast duck to capon pies to ice cream, sweet jelly, and cake. In addition to these menus, the authors include a selection of “dessert plates.” Although not all are specified, those singled out include sorbet, ice cream, fruit, cookies, and “other confectionery.” Given that these dessert plates are always listed as the last item of the second course, it is likely that they arrived at the table after the other items had been eaten, although no indication exists that the table had been cleared in the interim, as it was in France.

Service à la russe

French cuisine, the trendsetting style across ancien régime Europe, underwent its own revolution with the fall of the Bastille. With the decapitation of the old aristocracy, the grand, buffet-style courses made up of multiple dishes were supplanted by a form of sequential service adopted from a Russian model—hence the name service à la russe. The change was very gradual and not universally appreciated. The great chef Carême, for one, had little use for it. See carême, marie-antoine. In this new style, all the diners ate the same food, more or less, and the dishes arrived one after the other, much as they do today. The entremets, increasingly mostly sweet, shifted to the penultimate position, with dessert following. In other words, now two sweet courses concluded a meal. Flandrin points to the shift in language between menus in the eighteenth century, where “dessert” was the term for a course, to the late-nineteenth-century use of “desserts” (in the plural) to refer to the sweet foods themselves. By that point, the entremets often consisted of a sweet, creamy dish such as ice cream or bavarois, whereas dessert might include cakes, cookies, fruit, or petits fours. See desserts, chilled; ice cream; and small cakes. In France, a cheese course was sometimes slipped between the two.

By the 1950s, the entremets and dessert courses had elided into one, resulting in today’s most common sequence of entrée, main course, salad, cheese, and dessert. The menus served at the Elysée Palace give some evidence that this shift toward the modern sequence occurred during World War II. Today, the distinction between entremets and dessert has mostly been lost. The most recent edition of the Académie française dictionary defines entremets as “a sweet preparation served after the cheese and which may take the place of dessert.” At least when it comes to dessert, the West largely followed the French example.

Dessert in the United States

Initially, Americans aped the British model. They could, for example, look to Maria Eliza Rundell’s widely reprinted A New System of Domestic Cookery (1807) for what was appropriate for a second course—mainly birds, game and shellfish, vegetables, fruit tarts, stewed apples, cheesecakes, and “all the finer sorts of Puddings, Mince Pies, &c.” The book was apparently not intended for “people of quality,” since it makes no mention of dessert. Robert Robert’s The House Servant’s Directory (1827) clearly aimed higher up the social scale. His dessert is served very much in the French manner: following two courses (served à la française) and a cheese course, the table is completely cleared before resetting for a sweet course of cake or possibly ice cream or blancmange. See blancmange and cake.

Hotels and restaurant menus in the latter half of the nineteenth century tended to break down sweet foods into two, not always easily understood, categories: pastry and dessert. The former included pies but also occasionally pudding; the second, fruit and nuts but also sometimes jellies, sponge cakes, ice cream, and charlotte russe. The distinction began to evaporate in the early twentieth century, even though fancy menus might well continue to include two sweet courses in the French style.

Today, a single dessert is the most common conclusion to a multicourse meal, though many fine dining restaurants make a habit of serving chocolates, petits fours, or some other sweet nothing after the official dessert has been cleared. See mignardise. As in France, dessert has also come to include any sweet food that might be served at the end of meal no matter when it is eaten, leading mothers to reprimand their children about not eating ice cream, cupcakes, pie, and other “desserts” before dinner.

See also charlotte; france; gelatin desserts; italy; pie; pudding; and sponge cake.

dessert design refers to the presentation of the course, generally consisting of sweet foods, that comes at the end of the meal.

Derived from the French verb desservir, dessert is what arrives after the table is “unserved” or cleared, and after our nutritional needs have been met; it is, in that sense, superfluous. See dessert. In his Grand dictionnaire de cuisine (1873), Alexandre Dumas wrote that there are three types of appetite: that which comes from hunger; hunger that comes with eating; and “that roused at the end of a meal when, after normal hunger has been satisfied by the main courses, and the guest is truly ready to rise without regret, a delicious dish holds him to the table with a final tempting of his sensuality.” Dessert requires this third type of appetite; its aesthetic display and sensuous experience are of primary importance.

Dessert is as much about form as it is about taste. Confectionery and baking, from dough to caramel to marzipan, lend themselves readily to sculpture, for example. See sugar sculpture. As a type of plastic art, dessert therefore is more likely to borrow from and contribute to the other art disciplines of its time, from architecture to fashion. Even the language of dessert making—molding, casting, dyeing, setting—and its associated tools have little in common with cooking. See confectionery equipment and pastry tools. Desserts are shaped, constructed, and fabricated (and, now, mass-produced) with an eye toward form; taste is often secondary. They have long been prepared by professionals with specialized tools and equipment in facilities dedicated to sweets, explicitly separate from the kitchen. See pastry chef. Ultimately, dessert’s place on and at the table is to amuse, not feed, and, historically, to communicate power or status, provide a locus for ritual and tradition, exchange cultural traits, even transcend the laws of gravity and physics. Desserts were made to awe, to show off, to delight. So what is dessert, after all? It is design: “the process of inventing things which display new physical order, organization, form, in response to function,” as theorist Christopher Alexander explains on the first page of his landmark 1964 book Notes on the Synthesis of Form.

Luxury at a Large Scale

Sugar is the primary building material of dessert. Even before the idea of this separate and final course fully evolved, a tenth-century Arab recipe described marzipan shaped like fish and perfumed with camphor. See marzipan and middle east. In early Renaissance Italy, Leonardo da Vinci wrote in Notes on Cuisine of the fate of his marzipan: “I have observed with pain that my Signor Ludovico and his court gobble up all the sculptures I give them, right to the last morsel, and now I am determined to find other means that do not taste as good, so that my works may survive.” The ultimate luxury commodity, his chosen medium of sugar was preservable, malleable, and believed to have medicinal properties. See medicinal uses of sugar. And (unfortunately for Leonardo’s sculpture), it was edible! Symbolically, technically, and gastronomically, sugar was the perfect material for public consumption—panem et circenses combined in one form.

From Lisbon to Antwerp, extravagant state, noble, or church banquets were followed by even more elaborate sugar collations. In a separate room, tables abounded with large sugar-paste sculptures depicting important people, fantastic buildings, and mythological creatures, often gilded or silvered to underscore their richness. See banqueting houses. Unlike the main meal, which was produced by the kitchen, the sugar work was created by individual artisans, sculptors, or apothecaries in their workshops. In 1574 sugar sculptures for a banquet given in honor of Henri III of France were the designs of Jacopo Sansovino, one of Venice’s chief architects, whose loggetta still adorns the base of Campanile di San Marco. That a sugar sculpture might be on par with a building shows the primacy of sweets not as food, but as an expression of power and carrier of meaning, much like a church, a palazzo, or a fortress. See symbolic meanings.

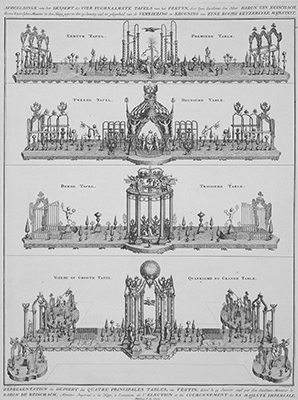

This 1747 plate depicts the desserts of preserves, sugared almonds, fruit, and ices displayed on the head tables of a banquet given by Judas Thaddäus, Freiherr von Reischach, for the coronation of Holy Roman Emperor Francis I. Composed as architectural tableaux set in formal gardens, the desserts are allegories on historical events from the death of Emperor Charles VI to the election of Francis I. getty research institute

Innovation and Inspiration

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries brought a number of innovations. The ascendance of the French court (and gardens) at Versailles brought with it a new style of dining in both preparation and presentation. Service à la française meant that the number of dishes for each course matched the number of diners and was served simultaneously, with dessert as a separate service. The kitchen was divided between the cuisine, where the meal was prepared, and the office, which was solely responsible for dessert, including ices. See ice cream. Each household department produced complex menus, describing the courses and particular dishes. The office was also stocked with the latest innovations in design: sophisticated containers, molds, and freezing pots. Service en pyramide stacked multiple layers of preserved fruit, sugar pastes, and plant material on successively smaller tiers of silver or porcelain. Eventually, these dessert sculptures grew so extensive that they became entire miniature gardens, which remained on the table throughout the entire meal. And, finally, cookbooks with engraved plates of elaborate, expressly axial table plans rivaled design treatises on architecture, landscape, and fortification. Tables became landscapes unto themselves, in which the desserts represented statuary, plants, or buildings. The period’s quest for verticality as a mark of (royal) triumph over a landscape was achieved far more easily with towers made of sugar on a dining table than with any building materials in a city or countryside.

Antonin Carême, known as the first celebrity chef (Talleyrand, Napoleon, and Tsar Alexander I were among his clients), and one of the last in a long line of culinary figures in French haute cuisine, was a celebrated creator of such tablescapes. See carême, marie-antoine. Working at a patisserie on rue Vivienne in Paris, he would walk across the street to the Bibliothèque Nationale, where he drew inspiration from the oversized illustrated catalogs depicting architectural wonders from Rome to Egypt. His resulting pièces montées (set pieces) included castles, pyramids, and temples inspired by ancient cultures and also borrowed from the neoclassical architecture that was being taught down the street at the École des Beaux Arts. For these confections made of spun sugar or pâté morte (dead pastry or decorative pastry without yeast), taste was irrelevant; the goal was appearance. In fact, although a few elements such as flowers or fruits may have been edible, the larger elements were often kept and stored for another occasion (bringing to mind the tradition of keeping slices of a wedding cake, or bride’s cake, to celebrate anniversary years later). See wedding cake.

In 1803 Carême opened his own very successful patisserie, in which he displayed his pièces montées in the windows, bringing in tourists and locals alike. Previously available only to the elite, desserts now reached a larger public thanks to a drop in sugar prices resulting from increased production in the colonies. Newly affordable, sugar was used to sweeten chocolate, coffee, and tea and, inevitably, to create sweets to accompany them. As dining hours shifted to later in the day, these snacks filled a void in the long stretches between meals, and by the nineteenth century, teatime (the French goûter) was firmly established. See sweet meals and tea. From London to Madrid to Vienna, the political, social, and cultural life of the bourgeoisie centered around coffee, chocolate, and tea houses, whose delicate confections were supplied by patisseries. Porcelain plates, influenced by the rococo trompe l’oeil sugar sculptures of previous centuries, now displayed all manner of tarts and éclairs, whose size was more appropriate to this new meal. As the scale of desserts shrank, the influence of fashion and the decorative arts on their designs grew; color, texture, and pattern came to the fore. Since sugar was no longer a luxury (and therefore status symbol) in and of itself, desserts had to display artisanal quality and the latest fashion. Coupled with the emergence of nouvelle cuisine and service à la russe (courses served sequentially, allowing for food to be brought to the table fresh and hot), this new style of dessert brought with it a new appreciation for taste.

A Desire for Speed

Toward the turn of the twentieth century, dessert again began to change, and nowhere was this clearer than in the United States. The burgeoning (and busy) American middle class had few of the artisan bakeries available in continental Europe, and so the focus was on home cooking. Instead of relying on domestic help, Americans looked to science and technology. Into the void came kitchen machines like eggbeaters and chemical leaveners such as baking powder, all of which sped up the baking process. See chemical leaveners and whisks and beaters. Product manufacturers distributed cookbooks full of quickbread recipes, encouraging the widespread adoption of such tools. Industrialization and mass production created a dessert culture that was more about speed than refinement, taste than presentation.

Today, after a century of mass-produced and machined biscuits and chocolates, dessert has lost its place at the table. Perhaps the clearest example is the recent food fad, the macaron. See macarons. The brand best known for macarons is the Parisian patisserie, Ladurée, which ran a fashionable nineteenth-century tea salon designed by the painter Jules Cheret, who took inspiration from the Paris Opera House. Ladurée’s macarons are still made in France with the color palette of the original Cheret design, but they are flown in the tens of thousands each day to outlets worldwide and can be found in any major airport, usually just before the security gates. Even McDonald’s recently introduced macarons in its McCafés. Once part of a tradition of confections to be savored in a social setting, today’s macarons are a mass-produced item to be eaten alone, quickly—and usually on the go.

The Past in the Future

Interestingly, the most recent developments in dessert design harken back to the elaborate confections of Venice and Vienna when taste was secondary but the show was everything. Bompas & Parr, the British food designers (trained as architects) who repopularized jelly by treating it much like sugar sculptures of their day, use sweet as spectacle. For New Year’s Eve in 2013 in London, in collaboration with food technology experts and pyrotechnicians, they created a multisensory firework display, in which revelers smelled and tasted fruity mists and edible banana confetti matched to the fireworks (all, of course, both halal and kosher). They must have been influenced by the description of a 1549 feast to welcome Philip II to the Netherlands, in which guests were led to an “enchanted hall” at midnight, where sugar collation descended from the ceiling, along with hail and perfumed rain made from sugar candy.

In the United States, the newest 3D printers can print chocolate, sugar, or candy, bringing the art of the confectioner and chocolatier to the home kitchen. The resulting elaborate creations can be made in a fraction of the time and with as little skill. One company, 3D Systems, is collaborating with Hershey’s to offer 3D-printed food to consumers. See sugar, unusual uses of. Whether a democratic experience like fireworks along the Thames, do-it-yourself (DIY) or mass customization, dessert is designed for and by everyone. But what of taste? Here, the dessert maker’s dilemma parallels that of other design professionals in finding a balance of form and function.

See also café; cake and confectionery stands; competitions; confection; epergnes; gelatin desserts; leaf, gold and silver; paris; plated desserts; serving pieces; trompe l’oeil; and venice.

desserts, chilled occupy the crucial middle ground between the frozen and the cool: chilling is an essential element in their creation and enjoyment. Most cold desserts are chilled in advance of serving, and gateaux or dessert cakes layered with whipped or enriched cream are often said to improve after a few hours—or even a rest overnight—in the fridge. Alchemical transformations achieved through setting and stabilizing in a truly cold rather than a merely cool place earn these chilled desserts a special category all their own.

Cold Chilled Desserts

These desserts are thoroughly chilled both to finish them—usually to ensure a set—and for service.

Bavarois

Also known as a Bavarian Cream or crème Bavaroise, this delicate egg-yolk custard, aerated with whipped cream and set with gelatin, is both a dessert in its own right and a key component of others. It can fill a cold charlotte or be molded with paper to stand proudly above the rim of the dish for a chilled “soufflé.” See charlotte; custard; gelatin; and soufflé. Often scented with alcohol and flavored or decorated with fruits, nuts, or chocolate, the bavarois is chilled for four hours to preserve its fluffy lightness while ensuring a firm presentation. The great French chef Carême included bavarois recipes in his early-nineteenth-century cookbooks, though contemporary French sources tend to credit it as a Swiss invention, and the late-nineteenth-century chef Escoffier suggested that it should more properly be called a Muscovite. See carême, marie-antoine and desserts, frozen.

Cassata

Sicilian cassata is composed of a set fruit cream (similar to crème pâtissière) sandwiched between savoy biscuit or sponge layers soaked in alcohol and enclosed in marzipan. It is chilled for approximately three hours before serving. See cassata.

Jelly

Often thought of as a children’s dessert (in the form of Jell-O or packet jelly), a clear jewel-like jelly of fruit juice set with gelatin, agar agar, carrageen, guar or xanthan gums, or arrowroot, and sometimes flavored with wine or alcohol, can be a sophisticated dessert. Molded into beautiful shapes, it might be layered in different colors and flavors, made with milk for a creamy clouded effect, or have fruit suspended in it. See blancmange and molds, jelly and ice cream. It must be chilled in order to set fully and should be served very cold.

Refrigerator or Chocolate Biscuit Cake

Composed of a variable combination of broken-up cookies, butter, sugar, nuts, dried fruit, eggs, and chocolate, these cakes are not baked. Hard ingredients (butter and chocolate) are melted to facilitate mixing, and the result is formed into a log or loaf shape, hardened in the refrigerator, and served very cold in slices.

Partially Frozen Desserts

Some chilled desserts are more deeply chilled than others, or even partially frozen. Others are composed of a combination of frozen ingredients like ice cream or sherbet and nonfrozen ingredients like fruit, sauces, nuts, and other edible decorative elements, such as sprinkles or jimmies. See ice cream; sauce; sherbet; and sprinkles.

Parfait

A perfect balance of soft and firm, a harmony of whipped cream, egg yolks, sugar, and flavor (often alcohol), the classic French parfait has a smooth texture whose secret lies in technique. Instead of the usual custard found in ice cream, sugar syrup at 248°F (120°C) is beaten into egg yolks before mixing with the other ingredients and freezing for 3 to 4 hours. In the United States, the term “parfait” refers to a layered ice cream or frozen yogurt confection similar to a sundae.

Semifreddo

These “semi-frozen” ices, also known in Italy as perfetti, are soft and light in texture, somewhere between a mousse and an ice cream, one part custard and one part whipped cream. Although many recipes confuse semifreddo with parfait—and they are closely related as the alternate Italian name attests—they are technically different. For semifreddo, sugar syrup at 248°F (120°C) is added not to egg yolks, as for parfait, but to beaten egg white, as for Italian meringue. See meringue. The result is an even lighter, softer texture. Many simpler recipes exist for domestic cooks that borrow the name, using less skilled techniques to achieve a similar texture. Some versions do not contain eggs at all, effectively being a semi-frozen uncooked cream. Others incorporate granular sugar into stiffly beaten egg white, as for French meringue. The majority comprise a light mixture of whole eggs and sugar whisked, zabaglione-like, over a double boiler and cooled before folding in whipped cream and perhaps incorporating other ingredients like fruit, honey, or chocolate. See zabaglione. Regardless of cooking technique, semifreddos are never churned in an ice cream machine and are usually frozen into molds, often in a loaf shape that is then sliced for serving. They do not freeze hard; sometimes they are only chilled in the fridge, not frozen. The end result must be cold enough to hold its form and be sliced, but still a bit soft.

Sundae

A sundae is an individual layered dessert of ice cream in one or more flavors, often served in a tall glass. See sundae. It usually comprises a base layer of syrup or crushed fruit, followed by two scoops of ice cream finished with more fruit or syrup, a dry topping like crushed or chopped nuts, and a lavish flourish of whipped cream; it is always crowned with a maraschino cherry with its stem intact. Hot fudge sundaes have heated—usually fudge—sauce. Sundaes may be made more elaborate with layers of fruit instead of syrup, and with different combinations of sauces and decorations. They are often given evocative names, like the Dusty Road, a chocolate sundae sprinkled with malted milk powder; or the All-American Victory sundae in patriotic shades of red, white, and blue that was popular after World War II, composed of vanilla ice cream with a marshmallow topping and both maraschino cherries and fresh blueberries. The Knickerbocker Glory, an idea imported to the United Kingdom from the United States, is presented in a taller glass with chocolate syrup at the base, followed by three scoops of ice cream with alternate layers of various crushed fruits between them. The whole is topped with whipped cream and a maraschino or glacé cherry. An American parfait is similar, though it has no chocolate syrup and its three scoops of ice cream may be separated by either crushed fruit or fruit syrup. It also includes a layer of chopped nuts below the whipped cream. Health-conscious modern versions of the parfait are made with layers of yogurt and granola.

Peach Melba, constructed of vanilla ice cream topped with poached peaches and raspberry coulis, was created by the chef Auguste Escoffier for Dame Nellie Melba, to celebrate her 1892 Covent Garden performance in Wagner’s Lohengrin. On its first outing, it was apparently presented on the back of an iced swan and topped with spun sugar. See escoffier, georges auguste.

Poire Belle Hélène, invented by Escoffier in 1864 and named for the Offenbach opera, is a sophisticated relative of the sundae, composed of a poached pear, vanilla ice cream, and chocolate sauce decorated with crystallized violets.

Split

A split is a horizontally arranged variation on a sundae, classically including a banana, though variations including tropical fruits such as mango or pineapple are increasingly popular.

The classic banana split includes three scoops of ice cream in the center of a dish, bounded on both long sides with a banana sliced lengthways. Each scoop is topped with chocolate or fruit sauces, and the whole is decorated with whipped cream, chopped nuts, and cherries. Variations such as a banana-boat split may include sponge cake at the bottom of the dish.

See also blancmange; charlotte; cheesecake; chocolate pots and cups; cream; custard; desserts, frozen; fools; mousse; tart; and trifle.

desserts, flambéed, make dramatic use of flame to create spectacle for the diner. Whether deftly performed at a restaurant table with a spirit burner and polished copper pan, or rushed blazing from the family kitchen to a darkened dining room, a flambé can create a thrilling grand finale to a meal. Why stop at a few candles when you can set the whole dessert alight?

Technique

Flambéing is the technique of using alcohol to flame food. In dessert dishes it is usually employed as a final presentational step for a hot or warm dessert and therefore generally done in front of diners either at their own table or a side table. The dish is often briefly finished in butter and sugar (or sugar alone) to achieve some caramelization before the alcohol is added. For maximum effect, attractive cooking utensils—traditionally copper saucepans and chafing dishes—are used over a spirit burner or candle flame, depending on how much of the cooking has already been done in the kitchen. The method of flambéing varies according to how much sauce or juice is in the dish to be flamed. If little or no liquid is already present, the chosen spirit can simply be poured onto the dish and the pan either tilted to catch the flame or a match applied. If the dish is very juicy or has a sauce, then more spirit is usually required to obtain a good flame. It is heated separately in a ladle or small pan, set alight, and poured already flaming onto the dish. Once the flames have subsided, the dessert is served.

Alcohol

To obtain maximum flare, alcohol with a percentage volume of 40 or over is usually recommended for flambéing, selected according to the ingredients in the dish. Fruit liqueurs and strong alcohols like cognac, gin, vodka, bourbon, or whiskey are generally specified, using classic pairings like rum for bananas, kirsch for pineapple or cherries, curaçao for orange, brandy for coffee desserts, and so on. See liqueur. There is disagreement on how much of the alcohol is actually reduced or “burned off” during the flaming process, and how much flavor the flambé imparts, but it seems safe to assume that part of the thrill of a flambéed dessert lies in its scent of almost-burned caramel and retained alcoholic content.

Dishes

Almost anything can be flambéed, and numerous recipes exist for grilled, baked, poached, and fried fruit desserts, from kebabs to cake and ice cream toppings, as well as layered, folded, or rolled pancakes with various stuffings and sauces sent aflame to the table. Savarins, vacherins, babas, meringues, bombes, and sweet omelets are all excellent subjects for the flambé treatment, generally given the epithet “Surprise” to indicate their fiery incarnation. A lick of flame gives a spectacular finishing touch to a Baked Alaska. See baked alaska. The truly classic dishes are those in which the flambé is a component part of the dish, the ones unimaginable—even unworthy of their name—without the flambé step.

Bananas Foster is a 1950s creation from New Orleans, a variation on a banana split made with baked bananas over vanilla ice cream with a dark brown sugar, cinnamon, and butter sauce, flambéed with rum.

Cherries Jubilee was created by Auguste Escoffier for Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee celebrations in 1897. Cherries are lightly poached in lemon syrup and served flambéed with cherry brandy or kirsch over vanilla ice cream.

Crêpes Suzette is the ultimate in table-side flambé, of disputed late-nineteenth-century origin and now somehow redolent of 1970s restaurants, mustachioed waiters, and polished copper pans. Thin pancakes are spread with sweet orange butter enriched with curaçao, briefly fried in foaming orange butter and deftly folded in three to make a round-ended triangle. Brandy, Cointreau, or Grand Marnier is added to the caramelized butter in the pan, ignited, and poured over the neatly stacked pancakes.

See also desserts, chilled; escoffier, georges auguste; new orleans; and sundae.

desserts, frozen, are compositions with ice cream or frozen yogurt at their core, combined in various ways with other dessert ingredients such as sponge cake, biscuits, nuts, fruits, creams, and sauces. Distinct from desserts individually constructed on the spot from a combination of fresh and frozen ingredients, frozen desserts are built in advance from the components, frozen into a composed whole and presented in their entirety for serving. These creations may be as simple as an ice cream cake or pie, or as extraordinary as a molded and layered bombe in the shape of a ball, a fruit, or an architectural model.

With the right tools, any frozen matter can be sculpted and formed, and both ice and ices have long been carved and molded into specific shapes for elite tables. Elaborate molds were in use for high-status occasions as early as 1714, when a carved ice tree trunk set in chocolate foam soil and hung with 150 tiny fruit-shaped bombes was presented at a celebration given by the Austrian ambassador to Rome. By the early nineteenth century, fancy ices were commonly served in wealthy households, and as refrigeration technology developed in the later nineteenth century, ice cream in all its variations became accessible to a much wider range of people even as manufacturing innovations allowed for the mass production of inexpensive metal goods—molds among them. See ice cream and molds, jelly and ice cream. The Victorian era saw an explosion in molded ice cream constructions, all the way up to the epic scale of Eppelsheimer’s 39-inch-high, 17-liter ice cream Statue of Liberty of 1876. From the mid-twentieth century onward, frozen desserts that go beyond a straightforward tub of ice cream have also become an increasingly important category in industrial food production.

Molded Desserts

Desserts frozen in molds are perhaps the most spectacular of all frozen desserts. The molds themselves are often extraordinary and elaborate, and the internal engineering needed to ensure a stable result requires the layering of different styles of ice creams, sorbets, and other ingredients, which can lead to an interior as visually exciting as the exterior. Since a molded dessert needs to be soft enough to eat and cut while being firm enough to survive presentation and service, it is important to use a slow-melting ice on the outside, such as sorbet, and a softer one, like a parfait or spoom (a lighter, frothier sorbet), on the inside.

Bombe

Bomba in Italian, this is a molded ice cream dessert in a hemispheric shape, usually with one flat surface for stability on the plate when serving. Baked Alaska is a bombe that manages to be baked, frozen, and flambéed all at the same time. See baked alaska and desserts, flambéed.

Crème à la Moscovite was a Victorian ice served partially, rather than fully, frozen. Related to the chilled dessert bavarois, the Moscovite was set with isinglass or gelatin, giving it a slightly jellied texture, and molded into a bombe or cylinder shape.

Nesselrode Pudding, a spectacular frozen dessert, is said to have been invented in 1814 by the great chef Carême for the Russian diplomat Count Karl von Nesselrode. See carême, marie-antoine. It is a rich cream custard enriched with sweet chestnut purée, currants, raisins, candied fruit, whipped cream, and maraschino liqueur. Molded in a bombe or a cylinder, it is served with a cold maraschino custard sauce.

Spumoni, an Italian ice molded in a hemisphere, is composed of two complementary layers, usually a custard-based ice cream on the outside and a semifreddo or parfait inside.

Tortoni or biscuit tortoni, a classic of New York City (although almost certainly descended from Menon’s 1760 recipe for biscuits de glace), is a rich maraschino-flavored ice cream with biscuit crumbs mixed in and on top; the dessert is traditionally served in an individual paper case. It is unclear exactly how tortoni arrived in New York, but a recipe appeared as early as 1889 in The Table, a cookbook written by Alessandro Filippini, chef at the famous restaurant Delmonico’s.

Frozen Versions of Other Desserts

Many commercial suppliers offer frozen variations of typical cakes and desserts, which can also be prepared at home.

Ice Cream Cake, Gateau, or Cheesecake

An ice cream cake or cheesecake is a layered construction starting with a base of sponge cake, brownie, or a crunchy crumb, sometimes topped with fudge sauce before adding the chosen ice cream or ice creams in layers, with or without more layers of cake, and with suitable decorations.

Arctic roll, a British commercial classic, is a log of vanilla ice cream surrounded with raspberry jam and light sponge cake—like a Swiss roll without the interior spiral effect.

Ice Cream Pie

Ice cream pies are made up of a deep, baked pie crust filled with freshly churned or softened commercial ice cream, and usually topped with whipped cream or custard and garnished with nuts, fruit, or other toppings. Eskimo Pie is, confusingly, not a pie, but the American name for a confection the British call a Choc Ice: a small block of ice cream, usually vanilla, encased in chocolate. See eskimo pie.

Ice Cream Sandwich

The “bread” of the sandwich is usually made of triangular, circular, or rectangular wafers, which enclose a filling of ice cream. A fancier version, akin to a vacherin, may be made by using meringue instead of wafers. See meringue and vacherin.

Layered Ice Creams

Simpler ice cream desserts are formed with layers of different ice creams, usually in a rectangular loaf-cake shape that is easily sliced. The Neopolitan is composed of two or more different flavored and colored ice creams, often vanilla, strawberry, and chocolate. Pückler is a German variation on the Neopolitan, including layers of crushed macarons soaked in liqueur along with the ice cream layers. Viennetta, a globally available Unilever product, is made of extruded rippled layers of ice cream alternated with sprayed layers of compound chocolate. It is available in various flavor combinations.

See also chestnuts; custard; desserts, chilled; and italian ice.

See glucose.

See sugar and health.

Diwali is India’s most widely celebrated festival, an occasion that serves to remind humanity of the triumph of good over evil. On the night of the autumn new moon (between October and November), cities, towns, and villages in India sparkle with the glow of oil lamps, candles, and tiny string lights that decorate houses, walls, gardens, and public spaces. This array of lights is called deepavali in Sanskrit, and the modern Hindi term “Diwali” is derived from that. The festival is a most distinctive cultural and religious marker.

From the perspective of the agricultural calendar, Diwali is a postharvest celebration. It takes place after the main autumn crop has been harvested and there is cause to be thankful (except in years of disastrous droughts or floods) that the coming year’s food supply is ensured. Preparing the land for the winter sowing is preceded by the enjoyment of autumn’s bounty. Spiritually, however, Diwali is unique in being not only an affirmation of good over evil, but also an occasion celebrated by three religious communities: Hindus, Sikhs, and Jains. For Sikhs, Diwali is the anniversary of Guru Hargobind’s liberation from imprisonment in 1619, whereas the Jains believe it to be the day when the great reformer Mahavira achieved nirvana.

For Hindus, Diwali is draped in a rich tapestry of myths that vary from region to region. See hinduism. In the north, it is a celebration of Rama’s victory over Ravana. In the south, it honors Krishna’s killing of the demon Narakasura. In the west, it marks the day when Vishnu banished the demon king Bali to the nether regions. In all these areas, Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity, is worshipped during Diwali. For many business people, Diwali also marks the beginning of a new working year—a reflection of the occasion’s agricultural roots. In the eastern states (Bengal, Orissa, and Assam), however, it is the goddess Kali who is worshipped on Diwali instead of Lakshmi, and the story of her conquest of evil takes precedence over other Indian myths.

Out of this diversity of faith and myth, one factor unites all who celebrate Diwali—the eating and exchanging of sweets. The sense of a new beginning, whether in the field, at home, or in a place of business, is accompanied by the hope of better things to come, and the natural culinary expression of that mood may be seen in the extraordinary variety of sweets prepared in different regions of the country.

In northern and western India, women labor for days in advance to produce items made with flour, semolina, rice flour, besan (chickpea flour), sugar, clarified butter, nuts, and milk evaporated to a fudge-like consistency. The resultant profusion of laddus, barfis, halvah, kachoris, puris, and other goodies are consumed by families at home and widely shared with friends, neighbors, and colleagues. See barfi; halvah; and laddu. The custom of visiting people and bringing brightly wrapped boxes of sweets is witnessed in every city and town. The professional confectioners are equally busy, churning out their specialties and creating displays that are appealing to both eye and tongue.

One of the most indulgent festive comestibles is puran poli, a flatbread stuffed with a sweetened mixture of chickpea flour and pigeon-pea flour, fragrant with cardamom, rosewater, and kewra (screwpine) flower water. See flower waters and pandanus. The bread is fried in clarified butter and often dipped in warm, melted butter before eating. The mawa kachori is another seasonal stuffed treat, the filling made of solidified evaporated milk and chopped nuts. Another Diwali favorite is the balushahi, a richer, melting-in-the-mouth incarnation of a doughnut, emitting the aroma of clarified butter and gilded with festive silver foil. Among the laddus—round balls made with sweetened besan and aromatic spices—motichoor laddu is a particularly delectable version often served at Diwali. Tiny balls of besan dough are fried in clarified butter, dipped in syrup, and once cooled, formed into larger balls (sometimes with the addition of blanched almonds or pistachios) that are often decorated with edible silver foil.

In southern India, the same ingredients are used with a different culinary sensibility to create sweets for festive occasions like Diwali. Laddus, made with roasted besan, sugar, and prolific amounts of clarified butter, go by the name of maladu, maavu laddu, or pottukadalai. Susiyam, similar to puran poli, is made in the rounded shape of a laddu instead of a flatbread. The filling, consisting of cooked chickpeas (or Bengal gram), coconut, brown sugar, and toasted nuts, is stuffed inside a flour shell, shaped into a ball, and fried in coconut oil or clarified butter.

Milk plays the star role in items like rice pudding and a yogurt cheese called shrikhand. In eastern India, the traditional Bengali items such as sandesh, made with chana (or channa) or fresh curd cheese, also appear on the menu for Diwali. See sandesh. Although Bengalis celebrate Kali Puja during Diwali, that presents no obstacle to their indulging in the lipid-rich laddus, barfis, and halvah that are so common in the northern and western parts of India.

See also fried dough; india; kolkata; and mithai.

Dobos torte, pronounced doboshe, is Hungary’s most iconic layer cake, a round cake consisting of six thin, buttery, sponge cake layers, five layers of chocolate buttercream, and a layer of hardened caramel covering the top. See caramels and sponge cake. The top caramel layer is cut into individual slices (with a special Dobos torte knife) before it hardens, and those pieces are arranged on top of the cake. Dobos torte is served in nearly every cukrászda (patisserie) in the country.

Although Dobos torte is often mistranslated as “drum cake” (the Hungarian dob means “drum”), it is in fact named after its inventor, József Dobos (1847–1924), a baker, chef, prolific cookbook author, caterer, and culinary entrepreneur who came from a family of cooks going back generations. In 1878 Dobos opened a specialty gourmet shop in central Pest that sold an array of high-quality local foods and imported delicacies such as cheese, wine, caviar, and spices. The shop was known for its elaborate window displays and house-made products. Dobos’s most important creation was his namesake cake.

The Dobos torte debuted in 1885 at the National General Exhibition in Budapest, where Dobos presided over an elegant pavilion staffed by more than 100 people. Queen Elisabeth and Emperor Franz Joseph were among the crowd who visited his pavilion. “Those present cheered the royal couple, who were served personally by Dobos himself, writes Tibor Éliás in his book Dobos and 19th Century Confectionery in Hungary (2010). “They of course also tasted the latest novelty, after which another royal cheer erupted—this time in honor of the creator of the cake” (p. 87). Afterwards, Dobos was made a purveyor to the Imperial and Royal Court.

The Dobos torte “was born as a result of continuous experimentation on the part of the ever creative Dobos,” writes Éliás. The cake became a sensation not only in Budapest, but also throughout much of Europe, for several reasons. Unlike the other, more intricately decorated European cakes of the time, the Dobos torte, with its flat, shiny, unadorned caramel top, looked downright minimalist. The chocolate buttercream spread between the cake layers was also a new concept, and it became Dobos’s signature (and secret) ingredient. Both the buttercream and hard caramel were innovations that gave the cake a significantly longer shelf life, with no need for refrigeration. Dobos brought his cakes with him during his frequent travels in Europe, and shipping the cakes throughout the continent became an important part of his business. He designed special wooden boxes to keep the cakes cool and perfectly intact during their journey. The Dobos torte was regularly served at social events throughout the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

During Dobos’s time, his cake was much imitated by other patissiers in Budapest, but never successfully. Bakers did not figure out that cocoa butter was the secret ingredient in Dobos’s smooth chocolate buttercream. Tired of all the bad imitations of his cake, Dobos donated his recipe to the Pastry and Honey-bread Makers’ Guild in 1906 so that all pastry chefs would have access to the true recipe. Soon afterward, Dobos closed his shop. Despite his success, Dobos’s life did not have a happy ending. He lost most of his fortune, which he had invested in war bonds, during World War I.

The Dobos torte is as popular as ever in Hungary today—and also in Austria and other countries that were part of the empire—but it is rarely prepared at home because it is so labor intensive. The Dobos torte (often written phonetically as Dobosh torte outside of Hungary) has also inspired cakes as far away as the United States. In New Orleans the Doberge cake is a layer cake usually filled with chocolate and lemon pudding and covered in buttercream or fondant. See fondant. In Hawaii the popular Dobash cake is a chocolate chiffon cake with a chocolate pudding or Chantilly cream filling. Though many Hungarian pastry shops prepare the Dobos in its classic form, modern bakeries also experiment and create versions that would have been unrecognizable to József Dobos. In Hungary, however, no matter how experimental a pastry chef gets with his or her Dobos torte, chocolate and caramel are always present. Even today, it feels like a little luxury to sit down with a slice of elegant Dobos torte.

See also austria-hungary; cake; layer cake; new orleans; and torte.

Dolly Varden cake, a layer cake in the shape of a doll, inspires recollections of childhood whimsy. It has a long history within popular culture. Dolly Varden first appeared as a character in Charles Dickens’s Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of Eighty (1842). Described as a pretty, charming coquette, Dolly inspired fanciful portraits of her dressed in a cherry mantle and straw hat with red ribbons. All types of dedications to her followed, including flowered fabrics, parasols, paper dolls, dances, an amusing song, and even an iridescent trout. In the 1870s a fashion craze swept through London and New York, with Harper’s Bazaar featuring “Dolly Varden Costumes”—flowered dresses with wide, bustled skirts.