East Asia embraces long and broad historical continuities and connections in the confectionery cultures of China, Japan, and Korea that remain strong today. Sweets made from glutinous rice, for instance, are found in all these countries, as well as in Southeast Asia, notably Thailand and the Philippines. One can also trace the adoption of early versions of Western confectionery throughout Asia, as the example of Portuguese egg threads (fios de ovos) illustrates. See portugal’s influence in asia. This sweet, made by drizzling egg yolks into sugar syrup to form noodle-like strands, was originally a preserved food for Portuguese ships’ captains and their officers embarking on voyages of discovery and trade. It was introduced to Japan in the sixteenth century, where it came to be known as egg noodles (keiran sōmen). See nanbangashi. Versions of this Portuguese recipe may be found in China, Thailand, and Cambodia.

Over the centuries Chinese confections spread to Japan and Korea, but China’s historical influence on surrounding countries should be noted, especially in the dissemination of the ingredients for sweets, notably sugar, and the transference of the expertise to refine it. Sugarcane cultivation in south China dates to the third century b.c.e., and by the end of the 1800s sugar was China’s third most important export item. Besides Chinese merchants, the Portuguese and Dutch (from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, respectively) also traded in Chinese sugar to Asian countries and Europe. Sugarcane arrived in Okinawa by 1600 from China, and the technology to refine sugar soon followed. The Dutch introduced sugar to Taiwan in 1624, and cultivation continued on the island after the Dutch were driven out in 1662 and Taiwan was incorporated into China’s Qing empire in 1683. Japan sourced sugar from China beginning in the late 1500s, and Taiwan became the major supplier of Japan’s sugar after its colonization of the island in 1895. China, India, and Thailand remain in the top five sugar-producing countries globally. Guangxi province is the largest sugar-producing region in China, followed by Yunnan. Xinjiang, Heilongjiang, and Inner Mongolia produce 90 percent of China’s beet sugar.

Given that China is also one of the top five importers of sugar globally, it is not surprising that sugary confectionery is the largest sector of China’s commercial confectionery market, in contrast to Japan and South Korea, where in 2012 chocolate amounted to about 41 percent and almost 60 percent of the total market, compared to just 6 percent in China. The Japanese favor chocolate bars and premium chocolates, but in South Korea most of the chocolate is destined for use in cakes and cookies. Overall, chocolate accounts for almost half of the Asia Pacific confectionery market, which includes Australia, China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Mars Incorporated controls almost a quarter of the Chinese confectionery market, and the company also does significant business in South Korea, where it ranked among the top four sellers in 2012. See mars. Offering Mars some domestic competition is China’s Want Want Holdings, makers of popsicles, jellies, rice crackers, yogurt drinks, and other sweets. Ranked third in China is Lotte, a company founded in Tokyo but with its headquarters in Seoul. Lotte controls about 10 percent of China’s market and also dominates among its competitors in Korea, notably the sweet makers Crown, Orion, and Haitai. Lotte, which produces biscuits, chocolates, chewing gum, candies, ice creams, and nutritional health supplements, is one of the top 10 confectionery companies globally in terms of market share. Japanese sweet makers Meiji and Morinaga are among the top 20 in the same rankings.

China has had a profound historical influence on the development of confectionery in East Asia, but in terms of the modern market for mass-produced sweets in the Asia Pacific, in 2012 Japan accounted for 37 percent of the region’s confectionery market value, followed by China at 20 percent, India at about 5 percent, South Korea at 4.2 percent, and Taiwan at 3.2 percent. As China develops further economically, its market share will surely increase.

All the countries in East Asia have different local preferences in sweets; cereal bars, for instance, are becoming more popular in Japan but have yet to make significant inroads in South Korea and China. All three of these nations share a growing concern for healthy eating that might diminish sweet sales in the future, but that also offers niche markets for reduced-sugar confections in China and sugarless gum in Japan. Demand remains strong, nevertheless, especially for chocolate in Korea and Japan for holidays such as Christmas, Valentine’s Day, and White Day, celebrated on 14 March when men are supposed to purchase sweets for female acquaintances. See valentine’s day. Chocolate sales are also expected to rise in China as wealthier consumers seek premium sweets and become further acquainted with Western confectionery traditions.

See also china; japan; korea; sugar trade; and thailand.

Easter is a spring festival, a time for celebration in the Christian calendar after a late winter fast, and one that contains echoes of older, pagan rituals. The holiday is celebrated with sweetmeats in exuberant variety, prepared throughout the Christian world at a season when the earth is still barren: nut cookies, buttery fruit breads, fruitcakes, marzipans, molded heaps of new butter and sweetened curds, chocolate eggs, and sugar-dusted butter lambs. Common to all these special foods is sweetness, and all are baked in a quantity meant for sharing. The sharing of foodstuffs, particularly when pleasurable, is a powerful weapon in the armory of all religions, a reality not lost on the pragmatic fathers of the early church, who adapted their celebration of resurrection to the old festival of procreation. Those who take their lead from the founding fathers of Rome—including Italians, Greeks, French, Spaniards, Portuguese, and Russians—named the festival for Pesach, the Jewish feast of thanksgiving at which sweetened unmilled grains are eaten. Those who took their lead from the Norsemen chose Eostre, Norse goddess of spring and rebirth, whose name has given the word “Easter” to English.

Alone among the feast days of the church, Easter’s date is movable. Calculated according to the pre-Christian lunar calendar, it is further proof of a debt to the ancient rites of spring. Not all rituals associated with the old ways were welcomed by the new. Nuts and seeds could be considered acceptable symbols of resurrection, but not so the rowdy egg rituals—egg pacing, rolling, and cracking—associated with Eostre, which may or may not have been an invention of the Venerable Bede, anxious to distance his faith from pre-Christian rituals. Nevertheless, a memory of these activities survives in the chocolate eggs hidden for children by the Easter bunny, whose predecessor, the hare, Eostre’s favorite (and still a creature associated with magic among the Celts), was charged with identical duties, though the beneficiaries were more likely to be young lovers in search of solitude.

Regional differences in climate and history influence the Easter menu, but the need for sweetness, the taste of ripeness and promise of harvest, is acknowledged by all. Eostre’s sacred month is April, the planting month, the time when flocks and herds return to productivity, replenishing store cupboards, delivering fresh cream and newly laid eggs to restore health and hope at the darkest time in the farming year. All such foods were (and are, particularly in Eastern Europe but also in the more remote regions and islands of the Catholic Mediterranean) taken in a basket to the churchyard to be blessed; the same symbolic foodstuffs are eaten at funerals and by the graveside on Days of the Dead. See day of the dead and funerals. Most curious of these preparations is the egg-cheese, a large round ball of hard-cooked custard drained overnight in cloth, prepared for the Easter basket by Ruthenes, a population of Ukrainians marooned in Slovakia who follow the ways of their forefathers. Cookbook author Catherine Cheremeteff Jones (2003) also recalls a meal of singular sweetness and richness shared with her Russian Orthodox family at Easter, when butter and cream were newly available in spring: “The centerpiece of the feast is paskha, molded and decorated sweetened curd-cheese enriched with additions of crystallized fruits, dried berries and nuts and traditionally eaten with kulich, a sweet, butter and egg-enriched bread baked in a tall round mold and traditionally taken to church to be blessed.”

Sweet things, many of Arab origin, were traded from south to north. Exquisite miniature marzipan fruits exported from Sicily illuminate the Easter table in Holland. In Britain, historian Anne Wilson (1973) traces the origins of the Easter Simnel to festive biscuits made with fine flour, simla, milled by the Romans. The preparation vanished for a time to reappear—a form of resurrection—as rich fruitcake to be taken home at Easter. Baked on Mothering Sunday (Mid-Lent Sunday, a day on which the Lenten fast was relaxed) by young servant girls employed in Victorian households, this Easter message was layered and topped with marzipan. It is now somewhat confused by a decoration of fluffy toy chicks and sugar eggs with (or without) a rim of 13 little marzipan balls, one for each of those present at the Last Supper. See fruitcake.

Evidence of similar confusion—a measure, perhaps, of reluctance to abandon the merry rites of spring for the somber rituals of the Christian Easter—was identified by artist Daniel Spoerri (1982) in the 1970s among the islanders of Greece. Whereas the Lenten fast was reported as strictly observed until midnight on Easter morning, thereafter the air was heady with the scent of Easter baking as every household set about the joyous task of exchanging sugared trays of sweet things—almond cakes flavored with rosewater, cinnamon-dusted butter biscuits, doughnuts drenched in honey—to be shared with all, whether neighbor or friend or passing stranger, a tradition surely as ancient as the rocks upon which the congregation built their church.

In bread-baking regions, traditional Easter cakes—yeasted doughs, sweetened and enriched—are sometimes baked in anthropomorphic shapes with unshelled eggs dropped in the belly or under the tail. See anthropomorphic and zoomorphic sweets and breads, sweet. In Germany, these breads can take the form of a fox or a hare, Eostre’s favorite. In Italy, says cookery writer Ursula Ferrigno (1997), the most popular shape for sweet Easter breads is the dove, the symbol of peace, while in Spain and Portugal, sugar-dusted ring-breads come in the form of crowns or plaits with whole eggs tucked in the links. Although real eggs continue to play a central role in regions where the Easter traditions remain more or less unaltered, with the advent of moldable chocolate—a convenient material for sculpting and particularly popular with the sweet-toothed northern Europeans—eggs and baby animals as well as the Easter bunny, a reminder of Eostre’s hare, began to appear in molded chocolate as Easter treats for children.

Sweetness shared not only confers a blessing on all who celebrate the risen Christ but also serves as a reminder of the need to restore fertility to nature, earth, and man.

See also butter; Cadbury; chocolates, filled; cream; eggs; holiday sweets; marzipan; and middle east.

See pastry, choux.

egg drinks go far back in time. Drinking raw eggs straight from the shell as a fortifier is undoubtedly as old as human beings themselves. With time, however, culinary refinement set in, and a whole family of egg drinks developed, in Europe consisting of many versions of hot and cold alcoholic drinks in the style of posset—hot, spiced milk curdled with wine or ale, with eggs later added. Caudle might be the earliest version, with the first recipe dating from early-fourteenth-century England. Thickened with bread as well as egg yolks, it is hardly a drink as such anymore but is very much a restorative, once favored for invalids and women in childbirth.

The most popular egg drink today is arguably eggnog. The name might be derived from egg and grog, the latter originating in the British Navy in 1740 as rum mixed with water. Once popular year-round as an individually prepared drink, eggnog in the English-speaking world today is mainly associated with the winter holidays and is often prepared in large quantities for a group. It typically consists of egg yolks, sugar, spirits (rum, brandy, vodka, or whiskey), milk, and cream, although some recipes add the dairy components immediately prior to consumption, after the sweetened base has aged. Aging for a minimum of three weeks and up to a year (though most often for the period between Thanksgiving and Christmas, when there is an abundance of eggs before winter) melds the flavors and yields a creamier consistency. Commercial versions (also nonalcoholic) tend to substitute the voluptuous richness of eggs with high-fructose corn syrup, carrageen, and guar gum. Despite ongoing health concerns regarding the consumption of raw eggs, scientific study has shown that using alcohol in the aging process kills salmonella, making aged eggnog potentially safer than a fresh version.

Many eggnog variations exist in the United States and elsewhere in the world. According to Myra Waldo’s Dictionary of International Food and Cooking Terms (1967), residents of Wisconsin and Minnesota enjoy the Tom and Jerry, “a hot, frothy alcoholic drink made with beaten egg yolks, stiffly beaten egg whites, rum, sugar, boiling water, bourbon, and spices, served in mugs with a sprinkling of nutmeg.” The origin of German Eierlikör or advocaat is said to lie with Dutch colonialists trying to imitate the creamy mixture of avocado (“advocaat”) pulp, cane sugar, and rum they had been offered in Brazil, substituting egg yolk for the exotic fruit. German cookery books in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries offer many variants of egg drinks, among them the lighter Eierwein, egg wine (in its cold version, egg yolks mixed with sugar, nutmeg, and red or white wine), and the feistier Hoppelpoppel (a hot drink of cream boiled with vanilla, lemon zest, and sugar, thickened with egg yolks and given a kick with rum, arrak, or cognac). Today, Eierlikör is mainly consumed as a (delicious) topping for ice cream. In Puerto Rico, coquito calls for coconut milk and rum. Mexican rompope is flavored with cinnamon; Peru’s biblia is made with the local Pisco, a spirit distilled from grapes.

A false friend is the New York soda-fountain drink called egg cream, which contains neither egg nor cream, but is made from soda water, sweet chocolate syrup, and milk. See soda fountain. Created in 1890 in a candy store with a soda fountain on New York’s Lower East Side, it became the city’s iconic drink. See new york city. Its name undoubtedly derives from the egg-white-like foam that develops on top of the soda when the carbonated water hits the chocolate syrup and milk. Along with soda fountains, the egg cream almost disappeared from New York in the 1960s, but it is experiencing something of a revival, and 15 March has been declared National Egg Cream Day in the United States. Finally, cocktails using raw egg merit a mention, such as Silver Gin Fizz (made with gin, lemon juice, sugar, carbonated water, and egg white) or Pink Lady (gin, grenadine, and egg white), which both use the egg white for texture, or Porto Flip, made from brandy and port and egg yolk for flavor and richness.

See also syllabub.

egg yolk sweets, confections made from egg yolks and sugar, are synonymous with Portuguese cuisine. These rich concoctions, which many non-Portuguese find excessively sweet and cloying, are a hybrid between dessert and confectionery that originated in convent kitchens in medieval Iberia. See convent sweets. Although egg sweets are also made in Spain, particularly in the Castilian region that shares much of its culinary heritage with Portugal, it is the Portuguese who elevated the egg sweet to iconic status, developing an extraordinarily extensive repertoire of recipes.

In Portugal during the Middle Ages, food was scarce, and eggs provided an important source of protein. Eggs (from hens, ducks, and other fowl) were readily available, relatively inexpensive, and, at a time when most Europeans spent more than half the days of the year in religious fasting, the devoutly Catholic Portuguese regarded eggs as permissible Lenten foods.

Eggs were also important in other ways. The whites were used in wine making, to clear the wine of lees. Traditional production methods required around eight eggs per barrel; the wine-making quintas (estates) sent the leftover yolks to convent nuns, a practice said to have been initiated by the pious king Philip III of Spain. (A belief still exists in Spanish folklore that a gift of eggs to the Clarissans will help guarantee good weather for a party.) A further surplus of yolks resulted from the inclusion of egg whites in the building material used for church walls and, according to popular myth, in the starch for nuns’ habits. Finally, because egg whites were widely used in sugar refining (which the Portuguese had learned from the Moors), the nuns had ready access to an abundance of yolks. One effective method of preserving so many eggs was to cook the yolks with a large quantity of sugar. Many nuns found experimenting with confectionery a welcome distraction from the routine of contemplative life.

The most basic form of Portuguese egg confectionery is a sweet, thick sauce of cooked egg yolks and sugar called ovos moles (soft eggs) used as a custardlike filling for tarts and cakes, as a dessert sauce or topping, or as a filling for marzipan sweets. See portugal. Fios de ovos, sweet “threads” made by drizzling egg yolks through a sieve into boiling sugar syrup, is another basic preparation used in many different ways, either on its own or as a component of other desserts. Many variations of eggs and sugar exist, often with fanciful names such as “nun’s bellies,” “angel’s cheeks,” and “bacon from heaven.”

In response to the overwhelming power of the Jesuit Order in Portugal and her colonies, the Jesuits and all other male religious orders, except Franciscans with duties in the colonies, were dissolved in the early nineteenth century, and the female orders were allowed to continue only until the natural death of the nuns. During this time, many recipes for sweets moved into the public realm to become part of the culinary repertoire of housewives and commercial manufacturers. Today, a resurgent interest in traditional Portuguese egg sweets has developed, particularly in the many regional variations that are once again being made in convents throughout the country.

Egg sweets and other convent desserts (doces conventuais in Portuguese), often adapted to make use of regional ingredients such as coconut milk and rice flour, are also found in all the former Portuguese colonies, as well as other places with a history of Portuguese influence. See portugal’s influence in asia.

See also flan (pudím); pastel de nata; and thailand.

eggs are one the most versatile ingredients in baking, used structurally for binding, texture, and aerating. Each egg has three parts: the shell, the white, and the yolk. The shell is thin and porous, usually white or brown, occasionally pale blue. The color of the eggshell is a result of the hen’s breed and regional preferences. Inside, all eggs have similar nutritional content, cooking characteristics, and taste. The white or albumen, clear and thick, makes up about two-thirds of the center; it is mostly water with some protein. The other third is occupied by the yellow yolk or ovum, which contains the majority of the fat and protein. Both white and yolk coagulate at temperatures below the boiling point of water, characteristics much exploited to yield interesting textures.

Whole eggs are stirred and gently heated to thicken dishes like custards, creams, and ice creams (overheating causes curdling and failure of the dish). See custard and ice cream. They are also beaten into mixtures for cakes such as fruitcake, and into batters to help leaven them. Beaten egg is brushed over many types of buns and pastries to give the finished item a gilded, soft shine.

The real power of the egg shows when it is used in separated form. The protein in egg whites can be whipped to form an airy cloud that leavens sponge cakes, soufflés, cookies, mousses, and marshmallows. Whipped egg white and sugar also makes frosting for cakes, toppings for tarts and pies, and gently baked, it becomes meringue. See icing and meringue. Care must be taken not to over-whip, as the mixture loses the ability to hold air.

Egg yolks contribute flavor and color to baked goods, but they are most essential in thickening semi-liquid sauces, mousses, custards, creams, and ice creams; in the correct proportions, they give silky textures. They can also be used instead of whole eggs for a richer and denser cake, cookie, or dough. Yolks are also much used in a special category of yemas, egg yolk sweets closely identified with Spain, Portugal, and areas influenced by them. See egg yolk sweets.

Most recipes call for large or extra-large eggs, which have the best ratio of egg white to yolk. For best results, the egg size specified in the recipe should be used. USDA grades refer to the quality of the egg both inside and out, the weight and other qualities influencing the egg’s value. According to U.S. standards, graders hold eggs before bright lights called candling lights in order to gain a visual of the eggs’ interiors. Random eggs are cracked open onto a flat surface so that the interior can be more easily inspected and compared to others from the same hen or group of hens. A fresh, good-quality egg will crack easily on the edge of a bowl with a nice clean break. The white should spread very little, form a beveled oval, and resemble thin, shiny Jell-O. See gelatin desserts. The yolk should be whole, upright, and round. If the egg white is as thin as water and spreads widely without a bevel, or if the yolk breaks or is flat and low, the egg is inferior and will perform poorly.

The finest eggs come from healthy hens that are raised humanely (as indicated by the Humanely Certified emblem on the carton). If farm-fresh eggs are not available, grocery-store eggs should be purchased refrigerated and in a carton to ensure that they stay fresh. The further from the sell-by date, the fresher they are.

Eggs should be stored refrigerated in their carton from 33° to 45°F (0.6° to 7°C)—the carton is designed to protect the eggs from picking up strong odors like garlic through their porous shell. They last up to one month when refrigerated but change slightly as they age. Eggs under a week old are preferred for baking. Cracked eggs will go bad within a day or two and are more prone to attracting bacteria. Discard any cracked eggs found in the carton.

Fresh eggs whip rapidly to their maximum potential and create stronger foam. They should be refrigerated until ready to use because they deteriorate rapidly at room temperature. Although eggs whip faster when warm, they do not whip to their maximum. If warm eggs are desired, they should not be allowed to stand at room temperature. Instead, the so-called Swiss method is used: place them in the top of a double boiler and whisk continuously until they reach warm or body temperature, about 98°F (37°C). Another traditional home method is to soak whole eggs in a bowl of warm water for 10 to 15 minutes; however, warming the eggs makes them more difficult to separate.

To freeze whole eggs, yolks, and egg whites, remove the desired part of the interior from the shell and place it in a tightly sealed container labeled with the date. Although frozen eggs can be stored for four to six months, the quality will be compromised. Thawed egg products should be stored in the refrigerator for no longer than three days, and frozen eggs cannot be refrozen once thawed.

When separating eggs, have two clean bowls side by side. Position the egg over the bowl intended for the whites. Crack the shell gently to form a clean break in the middle. Break it apart evenly into two halves, retaining the egg inside one of the halves. Then carefully pass the egg from one half to the other, back and forth, allowing the white to drop into the bowl below and keeping the yolk rotating between the two half shells. Use the edge of the shell to cut the white away from the yolk if needed. Place the now-separated yolk into the second bowl.

See also marshmallows; mousse; soufflé; and sponge cake.

Emy, M. , wrote the first book entirely dedicated to making ice cream, L’art de bien faire les glaces d’office (The Art of Making Ices for the Confectionery Kitchen), published in 1786 and written for professionals. Although the book is renowned, its author is a mystery. Presumed to be male (in mid-eighteenth-century France, a woman would not likely have been accepted as a professional confectioner and author), Emy is known only by his surname; his first name and dates of birth and death are nowhere recorded. His writing, however, reveals that he was a perfectionist—serious, opinionated, and passionate.

In his book, Emy explained how to make and freeze ices, ice creams, and mousses. He provided more than 100 recipes, some of them unique. Parmesan and Gruyère ice cream, anise mousse, and ice cream flavored with truffles (the fungi) were among his more exceptional ones.

Emy explored freezing techniques, equipment, health issues, and seasonality. Stressing the importance of using the finest ingredients, he explained how to judge them. He included instructions on molding ice creams into the fanciful shapes popular at the time, to resemble, for instance, asparagus and pineapple.

Emy was a pragmatist. Despite his emphasis on fresh ingredients, he suggested substituting jams when fresh fruits were unavailable. He tempered his instructions on making food colorings by warning that, because some people believed they were poisonous, such colorings had to be used judiciously. He disapproved of adding wine or spirits to ice cream but explained how to do so when an employer insisted on it. He could not resist adding that the results would not meet his standards.

Above all, he advised readers to follow his instructions precisely to achieve perfection. Whatever else he may have been, Emy was an unparalleled teacher.

See also confectionery manuals; france; and ice cream.

entremets are today disregarded bit players in the theater of upscale French and French-influenced menus. They appear at the end of the meal and are usually sweet. In the Middle Ages, though, entremets could be either a secondary dish at a meal in a prosperous household or, at royal or ducal courts, elaborate displays and dramatic or musical performances. The late-fourteenth-century Ménagier de Paris has many recipes for entremets, but few are sweetened. They feature meat, especially pork, fish, and eggs, as well as vegetables, but sugar is uncommon, and a meal typically ended simply with nuts and dried fruit with, perhaps, wafers. See dried fruit and wafers.

The fifteenth-century dukes of Burgundy went in for something quite different. At their most splendid banquets, the entremets came between the courses, not between the plates as a literal translation would suggest. They were not necessarily edible. A banquet of three courses (and many dishes) might have as its entremets a short dramatic performance, a display of the host’s castles modeled in butter, or an imitation whale with musicians inside it. Lesser folk might bring entertainment to their tables with more or less suitable diversions that they, too, would call entremets. The guests at a wedding feast (although perhaps not the bride) could be entertained by a depiction of a woman in childbirth; the pious could be edified by a waxen head of John the Baptist on a platter. This robust tradition faded away by the end of the sixteenth century.

The term “entremets” remained but took on a different meaning in the seventeenth century with the coming of service à la française. This was still a two- or three-course meal. However, the emphasis was on laying out all the dishes for a course in a rigidly symmetrical fashion. La Varenne’s Cuisinier françois (1650) and Pierre de Lune’s Nouveau cuisinier (1659) include substantial numbers of entremets that are predominantly savory, as are most of the entremets in later menus, such as in the 1705 edition of Massialot’s Cuisinier roïal et bourgeois. When sweet entremets do occur, they are most likely to be a form of custard or blancmange and appear on the table at the same time as their savory cousins. See blancmange and custard.

The more luxurious cookbooks included woodcuts or engravings showing the many ways that dishes could be arranged to meet the spatial and gastronomical needs of the time. This new system persisted on most upper-class European tables into the early years of the nineteenth century. A fine array of silver, ceramics, flowers, and pièces montées added to the spectacle. Complications proliferated. Thus, entremets made their way onto the patterned tabletop, slipping their way in between the more significant dishes. At times they were present with the hors d’oeuvres, the latter appearing in those days not as preliminary dishes but as minor dishes often placed around the outer edges of the formally arranged service—that is, outside the main works.

From the mid-seventeenth-century onward, a steady stream of French cookbooks appeared in English, often badly translated, bringing service à la française, hors d’oeuvres, and entremets with them. The English took to this new system with enthusiasm. Thus, John Nott tells his readers in his Cook’s and Confectioner’s Dictionary of 1723 that “Blanc-Mangers are us’d in Inter-messes, or for middle Dishes or Out-works.” He goes on to say “then put it up in jelly glasses. These glasses you may set betwixt your plain jelly, or put it in a china bowl for the middle of the dish, or in cold plates for the second.”

Over the course of the nineteenth century, entremets became an almost entirely sweet course of its own, sharing the bottom of the menus with “dessert” and “ices.” There is only a slight remainder of the old mixture in the British “savoury.” By 1938 Larousse gastronomique lists, under entremets, only sweets; the conversion had become complete.

See also dessert; ice cream; and sugar sculpture.

epergnes are pyramidal dessert centerpieces of silver, gilt-bronze, ceramics, or glass featuring containers and baskets for the display and consumption of edible sweets, biscuits, fruits, and condiments. Many were designed with interchangeable elements and branches for candles and were displayed on raised mirrored platforms. A French-sounding moniker of unknown origin, the term “epergne” (sometimes epargne) was apparently coined in England in the early eighteenth century. In France, an epergne was called a surtout de table, girandole garnie, or machine; in Germany, it was a Tafelaufsatz or Plat de Menage, notwithstanding that these terms were not specific to dessert centerpieces and were applied to savory or figural centerpieces as well. Whereas “epergne” is not found in either Joseph Gilliers’s Le cannameliste français (1751) or Henri Havard’s Dictionnaire de l’ameublement et de la décoration (1894), both authors discuss and illustrate the surtout, which by the mid-seventeenth-century had supplanted the medieval standing salt on the princely table. Stefan Bursche, one of the earliest scholars to tackle the phenomenon of table decoration at European courts, also associates the surtout with the tradition of displaying pyramids of fruit at high-style baroque banquets in Italy and France. Both Julius Bernhard von Rohr, in his Einleitung zur Ceremoniel Wissenschaft der Privat-Person (1728), and François Massialot, author of Cuisiner royal et bourgeois (1705), described a surtout as a kind of dormant that remained in place for the entire meal, its containers refilled at intervals with savory foodstuffs and condiments and, finally, with dessert and its accompaniments.

English silver epergnes seem to survive in larger numbers than their French or German counterparts, though the latter are well documented by published engravings and in inventories. Eighteenth-century porcelain centerpieces range from the inventive Asian porcelain versions concocted by European silversmiths to the Meissen models introduced around 1740, which often survive in bits and pieces, the stand in one collection and the containers and cruets in others. Other European manufacturers produced porcelain centerpieces, following Meissen’s lead. A Du Paquier porcelain version in the Hermitage features eight peasants with cups held aloft dancing around an elephant whose trunk was meant to dispense sweet dessert wine. The fragile glass epergnes regularly bestowed, according to archival evidence, by the Republic of Venice on special visitors and foreign princes are mostly lost.

Judging from the property in the Hofsilber- und Tafelkammer in Vienna and in the English royal pantry, epergnes and surtouts remained fashionable and necessary for court dining into the nineteenth century. Some are still employed at state occasions. The 1762 silver-gilt epergne by Thomas Heming in the Royal Collection was the most expensive item in the coronation service of George III. Even more expensive was the epergne designed by William Kent for the prince of Wales in 1745, which was altered by Rundell, Bridge, and Rundell in 1829 by the addition of legs to raise its height. The gilt-bronze Milan centerpiece in the Hofburg in Vienna, a monumental classical revival ensemble made for the coronation of Emperor Ferdinand in 1838, stretches to 30 meters. A Gothic Revival epergne designed by William Burges for the marquess of Bute was manufactured by Barkentin & Krall in 1880–1881 and is in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Epergnes are elaborate centerpieces for displaying sweets, biscuits, fruits, and condiments. Some have interchangeable elements, such as candleholders, for even more dramatic presentation. This striking epergne was made by the London silversmith William Cripps in 1753. image © sterling and francine clark art institute, williamstown, massachusetts. photo by michael agee

In the Victorian era, simpler epergnes emerged for the upper classes, made up of a central raised dish or urn flanked by smaller containers that might be attached or freestanding. In her Book of Household Management (1861), Mrs. Beeton called such stands “tazzas” and instructed: “With moderns the dessert is not so profuse nor does it hold the same relationship to the dinner that it held with the ancients…. The general mode of putting a dessert on table, now the elegant tazzas are fashionable, is, to place them down the middle of the table, a tall and short dish alternately; the fresh fruits being arranged on the tall dishes, and dried fruits, bon-bons, &c., on small round or oval glass plates. The garnishing needs especial attention, as the contrast of the brilliant-colored fruits with nicely-arranged foliage is very charming.”

Eventually, epergnes became de rigueur for lesser tables, unleashing waves of affordable options in various media for every taste and budget. Apart from reproductions of eighteenth-century models and tazzas, elaborate new forms emerged, featuring a central vase or trumpet for flowers flanked by scrolling branches supporting smaller cups, flutes, or baskets. Google “epergne” to see the good, the bad, and the ugly of the Victorian and modern eras—many for sale, if only there were consumers for such by-now-anachronistic dining accessories. Apart from the occasional banquet of state, hotels, restaurants, and tea salons may be the only locations where epergnes are regularly employed today.

See also bonbons; dessert; serving pieces; and sugar sculpture.

See twelfth night cake.

Escoffier, Georges Auguste (1846–1935), a chef whose career spanned the splendors of the Second French Empire, the Edwardian era, and the early twentieth century, witnessed dramatic changes in French culinary fashion during his life. He ushered in many of those changes himself while serving as chef de cuisine and manager of the kitchens at the Paris Ritz and at the Savoy and Carlton in London, working with his friend and partner César Ritz.

Born near Nice, the young Escoffier learned to cook at his grandmother’s side and later apprenticed at his uncle’s restaurant in Nice. He went on to work at the Parisian restaurant Le Petit Moulin Rouge when it was at the height of its fame during the Second Empire. There, he proved his talent as chef to its powerful and wealthy patrons. By the late nineteenth-century’s belle époque, the elaborate pièces montées of Marie-Antoine Carême were considered too old-fashioned for savory dishes, but Escoffier continued to conjure exquisite dessert pièces montées. His most well-known, Pêche Melba, named after the singer Nellie Melba, is still served today. Timothy Shaw (1994) describes Escoffier’s original Pêche Melba—“its poached peaches rising up in a cone of gold from a silver dish … lay between the wings of a noble Lohengrin swan finely carved out of ice and lightly veiled in spun sugar” (p. 143)—as typical of his dessert creations. Another showpiece, Belle de Nuit, was a crescent moon ice carving perched on a larger block of ice that was lit from within by an electric bulb. The whole was draped with spun sugar and “surrounded by a profusion of ice cream and crystallized fruit” (p. 143).

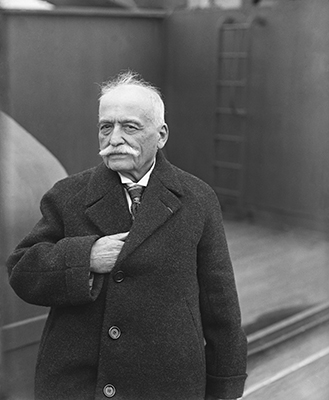

In this 1926 photograph, the French chef and restaurateur Georges Auguste Escoffier is shown standing—rather Napoleonically—on a ship as it arrives in New York. Escoffier codified French cuisine in his masterwork, Le guide culinaire (1903), and his ideas about kitchen management, the use of fresh ingredients, and the proper demeanor of a chef continue to influence restaurant kitchens around the world. © bettmann / corbis

Considering that Escoffier created menus and dishes for the world’s most famous people, including King Edward VII, the duc d’Orléans, and actress Sarah Bernhardt, it is only fitting that a spectacular sweets course would be the capstone of a magnificent meal. His cookbooks, however, reflect his practical nature. Escoffier’s 1903 masterwork, Le guide culinaire, is a classic. In it, he writes that the book’s dessert recipes are limited to the essential elements of pastry, confectionery, and ices that every trained cook must learn. The recipes are not intended for training a true professional pastry cook or confectioner; however, Escoffier believed that every chef should know how to prepare a complete meal (which always included dessert) should the need arise. His menus show that he often incorporated fruits into his desserts, perhaps reflecting his upbringing in the sun-drenched south of France.

See also carême, marie-antoine; fruit; pastry chef; and plated desserts.

Eskimo Pie, a slice of ice cream covered with chocolate, was conceived when an eight-year-old boy in an ice cream shop in Onawa, Iowa, wavered between spending his nickel on ice cream or chocolate candy. The shopkeeper decided to combine the two. The year was 1919, the shopkeeper was Christian K. Nelson, and the resulting confection became the Eskimo Pie.

Nelson made the product by dipping hard-frozen ice cream slices into heated chocolate. Rather than melt the ice cream, the process hardened the chocolate. Nelson called his invention the “Temptation I-Scream Bar” and sold it locally.

In 1921 he and Russell Stover became partners. Stover suggested the name Eskimo Pie. They received a patent for the process in 1922, but it was rescinded in 1929 because coating ice cream with chocolate was not a new idea. It was, however, a wildly popular one. As early as 1922, the partners sold a million Eskimo Pies a day.

Eskimo Pie’s success rippled throughout the ice cream industry and inspired other chocolate-coated ice creams, including the Klondike Bar and the Good Humor Ice Cream Bar. See good humor man. The new products not only increased sales of cocoa and chocolate warmers; they also created a market for ice cream in winter.

Stover left the company in 1922 to concentrate on his candy business. Nelson struggled financially as a result of the patent litigation. In 1924 he sold the company to the manufacturer of its foil wrappers, now known as Reynolds Metals. He worked for the manufacturer until 1961, when he retired.

The company’s frosty graphics feature snow globes, icebergs, igloos, and a cheery boy in a fur-trimmed parka. However, Eskimo Pie is now a controversial name among some Inuit. Today, Nestlé owns the Eskimo Pie brand.

See also ice cream and nestlé.

Eton Mess is a British dessert made of broken meringue, fruit (traditionally strawberries), and whipped heavy (double) cream, mixed together into a sublime combination of textures and flavors. Some recipes include liqueur or a drizzle of chocolate.

Known as Eton Mess since the nineteenth century, the first mention of “Eton Mess aux Fraises” dates to a grand garden party in 1893 described by historian Arthur Beavan. It was attended by Queen Victoria on the eve of the marriage of Prince George, the Duke of York, and Princess May of Teck.

Similar desserts include Lancing Mess (made with bananas), served at Lancing College in Sussex, and Clare College Mush of Clare College, Cambridge University, which Sara Paston-Williams considers “the original recipe for this traditional pudding.” However, the common belief is that Eton Mess was created at Eton College, a boys’ school near Windsor, founded in 1440 by King Henry VI, where many important national figures have been educated. The dessert has many associations with the school: in the 1930s Eton Mess made of strawberries or bananas, with ice cream or cream, was sold at the school Sock Shop (a tuck shop or small grocery). Eton Mess is also served at the longstanding annual cricket match between Eton and Harrow, and at picnics for the school’s 4 June celebrations marking the birthday of King George III, who maintained a close association with Eton.

In 1935 Eton Mess appeared on the menu at Royal Ascot, the famous horse-racing event near Eton; more recently, in 2013, a raspberry and lavender version was served there. Also in 2013, the world’s largest Eton Mess was made in Soho Square in London. It contained 50 kilograms of fresh strawberries, raspberries, and blueberries and fed some 2,000 commuters.

Although the term “mess” may be associated with the messy appearance of the dish, it might also refer to an assortment of people who eat together. The word “mess” could also be used in the sense of a quantity of food, particularly a prepared dish of soft food or a mixture of ingredients cooked or eaten together, as in the term “a mess of greens” used throughout the American South.

See also cream; fruit; meringue; and united kingdom.

evaporated milk is milk from which the water has been partly removed. Because several canned products originally sold as “evaporated” and “condensed” milk are condensed through a process of evaporation, they have historically been surrounded by greatly confused terminology. Today, thick, syrupy, “sweetened condensed milk” is always made with added sugar, while the more fluid “evaporated milk” is produced by condensation/evaporation without added sweetening. In cookbooks published between about 1885 and 1940, however, it is often difficult to know which of the two is meant. See sweetened condensed milk.

Various forms of milk evaporated by long cooking have been used in India for centuries. But modern canned counterparts were technically far more difficult to manufacture than sweetened condensed milk. The latter, introduced in 1861, benefits from the preservative action of sugar. The Swiss-born pioneers of the unsweetened product, John B. Meÿenberg and Louis Latzer, began wrestling with the manufacturing process in 1884. Not until the early 1890s were problems of spoilage or unwanted clotting satisfactorily solved by the firm they had founded in Highland, Illinois, the Helvetia Milk Condensing Company (later Pet, Inc.). On the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, in 1898, Helvetia obtained a contract for supplying canned milk to the U.S. Army in Cuba and the Philippines. It was a major boost for both the company and the public image of unsweetened preserved milk. See spanish-american war. In 1909, manufacturers solved the product’s strong tendency to separate by homogenizing the milk, the first large-scale application of this process to any commercial form of milk.

Like sweetened condensed milk, the new product was far easier to store and transport without refrigeration than fresh milk. It had, and still has, a certain “cooked” flavor resulting from the caramelization of lactose. But if diluted with an equal amount of water, evaporated milk was more similar to fresh milk than the thicker, more syrupy sweetened condensed milk. If used undiluted, it was about as heavy as the “rich milk” or “top milk” (i.e., natural cream layer) that rose to the top of unhomogenized whole milk, and it soon became popular for some of the same uses as cream. Combining it with sugar in coffee, tea, or most desserts partly masked the caramelized note by allowing it to blend with other sources of sweetness.

The Evaporated Milk Association, founded in 1923, vigorously promoted the uses of evaporated milk in cooking, especially for desserts and sweets. In a series of recipe booklets the association gave methods for whipping chilled evaporated milk (with or without the aid of gelatin) to a simulacrum of whipped cream, or for using it in ice creams, frozen mousses, dessert sauces, puddings or pie fillings, pastry doughs, cakes, candies, and sweetened punches like eggnog. Recipes clearly inspired by the association’s suggestions appear in many cookbooks of the 1930s and 1940s, including The Joy of Cooking, and in various compendia published by newspaper or magazine test kitchens. Evaporated milk is still favored by many cooks for making pralines, fudge, and caramels. See caramels; fudge; and praline.

The first successful versions of evaporated milk were at least as expensive as fresh milk or cream, but throughout the twentieth century the price dropped enough to turn the tables. By the 1950s and 1960s evaporated milk had been around long enough for many consumers to prefer it to uncanned milk on grounds of taste as well as economy. However, a period of campaigns against full-fat dairy products was then setting in. In response, during the late 1960s manufacturers introduced reduced-fat versions of evaporated milk. Today it is sold in whole-milk (3.25 percent milk fat), reduced-fat (2 percent milk fat), and nonfat versions. The consistency is often bolstered with carrageenan.

In the last several decades, U.S. sales of both sweetened and unsweetened canned milk have declined. Some of the slack has been picked up by immigrant groups, especially from the Latin American and Far Eastern tropics. Like sweetened condensed milk, unsweetened evaporated milk caught on in those regions without having to face any cultural prejudices in favor of dairy products genuinely or supposedly fresh from the farm; today it is prominently sold in U.S. neighborhood grocery stores catering to Latin American and Southeast Asian clienteles. In the eclectic culinary climates of both areas, it is sometimes combined with sweetened condensed milk.

Evaporated and sweetened condensed milk figure together in shortcut versions of kulfi, the rich Indian ice cream traditionally made with heavily reduced milk. In Hong Kong evaporated milk is now de rigueur in the filling for egg tarts (dan tat or don tot), a slightly anglicized offshoot of the pastéis de Belém brought by the Portuguese to nearby Macau. Guangzhou- and Hong Kong–style dim sum parlors often include evaporated milk in jelled almond “curd” (xingren doufu), the steamed sponge cake called ma la gao, and sweet fillings for some of the flaky pastries generically known as su bing.

See also china; cream; india; milk; pastel de nata; and rombauer, irma starkloff.

extracts and flavorings for preparing sweet confections and baked goods are essences drawn out from plant material that intensify and enhance the food and drink we consume.

Various means are employed to extract elements from the seeds, roots, stems, skins, juice, and blossoms of plants. These elements are then concentrated into essences, syrups, and oils, or into solids, which need to be pulverized. Many of these methods were used in the ancient world and are basically simple: simmering and boiling in liquid; pressing and squeezing; steeping, infusion, and maceration. Distillation is more sophisticated, as it requires boiling a liquid and then, by means of an enclosed vessel—a still—catching its vapor, which condenses into a purer form, or essence. The Greeks, Egyptians, Arabs, and Chinese understood this process as long as two millennia ago and used it much as we do today, to make alcohol, medicine, and perfume in addition to essences for flavoring.

Citrus

Lemon and orange, and to a lesser extent lime and grapefruit, are much used for flavoring. The zest of citrus fruit—the outer, colored part of the rind—contains its essential oil, which is highly aromatic, far more than the juice within. Pared or grated, zest brings liveliness to any concoction, whether savory or sweet (just be sure to avoid the bitter white pith). The cook can also rub a lump of sugar against the outside of a lemon or orange, for the sugar to absorb some of its oil. Another method, when making sweet bread, is to rub one’s hands against the fruit and then immediately knead the dough to impart some of the oil’s delicate fragrance.

The best commercial citrus oil is cold-pressed from the rind, which yields more intensity than extract or flavoring. Because of the large quantity of fruit needed, it is commensurately more expensive. The essential oil of the bergamot orange flavors Earl Grey tea.

Other Fruits

Fruit essences are made from the juice of certain fruits, especially strawberries, raspberries, and pomegranates, which are useful as flavorings for fruit compotes, pastries, and cocktails and lend an appealing pink tinge. The beautiful pomegranate, native to Persia, appears in ancient Greek, Hebrew, Egyptian, and Arab mythology and is still important to the cuisines of the Middle East and the Mediterranean. Fresh pomegranate juice can be concentrated and sweetened to make grenadine syrup to color and flavor cocktails.

Flowers

Orange flower water (orange blossom water) is distilled from the blossoms of the bitter orange. Used for compotes, puddings, pastries, and occasionally savory foods, orange flower water was the main flavoring in Europe before vanilla became available. It is still widely used in the Middle East.

Rosewater is more delicate than orange flower water. Both the water and essential oil are used in the Middle East, Balkans, and India for puddings, pastries, sorbets, and confectionery, including Turkish delight. See flower waters.

The calyx or sepals of the hibiscus blossom are steeped like tea or sweetened into a deep red, sweet-and-sour syrup that is consumed in the Middle East and North Africa. With the rise of specialty cocktails, hibiscus syrup has become popular in the United States.

Nuts

The fruit of the almond tree has long been valuable in the cooking of Europe and the Middle East. The almond is also important for its oil, which comes primarily from the bitter almond (not cultivated in the United States). Almond extract or essence, used in desserts and baking, is processed and distilled from the residual crushed kernels of bitter almonds. Because the strongly flavored kernels contain toxic prussic acid, they must be heated before being eaten in any form. See nuts.

Peaches, apricots, plums, and cherries are all cousins of the almond, so they have a natural affinity for one another. Noyau is a French extract made from the kernels of these fruits, which can be processed into a syrup or liqueur. Macarons are flavored with almond extract, but for amaretti di Saronno an extract of apricot kernels is used. See macarons.

Many sweet beverages are flavored with ground almonds, such as French orgeat, Latin American horchata, and British ratafia, all with traditions reaching far back in time. Hazelnut, walnut, and pistachio nuts are also processed into highly refined oil for baking.

Roots

Licorice (“sweet root”) is the most popular root flavoring. Extract from the long taproot is sweetened with sugar and made into confections and candies with a distinctive black color. The licorice produced in the Netherlands and parts of Scandinavia is much stronger than American “lickerish,” which is closer to candy. See licorice.

Sarsaparilla, from the root of the South American smilax plant, is a soft drink enjoyed in the American South. Root beer and birch beer are other soft drinks flavored with root extract.

Salep, a powder derived from the tubers of the Orchis genus of orchids, flavors milky drinks, custards, and ice creams. It is popular in the Middle East.

Seeds

Kola (cola) is made from the nut, or fleshy seed, of the kola tree. While initially bitter, the taste becomes sweet as it lingers on the palate. In its native West Africa, kola is chewed fresh, or else it is dried and crushed to make cola drinks. Kola contains a small amount of caffeine. American carbonated colas such as Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola belong to this family, however distantly. See soda.

Stems

Mastic comes from the twigs of a shrub that, when cut, ooze a sticky resin. See mastic. The solidified resin is crushed and sweetened to make a flavoring and syrup. In the Balkans and Middle East, mastic is enjoyed in drinks, ice cream, chewing gum, and various candies like Turkish delight.

Leaves

The menthol in leaves of the mint family is highly aromatic. Peppermint is strongest, and its oil is extracted for use in candies and jellies, as well as toothpaste and pharmaceuticals. Spearmint more often flavors juleps, Middle Eastern tea, and fruit compotes. Corsican mint is the chief ingredient in crème de menthe liqueur.

Leaves of the rose geranium plant (Pelargonium or cranesbill) have a rose scent and were often used in the past to infuse desserts. Rose geranium can also be distilled into an essential oil.

The finest extracts and flavorings use natural products without synthetic additions or substitutes, and thus they are costly. Beware of products that seem surprisingly inexpensive. All flavorings should be used sparingly, especially oils and extracts, so as not to overseason food. The cook can always add more but cannot subtract.

See also lokum and middle east.

extreme candy describes overwhelmingly hot or sour candies marketed to consumers with an underlying dare: “This product may be too much for you to handle.”

The Ferrara Candy Company is responsible for three classic early examples of extreme candies that are considered tame by today’s standards. In the 1930s Ferrara introduced Red Hots (originally “Cinnamon Imperials”), small red cinnamon candies made by cold panning. See panning. The far spicier Atomic Fireballs followed in 1954—individually wrapped red jawbreakers that start out mild and quickly become hot and cinnamony thanks to cinnamaldehyde (the active ingredient in cinnamon) and capsaicin (a compound found in hot peppers). And in 1962 Ferrara introduced Lemonheads, hard lemon candies coated in sour sugar.

Children of the 1980s may remember DareDevils, jawbreakers that alternated rings of hot and cool flavors. Willy Wonka Brands (then owned by Chicago-based Breaker Confections) launched DareDevils in 1982 as a “Devilishly Hot” version of their popular Everlasting Gobstoppers. DareDevils have since been discontinued, but their insouciant name lives on in Dare Devils Extreme Sour Candy, sold both as individually wrapped hard candies and liquid sprays in flavors like “Death Drool.” Made by the Foreign Candy Company, Dare Devils owe their extreme sourness to citric acid, malic acid, and sodium citrate.

Warheads, sour hard candies invented in Taiwan in 1975, were first distributed by the Foreign Candy Company in the United States in the early 1990s. See hard candy. The challenge with Warheads is to get past the first intensely painful ten seconds; malic acid coats only the outside of the candies, leaving the more manageable ascorbic and citric acids behind for a mild finish. Children compete to see who can hold the most Warheads in their mouth for the longest time, and the still-popular Mega Warheads now carry the warning “Eating multiple pieces within a short time period may cause a temporary irritation to sensitive tongues and mouths.” Label warnings notwithstanding, competitive consumption is part of the brand identity of many extreme candies. Toxic Waste Candy, similar to Warheads but with a sour liquid core to complement the sour exterior, has a challenge written onto each plastic waste-drum container: “How long can you keep one in your mouth?” A person who can manage 60 seconds is deemed a “Full Toxie Head!” But those who last under 30 seconds are labeled “Cry Baby!” or “Total Wuss!” Toxie Heads prove their mettle by posting YouTube videos of themselves keeping the candies in their mouths for the requisite minute or longer.

One issue with sour candies is that they are terrible for the teeth because enamel begins to break down at pH4, and most sour candies are at least a pH3. The problem is compounded with extremely sour candy; Warhead Sour Spray is a 1.6 on the pH scale, only about 0.6 less acidic than battery acid (though pH scales are logarithmic). See dental caries.

In an attempt to make the world’s hottest candy, several companies have turned to the hottest chile peppers. ThinkGeek, an online retailer, makes Ghost Pepper Super Hot Candy Balls from scorching-hot bhut jolokia, better known as ghost pepper, and Trinidad scorpion pepper. Vertigo Pepper Candy, a product of the appropriately named Bhut-pepper Company in Brooklyn, New York, contains five different chile peppers and measures 2 million Scoville heat units (SHUs), hundreds of times spicier than jalapeños. Although hot and sour tastes guarantee mouth burn, they do not necessarily translate into lucrative sales, for today’s children seek ever more radical candy experiences. Thus, the most popular extreme candies are also interactive, with battery-powered delivery systems and all sorts of special effects.

See also children’s candy and gag candy.