See cocoa.

Cadbury is the trademark representing the large manufacturers who dominated chocolate production in the twentieth century in the United Kingdom and a range of countries formerly part of the British Empire. In 1824 a Birmingham-based Quaker, John Cadbury, opened a shop selling tea, coffee, and “Cocoa Nibs, prepared by himself, an article affording a most nutritious beverage for breakfast,” as he proclaimed in his first advertisement. Cadbury would have remained an obscure retailer had he not seen the potential for expansion afforded by the government slashing the then-crippling import duties on cacao beans, an opportunity he seized in 1831 when he switched to manufacturing and opened his first factory.

Although Cadbury’s timing had been ideal, his range of generic cocoas offered nothing new or different than those provided by Britain’s leading cocoa firm, J. S. Fry & Sons. By the early 1860s, when Cadbury handed over control to his two sons, Richard and George, trade had withered away, losses had mounted, and the end seemed inevitable.

The company was saved by an attribute of George’s that became one of the company’s leading characteristics: a willingness to borrow and exploit a good idea when he saw one. “It was no use studying failure. I wanted to know how men succeeded, and it was their methods I examined and, if I thought them good, applied” (Gardiner, 1923, p. 24), he explained later in his life. The success in question was a much-improved cocoa produced in Holland by Coenraad Johannes van Houten using a hydraulic press, one of which George Cadbury purchased to produce a new brand, Cadbury’s Cocoa Essence. See cocoa and van houten, coenraad johannes.

Cocoa Essence would become Britain’s leading brand of cocoa thanks largely to Cadbury’s most un-Quaker-like competitive streak: George Cadbury lobbied the British parliament to ensure that only his Cocoa Essence brand could be labeled “cocoa.” His rationale was that the competition’s cocoas contained fillers such as flour, sago, or tapioca, whereas the hydraulically pressed Cocoa Essence was “100% Pure, Therefore Best,” an advertising slogan the firm hammered away at for 40 years. While Cadbury’s legal bid failed, the message seeped through to the public’s consciousness.

By the 1900s, the company was being run by the next generation of family members: Edward, William, George Jr., and Barrow Cadbury, all of whom had inherited the borrow-with-pride philosophy. Following the invention of the milk chocolate bar, Cadbury decided which of the versions turned out by a host of Swiss firms was the best, and then copied those milky characteristics to launch its own version, Cadbury’s Dairy Milk, in 1905. See candy bar.

Much impressed by a visit to Henry Ford’s production lines in Detroit, the company revolutionized the British chocolate market between the two World Wars by investing heavily in mass-production technology. It then ploughed the cost savings into a series of price reductions that, when applied against Dairy Milk and a range of new brands such as Fruit & Nut and Wholenut, gave Cadbury a dominant position in the British market. Between 1920 and 1938, Cadbury cut its prices by 70 percent, making chocolate an affordable everyday treat for all, a strategy that increased sales fivefold. During this same period, Cadbury absorbed its great rival, J. S. Fry & Sons, makers of Fry’s Turkish Delight and Fry’s Chocolate Cream (the world’s oldest brand of chocolate bar), and drove another competitor, Rowntree, to the brink of extinction.

This stunning success funded Cadbury’s next great initiative. To protect its export markets threatened by rising import tariffs, Cadbury built factories in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Ireland, South Africa, and India, the running of which they left largely to local management, who built commanding market positions while Cadbury’s major international competitors remained largely excluded.

Following World War II, Cadbury’s U.K. business went into relative decline as its competitors adopted strategies that avoided head-on competition with Cadbury, creating new market segments in which Cadbury held no inherent advantage. Coupled with an increasingly conservative management style, this shift would result in Cadbury losing its market leadership in Britain by the late 1970s.

In 1969 Cadbury, having become a takeover target, merged with the similarly threatened soft drinks firm Schweppes. The growth strategy for both categories was acquisition to fill glaring geographic gaps in the company’s global presence—the chocolate side had barely expanded beyond its interwar markets, while the soft drinks side was missing out on the vast American market.

The drinks gap was plugged by the acquisitions of Dr Pepper and the U.S. rights to 7Up, but no such blockbuster moves occurred in chocolate. Instead, the company accumulated a large number of local and regional companies, such as France’s Poulain and Poland’s Wedel. Lacking big chocolate takeover targets, the company moved into candy with the acquisitions of Trebor and Bassett’s and subsequently chewing gum with its 2002 purchase of Adams Brands, which temporarily made Cadbury the world’s largest confectionery company.

This moment was to be its high-water mark. In the early years of the twenty-first century, the company came under pressure from activist shareholders calling for the confectionery and beverages businesses to be separated. Cadbury succumbed to the pressure, progressively selling and spinning off its soft drinks businesses. This action left the remaining confectionery business more vulnerable to takeover, a fate that befell Cadbury in 2010, when Kraft Foods gained control of the company.

Kraft subsequently reorganized, forming a new company based on its confectionery and snack brands, Mondelēz International Inc., where Cadbury now resides alongside two of its fiercest competitors from a century ago, Suchard and Tobler.

café means more or less the same thing virtually anywhere in the world: a place to drink coffee or another hot beverage, or perhaps even a cold drink—sometimes alcoholic, sometimes not. Most cafés offer snacks, if not full menus. The original idea, however, was subtly different.

The distant origins of the café lie in the coffeehouse and the coffee craze that gripped Europe in the seventeenth century, a fact reflected in French and Italian, whose individual words for “coffee,” “coffeehouse,” and “café” are identical. The late Henri Enjalbert, an eminent French geographer and oenologist, was perhaps the first to speak of a “drinks revolution” in the seventeenth century, which led not only to the refinement of claret, cognac, and champagne as we now know them but also to the discovery of coffee, tea, and chocolate by Europeans. See chocolate, post-columbian and tea.

In Vienna, anecdotal history dates the city’s passion for coffee to 1683 and the Turkish siege. See vienna. As the story goes, the Ottomans abandoned their sacks of coffee in their retreat, and a Serb called Kolschitzky brewed up the beans and addicted the Viennese to coffee at the sign of the Blue Bottle. In fact, the first recorded coffeehouse had opened a generation earlier: in Oxford, England, in 1652. That same year another was opened by the Armenian Pasqua Rosée in the City of London. Another ethnic Armenian, Johannes Diodato, was a pioneer in Vienna, too, after emigrating from the Ottoman Empire.

At the restoration of the English monarchy in 1660, coffee’s popularity increased, and the coffeehouse became a center of social life. It may be that, unlike the taverns of the time, a more sober atmosphere was bred by the absence of alcohol on the premises, although this changed when some coffeehouses began to double up as emporia and “punch-houses.” See punch. In Queen Anne’s time there were as many as 500 coffeehouses; from Ned Ward’s Wealthy Shopkeeper (1706) we know that “every respectable Londoner had his favourite house, where his friends or clients could seek him out at known hours.”

In London, coffeehouses were above all meeting places, as the Wealthy Shopkeeper reveals:

Remember John,

If any ask, to th’ Coffee House I’m gone.

Then at Lloyd’s Coffee House he never fails

To read the letters and attend the sales.

The maritime insurance market Lloyds started out as Lloyd’s Coffee House in Tower Street around 1680, moving to Abchurch Lane in 1682. Coffeehouses also fathered gentlemen’s clubs. The most exclusive and aristocratic club, Whites, was founded in 1693 as White’s Chocolate House. It is the sole survivor of a seventeenth-century coffeehouse. Three centuries ago the political coffeehouses—Cocoa Tree, St James’s (with its inner room for political discussions), Will’s, the clerical Truby’s or Child’s, the scholarly Grecian, and so on—were just as well known. The coffeehouse was not just a place to consume coffee, tea, or chocolate (all heavily sweetened) and talk; it was a place to play card games like piquet and basset.

In the United Kingdom, coffeehouses metamorphosed into clubs or were replaced by pubs. The last native British institution was the Domino Room in the old Café Royal, which closed in 1923. Until recently, Dublin could offer a genuine coffeehouse in the form of Bewleys, where you might run into le tout Dublin, but it has been deserted by its regulars and is now just a tourist trap. There are plenty of continental-style cafés in London, but the contemporary iteration of the native British café, or “caff,” has distorted the original meaning of the place: these informal eating houses serve a variant on breakfast throughout the day. There is seldom wine, and most people drink tea from mugs. The Parisian coffeehouse or café is nearly as old as its London counterpart. Le Procope at 13 rue de l’Ancienne Comédie was founded in 1670 by the 20-year-old Sicilian nobleman Francesco Procopio dei Coltelli, who sold coffee imported by two Armenians called Pascal and Maliban. At the time, the preferred term for the Parisian purveyors was limonadier, since they sold both cold and hot sweetened beverages. Sweet snacks were also on offer. Until 1675 Le Procope was in the rue de Tournon, where it was a signal success. The café moved to its present location in 1686 to be opposite the original Comédie-Française and henceforth attracted a crowd of theatergoers. In the eighteenth century Procope was frequented by wits and became the veritable “oral newspaper of Paris.” Later, the Encyclopédistes—Voltaire, Diderot, d’Alembert—made it a home away from home. Procope was popular with Revolutionaries, too, but by then most had gravitated toward the Palais Royal, the Café de Foy, and the Café Anglais (the latter became the restaurant Beauvilliers). The famous lawyer and gastronome Brillat-Savarin met his friends at the Bonapartist Café Lemblin, while habitués fought pitched battles with royalists in the Café de Valois next door. Procope was closed from 1890 to 1940 and is now chiefly frequented by bus parties. Most Parisian cafés, however, had already departed from the original idea of a coffeehouse and begun to serve an extensive menu. The original idea can still be found, however: cafés such as the Flore or the Deux Magots in Saint-Germain-des-Prés are still true cafés, even if their coterie is now diluted by tourists. Some lovely cafés have also survived in the French regions, notably the Empire-style Deux Garçons in Aix-en-Provence.

Italy, too, has its famous cafés, such as the Caffè Florian in Venice, dating from 1720, or the Caffè Greco in Rome, founded in 1760, which still looks the part and is a magnet to artists and writers even if they are generally outnumbered by tourists.

The list of notable cafés is endless: Madrid’s Gran Café de Gijón, Oporto’s Majestic, and the now sadly mothballed Café A Brasileira.

The coffee craze was slow to cross the Rhine, but the most famous coffee music of all time was composed to commemorate Zimmermann’s Coffee House in Leipzig 80 years after the first cafés surfaced in London. Johann Sebastian Bach wrote his Coffee Cantata to words by Picander (Christian Friedrich Henrici) about a young girl’s coffee addiction:

Ei wie schmeckt der Coffee süße,

Lieblicher als tausend Küsse,

Milder als Muskatwein.

[Oh how nice this coffee is,

Better than a thousand kisses,

Sweeter than Muscat wine.]

Today, opposite Bach’s Thomaskirche in Leipzig, a café commemorates one of the composer’s few light-hearted works.

In the 1840s, Karl Marx’s friend Ernst Dronke made a study of Berlin cafés: he thought Kranzler, which then served only chocolate, the best. After the war Kranzler moved to the Kurfürstendamm and became quite the dullest café in Berlin, if not in Germany. The Romanische was the café of reference for a later generation, taking over as the city’s bohemian haunt from the Café des Westens with its artists’ table. The café, called “Romanesque” because it was part of the architectural scheme around the Memorial Church to Emperor William, was big enough to divide down the middle with “swimmers” and “nonswimmers” “pools” (rooms)—the former for the artists, the latter for the gawkers. Habitués had their own language: auf Pump (keeping a tab); Nassauerei (staying all day on the strength of one coffee); and Ausweis (banishment). The Romanische was destroyed by Allied bombing in 1943. The enormous Café Luitpold in Munich was the place to be seen before it suffered the same fate as the Romanische. Hitler favored the intimate Café Heck, where he would sit surrounded by his thugs. The building is still there, even if it denies previous association with the Führer.

Sometimes the lure of particular cakes has assured the fame of a café, like Gerbeaud in Budapest or Kreutzkamm on the Altmarkt in Dresden, which still makes the best stollen. See stollen. The real guardian of the café concept is Vienna, however, for only in Vienna do the Kaffeehäuser (coffeehouses) remain true to the original idea of an “extended drawing room.” In Britain, the place for locals to gather is the pub; in Germany, the Kneipe; in France, the bistrot. In Vienna, people seek admission to the Stammtisch or regulars’ table at their chosen café or Stammcafé. Admission requires a good relationship with the owner, but also with the waiters, who wield considerable power. If the waiter (Ober) does not know you, you can wait a long time for your Mokka (black coffee) or Melange (half and half), which always comes on a shiny metal salver with a glass of water and sugar cubes. Most drink their coffee sweet. Once the waiter knows you, however, the coffee arrives before you have even ordered it.

You can have a beer or a glass of wine in a Viennese café, too, and most offer some sort of food—particularly cakes—even if serious food is generally found elsewhere. Once you have something to eat, the coffeehouse world is yours: a warm place to sit, free newspapers, somewhere to meet your friends—and all for the price of a coffee.

All Viennese cafés have seen better times, and many have gone into inexorable decline. Too polished an appearance is generally a sign that the coffeehouse is no longer frequented by locals and has become the province of Zuagraste—outsiders—as have the Central, Schwarzenberg, Landtmann, and Mozart, to name just a few. To get the feel of a Viennese coffeehouse today, you must try Hawelka, Bräunerhof, or Prückel. This is a sad fate for the Central in particular: not only is it visually perhaps the most extraordinary café in the world, but it also has a distinguished history as a literary haunt, like the Procope in Paris or the Café Royal in London. Writers, however, vote with their feet: men like Karl Kraus and Peter Altenberg (who wrote a list of 10 pretexts for going to the café) deserted the Central for the Herrenhof, where they were joined by Robert Musil, Franz Werfel, and Joseph Roth. The Herrenhof closed in 1960, and what was left of bohemia moved on to the Hawelka.

Emigrants from the coffee-drinking capitals brought the café idea to wherever they settled, whether in New York, Havana, or Rio de Janeiro. One of the loveliest of the New World café’s is perhaps Café Tortoni in Buenos Aires, originally opened by a French settler in 1858. In the United States, New Orleans’s Café des Artistes (founded in 1862) is primarily known for its chicory-laced coffee and beignets (square doughnuts).

Prior to the coffee bar explosion of the 1980s, cafés in the United States tended to cater to specific ethnic groups (Cubans in Havana, Italians in New York) but also to beatniks, hippies, and other bohemians. Greenwich Village spots such as the San Remo Café (as a much a bar as a café) was a gathering spot for Beat writers such as Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, and Jack Kerouac in the 1950s.

Since the 1980s the European café has been reinvented by chains such as Starbucks, as well as by local cafés and coffee bars that often fetishize the coffee-making process. In modern American usage, “café” refers to a casual restaurant where sandwiches or more substantial meals can be ordered. The spirit of the original café is found in what are called coffee shops, which have proliferated across the United States. Drinking coffee has again become so chic that there are now training courses for the baristas, who make specialty coffees according to methods ranging from drip to siphon. Like their European predecessors, the best coffee shops serve as gathering places, although today’s patrons are more likely to remain focused on their wireless devices than to engage in conversation with others.

See also lemonade.

cake is a sweet food, most often baked, that usually contains flour, sugar, eggs, and frequently butter or another fat. It comes in various flavors, shapes, and sizes and is often chemically leavened with baking powder or baking soda. Derived from the Old Norse kaka, the word “cake” entered Middle English spelled as it is today, though it was probably first pronounced KAH-keh.

Cakes in the Ancient World

Ancient cakes—made from bread dough or similarly dense mixtures; sweetened with honey; enriched with eggs, fresh cheese, or oil; and flavored with nuts, dried fruits, herbs, and seeds—likely evolved from early breads. They are thought to have been made with rye, barley, and oat flours as well as wheat flour. Sumerian texts from some 4,000 years ago mention these sorts of baked goods, and Cato describes a similar kind of cake in De Agri Cultura (second century b.c.e) that was wrapped in leaves before baking and served at weddings and fertility rites. See ancient world.

Sixteenth- to Nineteenth-Century Cakes

Heavy, bread-like cakes made from dense mixtures and often still leavened with yeast continued to be made well into the eighteenth century in England. In France, lighter cakes were developing simultaneously, beginning in the sixteenth century with brioche, perceived at the time as more of a sweet product than a bread. Yeast-risen cakes such as the Gugelhupf, sweeter and richer than brioche, and the baba, originally similar to a Gugelhupf (now lighter) and soaked with rum syrup, remained popular. See baba au rhum and gugelhupf. During the eighteenth century in France and Italy, meringues, sponge cakes made with whole or separated eggs, and cake batters based on soft butter or with melted butter added to sponge mixtures became widespread. See meringue and sponge cake. By the mid-nineteenth century, both baking soda and baking powder ushered in an era of American creativity in the development of cake recipes, and chemically leavened butter cakes, devil’s food cake, and many others began to appear. See chemical leaveners. Angel food, a cake of American origin made from only whipped egg whites, sugar, and flour, is the symbol of the nineteenth century’s search for lightness and delicacy in cakes. See angel food cake.

This “slice” of cake is actually a 36 × 24-inch layer cake made for the chef’s own birthday party. The cake is covered and decorated with sugar paste, while the “plate” is made of pastillage. photo © ron ben-israel cakes

Cake Terminology

In American baking terminology, a cake is anything, large or small, filled or unfilled, made from a sweet batter, whether dense or light. In most other Western baking traditions, “cake” is not the general term that it is in American English. In the United Kingdom, a cake is what Americans might call a “plain cake” and usually refers to a dense baked good such as Madeira cake, similar to what Americans might call a pound cake, or to a fruit-laden Christmas cake (U.S. fruitcake). See fruitcake and pound cake. In the United Kingdom, a layer cake is referred to as a “sandwich sponge,” “sandwich,” or by the French term gâteau. See layer cake.

In France, le cake is a loaf-shaped pound cake often enriched with dried or candied fruits. Lately, the French have begun to apply the term to any loaf-shaped, flour-based baked goods; one result is le cake salé (salted cake), a dense savory cake. A layer cake can be a gâteau in France as well as in the United Kingdom, though the same term may also refer to desserts made from pastry doughs, such as the almond-filled gâteau des rois (kings cake or Twelfth Night cake) made from puff pastry, the gâteau Basque made from a sweet pastry dough, or the gâteau Saint Honoré made from unsweetened pastry dough or puff pastry and pâte à choux (cream puff pastry). See pastry, choux and pastry, puff. Delicate layer cakes with rich or soft fillings are also referred to as entremets (desserts).

In German-speaking countries, terminology mostly follows classic South German nomenclature. Plain cakes, those embellished with fresh fruit, or those made from yeast-leavened doughs are referred to as Kuchen. See kuchen. Layer cakes and some rich cakes made from pastry doughs are referred to as Torten, as in Punschtorte, layers of sponge cake moistened with rum punch and filled with apricot jam; Sachertorte, a rich chocolate cake; and Linzertorte, a dense, jam-filled cake that lies halfway between a cake and a pastry. See linzer torte; sachertorte; and torte. A Torte is sometimes mistakenly thought to be a cake or cake layer made without flour, probably because the Viennese baking tradition often uses ground nuts either alone or combined with flour or dry breadcrumbs for Tortenboden or cake layers.

Italian bakers solve the problem by referring to most cakes, as well as to pies and tarts, as torte. An Italian torta may be either a layer cake, as in torta bignè (a cream-filled layer cake covered with tiny unfilled cream puffs or bignè), or an unfilled, denser cake such as an almond pound cake (torta di mandorle). It can refer to a savory pie (torta rustica) or to a sweet one (torta di mele).

Cake Baking Equipment

Straight-sided cake pans meant for baking round cakes and cake layers came into common use during the nineteenth century. See pans. American and British professional and home bakers still use them today; American pans are usually 1½ to 2 inches deep, whereas British ones are deeper owing to the British preference for taller plain cakes. French closed cake pans, about 2 inches deep, have sloped sides and are referred to as moules à manqué (molds for ruined [cake]). The term is said to have originated with a baker who, on removing his butter-enriched sponge cake from the oven, found that the cake had not risen as much as he had hoped and cried, “Le gâteau est manqué!” (“The cake is ruined!”) Recipes for gâteau manqué appear in many French baking collections to this day.

The use of a bottomless hoop for baking cake layers destined to be sliced horizontally and made into layer cakes, as well as for some denser mixtures, persists throughout Europe. Widespread use of the cake hoop, renamed cercle à entremets (dessert circle or ring), occurred during the emergence in the 1960s of la pâtisserie moderne (modern pastry making) spearheaded by the Normandy-born Parisian dessert mogul Gaston Lenôtre. Stainless-steel rings became available in a variety of diameters and depths and were used for molding layer cakes with liquid mousse fillings, as well as for constructing layer cakes finished with denser mixtures such as buttercream or ganache. Use of the rings enabled less skilled finishers to produce cakes that emerged perfectly symmetrical from the oven.

See also breads, sweet; cupcakes; dessert; entremets; france; germany; italy; small cakes; twelfth night cake; wedding; and wedding cake.

cake and confectionery stands for the presentation of these items on the sideboard, dining table, or in a retail environment usually take the form of a circular dish elevated above the surface of the table or display case by a flaring central foot. The form is essentially that of a tazza, a versatile stem vessel with a shallow bowl that functioned from ancient times as a drinking cup, food dish, and display piece. Examples in delicate glass and precious metal, holding biscuits and sweets, may be found in Dutch still-life paintings and Italian frescoes. Another form of confectionery stand is the pyramidal étagère, composed of circular glass, metal, or porcelain dishes of diminishing diameter fixed by a central rod emanating in a handle. Commonly employed for English high tea, étagères were, and still are, made by every porcelain manufacturer in Europe, even if the market for them is not obvious.

Most popular cookbooks illustrate cakes on stands, though the authors do not comment on how to display or serve a cake. Lifestyle gurus, on the other hand, love cake stands. “Our prop house shelves are overflowing with cake stands of every imaginable size, design, color, and material,” writes Kevin Sharkey of Martha Stewart Living. “We love cake stands for not just cakes but to display flowers, votive candles, even Easter eggs. Nothing makes a delicious pie or cake better than a great cake stand.” The cake stand collection of Food Network television star Ina Garten, the Barefoot Contessa, is apparently legendary and has pride of place on the open shelving in her kitchen.

Like cake knives, the modern-day cake stand is probably a Victorian invention. “A party without cake is just a meeting,” once asserted Julia Child. The cake plate or confectionery stand is a superb accessory for celebrating and protecting many forms of sweetness.

See also epergnes and serving pieces.

cake decorating, the art of making cakes attractive with sugar icing, gilding, and other materials, came into its own in the late 1800s, due largely to new technology and societal changes. Decorative confections originated from Renaissance trionfi di tavola, sugar sculptures made to adorn feasts of the wealthy. These sculptures survived alongside ornate cakes on affluent dinner tables into the early 1800s and are used for commercial purposes to this day. See sugar sculpture. However, over the course of the nineteenth century, the growth of a large middle class in Europe and America, along with more reliable ovens and affordable ingredients, led to standardized cake recipes. Some special cakes, such as those made in England for weddings and Twelfth Night, were decorated with sugar paste figures from the late eighteenth century onward. See twelfth night cake; wedding; and wedding cake. It was not long before the cakes’ appearance became as important as their taste, as evidenced by the chromolithographs of decorated cakes in the 1892 edition of Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management. See beeton, isabella.

This rosette, or floral decoration, was made around 1975 by Hans Strzyso, the chief baker at Madsens Supermarket in New Ulm, Minnesota. Strzyso specialized in lavishly decorated cakes and German baked goods. photo by flip schulke / u.s. national archives

Piping and Icing

For a century, however, cake decoration would remain a mostly professional matter, made possible by the 1840s French invention of piping. First extruded from paper cones, then later from metal tubes (also called tips), piped icing made elaborate cake decorating possible for all levels of bakers. With practice—and the help of colored icing and pastry school courses or printed instruction—bakers could now apply elaborate trims directly to the cake itself or attach them when they were dry. Unlike other sugar ornamentation, most piping did not have to be removed before eating.

With the use of metal “nails,” piped flowers blossomed on cakes. Piped letters and numbers produced names and messages on both holiday and personal celebration cakes. Piped “weaves” made two-dimensional or stand-alone baskets possible. Intricate piping created the look of fine lace, especially when it was done on net for added strength.

Originally a German specialty, network became the rage in Edwardian England when émigré confectioners Herr Willy, Ernest Schulbe, and R. Gommez produced publications detailing the method. At one English trade show, a wedding cake covered in piped network was even lit with “small electric lamps” (“a troublesome piece of work,” admitted its creator, Ernest Schulbe). By the 1920s Joseph Lambeth, an English émigré to America, had popularized his interwar variation, overpiping, with its multiple layers of thin stringwork. However, single-layer tortes, piped in vivid colors, had replaced much of the white lace multi-tier look, except for weddings. In the 1930s, when some wedding gowns were colored, all-color wedding cakes became a fad, too. After World War II, Nirvana (the pen name of Ernest Arthur Cardnell) brought the run-out technique of piping to 1950s Britain. This technique literally flooded geometric shapes with icing. Piping was also used to create animal forms (including circus animals) and figures (including dancers and acrobats).

With cake recipes appearing in newspapers and magazines and the introduction of supermarket cake mixes, suburban housewives, especially in the United States, became major practitioners of cake decorating. See cake mix. American firms like Wilton advertised that “every homemaker can learn to decorate cakes—even the most inartistic or unskilled.” Although 1950s plastic ornaments might have been a godsend to some women, so many others practiced true cake decorating that even an independent baking-school owner like Richard Snyder devoted four books to floral piping between 1957 and 1963; the fourteenth printing of his original 1953 manual for amateurs appeared in 1976. See publications, trade.

Meanwhile, Wilton’s books illustrated the company’s own 8-foot-tall cake for the San Francisco Association of Retail Bakers Convention and official seven-tier cake for the Chicago International Trade Fair. For the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair, a sugar company, baking company, baking school, and restaurant chain joined forces to produce and promote the “World’s Largest Birthday Cake,” which weighed 25,000 pounds and stood 23 feet high. The cake was sold as boxed slices to fair attendees.

True creativity stagnated until the 1990s cake-decorating revival that pitted trained professional pastry chefs against amateurs, often art directors or crafts enthusiasts. See competitions. Professionals increasingly concentrated on geometric fantasies—usually inedible and meant as showpieces. Cake decorators increasingly looked to Australia, South America, and Asia for invention. Australian housewives developed the fashion for fondant covering, whereas wildly intricate yet innovative piping was practiced by Indonesians, Filipinos, and Central Americans, whose wedding cakes often occupied an entire table, just when the craze for tiers of cupcakes took Anglo-American cake decorating by storm. See cupcakes and fondant.

Showpieces

Although piping became the dominant cake-decorating method, molded and modeled ornaments, made by professionals from gum paste or marzipan, were highly desirable on sugar showpieces that required longer shelf lives. See marzipan and tragacanth. In the nineteenth century foods of all kinds, not just desserts, were subject to sculpting and molding. Sometimes the ingredients were artificial so that the finished item—while looking good enough to eat—could withstand the wear of display. Instead of being made exclusively for private parties, these showpieces began to appear in professional competitions, at trade shows and public exhibitions, and in shop windows. Despite the change of venue and audience, some continued to have classical shapes—temples, plinths, even a Venus de Milo carved in beet sugar—but their purpose was to promote bakers’ skills. Faux vases, baskets, and pillows became mainstays of shop-window showpieces, but wedding cakes remained the most effective vehicle for cake decoration. A 1923 article in Bakers’ Helper magazine, “Show Pieces That Attract Custom,” featured an enormous five-tier wedding cake that had “been used more than once in the Kunze (bakery) windows.” As time went on, professionals attracted wider attention to their showpieces. W. C. Baker, for example, created a heavily publicized cake for the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition, weighing 1,000 pounds and with tiny models of San Francisco landmarks. Today’s decorating professionals often find television shows the best way to feature their art.

See also dolly varden cake; icing; and pastillage.

cake mix is an icon of American home cooking, a product so deeply rooted in the nation’s culinary culture that when U.S. homemakers say they baked a cake from scratch, most often they mean they used a mix. See cake.

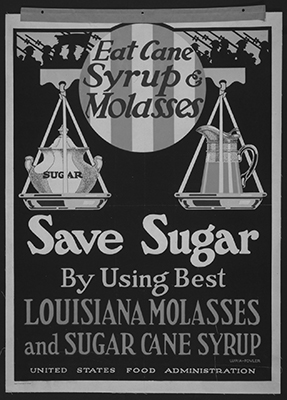

The first cake mix on the market was Duff’s Ginger Bread Mix, which appeared in 1929 and contained dried, powdered molasses as well as flour, sugar, leavenings, and spices. It was developed by P. Duff and Sons, Inc., a molasses company in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, that hoped to boost the sales of molasses. See gingerbread and molasses. The initial response to Duff’s was so positive that the company quickly introduced white, spice, and devil’s food cake mixes. During the 1930s other small companies began producing cake mixes, until wartime shortages of sugar and fat halted production.

Research and development continued, nevertheless, especially at the nation’s major flour companies, and after the war, industry giants such as General Mills and Pillsbury moved directly into the cake-mix business. Sales of flour for home baking had been dropping for years, as fewer and fewer women made their own bread. Here was an excellent way to reinvent flour and charge more for it. General Mills introduced a fine-textured gingerbread it called “Gingercake” (italics in the original) in 1947. A year later Pillsbury introduced a white cake mix and a chocolate fudge cake mix, and by the 1950s some 200 manufacturers were turning out cake mixes. Sales more than tripled from 1949 to 1955. The industry was exuberant and so was the food press. As early as 1949, the popular weekly magazine Collier’s declared that “most housewives” had switched to mixes.

Sales of cake mixes tripled in the post–World War II United States, redefining home baking and spawning an industry of brand-driven cookbooks as Betty Crocker, Duncan Hines, and Pillsbury became household names.

“Most housewives,” however, had done no such thing. True, the early cake-mix business had ballooned rapidly, but according to a U.S. Department of Agriculture study, by 1955 only 4 out of 10 families were using “flour mixes,” a category that included long-established pancake and biscuit mixes, as well as cake mix. Ten years later a food-industry study concluded that “per capita consumption of cake mixes has been virtually stable since 1956.”

Industry experts were puzzled by the slowdown, but an apt assessment of the product appeared in Hilltop Housewife Cookbook, compiled by the New England food journalist Hazel B. Corliss. She had no objection to short-cut cookery on principle, but when it came to cake mixes, she balked. “My late husband, ‘Pop,’ couldn’t abide cake mixes,” she wrote. “I used one once and he insisted that it was only fit for the hens to eat! Prepared mixes usually do not have the good ‘home’ flavor, and they don’t have that most precious ingredient, a wife and mother’s love for her family” (p. 5).

Evidently, the symbolic power of a homemade cake—long seen as the epitome of feminine love and skill—posed a threat to the expansion of the cake-mix market. According to many journalistic accounts of how this problem was solved, manufacturers simply decided to reformulate the packaged mix. They eliminated the dried eggs and required the homemaker to add her own fresh eggs, thus persuading her she was indeed engaged in traditional baking.

This solution, often attributed to studies for General Mills conducted by the consumer-psychology expert Ernest Dichter, is apocryphal. Manufacturers had been pondering the question of whether to use fresh or dried eggs since the early years of cake-mix research. They knew that adding fresh eggs gave the cake better flavor and texture; they also knew that including dried eggs in the mix made it faster and easier to do the work. Surveys showed that consumers were divided as to which approach they preferred. By 1948 General Mills had chosen fresh eggs, Pillsbury had chosen dried eggs, and both companies were market leaders—until the sales of both companies sagged after 1955.

The larger issue suggested by the egg anecdote, however, was significant. Dichter’s research clearly indicated that homemakers were reluctant to forfeit a sense of personal involvement in cake baking. Hence, an emphasis on “creativity” became prominent in advertising: women were encouraged to add oil, pudding mix, spices, and other ingredients to make their cakes more personal. (This also helped to counter the taste of artificial flavorings that often identified a cake-mix cake.) Even more powerful was the new role assigned to decorating. According to innumerable magazine stories, a “creative cook” could transform a cake-mix cake into an elaborate fantasy by deploying frosting, food coloring, candies, and the like. See cake decorating.

These changes in technology and marketing brought about new standards for home baking. Traditionally prepared cakes came to seem inferior to cake-mix cakes, which were invariably light, sweet, and flawless. Today, most American home cooks prefer cake mixes not only for their speed but also for their factory-bred taste and texture, reliably achieved by following the directions on the box.

Canada, in its early history, was a country where sweets tended to be regional, dependent on local ingredients and the origins of new arrivals. By the end of the nineteenth century, the huge nation was largely settled, and the increasing availability of cookbooks influenced the range of sweets that make up what we now call dessert—cakes, small cakes and cookies, pastries, pies, tarts, and puddings. Most recently, new twentieth- and twenty-first-century technologies and the arrival of new Canadians from around the world have further expanded its ever-bountiful sweet table.

When European settlers arrived in the early seventeenth century, they found an already established taste for sweets. In the St. Lawrence River basin and eastern Canada, for example, where maple trees flourish, the Sugar Moon was a time of tribal gatherings and celebrations involving maple products. Members of the First Nations collected sap, then boiled it down using a succession of heated stones. With metal pots the process was sped up. Maple became a distinguishing Canadian flavor. See maple sugaring; maple syrup; and native american.

Maple syrup production grew in the provinces of Ontario, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick, but especially in Quebec, which now accounts for almost three-quarters of the world’s supply. Maple syrup and sugar remain important ingredients in such traditional recipes as grand pères au sirop d’érable (dumplings in maple syrup), tourlouche (maple syrup upside-down cake), and tarte au sirop d’érable (pie with custardy maple syrup, egg, and cream filling). One of the best loved is tarte au sucre (sugar pie), with a cream, butter, and maple sugar filling. An instant maple treat is tartine à l’érable—a slice of homemade bread, with a sprinkle of grated maple sugar and a drizzle of cream. Pouding au chômeur (poor man’s pudding), a famous twentieth-century, two-layer indulgence consisting of cake on top, custardy brown sugar, and often maple syrup underneath, has emerged as the definitive Quebec dessert. In other parts of eastern Canada, backwoods pie (again a maple custard filling), maple cottage pudding, maple fudge, and maple ice cream are old-time favorites.

Another swath of sweetness encompassed much of Atlantic Canada, notably Newfoundland and Labrador. Here, molasses from the Caribbean—traded for salt cod—became the sweetener of choice. See molasses. Molasses buns, made with salt pork, molasses, cloves, allspice, ginger, and raisins, used to be a noon-hour meal for men fishing or cutting firewood in winter. Toutons, pieces of bread dough, were fried and sauced with hot molasses and butter. See fried dough. Molasses was combined with dried fruit and spices in fruitcakes for Christmas and weddings and was also integral to gingerbread cakes. See fruitcake and gingerbread. A Newfoundland specialty, lassy tarts have a molasses, egg, and breadcrumb filling. The most famous Newfoundland sweet is figgy duff with molasses coady. This is a boiled pudding (duff) with raisins or currants (figgy) with a hot molasses and salt pork or butter sauce (coady). Molasses still enjoys prominence in the pantries of eastern Canada, in gingerbread cakes and spiced cookies. Examples are soft drop cookies such as cry babies, or others rolled thick and cut, such as Fat Archies. In Canada’s west, honey is often the choice of sweetener.

Everywhere in Canada, wild berries have figured prominently in sweets. Berries differ from east to west, south to north. Many of Canada’s heritage sweets are based on whichever berry is local and free for the picking. In Newfoundland and Labrador, there are cloudberries, known locally as bake apples, and tart partridgeberries, also known as lingonberries. From the Atlantic to northern Ontario, wild low-bush blueberries are harvested. The land has also provided wild elderberries, strawberries, raspberries, gooseberries, currants, and blackberries for desserts and preserves. In the prairie provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, Saskatoon berries, high-bush cranberries, and various wild cherries are the starting point for sweets. British Columbia is lush with such wild berries as blackberries. Not as well known is the Canadian buffalo berry, also known as soap berry or soopolallieis, which is crushed, sweetened, and whipped to make a frothy treat known as “Indian ice cream.” See akutuq. In the north, foraging for wild berries such as cranberries, Saskatoons, and bake apples is a way of life. Berries found their way into a variety of English- and American-influenced puddings, buckles, grunts, cobblers, and the roly-poly, with the fruit combined in some way with biscuit dough. See fruit desserts, baked.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, cookbooks helped define and popularize sweets. The first English-language cookbook The Cook Not Mad was published in 1831 in Kingston, Ontario. A book of the same title, published a year earlier in Watertown, New York, introduced North American ingredients, including pumpkins, squash, cranberries, and cornmeal, to a largely English repertoire. La cuisinière canadienne (1840) first defined Canadian, or more precisely, French Canadian cooking. Sweet recipes of French and English origin called for ingredients such as pumpkin and cranberries, and included a generous selection of puddings, among them plum pudding and bread pudding. See pudding. “Canada is the land of cakes,” wrote Catharine Parr Trail in 1854 in her book The Female Emigrant’s Guide, an encouraging and practical guide for newcomers. For example, in addition to offering a recipe for apple pie, Traill provides instructions on selecting suitable apple trees, planting, grafting, harvesting, storing, even drying a bumper crop. As for cakes, she wrote, “I have limited myself to such cakes as are in common use in the farm houses” and continues, “A tea-table is generally furnished with several varieties of cakes and preserves.” As evidence, Trail provides a variety of mostly chemically leavened cakes that would have been familiar to cooks across settled North America. See cake and chemical leaveners. Traill put her stamp on the kinds of cakes newly arrived Canadians embraced.

The best-selling English-language cookbook of the nineteenth century was the 1877 Home Cook Book, Canada’s first community cookbook. By 1885, 100,000 copies of it had been sold to a population of 4.5 million. According to culinary historian Liz Driver, the Home Cook Book followed a pattern of community cookbooks recently established in the United States. The Home Cook Book provided a model for women in English-speaking Canada to use their own recipes, and to support good causes such as hospitals, charities, churches, and organizations like the Women’s Institute, a tradition that continues to this day. Its emphasis on sweets set a precedent for subsequent community cookbooks. As in the United States, cookbooks and booklets were created by manufacturers of new products such as baking powder, corn syrup, and cocoa, as well as of established ingredients, such as flour. These publications encouraged the sweet side of cooking. A prominent example is The Five Roses Cookbook, the 1915 edition of which had enormous influence, with sales of 950,000 copies, enough for one in every second Canadian home. The recipes were devoted almost entirely to sweet baked goods and breads, again favoring cakes over puddings, pies, and cookies, but including a small chapter on doughnuts, described as “dainty goodies.” The recipes indicate that Canadian pantries stocked bananas, dates, canned pineapple, shredded “cocoanut,” chocolate, and gelatin in addition to familiar molasses, maple syrup, apples, cranberries (mock cherries), mincemeat, dried apples, rolled oats, raisins, currants, and candied fruit. See candied fruit.

Among the book’s treasures is a recipe for Butter Tarts, admittedly not the first for what some consider the only created-in-Canada dish. That honor, according to culinary historian and researcher Mary Williamson, goes to the recipe in the 1900 cookbook published by the Women’s Auxiliary of the Royal Victoria Hospital in Barrie, Ontario, which contains a recipe called “Filling for a Tart.” Over the next few years the recipe, now named Butter Tarts, reappeared in other cookbooks, such as the Canadian Farm Cookbook in 1911, where six versions exist as collected from Ontario home bakers.

Since Canada’s population was mainly rural at the beginning of the twentieth century, it produced much of its own food, notably baking ingredients—butter, cream, milk, lard, eggs, and fruit. Canadian wheat was considered the finest in the world, as the gold medals it won at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904 demonstrated. By the mid-nineteenth century, cook stoves began to replace hearths and bake ovens. In the twentieth century, in turn, electric and gas ranges made cook stoves obsolete and baking easier. With these new resources Canadians could afford to have dessert every day. And they did, even pie for breakfast. When company was coming, hostesses rose to the challenge by offering generous dessert spreads: a choice of pies, a pudding, a cake, cookies, and preserved fruit. One’s reputation was made when company called; at fall fair baking competitions; in the desserts provided for threshers; and in the pies the ladies brought to community suppers. See fairs.

A significant change in sweets took place with the development of domestic science in the late nineteenth century. Celebrated in this movement was Fannie Farmer. Her influential The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (1896) was widely distributed in Canada. See farmer, fannie. Notable in Canada for disseminating a similarly rational approach to cooking and baking was Nellie Lyle Pattinson’s Canadian Cookbook (1923), originally a university textbook but later a very consumer cookbook that went through many editions. Pattinson’s use of the word “Canadian” helped define Canadian desserts.

It would be hard to find a country anywhere in the world with a more varied populace than Canada’s, or a richer collection of sweets that reflect former homelands. In southwestern Ontario, the Mennonite and Amish communities are celebrated for Dutch apple pie. See pennsylvania dutch. The Mennonites who settled in the west came from Russia. At their afternoon break, faspa, the table often holds a rhubarb, plum, or apple platz—a tender cakey crust with fruit and sweet crumbs on the top. Icelandic settlers in Manitoba retain homeland memories with vinarterta, layers of cake and cardamom-spiced prune filling. See vinarterta. Jewish bakers have added rugelach and hamantaschen filled with lekvar (thick prune or apricot jam) to the sweet table; the Portuguese contributed custard tarts; the Italians gelati and biscotti; South Asians mango kulfi (ice cream) and cashew barfi (fudge). See barfi; biscotti; hamantaschen; and rugelach. Eastern Europeans provided richly decorated Easter breads, honey cakes, buttery crescents, strudels, and tortes; Greeks baklava and sugar-dusted kourabiethes; and Latin Americans tres leches cake and dulce de leche. See baklava; dulce de leche; and tres leches cake. These top picks represent a much wider repertoire, filtered to appeal to already established Canadian ingredients, tastes, and techniques. Baklava appears, but no Greek custard pie, galaktoboureko; Chinese fortune or almond cookies win out over traditionally sweet red bean soup. Just as the sweets of earlier immigrant communities evolved to include pumpkin, Saskatoon berries, cornmeal, cranberries, carrots in Christmas pudding, and maple, so did the sweets of recent arrivals, who add blueberries to their coffee cakes and sauce their panna cotta with rhubarb compote.

Although home baking was widely practiced, Canadians long satisfied their sweet tooth at local bakeries where cinnamon rolls, fruity Chelsea buns, sugar-coated jam doughnuts, and raisin bread augmented everyday fruit and nut loaves, pumpkin pies, raisin oatmeal cookies, and layer cakes. On a larger scale, the Quebec bakery Vachon grew into a national chain, along the way giving the world the snack cakes May West (vanilla sponge-cake layers) and Jos Louis (chocolate layers), both filled with cream and coated with hard chocolate. Prominent also in the sweet snack line is the Whippet, originally Montreal-produced, a vanilla cookie base topped with a round pillow of marshmallow and coated with hard chocolate. Equally part of Canada’s sweet snack repertoire is the doughnut as sold by the very popular Tim Hortons chain, Canada’s largest food-service operator. There, you can buy a Canadian maple-honey cruller and double chocolate doughnut to go with your double double coffee (coffee with two sugars and two creams). See doughnuts.

Today, there are dessert cookbooks to respond to any interest, whether in French or Middle Eastern sweets, shortbread or cake pops, or simply the latest food fashion from the United Kingdom, France, Italy, or the United States. Celebrity pastry chefs and bakeries share their secrets on television shows and blogs. An emerging interest in low-fat and sugar-, gluten-, dairy-, egg- or nut-free products is driving new developments in sweets. Homemade is now simpler—fewer pies and more puddings, squares, and muffins are created. See muffins.

The Canadian love of the dessert course, and especially of baking, lives on. Certain desserts are classics: date squares, self-saucing lemon or rhubarb puddings, blueberry muffins, flapper pie (a meringue-topped custard pie with a graham cracker crust), apple pie, Queen Elizabeth cakes (date slab cake with a broiled coconut topping), oatmeal cookies, Nanaimo bars, banana bread, sugar pie (tarte au sucre), and gingerbread houses. See nanaimo bar. To paraphrase Catharine Parr Traill, Canada is truly the land of sweets.

See also breads, sweet; drop cookies; flour; fruit; pacific northwest (u.s.); portugal; rolled cookies; and united states.

candied flowers are produced by several different methods, depending on whether the whole flower or only its petals are used. For candied petals, what is technically a real “candying” process—the osmotic penetration of sugar, similar to that used for candied fruits—is most common. See candied fruit. For the whole flower, which is too difficult to candy, a crystallization technique, called praliner in French, is used. A third method, sometimes used at home, is to paint flowers or petals with egg white and dust them with sugar.

The use of flowers in confectionery dates back to the medieval Arab world. The flowers were mostly used as ingredients in syrups and sherbets (from the Arabic sharab), as well as in many kinds of perfumed waters, mainly rosewater and orange flower water. See flower waters and sherbet. The origin of candied fruit techniques is definitely Middle Eastern, with candied flowers given the distinctive name of murrabayat, preserves made of pulverized flowers mixed with sugar. In the Western world, the use of flowers in confectionery is first mentioned in the eleventh century, as rose and violet waters for use in fruit preserves and jams. See fruit preserves.

Flowers, in the form of “fake” sugar flowers perfumed with flower essences, featured prominently in the extravagant sugar compositions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. See sugar sculpture. Around the same time, though, a renewed interest arose in the use of “real” flowers in confectionery. In Delightes for Ladies, the English writer and inventor Sir Hugh Plat wrote:

Dip a rose that is neither in the bud, nor over-blowne, in a sirup, consisting of sugar, double refined, and Rose-water boiled to his full height, then open the leaves one by one with a fine smooth bodkin either of bone or wood; and presently if it be a hot sunny day, and whilest the sunne is in some good height, lay them on papers in the sunne, or else dry them with some gentle heat in a close roome.

Plat also offered a more extravagant recipe that describes how to candy rose petals on the bush by pouring syrup over them and letting the petals dry in the sun.

Among the flowers most frequently mentioned as fit for candying are violet, rose, orange flower, marigold, lilac, acacia, mimosa, chrysanthemum, carnation, daffodil, lemon and jasmine, borage, and rosemary. However, only roses, violets, and to a lesser extent orange flowers had historically broad use, becoming part of a candied flower industry that still produces them commercially. Because flowers must be harvested during the night or at dawn to preserve their freshness, and sugared within a few hours, the candied flower artisans (and, later, a few industries) were located very close to flower-growing areas, mostly in Spain, southern France, and the northwestern Italian region of Liguria.

Pietro Romanengo fu Stefano, the famous Italian confectionery company based in Genoa and founded in 1780, still makes candied fruits and flowers in the traditional way, using a proprietary handwritten manual from 1906 that describes the candying of rose and violet petals as follows:

Pick the largest and thickest petals. Bring a sugar syrup to 86°F (30°C). Dip the petals in it and take them out when the syrup starts boiling. Press the petals. Put them back in a 86°F (30°C) syrup and let them rest for 24 hours. Change the syrup and let the petals rest up to one week. Spread the petals to dry and grain them twice with colored sugar.

All nineteenth- and twentieth-century recipes for candied flowers include some tinting of the flowers with natural or artificial colors because flowers when boiled tend to lose their colors (and some of their aroma), which need to be manually restored. See food colorings.

The only flower still commercially candied or crystallized whole is the violet. This flower, usually Viola odorata (known also as Viola di Parma), is preserved by coating it in egg white and crystallized sugar. Alternatively, hot syrup is poured over the fresh flower, or the flower is immersed in the syrup and stirred until the sugar recrystallizes. Violets were formerly an important part of the economy of the southern French city of Toulouse. Originally brought from Italy, the violet-growing business became so widespread in the Toulouse region that in 1907 there were some 400 farms producing 600,000 bouquets a year. The candied violet industry commenced in the nineteenth century to absorb the excess production of flowers. Today, whole candied violets, known as violettes de Toulouse, are made commercially by only one company in Toulouse: Candiflor.

Candied or crystallized flowers are used mainly to decorate desserts. Confiserie Florian, a traditional confectionery company based in a small village above Nice, produces candied flowers but is also expanding the use of candied fruits by creating new recipes. Pietro Romanengo fu Stefano puts whole candied violets in boxes of marrons glacés. Orange flowers in many countries are associated with weddings. Candied orange flowers were once used in Italy as wedding favors, associated with confetti or sugared almonds, but they have been replaced by sugar pastilles flavored with orange flower water. See confetti.

See also cake decorating; chestnuts; pastillage; and wedding.

candied fruit is whole fruit or pieces of fruit preserved with sugar through a series of operations in which the natural liquid of the fruit is replaced by sugar. To some extent, candied fruit has affinities with fruit pastes, marmalades, and jams, but differs from these products in that candying requires a sequence of operations over a week or more. Candied fruit is alternatively known as crystallized fruit or glacé (or glacéed) fruit, depending on the product, the country, and the type of finish, but the process is basically the same: steeping cooked fruit in increasingly concentrated sugar solutions so that, by osmosis, the sugar permeates the fruit and reaches a concentration that will ensure the stability of the final product. Candied fruit is “dry”; it might be sticky, but it does not need to be submerged in sugar syrup for storage, although the earliest forms of candied fruit probably were.

The Romans recognized that fruits could be preserved in sweet syrups; Book 1 of Apicius (a compilation of early Roman recipes) includes recipes for whole quinces stored in honey and defrutum (thick, concentrated grape juice), and for preserving fresh figs, apples, plums, pears, and cherries by covering them in honey, making sure that none of the fruits touched. Although these preparations might have been precursors, candied fruit as we know it today dates from the medieval era, evolving more or less in tandem with progress in sugar technology and with the availability and affordability of sugar.

Arab culture introduced the art of sugar refining to Mediterranean Europe, and probably also culinary techniques using sugar. A thirteenth-century Arab recipe manuscript includes a recipe for candied citron peel using equal quantities of sugar and honey and flavoring it with ginger, long pepper, Chinese cinnamon, and mastic. It is not clear whether the peel was stored in syrup or dried.

Sweet and therefore prestigious, candied fruit was one component of the final course of a medieval banquet. At a reception given by Pope Clement VI in mid-fourteenth-century Avignon, the dessert featured a multicolored array of candied fruits. At this time, when sugar was still relatively scarce and expensive, honey or concentrated grape must could be substituted for sugar; Clement VI and his successor received an annual gift from the town of Apt of “fruits confits avec du raisiné” (reduced must). In his 1552 book of preserves, Nostradamus similarly recognized the interchangeability of sugar, honey, and concentrated must, though he believed that sugar yielded the best results. See grape must and nostradamus.

Fifteenth Century

Possibly the earliest recipe collection devoted entirely to confectionery, the fifteenth-century Catalan manuscript Libre de Totes Maneres de Confits, gives recipes for candied fruits and sweetmeats made with honey and alternative versions of the same using sugar. Significantly, the recipes call for successive boilings of the syrup, whether honey or sugar, before pouring it over the fruit, repeating this process until done: “fins que conegau que sien fets” (literally, “until you know that they are done”). Unfortunately, the recipes do not specify whether the fruits—a great variety, including citrons, oranges, lemons, peaches, apples, quinces, melon, and cherries—are to be stored in the concentrated syrup that, in the final step, is reduced to the “thread” stage, or whether they are allowed to dry. See stages of sugar syrup. In one recipe for candied citron peel (with sugar), however, the final step calls for dipping the peel in a reduced rosewater-flavored syrup and then transferring it to sheets of paper; this process might have produced a thin, brittle sugar shell around the strips of peel.

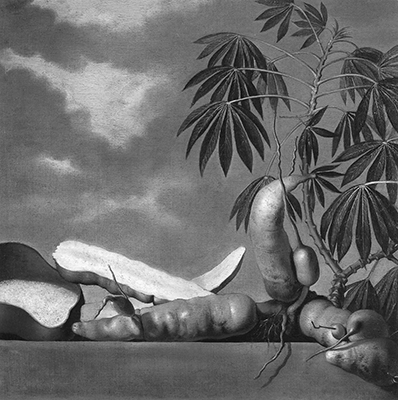

Candied pineapple, dates, and cherries create a colorful still life. The process of candying, or glacéeing, fruit is an old one. It involves steeping cooked fruit in increasingly strong sugar solutions until the sugar permeates the fruit and thereby preserves it. © nutroasters

In fifteenth-century England, according to C. Anne Wilson, “banquetting stuffe”—the sweetmeats, creams, jellies, and other sweet dishes presented for the final service of a feast—included candied fruit and peel, called “wet sucket” when they were stored in syrup and “sucket candy” when dry. See sucket fork and suckets. Early recipes are not always specific as to whether the product is “wet” or “dry,” but it seems likely that until about the seventeenth century, the former was more common. In the sixteenth century Nostradamus indicates that preserves of citrus peel were stored in jars in syrup, whereas candied slices of edible gourd were coated in spiced sugar and stored with sugar in alternate layers. The recipes for candied citrus peel in both Scappi’s Opera (1570) and Bradley’s The Country Housewife and Lady’s Director (1736) are for “wet” variants, though La Varenne, in his Le confiturier françois (1660), expressly states that his candied whole oranges and lemons, orange slices, and orange peel are to be dried on a layer of straw. Massialot, at the end of the seventeenth century, gives instructions “à confire toute sorte de fruits, tant au sec qu’au liquide,” at the same time noting that some fruits, such as berries and grapes, are best preserved in syrup. Nevertheless, even fruit stored in dense syrup could be subsequently extracted from the syrup and dried on slate in a drying oven.

Citrus fruits seem to have been the popular choice for candying, although other fruits could also be used. At the end of the seventeenth century Massialot proposed a month-by-month calendar, starting with green apricots in May and cherries in July, chestnuts in November and December, then oranges and other citrus fruit, often imported, in January and February. Angelica could be harvested for candying in spring, summer, and autumn. See angelica. The range of candidates was broader in the warmer climates of Italy, Provence, Spain, and Portugal. Le cuisinier méridional, published in Avignon in 1839, gives very detailed instructions for candying green apricots, apricot quarters, peaches, plums, figs, pears, quarters of quince, cherries, walnuts, chestnuts, and oranges. The process is very delicate, the author notes, as the fruit has to be at the correct stage of maturity (slightly less than perfectly ripe) and the sugar must be cooked to the right degree. If the syrup is too concentrated, the sugar cannot penetrate the fruit. Furthermore, Indian sugar is preferred to sugar from the West Indies.

Until the nineteenth century, the candying of fruit was mainly a domestic process, often the task of the mistress of the household or, in noble dwellings, the “officier de bouche,” but its production gradually shifted to the domain of the professional, with manuals for professional confectioners becoming more common in the nineteenth century. In France this could well have been a consequence of the Revolution. One of the earliest works outlining the process is Le confiseur moderne, first published in Paris in 1803, the same year that Grimod de la Reynière published the first of his Almanachs des gourmands. Grimod describes in detail the delights of the confiseurs of the rue des Lombards in Paris, with their “confitures sèches et liquides, fruits au candi,” though he makes no explicit reference to “fruits confits.”

Contemporary Production

Candied fruit production today is most often associated with Mediterranean countries, including Portugal, and countries colonized by them. Certain regions have a reputation for the excellent quality of their candied fruits, including Sicily and the town of Apt in southern France. While stone fruit, citrus fruit, figs, and melons are most commonly represented in European manufactures, tropical fruit such as pineapple, papaya, mango, and guava are candied in Mexico, Brazil, and the Philippines. Many Asian countries also use the candying process to preserve fruit; China, where the history of candied fruit dates back to the Sung period (960–1279), produces candied ginger, kumquats, pineapple, and even candied kiwi in slices. In the Moluccas, once known as the Spice Islands, the fruit of the nutmeg—the flesh surrounding the mace-covered nutmeg—is candied and dried.

The commercial process, as practiced at Apt, begins with sorting the fruit to eliminate bruised, imperfect specimens. Next, stones or seeds are removed, and any fruits damaged in this process are discarded. The fruit might then go into a sulfur solution to facilitate the absorption of sugar; this solution can also serve for temporary storage. Any traces of sulfur are removed in the subsequent blanching, followed by several rinses in fresh water. The candying proper starts with immersion in a light sugar syrup that is slowly brought to a boil, followed by cooling in the syrup. This process of immersion, bringing to the boil, and cooling is repeated as many as 15 times, with the concentration of sugar (or sugar plus glucose) in the syrup gradually increased each time until the fruit reaches a sugar content of about 65–70 percent. Because the sugar interacts with hemicelluloses and pectins in the cell walls, candied fruit retains its shape. The fruit is dried on racks, after which it might be glazed to enhance appearance and preserve flavor and texture.

Unsurprisingly, given the labor-intensiveness of the process, candied fruit is a luxury product generally reserved for gift giving and special occasions, typically Christmas in the Western world, New Year in Chinese cultures. In Sicily, the traditional Easter cassata is decorated with candied fruits—cherries, oranges, and, in particular, zuccata, candied squash. This product dates back at least as far as the fourteenth century and was originally made with zucca or edible gourd, an elongated, white-fleshed fruit with pale green skin, the “carabassat” of the Libre de totes maneres de confits. A Sicilian specialty, zuccata today uses squash or yellow pumpkins.

The cost of candied fruit generally restricts their culinary use to garnish or decoration, and few recipes call for candied fruit as a principal ingredient. One of these, variously known as American fruit cake, Brazil nut fruit cake, festive fruit and nut cake, or gourmet fruitcake, is essentially a multicolored mix of candied fruit and nuts held together by a small amount of batter. See fruitcake. Diced candied fruit features in the classic French dessert riz à l’impératrice, while candied citrus peel goes into a variety of cakes and desserts and can also be coated in chocolate.

See also candied flowers; fruit; and mostarda.

candy, strictly speaking, refers to sweets that are made from sugar or acquire their solid texture mainly from sugar, as opposed to pastries, jellies, puddings, and the like. However, the lines are a little vague. Many people would consider gumdrops to be candies, and to Americans, chocolates are candy. In the United States, a box of candy usually means a box of chocolates.

Indian Beginnings

The history of candy begins in India, where sugar was first refined from cane sap. By 100 c.e. śarkarā (“pebbles”) was the Sanskrit word for hard sugar crystals drained from syrup. At this stage, khaṇḍa or khaṇḍaka (“broken piece”) meant a cruder product, soft brown crystalline sugar. These words would travel to Europe by way of Persian (shakar, qand) and Arabic (sukkar, qand). See sugar.

It took centuries for “candy” to come to mean a product made from sugar. The earliest candy was, in effect, śarkarā allowed to develop particularly large crystals. In Arabic it was called sukkar al-nabāt (“plant sugar”) because the crystals “grow” in dense syrup as it cools. This type of large crystal is referred to as rock candy. Although no longer a very important category today, it still appears at the end of a wooden stick for stirring cocktails. And it is still beloved by children, until they discover candies that are not literally rock-hard crystals.

Back in India, the refining process started with a crude syrup made by boiling cane sap so that coarse plant material would rise to the surface, where it could be skimmed off. See sugar refining. This was called phāṇita (in Sanskrit, “skimmed”). In sixth-century Iran, pānīd had surprisingly become the name of the first candy made by dissolving refined sugar and then boiling down the syrup. When the syrup became so thick it was chewy, the syrup would be repeatedly stretched on a peg pounded into a wall to make what is called pulled taffy. See taffy. Boiling the syrup might have started out as a quasi-alchemical attempt to create a super-refined sugar; on the other hand, the taffy-pulling technique might have been known already, because a similar medieval candy was made by boiling down honey. Both kinds of taffy were often kneaded with nuts.

The Arab Period

For the next few centuries, candy innovation moved to the Arab world. The most important discovery of this period was hard candy (called “boiled sweets” in England). See hard candy. This process requires syrup to be boiled to the hard-crack stage, when it is only about 1 percent water. See stages of sugar syrup. If this syrup is cooled quickly, it has no crystalline structure and is technically just a super-cooled liquid, like glass. In fact, molten hard-crack syrup can be worked using the same tools and techniques that a glassblower utilizes.

Like glass, hard candy has a pleasant, smooth texture and is easily broken, so it can be crunched comfortably between the teeth. However, as boiling syrup approaches the hard-crack stage, it may suddenly “seize up” or crystallize. This probably explains a peculiar medieval Arabic name for hard candy, aqrāṣ līmūn, “lemon cakes.” The surviving recipes do not actually call for any lemon juice; they simply instruct the cook to boil syrup until it is about to crystallize, and then to drip it into chilled molds or onto a greased tray.

That might have been enough of a recipe for a professional confectioner, but the term aqrāṣ līmūn suggests cooks had already discovered that adding an acid ingredient such as lemon juice—not necessarily enough to taste but enough to split some of the sucrose molecules into fructose and glucose—interferes with crystallization. (Adding an “invert sugar” such as honey or corn syrup also works for the same reason. One thirteenth-century recipe from Moorish Spain says to add honey so that the syrup “retains its moistness and doesn’t break up.”) The fact that hard candies were called aqrạ̄s līmūn makes one suspect that adding some lemon juice for luck was a nearly universal practice. It is by no means an accident that so many hard candies in modern times have a sweet-sour fruit flavor, like lemon drops and Life Savers. See life savers. And like today’s Life Savers, aqrāṣ līmūn were often colored red, yellow, or green. Brightly colored candy is a medieval heritage.

It is known that these confections had reached Europe by the twelfth century because recipes exist for penidias, hard candy, and even a pulled honey sweet in Mappae Clavicula, a collection of metallurgical and glass-making formulas.

Medieval Arab confectioners also made a sort of pralin or perhaps nougatine (lauzīnaj yābis) by melting sugar crystals in a pan and tossing ground almonds into it; in addition, they created a kind of nougat (al-danaf, nāṭif) by beating egg whites with boiling syrup. See nougat. Finally, they practiced candying, though not with fruits because of the Middle Eastern distaste for fruits’ acidity in sweets. A thirteenth-century Syrian book offers a recipe for candying gourd by treating the pieces with lye and then boiling them in syrup until “if you take a piece into the light of the sun, it looks like amber in translucency and color.” See candied fruit and vegetables and herbs.

Candy Goes West

During the Renaissance, candy innovation moved to Europe. By the fifteenth century, candy-coating was a known practice. Tossing a small item such as a nut in a pan of syrup still makes a host of candies—comfits, Jordan almonds, jelly beans, and m&m’s. See comfit and panning.

European confectioners began to experiment with the use of dairy products in candy. In the late eighteenth century, butterscotch was created by adding butter to sugar syrup, which prevented “seizing up” by making the sugar crystals slide past each other rather than linking up. See butterscotch. This use of fat became so common in the nineteenth century that English confectioners referred to the medieval technique of adding lemon juice as “greasing” the syrup. Around this time dairy products such as milk and cream were added to syrup to make soft, rich candies such as caramels and New Orleans praline. See caramels and praline.

Modern technology has created an endless variety of candies, but such is the human sweet tooth that most of the techniques were already known 800 years ago.

See also corn syrup; fructose; glucose; and honey.

candy bar, an iconic confectionery form consisting of chocolate and other ingredients, is the sweet by-product of two intertwined and indomitable forces: the Industrial Revolution and capitalism. For most of its history, chocolate was prohibitively expensive, mostly consumed in a liquid form and almost exclusively by the aristocracy. But several European innovations of the mid-nineteenth century changed all that. In 1847 the English confectioner Joseph Fry came up with the idea of creating a moldable paste of cocoa powder, sugar, and cacao butter. His discovery was followed by Henri Nestlé’s creation of the first bar of milk chocolate and Rodolphe Lindt’s invention of conching, a process that makes chocolate creamier. See cocoa; lindt, rodolphe; and nestlé. In 1893 American confectioner Milton Hershey saw a conching machine on display and immediately purchased it. Following in the footsteps of Cadbury and other European pioneers, Hershey—considered by Americans the godfather of the candy bar—began to mass-produce and distribute milk chocolate bars in 1905. See cadbury; hershey, milton s.; and hershey’s.

The American market for candy bars was accelerated a decade later by the United States military, which asked Hershey’s and other companies to produce a single-serving portion of chocolate for the ration kits given to soldiers. The doughboys returned home with an appetite for chocolate bars, soon to be called “candy bars,” which quickly spread to the general population. See military.

Ray Broekel, widely considered the world’s leading authority on candy bars, estimates that regional confectioners manufactured tens of thousands of different brands in the “golden age” of candy bars between the World Wars. Most were made of the same suite of ingredients—chocolate, caramel, fudge, and nuts—though locally grown fruits such as cherries, figs, or even pineapple, were sometimes included. The health craze of the 1920s spawned a bar known as the Vegetable Sandwich, consisting of dehydrated vegetables enrobed in chocolate and including the ill-advised tagline “Will Not Constipate.” A decade later, during the Great Depression, candy bars such as the Chicken Dinner and the Club Sandwich—which featured mostly chocolate, nuts, and caramel—sold for a nickel and were advertised as a protean form of fast food, promising the consumer quick energy on the cheap. This emphasis on caloric heft led to the introduction of whipped nougat and marshmallow, which made bars appear larger and therefore more filling. See marshmallows and nougat. All these additions also made the bars cheaper, since the quantity of expensive chocolate was minimized.

Because of the similar ingredients included in most candy bars, manufacturers sought to distinguish their brands through marketing. Some were linked to cultural icons such as Charles Lindbergh, Clara Bow, or Babe Ruth. Other bars celebrated popular expressions (Boo Lah, Dipsy Doodle), exotic locales (Cocoanut Grove, Nob Hill, Fifth Avenue), dance crazes (Tangos, Charleston Chew), local delicacies (Baby Lobster), hit songs (Red Sails), carnival attractions (Sky Ride), even quiz shows (Dr. IQ). During Prohibition, the Marvel Company of Chicago made an Eighteenth Amendment Bar, which boasted “the pre-war flavor” and pictured a bottle of rum on the label. World War II ushered in a battalion of militaristic bars: Flying Fortress, Jeep, Chevron, Buck Private, Big Yank, and Commando.

As documented by Joël Brenner in The Emperors of Chocolate, Milton Hershey and his chief rival, Forrest Mars, quickly came to dominate the U.S. market by automating their factories, establishing a national distribution system, buying out competitors, and stockpiling raw ingredients. See mars. As a result, by the 1980s more than 90 percent of the bars that appeared on domestic candy racks were made by one of three multinational corporations: Hershey’s, Mars, or the European giant Nestlé. (On the world market, Mondelez, which owns Cadbury, is second only to Mars.) Because so much of their equity resides in the production techniques used to manufacture different bars, the confectionery companies are highly secretive. They have been known to blindfold noncompany workers brought in to repair particular machines, and they rarely allow nonemployees inside their plants.