à la mode is a French phrase that translates to “in the current fashion.” In the realm of sweets, it turns out to be even more American than apple pie (whose roots, in fact, lie elsewhere), because in the United States “à la mode” refers to a scoop of vanilla ice cream served with a piping hot slice of pie. See ice cream and pie.

The New York Times credits the spread of this term to Charles Watson Townsend. His 1936 obituary reported that after ordering ice cream with his pie at the Cambridge Hotel, in the village of Cambridge, New York, around 1896, a neighboring diner asked him what this wonder was called. “Pie à la mode,” Townsend replied. When Townsend subsequently requested this dessert at the famous Delmonico’s restaurant in New York City, the staff had no idea what it was. Townsend inquired why such a fashionable venue had never heard of pie à la mode. Bien sûr, the dessert found its way onto Delmonico’s menu and requests for it soon spread.

Not long thereafter several midwestern newspapers provided evidence that John Gieriet of Switzerland had previously invented the dessert in 1885 while proprietor of the Hotel La Perl in Duluth, Minnesota, where he served the ice cream with warm blueberry pie.

The term “à la mode” has become so established in the United States that it now extends to a variety of flavors added to all sorts of desserts. The phrase has also come to be used metaphorically, most recently by the musical group Destiny’s Child that in 2001 recorded a hit song titled “Apple Pie à la Mode,” to refer to a beyond-fabulous lover.

In France, however, à la mode, in a culinary context, refers to a traditional recipe for braised beef, which at one time was considered a new fashion.

addiction, in relation to sweets, refers to the hypothesis that sugar (in certain forms) may be capable of triggering an addictive-like process in vulnerable individuals. Changes in the food environment and the manner in which sugar is incorporated into food may be related to neurobiological and behavioral changes in our eating that resemble addiction. If sugar can be addictive, this may speak to why our relationship with food is so difficult to change, and why sugary products are a major contributor to the obesity epidemic.

The food environment that we live in has changed dramatically over the last 30 years. Ultra-processed, highly palatable foods are cheap, easily accessible, and heavily marketed. The addition of higher levels of sugar has been one of the major drivers of this change, along with increased levels of fat, salt, refined flours, and food additives. Hyper-palatable foods (like ice cream, cakes, and candy) surpass the level of reward associated with more natural, minimally processed foods such as vegetables, fruits, and nuts. The rising rates of obesity and binge eating that have accompanied the influx of these types of foods have led to the hypothesis that hyper-palatable foods may be capable of triggering an addictive process.

Sugar is not inherently addictive. In fact, sugar (along with fat and salt) is important for our survival. The high-calorie content associated with sugar and fat ensures that we do not starve in times of food scarcity, and sodium derived from salt is essential for a number of important bodily functions (e.g., fluid balance, nerve function). Humans may even have evolved a greater reward response to these life-sustaining nutrients to ensure that we were motivated to seek out and consume them. See sweets in human evolution.

Nevertheless, the way sugar exists in our current food environment is significantly different from the naturally occurring foods our brains may have evolved to expect. In fact, many high-sugar foods have been altered in a manner analogous to the way in which drugs of abuse are created. Both the elevated potency of a substance and its rapid absorption into the bloodstream increase its addictive potential. Many drugs of abuse derive from plant materials that are refined into highly concentrated substances (e.g., grapes into wine) to become more potent, and to allow the active ingredient to be more quickly absorbed into the bloodstream. For example, when the coca leaf is chewed or brewed as tea, it produces only mild stimulation and is thought to have little addictive potential. Yet, when the leaves are refined into a powder form, such as cocaine, they become a very potent, quickly absorbed, and highly addictive substance. An analogous process has occurred with many high-sugar foods.

In many of the processed foods available today, sugar comes in higher doses and is coupled with other rewarding ingredients (e.g., salt, fat). For instance, one of the greatest sources of naturally occurring sugar is fruit. See fruit. A banana (a relatively high-sugar fruit) has approximately 16 grams of sugar. In contrast, modern candy bars can have up to 40 grams of sugar—over double the dose of sugar in the banana. Moreover, many candy bars combine sugar with high levels of fat, whereas most fruits have little to no fat. See candy bar. In fact, very few naturally occurring foods contain high levels of both sugar and fat (e.g., avocados and nuts have fat, but little sugar). Furthermore, many of these ultra-processed foods have been stripped of fiber, water, protein, and other components that would slow absorption of ingredients like sugar into the system, so their consumption leads to a bigger blood sugar spike and likely increases the brain’s reward response. Thus, in comparison with the food environment humans evolved in, our foodscape is composed largely of foods with unnaturally high levels of rewarding ingredients that are combined to increase palatability, to have a greater impact on the body.

Sugar-Addicted Rats

Much of the initial research on food and addiction emerged from animal models of eating behavior. Rats given intermittent access to sugar (in addition to standard rat chow) binge on progressively larger quantities of sugar, exhibit signs of withdrawal when sugar is removed, and display greater motivation for traditionally addictive substances (e.g., alcohol). Animals consuming sweets (like Oreos and cheesecake) are more likely to binge on these foods when stressed and will continue to seek out these sugary foods despite receiving electric shocks. Not only do these animals exhibit extreme behaviors, but also their consumption of these highly palatable foods is related to changes in their brains that have been linked with addiction, such as a reduction in dopamine receptors.

Sugar Addiction in Humans

Neuroimaging and behavioral research in humans also provide evidence of the addictive potential of sweet foods. Palatable foods (including high-sugar foods) and drugs of abuse activate similar brain systems (e.g., dopamine and opioid systems). Obese and substance-dependent participants exhibit similar patterns of neural response to cues (i.e., increased activation in motivation and reward areas) and consumption (i.e., decreased activation in control and reward areas) of palatable foods and drugs, respectively. Furthermore, healthy-weight individuals who consume ice cream more frequently display in the fMRI scanner a lower reward-related response in the brain when consuming a milkshake. This may reflect the development of tolerance to the hedonic effects of ice cream analogous to the way that people develop tolerance to the rewarding effects of drugs of abuse.

The Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS) was developed to measure addictive-like eating in humans by translating the diagnostic criteria for substance dependence (e.g., withdrawal, loss of control) to evaluate food consumption. Sugary foods, such as chocolate, are often identified as problem foods on the YFAS. The prevalence of YFAS food addiction may be around 5.4 percent in the general population; addictive-like eating is associated with severe obesity and a higher percentage of body fat. Individuals exhibiting more symptoms of food addiction on the YFAS (regardless of body mass index [BMI]) showed a pattern of neural activation in response to cues and consumption that is implicated in other types of addiction; they also have genetic indicators associated with elevated risk for addiction. The similarities identified in the neural system converge with behavioral overlap between addiction and problematic eating. For example, diminished control over consumption, continued use despite negative consequences, elevated levels of craving, and repeated relapse to problematic behavior are key constructs for both problematic substance use and eating behavior.

If sugar is addictive, it would not affect adults alone. Children naturally prefer high levels of sugar and are motivated to eat sweet things (like sugar-sweetened cereals). Children are also more vulnerable to the negative effects of addictive substances, because their brains and psychological coping strategies are developing. Research in this area is just beginning, but children who report more food addiction symptoms on the YFAS have higher BMIs and are more likely to overeat due to emotions. Thus, addictive-like eating may start in childhood for some individuals, which could contribute to lifelong eating-related problems.

Sugar Addiction and Public Health

In summary, the research suggests that for certain people sweets (and other ultra-processed foods) may be capable of triggering an addictive process that results in compulsive food consumption. Yet, there are still more questions than answers in this burgeoning line of research. For instance, there have been almost no studies examining what might be the active ingredient in foods that would make them more addictive, although high levels of sugar are a likely possibility. Identifying which foods may be addictive is especially important when we consider the huge public health costs incurred by addictive substances. Although a significant proportion of people develop full-blown addictions, the number of people who develop “subclinical” problems with addictive substances is far greater. Take the example of alcohol. Around 5 to 10 percent of people develop an addiction to alcohol, but it is the third leading cause of preventable death in the United States. This statistic is driven in large part by individuals who exhibit enough of a subclinical addictive response to alcohol (e.g., binge drinking) that they overconsume it in a way that threatens their health and safety.

Like alcohol, addictive foods may have a huge public health cost that will be driven in large part by the group of adults and children who exhibit a subclinical response. This may be especially true in the case of hyper-palatable, high-calorie foods, as only a few extra hundred calories a day can lead to obesity. Thus, if someone is showing a subclinical-addictive response to these foods, such as struggling to control their level of consumption, that person could face elevated food intake and increased weight gain. Given that highly processed foods are cheap, legal, and more accessible than alcohol and tobacco, the public health costs associated with potentially addictive foods could be significant.

Greater understanding of addiction should suggest possible avenues to reduce negative consequences. Encouraging people to make behavioral changes and providing treatment for individuals with addictions are important, but it is also necessary to focus beyond personal responsibility or clinical disorders to reduce the public health costs of addictive substances. In the case of cigarettes, public policy has been an important tool. Specifically, policies focusing on changing the availability, marketing, and costs of tobacco products have resulted in huge public health gains. Similar environmental interventions may be needed to reduce the consequences of potentially addictive ingredients like sugar.

See also soda and sugar and health.

adulteration is the process by which foods are debased with extraneous, weaker, cheaper, harmful, or inferior ingredients. In terms of sweeteners, honey, fruit juice, jams, and agave nectar have been adulterated with cheaper additives made from cane sugar, beet sugar, rice, corn syrup (including high-fructose corn syrup), and other ingredients. Producers of “maple syrup” have added less expensive sweeteners or injected air into the syrup to increase bulk.

Most added sugars are not usually harmful to health. National and regional food agencies have developed tests to determine whether natural sweeteners have been adulterated with other products, but government agencies cannot test every product and often only do so when a complaint has been lodged.

There are less common cases, however, in which antibiotics, heavy metals, and other harmful impurities have ended up in natural sweeteners. This adulteration has been associated with honey imported from Asia, particularly China. Honey imported from these sources has been banned in Europe. In the United States, it is common to filter out the pollen from the honey in food processors. Often processors also infuse honey with hot water, which thins the honey, adds bulk, and makes it easier to process and less difficult for customers to remove from containers. Such tampering is neither illegal nor unsafe, but critics claim that honey without pollen or with added water is not natural honey. Filtering out pollen removes impurities, extends honey’s shelf life, and makes for a more consistent liquid product, which appeals to American consumers who generally dislike honey crystallization.

Critics have called for changes in the definition of processed sweeteners. They have also called for improved labeling that indicates whether natural sugars are processed or in their raw form, whether sugars and water have been added, and whether natural ingredients have been filtered out.

See also honey.

advertising, American is older than the United States itself; European colonists had brought the idea of advertising with them to the New World. In the early American colonies, most advertising was local and resembled current-day classified ads. In 1705 the first known ad for the chocolate trade appeared in the Boston Newsletter, offering cocoa, chocolate, and molasses among other commodities for sale. Twenty-five years later, the New York Gazette carried the first ad for an American sugar factory selling all sorts of “sugar and sugar candy.”

By the mid-1800s machines were mass-producing goods with uniform quality, and large companies had increased production. For the first time, it cost people less to buy a product than to make it themselves. In the Victorian era, factories also started to manufacture sweets, including individual hard candies, chocolate bars, the modern marshmallow, chewing gum, and toffee.

Post–Civil War to 1920s

Between 1870 and 1900 the price of sugar dropped, causing the commodity to lose its luxury status. Jam became an important product for the working class, and dessert gradually became standard as a sweet course after dinner. As more mass-produced consumer products became available, manufacturers looked for ways to tell people about them.

Brand Name Advantage

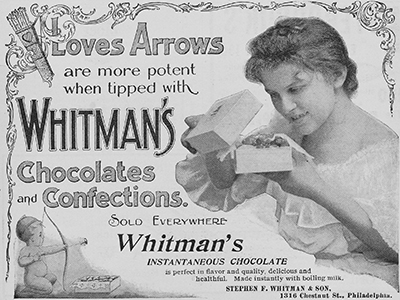

The key to a product’s success lay in the national advertising of a memorable brand name, attractive packaging, and a trademark that could differentiate one product from others on the market. For example, printed labels on pottery jars enhanced the appeal of Keiller’s Dundee marmalades, whereas a collection of “Choice Mixed Sugar Plums” from Stephen F. Whitman became the first packaged confection in a trademarked box. See chocolates, boxed. A change in packaging could also reposition a product. While other grocers were filling cheap containers, P. J. Towle filled a miniature, log-cabin-shaped tin with his blended table syrup. Customers willingly paid extra for the novelty.

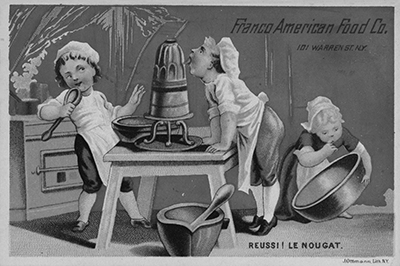

The Franco-American Food Company, founded in 1887 by the French immigrant Alphonse Biardot, skillfully adopted early advertising practices to build its brands, which initially included sweet products. This late-nineteenth-century chromolithograph is from a set of advertising trade cards. private collection © look and learn / barbara loe collection / bridgeman images

Sales also soared for Cracker Jack, mostly due to the advertising of an appealing package. Street-food vendors Frederick and Louis Rueckheim first sold the new confection of popcorn, molasses, and peanuts at amusement parks. In 1896 they registered the name Cracker Jack, common slang for “first rate.” They then packaged their snack in a wax-sealed box, which kept it fresh for a long time, and marketed it to professional vendors at baseball parks. The slogan “The More You Eat, the More You Want” summed the product’s appeal. See cracker jack.

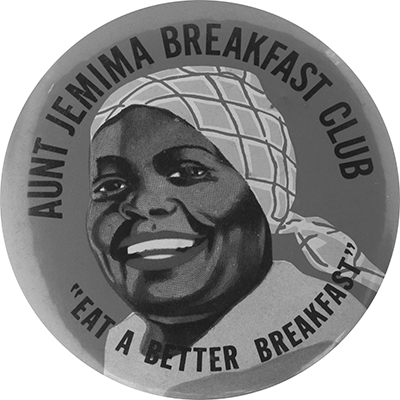

As companies moved from a production to sales orientation, they packaged and branded their products, and engaged in heavy national advertising. Among the early brands of this era, the image of the smiling Aunt Jemima first appeared on boxes of a self-rising pancake mix in the 1890s. The Davis Milling Company hired Nancy Greene, a black cook, to serve as a living trademark for the product. In this persona she traveled around the country and cooked thousands of pancakes at fairs, inspiring the ad line “I’s in Town, Honey.” See aunt jemima.

National Advertising Campaigns

By 1900 the majority of the revenue for newspapers came from advertising, and national brands appeared in regional and local papers. National magazines also became part of everyday life. Advertisers gradually began to turn their campaigns over to advertising agencies to be integrated into sound marketing strategies.

The National Biscuit Company (later Nabisco) set the standard for the well-coordinated advertising plan with the introduction of Uneeda Biscuit, a flaky soda cracker. With a brand name chosen, it created an airtight, wax-lined package that looked different from anything else but would ship well. Next it conceived a distinct image and then spent an unprecedented amount on advertising. This trademark identity theory essentially passed through Nabisco’s whole product line of cookies, including Fig Newtons, Oreos, and Animal Crackers. See animal crackers; fig newtons; and oreos.

Early brands of this era included Jell-O gelatin, Domino sugar, and Wrigley’s spearmint gum. See chewing gum; gelatin deserts; and american sugar refining company. The manufacturers of Jell-O embarked on a massive advertising campaign, calling the unheard-of packaged good “America’s Most Favorite Dessert.” They also reached the public with recipe booklets and promotional items, and hired artists like Norman Rockwell and Maxfield Parrish to contribute illustrations for lavish ads. Similarly, the American Sugar Refining Company began labeling the company’s sugar products “Domino” after the sugar cube, to convince grocers to purchase its product in packages rather than in bulk.

Entirely new products like Crisco also joined the list of nationally advertised brands. When Procter & Gamble began processing its own oil, a key ingredient in soaps, the company also began to develop a vegetable shortening that would remain solid year round. One of the first Crisco ads appeared in the 1912 Ladies Home Journal, announcing “An absolutely new product. A scientific discovery that will affect every kitchen in America.” In addition to national advertising, P&G also sponsored cooking schools to promote its product’s benefits over animal fats. See shortening.

1920 to World War II

For the first time, more than half of the nation lived in urban areas, providing marketers with a ready-made mass market. Whatever they had to sell, most advertisers aimed their message at the American woman. For decades, statisticians estimated that women accounted for 80 percent of all household purchases.

Betty Crocker

By the 1920s there were well-developed advertising vehicles to reach the women’s market. When General Mills ran an ad in national magazines with a puzzle for its Gold Medal brand flour in 1921, the contest generated thousands of responses, many of which included questions on food preparation. Since the company could not personally respond to every letter, it decided to send recipes collected from its employees and sign them with the friendly but fictitious name of Betty Crocker. Betty Crocker served as a valuable persona. Actresses representing her ran regional cooking schools and, beginning in 1924, regional radio programs. See betty crocker.

One of the early products that came under the Betty Crocker brand was Bisquick. In 1931 the package appeared with the slogan, “Makes Everyone a Perfect Biscuit Maker.” While Betty’s name continued to be used, her picture did not appear in print ads until 1936. Despite the promises of convenience, biscuit, cake, pie crust, and muffin mixes were not associated with good eating until the 1950s.

Craze for Sweets

Sugar demand and consumption exploded in the 1920s and 1930s. The postwar crash in sugar prices allowed candy makers to sell chocolate bars at lower prices, and solid chocolate surpassed drinking chocolate in popularity. But the familiar wrapped candy bars did not appear widely until merchants put them adjacent to cash registers in grocery stores, drugstores, newsstands, and cigar stores. See candy bar.

The arrival of modern refrigeration led to affordable frozen novelties. In 1919 Christian Nelson, an ice cream parlor owner, found a way to dip blocks of frozen ice cream in chocolate. He called them “Temptation I-Scream Bars.” They were so popular that, with entrepreneur Russell Stover, he began to mass-produce them, wrapping each one in aluminum foil and changing the name to Eskimo Pie. However, Good Humor is credited as the first company to put ice cream on a stick, with the slogan “The New Clean Convenient Way to Eat Ice Cream.” See eskimo pie and good humor man.

Americans also enjoyed frozen ice on a stick in fruit flavors that had the same appeal as soft drinks. In 1923 Frank Epperson introduced frozen pop on a stick at amusement parks and beaches. See popsicle. The first ads for the product, which sold for a nickel, explained what it was by calling the popsicle (initially named “the Epsicle ice pop”) “the Frozen Drink on a Stick.” At the height of the Depression, when the company was looking for ways to make the treat more affordable, it produced a splittable popsicle with two sticks so that children could share it.

Small, packaged desserts also became popular with both children and adults. In 1914 the Tasty Baking Company produced individually wrapped snack cakes with the catchy name Tastykake. Baked and delivered fresh daily, each boxed mini-cake sold for a dime. Five years later, Continental Baking introduced its first snack cake—a devil’s food frosted cupcake. Persuasive advertising contributed to the success of this new product line, called Hostess: “Now baking cake at home is needless … these famous cakes will eliminate all that drudgery.” See hostess.

After the Wall Street crash of 1929, the economy hit hard times. So did advertising. But radio surged ahead to become the nation’s first free entertainment medium, and advertisers could quickly reach a national audience. During this time Jell-O sponsored the Jack Benny Comedy-Variety Hour. The comic skillfully mentioned the sponsor’s name in the script both at the start and the end of the program (“Jell-O again. This is Jack Benny”).

While daytime soap operas were largely aimed at housewives, the roster of shows extended to adventure series and westerns targeted at children. The malted chocolate drink mix Ovaltine sponsored one of the most well-known of these programs, Little Orphan Annie. By redeeming box tops and a small amount of cash for “postage and handling,” young fans could receive such premiums as a whistling ring, mug, or secret decoder that could decipher the daily clues given at the end of the broadcast.

To improve its effectiveness, the National Confectioners Association decided not only to advertise its member companies’ products but also to market the industry as a whole. It commissioned a study to assess the amount of money the candy industry spent on advertising compared to the amount other groups spent on promoting their respective products. After discovering that candy was “the least advertised food product,” the confectioners launched the “Candy Is Delicious Food—Eat Some Every Day” campaign in 1938. A series of ads touted the message “Candy Is an Energizing Food” as part of the “Candy as a Wholesome Food” campaign.

When chocolate was promoted as nutritious, World War II soldiers found Hershey bars, Mars candy-coated chocolates, and Tootsie Rolls in their survival rations. See military. To support the war effort, the Kellogg Company also supplied packaged products. In 1941 it added the Rice Krispies Treats recipe to the back of the Rice Krispies cereal box and trademarked the simple dessert. This crispy yet gooey snack became a popular item to mail to soldiers serving overseas. However, since the consumption of butter, sugar, and chocolate among other staples was limited on the home front during the war years, few other new snacks were introduced until later in the decade.

1950 to 1990

The postwar economy recovered quickly. As more and more imitative products showed up in the marketplace, advertising’s emphasis shifted from product features to brand image to align brands with the most profitable market segments based on class, race, gender, and age. The emerging marketing concepts placed even more emphasis on research.

Elaboration of Target Markets

Where goods for the home were concerned, women represented a crucial market for frozen foods, precooked meals, and dry mixes. In 1947 Pillsbury hired the Leo Burnett Company to launch a new line of ready-to-use cake mixes aimed at this group. See cake mix. The ads repeated a simple message: just drop this mix in a bowl, add water, mix, and bake. But sales were slow. Motivational research revealed that the problem lay in the powdered eggs used in the mixes. So the manufacturers changed the package directions: “You add fresh eggs” or “You add fresh eggs and milk,” allowing women to feel more involved in baking, and the sale of cake mixes took off.

The ultimate in convenience came with Sara Lee’s cakes, which perfected a process in which cakes could be baked, frozen, and then shipped, a first in the food industry. In 1951 Sara Lee’s marketing strategy focused on the taste and quality of its ingredients, such as the number of pecans in its All Butter Pecan Coffee Cake. Later the emphasis shifted from product features to emphasis on the product as an everyday treat, using the memorable line “Nobody Doesn’t Like Sara Lee.” See sara lee.

Children also represented an enormous demographic to food manufacturers, and the new medium of television provided a way to quickly reach a national audience. Howdy Doody, Miss Frances of Ding Dong School, and Captain Midnight all sold Ovaltine. The producers carefully worked the product into songs and ads. As the 1960s unfolded, advertising to children and youth began in earnest. In 1962 McDonald’s introduced advertising campaigns with cartoonlike characters to appeal to children. By 1970 the bulk of advertising on children’s TV programs pitched sugared foods. Among them, Nestlé Quik introduced the animated cartoon bunny wearing a “Q” on his shirt for its flavored milk mix. The bunny reminded young viewers: “It’s so rich and thick and choco-lick! But you can’t drink it slow if it’s Quik!”

The large volume of television advertising directed at children elicited concern from many parents, consumers, and legislators. As a result, the Children’s Advertising Review Unit (CAU) was founded in 1974. The self-regulatory organization set high standards for the industry to assure that national advertising directed at the child audience was not deceptive, unfair, or inappropriate. When CARU found violations, it sought changes through voluntary cooperation.

By 1970 greater emphasis on the consumer began to take place, as the idea of market segmentation took hold in most companies. Recognizing social trends and increased income potential, advertisers began to segment and target more specific groups. They also tied their products to distinct lifestyles, immediate gratification, youth, and sexuality.

Yuppies—young urban professionals—were one of the earliest lifestyle target groups to receive attention. In the 1980s they exhibited an unlimited appetite for consuming premium goods. Häagen-Dazs offered luxury ice cream, making it exclusive, sophisticated, even sexy. Godiva chocolate ads presented classic images of prestige, luxury, and refinement. Pepsi then showed what money could buy, trotting out a list of celebrities from Michael Jackson to Madonna to get their message across: Pepsi was “The Choice of a New Generation.” See godiva and häagen-dazs.

The New World for Advertising

As the 1990s unfolded, the internet had a dramatic effect on the advertising industry. Within a very short time, new media options based on new technologies reinvented the very process of advertising. Sales messages once clearly labeled were now subtly woven into movies and TV shows, or made into their own entertainment. Other promotions involved play, like video games with brand messages embedded in colorful, fun adventures. Meanwhile, the M&M characters went “virtual Hollywood” across the internet. See m&m’s.

Within a very short time, computer technology had a huge impact. Advertising is no longer just advertising; it now involves consumers by soliciting their experiences and engaging them in conversation. An excellent example is one of the most talked about viral videos, the sublime “Cadbury Gorilla” playing the drums to a Phil Collins hit. Released in 2007, it has since been enjoyed by millions. There is no talk of chocolate at all; rather, the 90-second spot aims to make people smile, subliminally suggesting the same pleasure provided by a bar of Cadbury Dairy Milk Chocolate.

American advertising has come a long way since its first simple announcement for sugar candy. Sweets are now sold as an undeniable pleasure. They are fantastic, fun, and a sign of love. Over the years sweets have been promoted as a sinful indulgence while simultaneously being marketed as wholesome energy-dense snacks, at times even to help you keep slim. Through such associations, ads for sweets offer a connection with the product and a promise of guiltless pleasure.

See also cadbury; candy; children’s candy; confection; ice cream; nestlé; race; sugarplums; twinkie; and united states.

agave nectar (or syrup) is a sweetener made from agaves. The agaves are a genus of succulent plants, native to the Americas, with most species concentrated in Mexico. In the United States they are best known as ornamental garden plants and the source of tequila, which is made by expressing the liquid from the cooked core, piña, of Agave tequilana, fermenting the solution, and distilling it.

Patents for commercial production of agave sweeteners date from the 1980s. In the mid-1990s entrepreneurs began marketing agave nectar as an ancient, natural, raw health food, high in fructose and with a low glycemic index. Consumers seeking a less refined, less glucose-dense sweetener than cane or beet sugar, particularly those who adhered to a “Paleolithic” diet, enthusiastically adopted the syrup. Agave syrup’s aura declined as scientists and physicians argued that it is neither ancient nor significantly different from other calorific sweeteners in its chemical and dietary properties. See sugar and health. Various brands of agave nectar continue to be widely available in health food stores and supermarkets.

The traditional Mesoamerican way of extracting sweet liquid from agaves involves cutting an opening in the core of the mature plant. Using a long hollow tube, collectors could daily suck out 3 to 6 liters of sweetish sap, gathering 500 to 1,000 liters from each plant. After some processing, the sap is either drunk as aguamiel (“honey water”), widely and correctly believed to be nourishing and healthful, or fermented into pulque, the traditional mildly alcoholic drink of Mexico. By contrast, commercial production appears to involve chopping and centrifuging the starchy core of the plant, something not always obvious from labeling and promotional material. The resulting liquid is treated with chemicals to create the agave nectar.

See also fructose; glucose; and mexico.

akutuq is known by outsiders as Eskimo ice cream. Pronounced auk-goo-duck, the word “akutuq” means “to stir.” This indigenous dish (1 part hard fat, 1 part polyunsaturated oil, and 4 parts protein or plant material) has been the culinary lifeblood of Natives in North America’s Arctic for 600 generations, nourishing families and traveling hunters. In its savory form, akutuq is considered analogous to the Indian pemmican bar. In its sweet berry-filled form, akutuq remains a favorite dessert.

Although precise ingredients may differ, Inupiaq elders still adhere to a basic method of preparation. Traditionally, the best hard white caribou fat (from the area surrounding the small intestines) is softened and whipped until fluffy. Then seal oil, rendered until clear and golden, is slowly beaten into the mass. After 45 minutes of beating with splayed fingers, tablespoons of water are whisked in, lightening it further and making it fluffy. In appearance and texture aqutuq resembles a classic French buttercream stabilized with sugar syrup. But after icy flavoring ingredients from the permafrost cellar or freezer are added, the silky-smooth consistency “breaks.” The mass instantly loses volume, appearing curdled. No one minds. It is a classic texture and has always looked that way.

Classic flavorings include salmonberries and blueberries, which are folded into the whipped mass. The labor-intensive dish used to be kept in permafrost cold cellars, ready for impromptu get-togethers. Until the early 1900s, yearly trade fairs featured raucous akutuq cooking contests, with husbands cheering wives on to create new flavors with fermented fish eggs or seal flippers—the more outrageous, the better. Today, southern Native Alaskans prepare akutuq by whipping Crisco shortening with sugar in lieu of the original, indigenous ingredients that are low in saturated fat. Schoolteachers (whether Native or not) do the same, to the detriment of a healthy Native lifestyle and the culinary traditions of the Inupiaq.

Alkermes, confection of, is a sweet medicinal syrup of Arab origin, a cordial made with kermes or cochineal, two bitter red dyes derived from insects. The first recorded recipe, written by the Persian physician Yūhannā Ibn Māsawaih (777–857 c.e.), calls for kermes-dyed silk, apple juice, rosewater, sugar, gold leaf, cinnamon, ambergris, musk, white pearls, aloes, and lapis lazuli. This expensive concoction was prescribed to strengthen the heart and to cure melancholy and madness. Translators and practitioners brought the recipe to medieval Europe, where “confectio alchermes” became a valued remedy. During the Renaissance, variations on the confection appeared in many European medical treatises and handbooks, with spices replacing some of the more expensive original ingredients. By the early 1600s the defining ingredient of the confection, kermes (Kermes vermilio), had been largely supplanted by cochineal (Dactylopius coccus), a more intense red dye produced by a Mexican insect. Despite alterations, the confection’s reputation continued to grow, and it was prescribed not only for weak hearts and depression but also for plague, poisoning, and childbirth. Casanova used it as an ingredient in sugared comfits that also contained his paramour’s ground-up hair, and when made up in “Aromaticum Lozenges,” the confection was said to sweeten the breath. Often the confection was combined with alcohol before it was administered. This development reached its zenith in Florence in 1743, when the Dominican monks of Santa Maria Novella created an Alkermes liqueur. In the 1800s physicians increasingly questioned the efficacy of the confection, and it disappeared from the pharmacopeia, although Alkermes is still sold as a liqueur.

ambergris is a waxy calculus that is created in the digestive tracts of sperm whales in response to irritation caused by the sharp, indigestible beaks of ingested squid. It is usually found washed up on beaches or floating in the ocean. It turns up all over the world, but it is most commonly encountered on the coasts of the Indian Ocean, Australia, and New Zealand. This enormously variable substance occurs in irregular or round lumps ranging in weight from a few grams to many kilos. A piece weighing 336 pounds was sold in London in 1913. Ambergris is a brown, black, gray, or white grainy substance and has a faint odor that ranges from mildly fecal when relatively fresh, to “musky” or “earthy” when mature. It is thought to improve from spending a good deal of time in the ocean, but the quality of its scent varies from sample to sample. That of gray ambergris is said to be the best.

Ambergris was an important flavoring in high-status renaissance and baroque confectionery and cookery. It was frequently used in the production of dragées and biscuits, often in combination with musk. To perfume these items, most professional confectioners used a tincture or essence of ambergris, which was made by macerating the ambergris in alcohol in a closed vessel exposed to the heat of the sun or in a stopped glass immersed in hot dung. Lady Anne Fanshawe (1625–1680) included ambergris in combination with rosewater in a circa 1664 ice cream recipe. Sir Edward Viscount Conway (1564–1630), Principal Secretary of State to Charles I, gave his name to a sweet ambergris pudding, recipes for which were published in a number of seventeenth-century cookery texts.

ambrosia is “the food of the Gods” in Greek mythology, but in the earthly realm it is a cross between a salad and a dessert. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the word “ambrosia” referred to a drink; the Oxford English Dictionary describes it as “a mixture of water, oil, and various fruits anciently used as a libation; also a perfumed draught or flavored beverage.” It is uncertain exactly when the leap from cup to plate occurred, but published American recipes for ambrosia date to the late 1800s. The earliest, such as the one in Woods Wilcox’s Buckeye Cookery (1877), call for sprinkling sugar between layers of peeled, sliced oranges and grated “cocoanut.” By the early twentieth century cut-up pineapple found its way into the recipe. Mid-twentieth-century versions included whipped cream, marshmallows, bananas, nuts, and raisins.

The growing popularity of ambrosia throughout the United States followed the widespread distribution of citrus fruits from Florida. Ambrosia took hold especially in the American South, most likely due to the South’s fondness for sweets. Sparkling cut-glass bowls adorn groaning sideboards during the winter holiday season, when serving ambrosia is traditional, and family feuds are fought over dried versus freshly grated coconut. Although ambrosia is classified under “salads” in most Southern cookbooks, it can be eaten after the meal as well as along with it.

American Sugar Refining Company is the world’s largest refined cane-sugar producer and the maker of Domino Sugar, among other major brands. Trademarked in 1906, the name Domino was derived from the fact that the rectangular shape of the company’s sugar cubes resembles the pieces used in the namesake game.

The company traces its roots to the so-called Sugar Trust, known as the Sugar Refineries’ Company when “Sugar King” Henry Osborne Havemeyer organized it in New York in 1887. See havemeyer, henry osborne and sugar trust. Modeled on the nation’s first trust, John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, this then-new form of industrial entity was created by a merger of many separate refineries in several eastern seaboard cities. A near-perfect monopoly, fully legal at inception, it was designed to fix prices, limit supply, keep down labor costs, and discourage competition.

In 1890, however, the company was confounded by passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act. Havemeyer was not deterred. After a New York State court forced the company’s dissolution, he simply tweaked its name, reorganized it as a holding company, and chartered the American Sugar Refining Company—the American, for short—in New Jersey. “From being illegal as we were, we are now legal as we are: change enough, isn’t it?” Havemeyer remarked.

Havemeyers & Elder was the company’s flagship—a half-dozen massive structures situated on a quarter-mile parcel along the Brooklyn waterfront. Almost completely destroyed by an 1882 fire, the site was rebuilt two years later to become the largest sugar refinery on the planet. In 1905 the company was selling about 1.5 billion pounds of sugar a year. Havemeyer once remarked that he had the capacity to supply the sugar demand of the entire country, plus 20 percent.

As the company forged linkages between its refineries and banks, retailers, coal companies, railroads, and the like, legal tangles and government scrutinies were never far behind. In 1911 a special committee of the U.S. House of Representatives began a major investigation. A prolonged affair interrupted by World War I, it was finally concluded with a 1922 decision stating that although the firm had once violated antitrust laws, it was no longer doing so.

The judgment was fair enough, not because the company’s philosophy or tactics had changed but because the sugar business itself had. Factors such as increasing competition from high-fructose corn syrup and other sweeteners, artificial and otherwise, were diminishing the company’s share of the market. See artificial sweeteners and corn syrup. Also, the leaders who took over after Havemeyer’s death in 1907—Havemeyer’s son Horace being among them—intensified the company’s focus on its already existing interests in Caribbean sugar plantations, where it was more difficult for the U.S. government to intervene.

The 1920s brought the so-called Dance of the Millions to Cuba, when that country’s sugar prices soared, due to World War I’s destruction of the beet industry in Europe. The American profited, until the crash. What hurt the American even more badly than the Great Depression was World War II. First came disruption of unrefined sugar deliveries from the Caribbean and Central America, then the double whammy: sugar rationing. See sugar rationing.

A slow decline in the industry occurred over the next several decades as high-fructose corn syrup rose to the ascendancy and health advocates condemned refined white sugar as nothing less than “White Death.” See sugar and health. In 1970 the American became the Amstar Corporation, the name change reflecting a growth in its activities beyond sugar refining. In 1984, still struggling, the company was bought at a bargain price by the private investment banking firm of Kohlberg, Kravis, Roberts & Company and, after almost 100 years, ceased to be publicly traded. (The American had been among the original 12 Dow Jones stocks to be traded when the index debuted on 26 May 1896.) Merrill Lynch owned Amstar for one year (1986–1987). The following year the large English sugar company Tate & Lyle acquired Amstar’s American Sugar Division. See tate & lyle. Tate & Lyle renamed it the Domino Sugar Corporation in 1991.

In 2001 the company was sold to the Florida Crystals Corporation, headed by Alfonso “Alfy” and José Pepe Fanjul Sr., whose family founded vast sugarcane plantations and sugar mills in Cuba in the nineteenth century—all of it lost when Castro assumed power in 1959. See plantations, sugar and sugar barons. Their former mansion in Havana is now a museum. After immigrating to the United States, the Fanjuls began anew, establishing plantations and mills in the Florida Everglades, Dominican Republic, and elsewhere. In recent years, the Fanjuls have been excoriated in the media for their labor practices, treatment of the environment, ties to politicians from both parties, and a gilded lifestyle that rivals Havemeyer’s. But what the Sugar King wrought can no longer be ascribed to any individual’s might. Big Sugar is what this bittersweet empire is aptly called today. See sugar lobbies.

See also fructose; sugar cubes; sugar refineries; sugar refining; and sugarcane.

See chemical leaveners.

ancient world is a general term for the classical Greek and Roman civilizations that flourished in southern Europe from about the seventh century b.c.e. to the fifth century c.e. Greeks developed a high culture in gastronomy, as they did in many other aspects of life. Romans, imitating and at the same time despising the Greeks, transformed this culture and spread it, along with their empire, from end to end of the Mediterranean.

For Greeks and Romans, “sweet” was merely one taste quality among many. To dieticians in particular, who based their prescriptions on humoral theory, sweet substances and ingredients were in general classed as “hot” and were to be taken sparingly or avoided by those with hot constitutions. Since alcoholic drinks were also hot, as were most spices, honeyed and spiced wines were extremely hot and were taken before the meal: their heating effect would be mitigated by the “cold” foods to be served later. See medicinal uses of sugar.

If sweets are now almost defined by their inclusion of sugar, sugar as we know it had no part in ancient dining. The Greeks and Romans knew of cane sugar, a rare spice imported from distant India by way of Alexandria, but it was so expensive that it was used only as a medicine: sugar is not called for in any surviving food recipe from the ancient world. Instead of sugar, the sweets of the ancient world were sweetened with dried fruits, or grape syrup, or honey. See honey and pekmez.

Sweets came last in ancient Greek and Roman meals, as they do in modern Europe. They formed a separate, smaller course and were prepared by specialized pastry cooks; hence, there is no section on sweets in the Roman cookbook Apicius. Yet these were the flavors that lingered in the mouth when the earlier course had already slipped from the diner’s memory. In ancient dining the frontier between “first tables” and “second tables” was, as the very names suggest, an almost physical thing. Tables being small and portable, the first tables, smeared with the remains of the meat and fish dishes, the beans, and soups and stews, were taken away to be replaced by the second, laden with sweet foods. Music and dancing intervened to make the break even clearer.

Greek and Roman writings, when they describe dinner at all, are sadly unspecific about second tables. We fall back on a few rare, specialized sources that supply names and (in rare cases) brief recipes for cakes and sweets. Unexpectedly useful is the earliest of all Latin prose texts, Cato the Elder’s short work On Farming from about 150 b.c.e., which includes a dozen recipes for cakes. A few similar recipes survive from Greek textbooks on baking and patisserie. These sources say little or nothing about the occasions on which sweets were eaten. For example, whether Cato’s cakes were intended as religious offerings or as a commercial sideline has been a matter of guesswork.

The earliest Greek texts, up to early fifth century b.c.e., suggest that second tables consisted simply of tragemata—“things to be chewed”—raisins, dried figs, dates, hazelnuts, and walnuts. See dried fruit and nuts. This is not the full picture, however. Contemporary vase paintings of feasts show conical or pyramidal cakes on the tables as frequently as they show meat. Thus, coming to the late fifth century, it is no surprise that the comic poet Aristophanes mentions among others a cake named pyramous, which ought, from its name, to be pyramidal. Mentioned about this time are oinoutta, a cake that incorporated must (grape juice) as flavoring and raising agent; melitoutta, which must have been honey soaked; and sesamis, a cake or sweetmeat in which sesame evidently contributed taste and texture.

The next cake of note, first mentioned about 350 b.c.e. by two Greek poets, is plakous. See placenta. At last, we have recipes and a context to go with the name. Plakous is listed as a delicacy for second tables, alongside dried fruits and nuts, by the gastronomic poet Archestratos. He praises the plakous made in Athens because it was soaked in Attic honey from the thyme-covered slopes of Mount Hymettos. His contemporary, the comic poet Antiphanes, tells us the other main ingredients, goat’s cheese and wheat flour. Two centuries later, in Italy, Cato gives an elaborate recipe for placenta (the same name transcribed into Latin), redolent of honey and cheese. The modern Romanian plăcintă and the Viennese Palatschinke, though now quite different from their ancient Greek and Roman ancestor, still bear the same name.

Some of the other cakes for which Cato gives recipes have significant histories, though no others survive under their ancient names. Encytus was unusual in shape and method. It was made by injecting a narrow stream of cheesy batter into hot fat. Already in the fifth century b.c.e. the satirical Greek poet Hipponax noticed, and played on, the analogy between this procedure and the sexual act. Encytus was not in itself sweet, but Cato instructs that it is to be served with honey or with mulsum, the honeyed wine that Romans often drank as an aperitif. The names of Cato’s cakes are all originally Greek, with the single exception of globi, which may have resembled modern zeppole. They were deep-fried in oil or fat and soaked in honey. See fried dough. Their Latin name is shared with that of a geometrical form, from which we know their typical shape: they were spherical or globular. Globi clearly resemble a Greek cake with a quite different name, enkris, mentioned in the sixth century b.c.e. by the archaic poet Stesichoros, perhaps the earliest Greek author to have named any sweet or cake.

Another cake known to Romans and Greeks under different names deserves mention, although Cato omits it—perhaps it was too simple for him. But Galen, a second-century c.e. author on diet and medicine, had watched the frying of pancakes and describes the process carefully. Pancakes (lucunculi in Latin, tagenitai in Greek) recur regularly in ancient writings. Not in themselves sweet, pancakes were served with honey and—as early as Hipponax—sprinkled with sesame seeds. See pancakes.

Cakes were often ritually offered to Greek gods, a gentler form of worship than the slaughtering of a sacrificial animal. Probably people ate the cakes when the ritual was over (but not the pankarpia, an offering of “every kind of fruit” in the form of a honey-soaked cake: herbalists buried this in the ground as thanks giving for rare medicinal plants). We have the names of offertory cakes, but few of the details. Amphiphon was a cheesecake decorated with lighted candles, offered to Artemis the huntress on the full moon of the month Mounychion. Basynias, honey cake garnished with a dried fig and three walnuts, was offered to Iris, the rainbow goddess, on the island of Delos. Myllos, shaped like female genitalia, was offered by the Greeks of Sicily to the goddess Demeter and her lost daughter, abducted from a Sicilian meadow by the underworld god Pluto. There are others: the hebdomos bous or “seventh ox” was offered alongside six phthoeis, but what form did it take? At least the phthoeis can be described: also called selene or “moon,” they were round and white, made with wheat flour, cheese, and honey, and eaten alongside the entrails of a sacrificial animal.

Romans, too, offered cakes to the gods. The commonest Roman offertory cake was a libum, and Cato supplies a recipe for it: cheese, wheat or durum wheat flour, and an egg, all mixed, formed into a large cake, and then placed on bay leaves to bake. There was more than one kind, however: the poet Ovid, in his religious poem Fasti, tells us that millet was an ingredient in the libum offered to Vesta, the goddess of the hearth.

From the fourth century b.c.e. onward, a few narratives of dinners mention the cakes, sweets, and other delicacies that were served at second tables. The oldest is the Dinner of Philoxenos, probably describing an entertainment among the Greeks of fourth-century b.c.e. Sicily. Philoxenos noted sesame cakes and sweets of several kinds (sesame remains a favorite flavor in modern Greek sweets). Then, in early-third-century b.c.e. Macedonia, comes the wedding feast of Karanos, enthusiastically described in a letter by Hippolochos, one of the guests at this lavish—perhaps royal—entertainment. Hippolochos mentions sweets that were local specialities of Greek cities, Cretan, Samian, and Athenian. One of those Cretan sweets might have been gastris, for which a recipe survives in a different source. See gastris.

Fictional narratives of Roman meals give an impression of lavish disorder. Second tables at the overly elaborate “Feast of Trimalchio” in Petronius’s Satyricon were served at least twice, and on both occasions were savory rather than sweet, but they had been preceded by a pompa or set piece, presided over by a pastry Priapus and featuring sweets made to look like fruits and filled with saffron sauce. See priapus. At the meal at Scissa’s, described as an aside in the same episode, a cold scriblita or “cheesecake” was served with hot honey sauce: a good idea, but it arrived among the meats at first tables.

Returning to history, the poet Statius gives us the fullest menu for Roman second tables. In this case, admittedly, there are no tables. Around the year 95 c.e. the emperor Domitian entertained the citizens of Rome to a Saturnalia feast in the Colosseum. Meats were served in hampers; then, as a battle among Amazons was staged in the arena, sweets descended from the skies, including hazelnuts, Syrian dates, Egyptian dates, Damascus prunes, lucunculi, and little Amerine cheeses. Domitian, surely the most generous of imperial hosts, was murdered at his wife’s instigation a year later.

See also cheesecake; dates; dessert; hippocras; and mead.

angel food cake, one of the sweetest and lightest of all cakes, gets its name from its whiteness and cloud-like texture. According to two authoritative sources, the Confectioners’ Journal of April 1883 and Jessup Whitehead’s The American Pastry Cook (1894), angel food cake was created by a St. Louis baker. They do not agree, however, on who this baker was.

Confectioners’ Journal identifies him as Mr. George S. Beers, a frequent contributor to the Journal. The American Pastry Cook simply credits S. Sides. Both sources report that the recipe was for sale. A few months after the April Confectioners’ Journal article, the Journal published an angel food cake recipe without attributing it to anyone.

It turns out that the angel food cake has an earlier beginning than that reported in Confectioners’ Journal. Culinary historian Pat Reber has found mention of a cake called “Angel’s Food” in The Home Messenger Book of Tested Receipts (1878), although that recipe is imprecise. It was not until 1884, when a detailed recipe called Angel Cake appeared in the now-classic Boston Cooking School Cook Book, that angel food cake gained immortality.

Aside from egg whites, flour, sugar, and flavoring, the key to the success of an angel food cake is cream of tartar, an acidic powder derived from sediment produced during wine fermentation; it stabilizes egg whites and contributes to the cake’s volume and whiteness.

By the 1930s the method of making angel food cake and the ratio of ingredients that went into it were firmly established. What had not been determined was the science behind why the cake was such a success.

In 1936 M. A. Barmore approached the topic in a highly technical way. He chose angel food cake because it had few ingredients, and he conducted his experiments in Colorado in a room pressure-adjusted for altitude to over 10,000 feet. He decided to measure the specific gravity of egg whites to determine the optimum for cake volume, the tensile strength of cakes baked at different altitudes, and the effect of oven temperature on the volume and texture of the cakes. He also tested different mixing methods to see which gave the tenderest results.

Barmore found that cream of tartar produced cakes with the finest texture, much better than citric and acetic acids. Baking cakes at different temperatures had minimal effects on texture and volume because the temperature of the cake itself remains fairly constant. For tenderness and cakes with a tight crumb, fresh egg whites proved to be superior to those a few days old. Cakes baked at 10,000 feet were more tender but had less tensile strength than cakes baked at sea level, because of the reduced air pressure.

Another investigator, E. J. Pyler, showed that baking an angel food cake at 450°F (232°C) for 21 minutes produced a cake that rose significantly more than the same batter baked at 325°F (163°C) for 45 minutes. The air cells expand so quickly that the protein meshwork around them is shocked into setting as soon as the cake gains maximum volume.

Other studies revealed that cakes rise best if put into a cold oven before turning it on. Gradual heating allows the air cells to expand less rapidly and slows the setting of the proteins around them, ensuring that the cake will not collapse.

Hanging the baked cake upside down maintains the structure of the air cells as the cake cools. Do not be afraid, though. It will not fall out of the pan while your back is turned.

See also cake.

angelica is the common name for Angelica archangelica, a stout, umbelliferous plant that starts out as a rosette of large (30–70 cm in length), compound leaves with hollow, tubular leaf stalks. In its first year or two (occasionally longer), it will accumulate nutrients in a thick taproot. Then it will flower, set seeds, and die. The green, occasionally purplish, flower stem may grow to a height of 2 m or more. The small, greenish flowers are set in spherical umbels, 10–15 cm or more across. When bruised, the whole plant has a strong aromatic scent, often described as musky.

Angelica is widely cultivated, mainly for its root, in several European countries, including Germany, Belgium, Holland, Poland, and France. Its main uses are in herbal medicine. It was once considered a panacea and used as a remedy for just about every imaginable ailment. Extracts of the roots are utilized in the production of various alcoholic beverages, such as vermouth, Benedictine, Chartreuse, and gin.

Fifty tons of angelica are harvested annually in the marshlands of Marais Poitevin, in the French region of Poitou-Charentes. When grown and prepared here, it may be labeled angélique de Niort. The most common use is to candy the stalks, as confiture d’angélique, for inclusion in cakes and confectionery. The stalks are cut into short pieces and cooked in a sugar syrup several times until saturated. Pure candied angelica is a somewhat dull green. Today it is often artificially colored to make it a gaudy, metallic green. Sulfur dioxide may be added for a longer shelf life. The English trifle is frequently decorated with pieces of candied angelica.

See also candied fruit and trifle.

animal crackers

refer to sweet-tasting crackers molded into the shapes of various circus animals. In the late 1800s animal-shaped cookies (or “biscuits,” in British terminology), called simply “animals,” were introduced from England to the United States. The earliest recipe for “animals” was published on 1 April 1883 by J. D. Hounihan in Secrets of the Bakers and Confectioners’ Trade. It called for “1 bbl [barrel] flour, 40 lbs sugar, 16 lbs lard, 12 oz soda, 8 ozs ammonia,  gals milk.”

gals milk.”

The demand for these cookies grew to the point that commercial American bakers began to produce them. In 1902 the National Biscuit Company officially introduced the most popular brand still known today, Barnum’s Animal Crackers, named after P. T. Barnum (1810–1891), the famous circus owner and showman. The packaging was part of the treat—the box looked like a colorful circus train with animals. Initially designed as a Christmas tree ornament, the string holding the box was soon put to use as a handle by which small children could carry the box around. Although a number of other manufacturers presently make animal crackers, Barnum’s remain the most famous.

Over the years, 37 different animals have been included in Barnum’s Animal Crackers, but the only ones to have survived the product’s entire lifetime are bears, elephants, lions, and tigers. Although child actress Shirley Temple sang “Animal crackers in my soup / Monkeys and rabbits loop the loop” in Curly Top (1935), rabbits never found their way into a box of Barnum’s Animal Crackers. Today, each box contains 22 crackers with 19 different animal shapes: 2 bears (one sitting and one standing), a bison, a camel, a cougar, an elephant, a giraffe, a gorilla, a hippo, a hyena, a kangaroo, a koala, a lion, a monkey, a rhinoceros, a seal, a sheep, a tiger, and a zebra. For the one-hundredth anniversary of the brand, the koala was added on the basis of consumer surveys, beating out the penguin, walrus, and cobra.

Today’s Barnum’s Animal Crackers are baked in a 300-foot-long traveling band oven in a Fair Lawn, New Jersey, bakery belonging to Nabisco Brands. More than 40 million packages of animal crackers are sold each year, both in the United States and in 17 countries abroad. These fun-to-eat treats have remained popular with children and adults, partly because of the many references to animal crackers in popular culture. In addition to Shirley Temple’s song, used in many Nabisco commercials, Animal Crackers was the name of a 1930 Marx Brothers’ musical and film.

See also anthropomorphic and zoomorphic sweets.

animals and sweetness is a subject that has not received much systematic attention. Little is known about why and how human animals evolved their sweet tooth from nonhuman animals. Nonetheless, existing data reveal some surprising and very interesting discoveries for the relatively few animals that have been studied, and it turns out that the ability to discriminate sweets is phylogenetically old. For example, chemotaxic responsiveness (orientation or movement toward or away from certain chemicals along a concentration gradient) to sugars and sweetness has been discovered in motile bacteria such as E. coli.

Evolutionary biologist Jason Cryan notes that humans have evolutionarily and physiologically “associated a sweet taste with high-energy foods which would have helped our earliest ancestors survive better in their environment” (Bramen, 2010). On the other hand, our perception of bitter tastes was important in identifying and avoiding toxic plants. It is possible that one could make the same argument for nonhumans.

Research shows that much variation exists among other animals in terms of their ability to taste sweets. Cats, including lions, tigers, cheetahs, and jaguars, and some other carnivores do not taste sweets and do not show preferences for them. Neither do dolphins, sea lions, or Asian otters. It has been suggested that animals that mainly eat meat do not benefit from eating sweets and have lost their ability to taste sweet foods as a result of genetic mutations. According to Gary Beauchamp, director of the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia, when the data for cats were first published, people claimed that their cats did, in fact, like sweets. However, Beauchamp goes on to explain that the cats’ preference for sweets was really a preference for fat and other components of the sweet items.

Beauchamp further notes that the loss of a taste for sweets occurred independently in different species. An animal’s diet seems to determine whether a mutation will be effective and retained over subsequent generations. Thus, we need to be careful about generalizations across species because domestic dogs, nonhuman primates, spectacled bears, and many other animals prefer natural sugars; and the taste preferences of a large number of species have never been rigorously studied. It is also widely accepted that although domestic dogs do like sweets, the sweets are not good for them.

Interestingly, bees play a significant role in the understanding of human sweet perception and metabolic disorders. Researchers at Arizona State University discovered connections between sugar sensitivity, diabetic physiology and carbohydrate metabolism, and that bees and humans may partially share these connections (“Bees Shed Light,” 2012). By inactivating two genes that control food-related behaviors in the bees’ “master regulator” module, researchers uncovered a possible molecular link between sweet taste perception and the state of internal energy. One of the researchers, Ying Wang, noted that the same bees resembled people with Type 1 diabetes in that both showed high levels of blood sugar and low levels of insulin. Clearly, more research is needed, but the relationship between taste perception in bees and human disease is intriguing. See sugar and health.

It is also known that the brain is not needed to perceive sweetness. Taste scientist Robert Magolskee notes that when researchers put sugar directly into the stomach or small intestine of mice, the mice “know that that’s something good and something positive, and they will seek more of that stimulus” (“Getting a Sense,” 2011).

Data also exist showing that German cockroaches are losing their sweet tooth because the traps used to catch them utilize sugared poisons. The mutant cockroaches have neurons, activated by glucose; some say, “Sweet!” while others say, “Yuck!” The “Yuck!” neurons lessen the signal transmitted from other neurons, so the message “this taste is awful” gets sent to the brain. It takes about 25 generations or 5 years for such a change to occur. This discovery is a compelling example of evolution at work and shows that taste preferences in nonhumans are evolutionarily labile. The rapid emergence of this highly adaptive behavior underscores the plasticity of the sensory system to adapt to rapid environmental change.

There still is much to learn about taste perception and preferences in animals. Existing data offer some unanticipated results among carnivores and other species. Nobel Prize–winning ethologist Niko Tinbergen has suggested that researchers consider four general questions when studying animal behavior: evolution, adaptation, causation, and ontogeny (development). Because eating sweets is enjoyable, psychologist Gordon Burghardt has proposed adding “subjective experience” to Tinbergen’s scheme. Applying Tinbergen’s and Burghardt’s ideas will surely contribute to the database for research on taste preferences and place these sorts of studies in a more naturalistic and comparative evolutionary framework.

See also sweets in human evolution.

anthropomorphic and zoomorphic sweets have, over the centuries, been prepared, bought, and exchanged as presents that add significance to convivial, pagan, and religious celebrations. A wealth of creatures, or parts of their bodies, convey symbolism from the most remote, even pre-totemic times. These sweets are highly aesthetic, as well as delicious and diverse in their ingredients, techniques, intentionality, and meanings. Often they are employed as messengers of mythological beliefs, pagan legends, or episodes of biblical origin, shared through oral tradition and now embedded in updated imagery and practices. Their methods of production and consumption were often recorded in medieval texts. In Spain, writers such as Lope de Vega and Cervantes described them, and the secrets of their production were standardized in treatises on the art of sweet making, such as those by Diego Granado, Martinez Montiño, and Juan de la Mata.

Zoomorphic and anthropomorphic sweets remind us who we are and where we come from. These edible metaphors, vestigial markers of identity often closely tied to festivities, combine tradition with innovation and encourage collective indulgence, as if to prove the truth of the adage “You become what you eat and survive from what you sell.” Whether homemade or bought from convents, stalls in fairs and markets, or from bakeries and cake shops, these ritual sweets offer an opportunity for families and friends to gather and celebrate.

Some anthropomorphic sweets betray the pagan traditions that underlie Christian celebrations, such as Easter sweets that evoke spring fertility rituals. Kulich, the Russian Easter bread replete with candied fruits and drizzled with white icing, is unmistakably phallic, although it is never acknowledged as such. See russia. In Amarante, Portugal, doces fálicos (phallic sweets) are exchanged by men and women during the Festes de Sao Gonçalo in the first week of June, in a sort of fertility rite marking the name day of the patron saint of spinsters. See portugal.

Other anthropomorphic sweets made for particular celebrations include san martino a cavallo cookies with their highly decorative depictions of Saint Martin on horseback, which are baked in Venice on Saint Martin’s Day. Hamantaschen, the triangular filled cookies baked for the Jewish holiday of Purim, are formed in the shape of the Persian vizier Haman’s three-cornered hat. By eating this symbolic hat, the evil Haman is destroyed. See hamantaschen.

Gingerbread men, springerle, Lebkuchen, and speculaas are Central European examples of anthropomorphic cookies, representing figures ranging from Saint Nicholas to an individual family member who inscribes her name in icing on the human shape. Alsatian Gugelhupf is made in various human and animal shapes for different occasions, including that of a swaddled Christ child at Christmas. In pre-Revolutionary Russia during the Christmas season, particularly in the north, decoratively iced animal-shaped cookies made of gingerbread or honey cake were an important part of the caroling ritual. Groups of gaily dressed mummers would proceed from house to house, singing for the cookies as their reward. The most common shapes of these kozuli were deer, eagles, goats, and horses, as well as the sun and human figures. The cookies were also hung on Christmas trees and distributed to children. In the spring, lark-shaped buns (zhavoronki) were baked as harbingers of the new growing season. See christmas; gingerbread; gugelhupf; russia; speculaas; and springerle.

Specific Examples

Anthropomorphic sweets rely on the specific requirements for each type of dough. Some malleable consistencies allow for realistic pieces like orejas de fraile (friar’s ears)—thin, fragile ear shapes. Others, like the brazo de gitano/reina/venus (gypsy’s/queen’s/Venus’s arm), have many layers: the skin, flesh, and blood. Some have protruding parts, such as tetas de novicia (novice’s tits), which are airy with brown meringue on top, or barrigas de fraile (friar’s bellies).

Zoomorphic sweets, on the other hand, require a certain intentionality to produce recognizable figures, whether flat or three-dimensional, like marzipan figures and monas de Pascua (Easter figures) in the shape of swans, dragons, bears, crocodiles, or camels. The monas are made from chocolate in Cataluña. Three-dimensional cakes in the shape of lambs are popular at Easter time in a number of countries across Central Europe; they are baked in special two-part molds. Other types of dough are hand-shaped into two-dimensional figures, traditionally in the shape of snails, oysters, mussels, clams, anchovies, shrimps, crayfish, seahorses, insects, worms, doves, chickens, and swans. Cookie dough has long been popular for making two-dimensional figures, whether imprinted with molds, such as springerle, or formed with cookie cutters, such as gingerbread men. See cookie cutters and cookie molds and stamps. Boiled sugar sweets on sticks, mainly in the shape of roosters but also other animals, have been handmade in Turkey since the sixteenth century. They are often hollow and can be blown as whistles. These confections may have inspired the German roter Zuckerhase (red sugar hares), three-dimensional, bright red rabbit sugar figurines that represent the triumph of life and love at Easter. The many industrially produced sweets made from gelling agents, such as Gummi Bears, are more recent iterations of zoomorphic forms. See gummies and haribo.

In Spain, many sweets are nominally anthropomorphic, their names referring to states of mind. These can be categorized as follows:

Other Spanish sweets are more or less realistic reproductions of bodies or body parts, such as cabello de ángel (angel hair), trenzas (braids), orejas (ears), bocas (mouths), dentaduras (false teeth), bigotes (mustaches), labios (lips), lenguas (tongues), gargantas (throats), corazones (hearts), brazos de gitano (gypsy’s arms), dedos (fingers), tetas de novicia (novice’s tits), barrigas de fraile (friar’s bellies), tripas de monja (nun’s innards), chochos de vieja (old lady’s vulvas), penes (penises), and huesos de santo (saint’s bones).

The most beautiful and delicious of these is cabello de angel (angel hair) that also features as a filling in many other sweets. One seventeenth-century version, made from transparent candied citron, was known as diacitron. Another version is made by pouring liquid egg yolks through a colander with five tiny spouts into boiling syrup, so that the threads of yolk resemble blonde hair. Angel hair is used to adorn trays of luxury cured meats.

Transforming the Fantastic into the Real

Through culinary artistry and the names they give their confections, sweet makers establish a territory of fertile imagination, seduction, and invention. Each edible creature broadens reality, expands the realm of fiction, and embodies the past in the present. The artisans combine the old and the modern, paying tribute to both canonical tradition and heresy, to the local and the universal, to the system of language, to the realm of chance and creativity, and to necessity and survival.

Some historical examples in Spain include animas del purgatorio (souls in purgatory), a version of floating island for which meringues are set onto custard cream colored red with beet juice, and orejones (big ears), a favorite seventeenth-century delicacy that consisted of peaches modeled to resemble ears and then air-dried. The contemporary orejas or orelletes found throughout Spain are very thin, delicate fried sweets in the shape of ears.

Even today, when home cooks bake round loaves of ancient simplicity based on the Roman panis candius, they give a piece of dough to children for them to create their own edible amulets, thereby accentuating the magical and religious dimension of bread as a sacred element offered in social and religious celebrations. The children’s doves, lizards, and snails are drizzled with olive oil and sprinkled with sugar before being baked until brown and crunchy.

Mysteriously, two very old zoomorphic sweets from distant regions in Spain, the Majorcan ensaimada and the anguila de mazapán (marzipan eel) from Toledo, share the same snail shape of coiled dough. The Majorcan pastry is of Christian origin, because its hojaldre dough is made with pork fat; the Toledan anguila has Semitic roots. We must suspect that its name is a euphemism to avoid mentioning a taboo: the serpent. Magnificently stuffed with sweet potato, almond paste, and egg yolk with syrup, and ornamented in the style of Toledan filigree, the expensive anguila symbolizes power and wealth. It appears at Christmas surrounded by marzipan figurines and turrón (nougat candy), heralding a dense calendar of festive opportunities to cultivate the idiosyncratic Spanish passion for embellishing everyday life, to exchange gifts with peers, reward moral authorities, show appreciation to donors, and request intercession from the spheres of sanctity and deity. See nougat and spain.

The Emergence of Thematic Sweets in Spain

The immensely contrasting regions of Spain have been enriched by a convivial crush of various ethnicities. Native Tartessians and Iberians saw the arrival and challenge of Celts, Greeks, Romans, Jews, Visigoths, Moors, other Europeans, and Americans, all exchanging material culture such as ingredients, instruments, and techniques, as well as the wealth of their conceptual imagery. Primal sobriety, isolation and poverty, then classicism, followed in 711 by the sudden impact of the Arabic sense of refined luxury, established a culinary wisdom reflecting the synthesis of three cultures: Moorish, Jewish, and Christian. Marzipan and zoomorphic marzipan figures are Semitic in origin. See marzipan. From the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries, symbols of political and economic power were imported from Italy and found their way into kitchen and dining room. The tables of nobles and kings were invaded by monumental scenes of heroic animals and humans at leisure or in combat, cast of sugar, pastry, or marzipan and decorated with arabesques and pan de oro (gold foil), and colored with fancy substances such as cochineal and sandalwood, as described in the literature of the period. See food colorings and sugar sculpture.

Everyday Spanish life is still marked by festive conviviality featuring music and food. Spaniards are prepared to invest time, energy, and money in celebrating rites of passage from birth to death, as well as the sequence of religious festivals aimed to incur the favor of God and the saints. The public is also given the opportunity to spend and celebrate at regular commercial events, such as local fairs and markets, during which ancestral traditions of producing and eating certain sweets are revived as an excuse for commerce and socializing. The bone-shaped sweets that appear in the streets and markets on All Saints Day are one example. Huesos de santo are made of marzipan with different fillings; huesos de San Expedito are fried; and other “bones” look broken because they are reliquias (relics). See day of the dead; fairs; and festivals.

Why, where, and how these sweets survive depend on the producers. Their champions are to be found in the home—the mothers and grandmothers and the children who learn from them—and at the closed convents where the monjas de clausura sell their divine specialties. See convent sweets. Professional bakers also deserve special mention for their perseverance, mindful as they are of their role as the keepers of sweet-making traditions, and tied up as they are in their own means of survival. The true enemies of the fantastic tradition of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic sweets are the changes in the availability and quality of basic ingredients, and the contemporary panic over diet and nutrition.

See also animal crackers; easter; fried dough; and holiday sweets.