ice cream, the frozen mixture of sweetened and flavored cream or milk that is so universal today, was a precious indulgence when “One plate of Ice cream” was served at the table of King Charles II in 1671, according to Elias Ashmole’s account in The Institution, Laws and Ceremonies of the Most Noble Order of the Garter, published a year later. At the time, kings, queens, and nobles might dine on ice cream. Commoners did not. Until the late eighteenth to early nineteenth century, the expense and difficulty of making ice cream limited it to upper-class tables.

Despite mythmakers’ tales, neither Marco Polo nor Catherine de Médici introduced ice cream to European courts. Freezing is not described in Europe until the sixteenth century, and only then by scientists rather than cooks. Serving a plate of ice cream was not possible until the discovery of the endothermic effect, whereby a substance, such as cream, can be made to freeze by immersing or surrounding it with a mixture of ice and salt. Surrounding a cream mixture with ice alone chills but does not freeze it. Adding salt lowers the melting point of the ice and draws heat out of the cream, causing it to freeze. This mechanism, if not ice cream, was familiar as early as the thirteenth century, according to a contemporary description of the process by Arab medical historian Ibn Abu Usaybia.

Prior to the discovery of the technique of freezing, ice and snow were sought after and highly valued. Harvesting and then storing ice and snow for any length of time presented difficult challenges, but that simply added to the chilly substances’ desirability. Ice was so highly regarded that a holiday was created for it in fourth-century Japan. On that day, the emperor gave chips of ice to palace guests. In ancient times, the Chinese, the Greeks, and the Romans all gathered and stored ice or snow. Icy sherbet drinks date back to medieval times in the Middle East. In the fifteenth century, the elites of Spain and Italy sent their servants to nearby mountains to gather snow. The servants wrapped the snow in straw and carried it back, on mules’ backs or on their own. They stored whatever had not melted in pits or in simple icehouses built into the ground in cool, shaded areas. The ice and snow were used to chill drinks, decorate tables, and crown foods.

It seemed as if the world was waiting for ice cream to be created, despite the fact that from China to India to the Middle East and Europe, traditional medical and nutritional beliefs opposed iciness in the diet. Eating or drinking anything that was either exceptionally hot or cold was supposed to be avoided. Hippocrates had warned against “cold things, such as snow and ice,” because they were “inimical to the chest.” At various times and places, iced drinks were said to cause such ailments as colic, convulsions, paralysis, blindness, and even death. As late as the seventeenth century, the English diarist John Evelyn said he suffered “an Angina & sore Throat” because he had drunk wine with “Snow & Ice as the manner here is” when he was in Padua. Yet despite all the warnings and objections, ice and snow were prized and the discovery of the technique of freezing was acclaimed.

From Slush to Iced Cream

In the sixteenth century, the Italian scientist Giambattista della Porta experimented with freezing wine because, he wrote, “the chief thing desired at feasts” was wine as cold as ice. To freeze the wine, he immersed the bottle in a container of snow and saltpeter and turned the bottle until the contents froze. Since alcohol does not freeze solid, the result was a slushy drink that was soon the toast of noble Roman tables.

The freezing process made fanciful ice artistry possible. Cooks created marzipan boats and set them afloat on seas of ice. See marzipan. They dipped fresh fruits in water, froze them, and displayed the shimmering fruits on dinner tables. Finally, they created sorbets and ice creams.

Cooks were already experienced in making flavorful drinks like the Middle Eastern sherbets. See sherbet. Their repertoire also included an enormous variety of cream and custard dishes. See cream and custard. The next step was to turn these drinks into ices and the creams into ice creams.

In the latter half of the seventeenth century, ices began appearing in Italy, France, and Spain. Antonio Latini, chief steward for the Spanish prime minister in Naples, published some of the earliest recipes for ices, including one made with milk, in Lo scalco all moderna (1692). At the time, he also claimed that everyone in Naples knew how to make them. “Everyone” was, no doubt, an exaggeration. See latini, antonio. But others in Naples and in France were beginning to publish recipes. Nicolas Audiger included detailed freezing instructions in his book La maison réglée, published the same year as Latini’s first volume. Audiger did not have specific recipes for ices; he simply explained that to turn a drink like lemonade into an ice, one should double the sugar. Unlike Latini, however, he did give detailed instruction on how to freeze this doubly sweet lemonade. He said it should be put in a container, covered, and placed in a large tub filled with crushed ice and salt. After letting the container sit in the tub for a time, one should open it and stir the contents. The process should be repeated until the beverage turned into a sorbet. Though machine churning has replaced stirring by hand, the principle remains the same: moving the mixture as it freezes ensures that it will not simply harden into a block of flavored ice, but will be smooth and scoopable.

Audiger had just one recipe for ice cream. It was made with cream, sugar, and orange flower water, a delicate flavor that deserves a renaissance. See flower waters. Other cooks published recipes for iced creams at the time, but their freezing instructions often failed to mention the all-important churning. The first ice cream recipe in an English cookbook appeared in Mrs. Mary Eales’s Receipts, published in 1718. Titled “To Ice Cream,” the recipe did not mention stirring.

Many early ice cream recipes seem tentative, as if the writer is not completely confident about the process. But in the eighteenth century, cooks became so comfortable with it that they experimented with flavors.

Confectioners’ Creations

In France, in 1786, M. Emy wrote the first book entirely devoted to ices and ice creams and the most comprehensive one for generations. See emy, m. His ice cream flavors ranged from cinnamon to saffron. His ices included pineapple, pomegranate, and rose. He also molded his ices and ice creams into decorative shapes.

Other confectioners began to do the same. Using molds of various shapes and sizes, they created realistic-looking peaches, strawberries, and pears to reflect the flavor of the ice or ice cream. They also molded ice cream into representations of hams, fish, and chickens that, happily, had nothing to do with the flavor of the ice cream.

They became so skilled at these trompe l’oeil ices that some eighteenth-century confectioners used them to trick guests. Dr. John Moore, an English resident of Naples, described a meal composed of ices in his 1792 book A View of Society and Manners in Italy. He wrote that when the king and queen of Naples paid a call on the nuns at a nearby convent, the royal party was presented with what looked like a cold luncheon consisting of meats, poultry, and vegetables. To their delight, the guests discovered the turkey was, in fact, a lemon ice, and all the other dishes were also ices in disguise. See trompe l’oeil.

In the nineteenth century, British confectioners made ice cream in the shape of anarchists’ bombs with flames made of spun sugar flaring from the top. The editors of The Encyclopaedia of Practical Cookery thought it “remarkable how much inclined some culinary professionals are to introduce the arts of warfare into their peaceful and uneventful occupations.” The London-based Italian confectioner Giuliagmo Jarrin is credited with coining the term bomba to describe such ice creams. See jarrin, william alexis.

America was slow to jump on the ice cream bandwagon. The cost and difficulty of obtaining ice along with the price of sugar meant that few could afford ice cream. Thomas Jefferson, for one, liked ice cream so much that he brought a recipe home from France and had his ice cream made at Monticello, where he maintained an icehouse. But few had the financial resources for their own ice house, and even professional confectioners could not get enough supplies to guarantee ice cream every day. Still, a certain Philip Lenzi advertised in a 1777 edition of the New York Gazette that he had ice cream to sell “almost every day.”

Like ice and sugar, domestic ice cream recipes were hard to come by. Though imported and reprinted English cookbooks, such as the American edition of The New Art of Cookery (1792), included some recipes, Mary Randolph’s The Virginia House-Wife, published in 1824, was the first native cookbook to offer recipes for ice cream and ices. Her many flavors included almond, chocolate, vanilla, and coconut. Most were flavors we enjoy today; the one oddity was her recipe for frozen oyster cream.

During the early nineteenth century, as ice cream became more affordable and available, Americans could buy it from confectioners, at cafés, and at pleasure gardens. These outdoor areas, long popular in England, were a cross between a garden and a café where patrons paid admission to stroll along tree-lined walkways, listen to musicians play, and enjoy delicacies like pound cake, lemonade, ices, and ice creams. Initially, the gardens were genteel havens for ladies and gentlemen, but eventually they became more democratic. Some served liquor and allowed dancing.

By the middle of the century, ice cream shops had opened in major cities. Some were tastefully decorated and catered to ladies by serving tea, sandwiches, and such drinks as sherry cobblers in addition to ice creams. Less elegant and expensive shops catered to working-class customers.

Egalitarian Ice Cream

In the era before mechanical refrigeration, ice had been as important an ingredient in ice cream making as cream, but supplying it was hardly big business. Like many others, Frederick Tudor’s family harvested ice from a pond on their property near Boston, Massachusetts, and used it to make ice cream. Tudor saw the business possibilities in ice harvesting and decided to sell the ice in the West Indies. Despite a lack of interest from investors, he obtained the right to sell ice in Martinique in 1806, harvested enough to fill a ship, and set sail. The venture was a financial failure: much of the ice melted en route; moreover, Frederick’s brothers, who had gone ahead to make arrangements, failed to provide an icehouse for storage once the shipment arrived. Nevertheless, Tudor persuaded a local restaurant owner to use the rapidly diminishing ice to make ice cream, and the local newspaper hailed his achievement.

In subsequent years Tudor and his associate Nathaniel Wyeth developed new harvesting, shipping, and storage techniques and ultimately shipped ice as far as India successfully (the Ice House in Chennai, India, still stands). Tudor became known as the “Ice King.” His success inspired competitors, and by 1879 the natural ice industry was harvesting nearly 8 million tons of ice annually, employing thousands of men, and delivering ice to businesses and homes nearly everywhere. An icebox became a must-have kitchen appliance, and ice cream an affordable treat for ordinary families.

As the ice industry was developing, another innovation helped make ice cream a household item in the United States—an ice cream freezer that allowed the mixture to be stirred without the need to open the pot. In 1843 Nancy Johnson, a Philadelphian about whom little else is known, patented an ice cream freezer intended for home use. A crank on the outside of the tub was attached to a dasher, or paddle, inside the freezing pot. The person making the ice cream turned the crank, and the inner dasher churned the ice cream to a smooth, lush consistency. Others soon followed Johnson’s lead and produced so-called patent freezers, which made it more cost-effective for professionals to make ice cream and much easier for home cooks to do the same. See ice cream makers.

By the late nineteenth century, ice cream making at home was widespread. Ice cream became as essential to birthday celebrations as cake. It went on picnics and raised funds for churches at ice cream socials. See ice cream socials. Cookbooks abounded with recipes, and home cooks began emulating confectioners by molding their ice creams. Molds were sold in general stores and could be ordered from catalogs. Cookbook writers advised those who could not afford molds to improvise by using household items like baking powder cans. See molds, jelly and ice cream.

Expanding Opportunities

Commercial ice cream making expanded rapidly. In 1851 Jacob Fussell, a milk dealer from Maryland, was faced with an oversupply of cream. Rather than let it sour, he turned it into ice cream and sold it at a price that undercut the city’s confectioners. Recognizing the potential of the ice cream business, he opened a factory and began production. Within a few years, he had become the first significant ice cream wholesaler in the country, selling to hotels, restaurants, and even churches. When his associate James M. Horton took over the business in 1874, he became the first to ship ice cream to foreign ports. Thereafter, ice cream was a favorite dessert aboard transatlantic steamships.

The United States had been late to ice cream making but, after the end of the Civil War, it led the world. European wholesalers bought American ice cream–making equipment, copied American products, and used American marketing techniques. Inexpensive ices and ice creams proliferated, and elite confectioners felt threatened by the competition. An 1883 edition of the Confectioners’ Journal warned against the “fraudulent and depraved wares of the factories.” It was no use. By then, street vendors were selling ice creams for pennies.

Italian immigrants in England and in the United States found work as ice cream peddlers in the late nineteenth century. Their ice cream was not of the same quality as that sold by confectioners, but it was welcomed by those who had never been able to afford any sort of ice cream. The peddlers sold ice cream in small glass containers called penny licks. They filled a glass with ice cream and the customer licked it out, without benefit of a spoon. When he finished, the peddler wiped the glass with a rag and filled it up for the next customer.

Somewhat more sanitary products were soon developed. Hokey-pokeys were slices cut from a brick of ice cream and wrapped in a piece of paper. Usually, the bricks were layered with three different flavors; each crosswise slice revealed all three, much to the delight of children. Ice cream sandwiches, first created by a street vendor on New York City’s Bowery, soon became a favorite street food. Confectioners copied the idea, but served the sandwiches on small plates with ice cream forks. Forks were just one of the specialized implements created for ice cream. By the turn of the century, ice cream knives, spoons, dishes, bowls, serving pieces, and scoops all flourished. See serving pieces.

The ice cream cone was originally eaten with a fork and served on the most elegant tables. See ice cream cones. Mrs. Agnes Marshall was an English cookbook author, teacher, and entrepreneur whose 1894 book Fancy Ices contained several recipes for prettily decorated ice cream cones. In one illustration, the ice cream cones are arranged in a pyramid atop a doily-covered platter. See marshall, agnes bertha.

In 1902 Antonio Valvona, an Italian living in England, received a U.S. patent for his “apparatus for baking biscuit-cups for ice-cream.” He said they were to be “sold by the vendors of ice-cream in public thoroughfares.” When ice cream cones were sold at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri, they became an instant and widespread hit.

Initially, soda fountain proprietors resisted adding ice cream to their inventory because of the expense and difficulty of storage. It was inevitable, though, and before long ice cream sodas, sundaes, floats, banana splits, and other treats all became popular soda fountain offerings. The temperance movement and, later, Prohibition benefited the business greatly as soda fountains replaced saloons, and brewers became ice cream manufacturers. See soda fountain.

Street vendors’ offerings expanded to include ice cream novelties such as Eskimo Pies, Good Humor bars, Popsicles (called Ice Lollies in England), and many others. See eskimo pie; good humor man; and popsicle.

The Frozen Dessert Business

Ice cream–making equipment had improved over the years, and quantity production was possible by the early part of the twentieth century. By 1910 continuous-process freezers could produce up to 150 gallons of ice cream an hour. During World War I, ice cream making was banned in England. In the United States, sugar was restricted, so ice cream makers began replacing some of it with corn syrup and corn sugar. See corn syrup. Some manufacturers used powdered milk and butter in place of the more expensive fresh cream. When the war ended, some substitutions continued.

In the 1920s mechanical refrigeration began to do away with the need for ice and salt, and before long with the natural ice industry. See refrigeration. Refrigerated railroad cars sped national distribution. Technological advances including steam power, electric motors, homogenizers, and packing machines increased production capabilities. Scientific formulas designed to achieve specific butterfat content replaced old-fashioned recipes.

Howard Johnson opened his first soda fountain in 1925 in Quincy, Massachusetts, and soon became famous for the high quality of his ice cream, its 28 flavors, and the shops’ highly visible bright orange roofs. One of the first to recognize the advantages of restaurant franchising, Johnson grew his business to include restaurants and hotels from Maine to Florida.

The Depression hit the ice cream industry hard, but portion control and other cost-cutting measures helped. So did offering customers a bargain. Five-cent cones and other nickel novelties were not very profitable, but they kept customers coming back. When the Depression ended, the ice cream business surged.

During World War II, England again prohibited ice cream making, as did Italy. But in the United States, ice cream was considered a morale builder and symbol of patriotism, thanks in large part to industry lobbying. In 1943 the U.S. Armed Forces became the world’s largest ice cream manufacturer. The civilian business prospered as well, despite the rationing of some ingredients and difficulty of obtaining others. Before the war, quality ice cream had been made with a butterfat content of 14 percent. During the war, it dropped to 10 percent, and fewer flavors were produced to save on containers and transportation. Sherbet, or ice milk, was often served in lieu of ice cream. When the war ended, many manufacturers continued to make ice cream the same way.

After the war, munitions factories switched to turning out new cars and refrigerators with small freezing compartments. Homemakers began driving to the new supermarkets for their ice cream or going to drive-in soft-serve shops, instead of the local drugstore soda fountain. Prepackaged half-gallons of ice cream became the norm. Bigger was better, and quantity won over quality.

Before long, though, the tide turned, and companies such as Baskin-Robbins and Häagen-Dazs began to make richer, creamier ice cream. Young entrepreneurs like Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield, of Ben & Jerry’s fame, opened scoop shops and sold rich creamy ice cream in an assortment of flavors. See baskin-robbins; häagen-dazs; and ben & jerry’s. In 1981 TIME Magazine pronounced ice cream “our guiltiest and most delicious sin.”

In the twenty-first century, the frozen dessert business has become a vast multinational, multi-billion-dollar enterprise dominated by international conglomerates Unilever and Nestlé. See nestlé. Not every frozen dessert has a strict definition, but in general the market includes regular ice cream, which the United States Food and Drug Administration defines as containing not less than 10 percent milkfat; premium and super-premium ice creams, which can contain 18 percent; and French ice cream or frozen custard, which is made with at least 1.4 percent egg yolk solids. Although no hard-and-fast rule exists, sherbet is usually defined as a frozen, fruit-flavored dessert made with milk, whereas sorbet, often referred to as an ice, is made without milk. Gelato, or Italian ice cream, is generally lower in fat than most ice creams, and since it is served at a warmer temperature, its flavor may be more intense. Soft-serve is ice cream served as it is churned rather than being hard-frozen.

Today, in addition to finding ice cream at supermarkets, frozen dessert lovers can indulge at local scoop shops and new chain stores that are creating ice cream, gelato, frozen yogurt, and sophisticated soft-serve ice creams in all kinds of flavors. Although in every large-scale poll the most popular flavor continues to be vanilla, today’s shops feature flavors ranging from Secret Breakfast, made with cornflakes and bourbon, to Honey Jalapěno Pickle. There has also been a resurgence of homemade ice cream, thanks to ice cream makers that work with the press of a button.

See also cream; italian ice; medicinal uses of sugar; and sundae.

ice cream cones are edible cone-shaped pastries designed to hold ice creams or ices. Although their origins are controversial, the most plausible explanation is one of simple evolution. Ice cream manufacturers, faced with the challenge of creating a container, at the lowest possible cost, turned their skills as confectioners to adapting wafers to a new use.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, ice creams were rare and served only in aristocratic or wealthy households. They were eaten by the wealthy out of small porcelain, glass, silver, and pewter cups on a small plate, frequently with a small spoon.

The earliest reference to cones or cornets was by Antonio de Rossi, a Venetian confectioner in Rome, who produced, in 1724, a manuscript of recipes, including one for cialdoni torcerli or twisted wafers, which were shaped into conical containers, or cones.

The first pictorial evidence for ice cream cones is seen in an 1807 print by Debucourt showing a woman eating an ice in a cone in M. Garchi’s casino café Frascati, in Paris.

Mrs. Agnes Marshall’s Fancy Ices from 1894 offers two recipes for ice cream cones, the first known recipes published in English. Her Christina cornets were filled with vanilla ice cream mixed with finely diced, dried fruits. The cornets were piped with royal icing and dipped in chopped pistachio nuts. Her Margaret cornets were half-filled with ginger water ice, the other half with apple ice cream. Both were to be served “for a dinner sweet or dessert.” See marshall, agnes bertha.

Numerous claims exist in the United States that the ice cream cone, or cornucopia, was invented at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri. The fair popularized the cone, but it had already been in use in Europe many years before. Prior to the invention of the cone or cornet, the “penny lick” was the container in which ices were sold in Great Britain at the seaside and in the streets of towns and cities. Smaller sizes were sold for ½ d (halfpenny lick) and ¼ d (farthing lick). The “penny lick” was a small, low-quality, usually footed glass with a partially solid bowl and a small recess to hold the ice. The ice cream was “licked” out and the glass then returned to the vendor, who used it for the next buyer, frequently without washing it. These glasses were banned in England in the 1920s for spreading tuberculosis.

Waffle and sugar cones are variations on the simple cone, the waffle one being thicker and the sugar one containing more sugar, which gives it a firmer and more brittle texture. The Italian manufacturer Spica invented the Cornetto in Naples in 1959. The inside of this cone is coated with chocolate, sugar, and oil, making it possible to freeze the cone complete and filled, a technique that keeps it from becoming soggy. The Cornetto is one of the most successful ice cream products in the world. Spica is now owned by Unilever.

The ice cream cone is a convenient way to eat ice cream, but it is also one of the most ecologically sound pieces of packaging ever invented, since one consumes it.

See also ice cream.

ice cream makers in the form of hand-cranked freezers were patented in the 1840s by a Philadelphia woman and a London confectioner. Their inventions revolutionized ice cream by creating a smooth, creamy texture that previous freezing methods did not produce. Other inventors improved upon their designs to create better ice cream makers for both household and commercial use.

In the ancient world, people used snow and ice to cool foods, but these natural refrigerants were in short supply during hot weather. Early scientists searched for a more reliable coolant, and someone discovered that putting saltpeter (potassium nitrate) in water produced a very cold liquid. By the mid-sixteenth century, Italians knew about this phenomenon and used it to make frozen concoctions called ices. See italian ice. The French also learned the secret, and recipes for ices were published in Europe before 1700.

Until the 1840s, cooks used the pot freezer method to make ice cream. First, the cook removed ice from the icehouse or pit where large blocks of harvested natural ice were stored. He chipped the ice into small pieces and placed the chips, along with salt or saltpeter, into a wood tub. Then he poured his ice cream mixture into a tin or pewter pot and set it in the tub. He rotated the pot by hand and periodically used a long spoon to mix up the frozen particles inside the pot. His goal was to make a smooth frozen cream, but he generally produced a slushy concoction more icy than creamy.

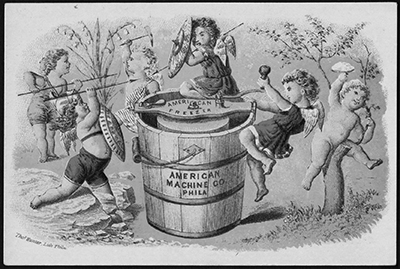

The American Machine Co. of Philadelphia manufactured the Gem Ice Cream Freezer in sizes ranging from two to fourteen quarts. This late-nineteenth-century advertising card shows how the cedar pail and stirrer move in opposite directions, causing “double action” that beats the ice cream mixture. boston public library

In a variation on the pot freezer method, French cooks used a special pot or canister, called a sorbetière, which fit into a tall, cylindrical wood tub. The metal canister had a tight-fitting lid with a handle, which the cook grasped and turned to rotate the pot inside the tub. From time to time, the cook removed the lid and stirred the canister’s ingredients with a spoon or spatula. Thomas Jefferson saw sorbetières when he lived in France (1784–1789) and acquired one for Monticello, his Virginia plantation.

In 1843 Nancy Johnson was issued a U.S. patent for a hand-cranked freezer, and Thomas Masters received a British patent for a design similar to hers. Johnson’s device had four parts: a wood tub that held the salt and ice, a metal canister that held the ice cream mixture, a paddle or dasher that fit inside the canister, and a crank that attached to the dasher. The cook turned the crank, which rotated the dasher, churning the ice cream mixture inside the canister. The constant churning produced a frozen cream with a smooth, uniform texture.

Variations on Johnson’s design were used for both home and commercial ice cream making in the nineteenth century. In the early 1900s, inventors patented special freezers for commercial ice cream manufacturing plants. These new freezers were designed for continuous, efficient production of large quantities of ice cream for the marketplace.

Electricity and mechanical refrigeration turned the hand-cranked ice cream freezer into an endangered species in the home. Families who could afford the latest labor-saving devices threw the old-fashioned freezer on the trash heap. New versions of the tub-and-canister freezer used an electric motor to turn the dasher, thereby eliminating the tedious, tiring hand-cranking. Another labor-saving option was making ice cream in the freezer compartment of a refrigerator. By the late twentieth century, cooks had a wide choice of efficient, easy-to-use ice cream freezers.

A compact, modern version of the hand-cranked freezer utilizes a double-walled bowl; the coolant is sealed between the walls, eliminating the messy, melting ice and salt. The cook puts the bowl in the freezer compartment of a refrigerator to freeze the coolant. Then the bowl is filled with the ice cream mixture and placed inside the housing. Like an old-fashioned freezer, this countertop version has a handle and a dasher. At intervals the cook turns the handle to stir the mixture and facilitate freezing.

Another option is the small electric ice cream maker that works in the freezer compartment of a refrigerator. The unit has paddles that turn slowly and automatically shut off while the ice cream is still soft. The ice cream ripens and hardens in the freezer. Some refrigerator manufacturers offer a built-in ice cream maker or a special electrical socket for one. Cordless, battery-operated ice cream makers have also been designed for use in the freezer compartment.

In the early twenty-first century, the most expensive ice cream maker is the self-contained freezer compressor unit. The cook prepares the ice cream mixture and presses a button to start the machine, the epitome of convenience and modernity. But the old-fashioned hand-cranked freezer is not totally extinct. At least one company still markets a hand-cranked freezer much like Nancy Johnson’s, because many food lovers believe that hand-cranking makes the very best ice cream.

See also emy, m.; ice cream; marshall, agnes bertha; and refrigeration.

ice cream socials became popular in late-nineteenth-century America as a result of the temperance movement, technology, and fundraising. Seeking sober alternatives to socializing, and employing ever-cheaper mechanical ice cream makers plus advances in commercial ice harvesting and storage, churches, synagogues, lodges, youth and other social clubs sponsored events based on selling ice cream to provide ongoing financial support for their organizations.

Offering usually a limited menu of flavors, and cake or pie to accompany the ice cream, the groups sold and served plates of ice cream to customers who, in summer, often sat at tables outdoors in imitation of popular commercial ice cream gardens, or in church fellowship or social halls converted for the event to ice cream parlors. The social might be timed to coincide with a community celebration or anniversary, with a holiday like the Fourth of July, or with a food festival such as those celebrating strawberries or blueberries. The social might also include music and games, with prizes for winners.

For centuries before the mid-1800s, ice cream had been an elite food, dependent on sufficient resources to buy or harvest and store ice for warmer seasons, plus household labor to make the treat. The invention of a geared, hand-cranked ice cream maker, patented in 1843 and thereafter manufactured for household consumption, put ice cream–making technology into middle-class domestic and social settings. See ice cream makers. Concomitantly, a trade in commercial ice harvesting ensured a year-round supply of natural ice, which was gradually replaced by the development of artificial refrigeration and ice production, particularly in the early twentieth century. See refrigeration. These technologies, coupled with increased mid-nineteenth-century specialization in dairy farming near developing town and urban centers that assured regular supplies of milk and cream, plus ever-cheaper sugar, made ice cream popular among all strata of American society.

Recipes for ice cream abound in late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century cookbooks, and some, like Sarah Tyson Rorer’s Ice Creams, Water Ices, Frozen Puddings, published in 1913, specifically addressed ice cream in all its forms. From time to time, large-quantity recipes for ice cream, pointing to production for socials, appear in community cookbooks published by charitable organizations to raise money. Occasionally, too, in manuscript cookbooks or hand-written recipe collections, ice cream recipes titled “for the church freezer,” which call for larger quantities than a cook might make for family enjoyment, can be found.

Per-capita American ice cream consumption peaked during Prohibition in the 1920s. Ice cream socials were the epitome of good clean fun and continued well past the 1930s into the mid-twentieth century, especially among organizations dedicated to continued temperance, religious activity, or entertainment for youth. Groups, especially in rural areas, continued making their own ice cream, while those with access to commercially produced ice cream switched to buying it. Church and social groups still make ice cream for socials today, though ever more rarely.

See also ice cream.

icebox cake, made from cookies or sweet crackers spread with whipped cream and chilled to form a solid, sliceable mass, descends from a 200-year-old family of desserts that includes trifles and charlottes. See charlotte and trifle. Popularized by the proliferation of refrigerators (ice cooled in the later nineteenth century, then powered by gas or electricity in the early twentieth century), these desserts were promoted via cookbooks published by refrigerator makers, such as Alice Bradley’s 1927 Electric Refrigerator Menus and Recipes: Recipes prepared especially for the General Electric Refrigerator. See refrigeration. Magazines, newspapers, and cookbooks also provided recipes for icebox treats.

Early-twentieth-century versions of icebox cake often called for layers of ladyfingers or pieces of sponge or angel food cake dipped into custard prior to chilling in a form. See angel food cake and sponge cake. By the early 1930s, icebox cakes commonly used commercial cookies like vanilla wafers and chocolate wafers, layered with whipped cream.

Icebox cake precedents, such as the trifle in Hannah Glasse’s 1805 Art of Cookery, call for macarons and cookie-like sweet cakes softened with sherry, topped with custard and jelly, and moistened further with syllabub, a wine-flavored whipped cream. See macarons and syllabub. In the later 1800s, versions of charlotte russe sometimes called for gelatin-fortified whipped cream used with cake. See gelatin. Maria Parloa’s Charlotte Russe No. 2 recipe in her 1880 New Cookbook and Marketing Guide pointed the way to icebox cake with these instructions: “Have a quart mould lined with stale sponge cake. Fill it with whipped cream and set it in the ice chest for an hour or two.”

See also cake.

icing is a sugar-based medium for enhancing and decorating many types of cake and other sweetmeats. Although a plain cake should still taste superb, it is often the icing on the cake that identifies it. Would we recognize an American carrot cake, the Dobos torta from Hungary, or a traditional British Christmas cake without their decorative layer of sugar?

Our love of sweetness may not be innate, but it is certainly ancient: honey brushed over an oven-hot cake was recommended in the fifth century by Apicius. Until smoothly ground icing sugar, or confectioner’s sugar, was produced by commercial refineries in the nineteenth century, it was necessary to crush lump sugar in a mortar, then brush or shake the powdery grains through a fine-meshed cloth or sieve two or three times. See sugar and sugar refining.

Robert May’s (1685) simple sugar glaze made by boiling sugar and water was poured over a newly baked fruitcake before drying in the oven. See fruitcake. A layer of icing provides extra sweetness and also seals in the moisture and flavor of a cake. Ralph Ayres (1721), the cook at New College, Oxford, prepared the icing for a plum cake by beating sugar with egg whites for “half an hour or longer,” thereby presaging present-day practice.

Ayres’s icing was known as sugar icing until 1840, when Queen Victoria’s wedding cake, weighing 300 pounds, was created. See wedding cake. To mark the occasion, the sugar plus egg white icing that covered the elaborately decorated and tiered confection was renamed “royal icing.” Royal icing spread over marzipan on a rich fruitcake has become the accepted style for a celebration cake. The smooth, firm surface obtainable with royal icing is well suited to cake decoration involving piped emblems such as flowers, swags, and trellis patterns. See cake decorating.

Both Mrs. Raffald (1769) and Mrs. Beeton (1861) refer to the marzipan on a cake as almond icing, now also known as almond paste. See beeton, isabella and marzipan. Blanched and ground almonds are mixed with icing sugar, egg whites, lemon juice, and brandy or rosewater to make a firm dough that is rolled out and placed on top of the cake. An English Simnel Cake has one layer of marzipan baked into the center and another resting on top of the cake. For a Battenberg Cake, the sections of colored sponge cake are held together by a sheet of marzipan enveloping the whole cake.

In the window of any French patisserie are examples of glacé icing with individual tarts, choux pastry éclairs, and sponge cakes gleaming with the smooth, satiny mixture. This soft icing is made by beating icing sugar with sufficient hot water until spreadable; it is usually flavored with vanilla extract, black coffee, chocolate, or citrus juice. Glacé icing is widely used by home bakers to give a professional finish to a cake.

In her chapter on pastes, icings, and glazes, Mrs. A. B. Marshall (1888), founder of a famous London cookery school, includes Vienna icing, made by blending icing sugar with butter, brandy, and maraschino. See marshall, agnes bertha. This icing is known today as buttercream or buttercream frosting, with milk or cream replacing the alcohol in Mrs. Marshall’s recipe. Vienna icing “may be flavoured and coloured according to taste,” says the author, and cupcake makers worldwide have risen to the challenge with a layer of various buttercreams, from lavender to pistachio, spread over the little paper-cased cakes. See cupcakes.

Not all icings require icing sugar. The different stages of boiled sugar syrup are deployed in making some frostings and icings, such as the billowing white meringue of American boiled icing. See meringue and stages of sugar syrup. Also described as seven-minute frosting, this icing is made by slowly adding a 238°F (115°C) sugar syrup to stiffly whisked egg whites while constantly beating until cool, usually for seven minutes.

Cooking a clear sugar syrup until it changes color to pale amber produces the glassy caramel icing of some Austrian and Hungarian cakes, such as Dobos torte. See dobos torte. The liquid caramel is either spread thinly over the top of the cake or poured onto oiled paper and allowed to cool before cutting to shape for decorating the cake.

Naturally brown cane sugars such as muscovado and demerara contribute an excellent butterscotch flavor to icing. Light, soft brown sugar is dissolved in heavy cream or butter over low heat, then brought to the boil and slightly cooled to produce an attractive fudge-like frosting. See sugar.

Fondant icing dates from the Victorian era and is more commonly prepared by professional bakers rather than home cooks. See fondant. A boiled syrup of sugar and glucose is cooled and kneaded on a cold surface until it becomes stiff and creamy. When required as icing, a piece of the sugar paste is softened with hot water until it reaches a pouring consistency.

The appeal of novelty cakes has led to the introduction of ready-prepared, colored sugar-paste icing that is rolled into sheets for draping over a cake before decorating. Small figures, animals, or other models for placing on the cake are made from the same mixture. The ease of using bought sugar-paste has spawned a thriving interest in cake decoration, and special decorating equipment, such as miniature pump-action sprays of food colors, have been developed for use with patterns and stencils—all intended to assist creativity. See cake decoration.

See also dolly varden cake; publications, trade; and servers, sugar.

Imperial Sugar Company, a major American sugar producer, was established in 1905 by Isaac H. Kempner (and other family members) and William T. Eldridge in what is today Sugar Land, Texas, a small community about 25 miles southwest of Houston.

Sugarcane had been grown in the area since the 1830s, when settlers found that the soil and climate, especially along the Brazos River, were conducive to its cultivation. See sugarcane and sugarcane agriculture. Samuel M. Williams and his brother grew sugarcane on their plantation on Oyster Creek, and in 1843 they produced enough to warrant construction of a small sugar mill on their property. This mill refined small quantities of sugar and also produced blackstrap molasses. See molasses. Ed Cunningham subsequently acquired the Williams property and built a much larger refinery; in 1905 Isaac H. Kempner acquired the property in turn, naming his business the “Imperial” Sugar Company and expanding and diversifying its operations into areas unrelated to sugar refining. He even opened a bank. Kempner also built houses and stores for his workers in the company-owned town, which he named Sugar Land. The Imperial Sugar Company was incorporated in 1907, two years after its founding.

As sugar consumption increased in the United States during the first decade of the twentieth century, so did sugar production, and with the start of World War I in 1914 production increased further to supply European nations at war. When the United States entered the war in 1917 the demand for sugar outstripped supply, so the Imperial Sugar Company imported raw sugar from the Caribbean in order to operate its refineries year-round.

The 1920s were years of change. The Imperial Sugar Company warded off efforts by Domino Sugar (then known as the American Sugar Refining Company) to control sugar production and distribution in the United States, and also held its own against the Texas Sugar Refining Company, which collapsed during the Depression. Imperial Sugar itself barely survived the Depression and did so only with a federal loan from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. During the 1930s, the company innovated the packing of sugar in cotton bags, which were more convenient and sanitary than sugar scooped from barrels in stores. The company stopped growing sugarcane in Sugar Land in 1928 but continued to process raw sugar at its refinery in the city until 2003. See sugar refineries.

After World War II the company expanded, producing more than 2 million pounds of sugar daily. The raw sugar came from the Dominican Republic, Brazil, Australia, and other countries. Imperial sold bulk sugar to candy manufacturers, bottlers, and other companies, and its products successfully competed against corn syrup and other cane sugar substitutes. See corn syrup.

In 1988 the company merged with the Holly Sugar Corporation, a beet sugar refinery headquartered in Colorado Springs, and became the Imperial Holly Sugar Corporation. In 1996 it added the Spreckels Sugar Company of California and other companies, and Imperial Holly became one of the nation’s largest refiners and distributors of sugar. Although Imperial Holly Corporation filed for bankruptcy in January 2001, the company survived; it closed its Sugar Land refinery in May 2003 but maintained refinery operations in California, Georgia, and Louisiana.

The current types of sugar marketed by Imperial Sugar are free-flowing sugar; granulated sugar; sugar shakers; light brown sugar; dark brown sugar; Stevia; and powdered sugar. See sugar. These products are sold under a variety of brand names, including Dixie Crystals, Imperial, Savannah Gold, NatureWise, and Holly, as well as private labels. The company also markets organic and fair-trade sweeteners and sweetener blends through partnerships, such as Natural Sweet Ventures, formed in 2010 with Pure Circle Limited to develop and commercialize Stevia sweetener blends; Louisiana Sugar Refining, formed in 2009 as a three-party joint venture with Sugar Growers and Refiners Inc. and Cargill Inc. to build and operate a cane sugar refinery in Gramercy, Louisiana; Comercializadora Santos Imperial together with Ingenios Santos, which markets sugar products in Mexico and the United States; and Wholesome Sweeteners, which sells organic, fair-trade, and other natural sweeteners such as agave syrup, honey, and Stevia. See agave nectar and stevia. The Imperial Sugar Company also sells refined sugar, molasses, and other ingredients to industrial customers, principally food manufacturers, for use in candy, baked goods, frozen desserts, cereal, dairy products, canned goods, and beverages.

Imperial Sugar has changed hands many times, most recently in 2012, when it became a wholly owned subsidiary of Louis Dreyfus Commodities LLC, which combined its sugar holdings in Brazil and other places to create Ld Commodities Sugar Holdings, headquartered in Wilton, Connecticut.

See also american sugar refining company; havemeyer, henry osborne; plantations, sugar; sugar refining; and sugar trade.

India is the second most populous country in the world after China and the seventh largest in area. No other country has such a diversity of climates and soils, races and languages, religions and sects, tribes, castes and classes, customs—and cuisines. Sometimes India is compared with Europe in its multitude of languages and ethnic groups—but imagine a Europe with eight religions (four of them born on Indian soil), each with its own dietary prohibitions and restrictions. This cultural diversity is reflected in the number and variety of sweets and sweet dishes.

Probably in no other part of the world are sweets (mithai in Hindi) so varied, so numerous, or so invested with meaning. See mithai. Sweets are an essential component of hospitality and celebration: Indians send sweets to friends and family as gifts and consume them to celebrate passing an examination or getting a new job. They mark rites of passage, such as the birth of a child, pregnancy, marriage, even death. In the Hindu classification of foods by qualities, sugar, milk, and ghee, all ingredients in sweets, are considered sattvic—a Sanskrit term meaning “pure,” “conducive to lucidity and calmness”—and can be eaten by everyone, even spiritual leaders and the most orthodox vegetarians. Sweets are also considered ritually pure and are offered to the gods and distributed to the devotees at Hindu temples. Sweets are sometimes eaten during fasts or used to break a fast.

Muslims also celebrate holidays and important religious occasions with sweets. For example, at the end of Ramadan, the fasting month, they prepare khorma (khurma), a thick pudding made of sautéed vermicelli, thickened milk, sugar, dates, and sometimes nuts, raisins, rosewater, and saffron for breakfast. See ramadan. India’s Christians celebrate Christmas with delicious fruitcakes, while India’s Parsi community (descendants of Persian Zoroastrians) enjoys dishes that reflect European, Iranian, and Indian influences, such as mava malido, an egg and semolina pudding, or koomas, a spiced baked cake.

Everyday Indian meals do not usually end with a dessert, except perhaps fruit or yogurt, sometimes sweetened. Instead, sweets and savory items are part of the late afternoon meal called tea or tiffin. Some sweets are made at home, but many are purchased from professional sweet makers, known as halwai or moira in Hindi. The process of making some sweets can be extremely lengthy and labor-intensive.

Unfortunately, the sweets served in Indian restaurants in the West—typically, kulfi, carrot halvah, ras malai, gulab jamun, and kheer—offer a limited introduction to the wonderful diversity and subtlety of Indian sweet dishes. A greater variety can be found in Indian sweetshops in large North American cities.

Historical Background

The earliest Indian sweet dishes were flavored with honey, dates, and fruits. The first sweet mentioned in the Sanskrit literature around 1000 b.c.e. is apupa, a round cake made of barley or rice flour baked in ghee and sweetened with honey. There are also references to ksira, milk and boiled rice, the ancestor of modern rice puddings.

Sugarcane grew in India from ancient times. Originally it was chewed, but during the first millennium b.c.e. Indians began to convert it to various products. The stems were crushed in a machine called a yantra, a large mortar and pestle turned by oxen that is still used in rural areas. The extracted juice, which contains up to 17 percent sucrose, was filtered and cooked slowly in a large metal pot fueled by the cane stalks. The thickened juice, called phanita, was similar to molasses and further concentrated and dried to make solid pieces of brown sugar, known as jaggery or gur. (The English word “sugar” comes from sarkara, the Sanskrit word for jaggery.) In the third century b.c.e., Indians discovered the technique of refining the juice into crystals, called khand (the origin of the English word “candy”). The Greek ambassador and writer Megasthenes (ca. 350–290 b.c.e.) was amazed by the sight of “tall reeds which are sweet both by nature and by concoction”—sugarcane, not known in Europe at the time—and “stones the colour of frankincense, sweeter than figs or honey.” See sugarcane agriculture and sugar refining.

Later technological refinements, perhaps from Persia or Egypt, produced pure white loaves of sugar. The discovery that sugarcane could grow in the New World resulted in a decline in the Indian sugar industry, and by the nineteenth century sugar was imported from China and elsewhere. (Even today white sugar is called chini in Bengali and Hindi.) In 1912 the Sugarcane Research Institute developed hybrid sugarcanes using New World plants. Production increased dramatically, and today India is the world’s second largest producer after Brazil. Indians are also the world’s largest consumers of sugar, consuming 60 percent more than China’s comparable population; middle-class Indians consume more sugar per capita than Americans.

Another source of sugar is the juice of palm trees, whose distinctive flavor makes it the preferred flavoring for certain sweets, especially in the winter. See palm sugar.

In Ayurveda, the Indian system of medicine, dishes made from sugar were believed to have restorative powers and cooling properties. Even today, some sweet makers produce items containing ayurvedic herbs, such as salan pak, a Gujarati sweet made in the winter. It contains over 30 ingredients, including cloves, pepper, cinnamon, nutmeg, almonds, pistachios, Indian ginseng, and a whole host of ayurvedic herbs. Salan pak has a wonderfully complex, piquant flavor but can only be eaten in small amounts because of its powerful medicinal effects.

Ingredients

The word “sweet” encompasses a wide range of dishes, shown in the table below. After sugar, the most common ingredient is cow or buffalo milk. Milk has been an integral part of the Indian diet from ancient times. Cows have traditionally held a special place in Indian society, revered as the “eternal mother” for their usefulness as a source of labor and nourishment (excluding meat). Buffalo milk (from bos bubalus, a native species) has double the fat content of cow milk and is preferred by some sweet aficionados. See milk.

An important component of sweets is khoa (khoya), a semi-solid or solid product made by slowly boiling milk until it thickens into a solid, constantly stirring to prevent caramelization. The ratio of milk solids to milk can range from 1:6 to 1:4. Before use it is often pulverized and sifted. Chhana, or curds, is made by bringing milk to a boil, then adding a souring agent, such as citric acid or old whey. This is done either while the milk is being heated, which makes a firmer product, or after it is removed from the stove. The curds are drained through a thin cloth and should be used immediately. Pressing the drained chhana under a weight to remove more moisture yields paneer, an ingredient often used in North Indian vegetarian dishes. Other common ingredients are chickpeas and lentils; rice, wheat, and other grains; fruits; vegetables; nuts (especially almonds, cashews, and pistachios); seeds (especially sesame seeds); and raisins. Clarified butter (ghee) is a preferred cooking medium. Popular flavorings include rose or kewra (screwpine) water, and spices, especially cardamom. See flower waters; pandanus; and spices. Coloring agents include saffron, cochineal (red), and turmeric. Most sweets are subjected to some form of heat treatment that enables them to be preserved.

Some Categories of Indian Sweets

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Hard or semi-hard, dry | Halvah, barfi, laddu, peda, modaka, sandesh |

| In a liquid or syrup | Ras gulla, jalebi, ledikeni, gulab jamun, ras malai |

| Puddings | Payesh, payasam, pongal, kheer |

| Crepes | Pantua, malpoa |

| Yogurt | Shrikhand, misthi doi |

| European | Bibinca, fruit cake, biscuits |

| Crunchy | Chikki (peanut brittle), gur papdi |

Varieties of Sweets

Some sweets are eaten everywhere in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh; others are specialties of a region, city, even a single village. Some are variants of those found over an area extending from Turkey through the Middle East, and Central Asia to India, such as falooda, halvah, and jalebi. An entire encyclopedia could be devoted to Indian sweets; here, we have room only to list the main ones. Universally popular sweets include barfi, laddus, jalebi, halvah, and a rice pudding known variously as payesh, payasam, or kheer. See barfi; laddu; halvah; payasam; and zalabiya.

A popular street food, jalebis (jalibis) resemble large pretzels. A thin batter of chickpea, urad dal, or white flour, sometimes mixed with a little yogurt, is extruded into hot oil to form large spirals that are soaked in warm sugar syrup for a few minutes. In northern India jalebis are enjoyed for breakfast, often with puris (puffed wheat bread) and halvah. A variation is imarti, which has a flower-like shape.

Unlike Middle Eastern halvah, usually made from sesame seeds, Indian halvah comes in two basic varieties: one made from semolina cooked with jaggery, clarified butter, and sometimes nuts and raisins, the other from vegetables (especially carrots and bottle squash), lentils, nuts, or sometimes khoa. Both versions require a lot of clarified butter and are moister and flakier than Middle Eastern halvah. Karachi halvah is a bright orange, somewhat rubbery, translucent halvah made from cornstarch, nuts, and ghee.

Kulfi, the Indian version of ice cream, is sweetened khoa frozen in cone-shaped molds. Unlike ice cream, the mixture is not churned, and the consistency is denser. Typical flavors include mango, pistachio, orange, rose, and saffron. Commercial kulfi may be frozen onto a stick for easy eating. It is often served with falooda, thin rice noodles scented with rosewater. Sohan papdi or patisa is a dry, very flaky dish made of chickpea flour, white flour, sugar, and a lot of ghee. It is often topped with charmagaz, a blend of almonds and pumpkin, cantaloupe, and watermelon seeds.

Rice pudding is a favorite throughout the subcontinent. Kheer, called payesh in Bengali, is made by slowly cooking rice and milk until the mixture thickens, then including sugar and flavoring it with kewra water. Almonds, raisins, and pistachios can be added. South Indians prepare a version called payasam. Zarda is a dish enjoyed by Muslims during religious festivals, such as Musharram and ʿId al-Fiṭr. Long-grain rice is cooked with sugar and aromatic spices, such as cardamom, cloves, and cinnamon, and sautéed in clarified butter. On special occasions, these and other sweet dishes are decorated with edible silver foil, called vark. See leaf, gold and silver.

Northern India

The main ingredient in Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, New Delhi, and other parts of northern India is khoa. It is a key ingredient in barfi and pedha, a round sweet flavored with chopped nuts and cardamom associated with the cities of Varanasi and Mathura. Petha, a famous dish of Agra, is a cross between fudge and preserves. Ash gourds are soaked in lime (calcium carbonate), boiled in alum powder and water, and then cooked again in sugar syrup. The result is a lovely, pale green, subtly flavored delicacy.

Rabri is thickened milk mixed with chopped nuts and the skin formed on the milk during cooking. Firni is a kind of custard made of rice flour or cornstarch cooked in milk with sugar, nuts, cardamom powder, and rosewater or kewra water. Gulab jamun are brown balls of khoa and flour that are fried and then soaked in sugar syrup.

Desserts do not play as large a role in the cuisine of the northernmost state of Kashmir as in other parts of India. The most popular include akhor barfi made from local walnuts; firun/firni, a custard made from ground rice, sugar, milk, saffron (which is native to Kashmir), and nuts and set in traditional earthenware pots; and zarda, a sweetened rice pulao prepared with nuts, saffron, and aromatic spices. The last two dishes are often served during ʿId al-Fiṭr and other Muslim celebrations.

Western India

In parts of western India, sweets are eaten during the meal itself, and often a pinch of sugar is added to vegetarian dishes. Laddus, especially churma laddu—deep-fried balls made from wheat flour and nuts—are popular. The Surat region of Gujarat is well known for the expertise of its sweet makers. A famous Surati sweet is ghari, a puri (circular wheat bread) with a sweet filling of khoa and nuts. It even has its own festival—Chandani Padva. Another famous Surati sweet is halwason—hard squares made from broken wheat, khoa, nutmeg, and nuts. Mohanthal is a kind of barfi made from chickpea flour, ghee, sugar, almonds, saffron, and pistachios. One of the most elaborate sweets is sukhan feni—very fine strands of sweet, flaky dough garnished with pistachios.

A traditional Maharashtrian sweet is puran poli, wheat pancakes filled with lentils and sugar, and served with hot milk or ghee. An emblematic (and very ancient) dish of Gujarat and Maharashtra is shrikhand—drained yogurt mixed with sugar, saffron, and cardamom and sometimes garnished with chopped nuts. Its unique sweet and sour taste makes it beloved by some and disliked by others.

The tiny state of Goa was part of the Portuguese empire for 400 years, and Portuguese influence is evident in the language and cuisine, especially the wide array of European-style cakes and pastries. See portugal’s influence in asia. Bibinca (bebinca) is a many-layered baked pudding made of egg yolks, sugar, flour, and coconut milk, and garnished with nuts. Baath is a cake made from semolina, eggs, ghee, coconuts, sugar, and caraway seeds.

Southern India

The most emblematic South Indian sweet dish is payasam, a pudding of rice and milk or coconut milk, sometimes with dal, fruit, raisins, and nuts. It often has a pinkish color because of the long cooking time that caramelizes the milk. In Kerala, the king of payasams served at festive occasions is ada pradaman, made from a special pressed rice, coconut milk, jaggery, coconut milk, coconut flakes, ghee, cardamom, cashews, and raisins.

In Tamil Nadu, a favorite sweet is pal payasam—small puris dipped in sweetened kheer and served hot or cold. The most important festival is Pongal, which is also the name of the dish served at this time: a mixture of boiled rice, dal, milk, jaggery, ghee, nuts, raisins, and coconut.

The city of Hyderabad, once home to the court of the Nizams, has a rich culinary and sweet culture influenced by Persian cuisine. Double Ka meetha (also known as shahi tukra) is a bread pudding (and probably an adaptation of English trifle) made from Western-style bread, khoa, saffron, and spices sautéed in ghee, soaked in milk, covered with sugar syrup, and baked. Vermicelli (seviyan in Hindi and Urdu) are very thin wheat noodles used in many dishes, including reshmi zulfein, made with lotus seeds and nuts, and sevia ka muzaffar, vermicelli with fried cardamom pods, thickened milk, and dried coconut. Khubani ka meetha is a very popular local dish made of cooked sweetened apricots topped with cream.

Eastern India

Bengalis—inhabitants of the Indian state of West Bengal and the Republic of Bangladesh—are famous for their love of mishti, or sweets, considered the apogee of the Indian sweet maker’s art. Most commercial sweets are made from chhana; khoa is used mainly as a secondary ingredient. Chhana’s popularity in Bengal may have come from the Portuguese who lived in the region in the seventeenth century and specialized in the preparation of sweetmeats, breads, and cheese. The French traveler François Bernier wrote in 1659: “Bengal is celebrated for its sweetmeats, especially in places inhabited by the Portuguese, who are skilful in the art of preparing them and with whom they are an article of considerable trade.”

The extensive use of chhana by professional sweet makers began in the mid-nineteenth century when B. C. Nag, N. C. Das, and other Calcutta sweetshop owners expanded their repertoire by inventing new varieties of sweets to serve an affluent and growing urban middle class. See kolkata. The most famous sweets are rosogolla, a light spongy white ball of chhana served in sugar syrup; rajbhog, a giant rosogolla; a dark-colored fried version called ledikeni; cham cham, small patties dipped in thickened milk and sprinkled with grated khoa; ras malai, khoa and sugar balls floating in cardamom-flavored cream; and pantua, sausage-shaped spheres fried to a golden brown and dropped in sugar syrup. See ledikeni and rosogolla. The apogee of the Bengali sweet makers’ art is sandesh, small sweetmeats made from chhana and sugar, fried in clarified butter, and pressed into pretty molds shaped like flowers, fruit, or shells. See sandesh.

Sweets generally made at home include patishapta, a semolina pancake filled with sugar, coconut, and khoa; pithes, coconut balls or disks coated in batter, deep-fried, and served in sugar syrup; and malpoa, patties made of yogurt, flour, and sugar, fried until golden brown, then dipped briefly in sugar syrup. Misthi dol or lal doi, yogurt sweetened with sugar, are standard ends to a Bengali meal.

See also coconut; diwali; hinduism; islam; persia; south asia; sugar; and sugarcane.

insects, or at least traces of them, show up in just about every edible substance—even in something as innocent as candy. However, insects are sometimes intentionally made into candies in order to “gross out” the squeamish, or to demonstrate the eater’s machismo. In the United States such candies have typically been little more than novelty items, such as the chocolate-covered ants introduced by Reese Finer Foods in the 1950s. Thanks to Groucho Marx, who quipped to Reese executive Morris H. Kushner that “I can’t eat your chocolate-covered ants … the chocolate upsets my stomach,” these treats became as much punch line as actual snack. Other consumers proved to have sturdier digestions. In 1956 the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal reported that Americans were developing a taste for exotic imported foods—and both chose chocolate-covered ants as the most newsworthy example.

Since then, the market for candy-encrusted bugs has proliferated. HOTLIX—a candy company in Grover Beach, California—is famous (or infamous) for its lines of creepy crawly confections. The company claims that its “owner found inspiration from the tequila with a worm.” Whatever the origins, HOTLIX now produces and sells a wide range of products: Cricket Lick-It Suckers (blueberry, grape, orange, and strawberry lollipops, each with a crisply fried cricket inside); Ant Candy with Real Farm Ants (disks of white and milk chocolate, studded with crunchy ants); and InsectNside Scorpion Brittle (a toffee-flavored slab of “amber” containing an actual scorpion). The company also offers a line of savory insect snacks. For a more grown-up taste, its Tequila Lollipops claim to feature real earthworms. A purist might demand un gusano, a maguey larva (Hypopta agavis) from the agave plant used to make mescal, but here the critter is more likely just another mealworm. Other insect confectioners produce such items as Butterfly Candy (a slab of strawberry-flavored hard candy enclosing a Bougainvillea blossom and a mealworm pupa), Milk Chocolate–Covered Crickets, and Watermelon Lollipops with mealworms inside.

Sometimes the insects are not in the sweets; they make the sweets. Bees, which convert nectar to honey, are the best-known example, but they are not the only ones. A group of insects called Psillids (including aphids and scale insects) collect sugar-rich sap from plants and turn it into honeydew. This honeydew can be collected by humans directly from leaves, or harvested by ants. The strong flavors of honeydews—le miel de forêt, Honigtauhonig, or miele di bosco—are distinctly different, varying according to the plant species from which the nectar is collected. It is used just as honey, either eaten directly, or as an ingredient in baking. Because some species of ants collect more honeydew than they need for immediate use, they have evolved a unique storage system. Honeypot ants (Myrmecocystus genus) feed the excess to certain specialized ants (called “repletes”) that never leave their underground colonies. The repletes’ gasters—the last section of their abdomens—swell to enormous size as they are filled with sweet syrup. These “sugar bags” are transparent, jewel-like spheres, between the size of a chickpea and a small grape. In semi-arid regions of Africa, Australia, and North and South America, people dig for these delicious repletes. Vic Cherikoff, who runs an Australian firm called Bush Tucker Party Ltd., prepares a special dessert named Honey Ant Dreaming. The recipe calls for filling small chocolate cups one-third full with sugar-bag honey, spooning on whipped cream, and then garnishing the top with a frozen honeypot replete.

Even if most Americans do not choose bugs as a special treat, they may still be eating them—and not just in the small, accidental amounts that government sanitary rules permit. “Confectioner’s glaze,” a more appealing name for shellac, gives some candies their appetizing shine. Less appetizing, however, is the fact that it is produced from a secretion made by female Lac Bugs (scale insects of the Kerria genus). These secretions are also used to make a red dye. More common is cochineal, a carmine coloring used in many candies, made from the dried bodies of another type of scale insect (Dactylopius genus). Cochineal was a very popular dye before aniline dyes, made from coal tar, were discovered in the nineteenth century. One might imagine that most people would prefer artificial food coloring from a nice clean laboratory to a natural one made from bugs that are farmed and scraped off of cactuses—but that is not the case. Cochineal is now more popular than ever. See food colorings.

In fact, bug confectionery seems to be experiencing a renaissance, at least according to a 2013 report by the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (van Huis et al.). “Fried insects embedded in chocolate or hard candy, and fried and seasoned larvae,” the FAO writes, “can be found in the United States, while the world’s most famous luxury stores, Harrods and Selfridges, sell fancy insect products in London.” What would Groucho have to say?

See persia.

Islam, the religion practiced by more than 1.5 billion followers of Prophet Muhammad around the world, reserves a special, even privileged, status for sweets. Dates and honey, in particular, remained primary even after sugarcane plantations and cane sugar refining spread throughout the Islamic world beginning in the seventh century.

Dates and honey have been valuable commodities since antiquity, not just as sweet foodstuffs but also for their medicinal properties. However, their high standing among Arabs was firmly established with the advent of Islam. The date palm was repeatedly mentioned in the holy Qurʾān as God’s gift to His believers, and in the verses on the birth of Jesus, Mary was asked to shake the date palm in order to feed herself with the dates falling from the tree. The Prophet himself endorsed the date by saying that seven dates a day will keep poison and witchcraft away. His favorite was the Medina date variety ʿajwa, described as the food of heaven and used to help wean children. See dates. Following the tradition of the Prophet, in some Muslim countries today, newborns are given a taste of dates or honey, in a ceremony called taḥnīk, and lactating mothers are fed a lot of dates. Modern medicine has shown that dates do indeed activate milk hormones and that they act as tonic for uterine muscles, which stimulate delivery contractions.

In the Qurʾān, Muslim believers are promised rivers of purified honey, and in another verse, honey itself is described as a healer for mankind. See honey. It is often praised as God’s sweet medicine, unlike physicians’ bitter medicines. From the early-fourteenth-century Traditional Medicine of the Prophet, known as Ṭibb al-Nabī, we know that the Prophet was partial to honey as food and repeatedly recommended it as medicine, especially for stomach and chest ailments. He is said to have enjoyed his first taste of the luxurious condensed pudding faludhaj, made of wheat starch, butter, and honey. Even after honey was often replaced in medieval times by cane sugar in making sweetmeats and pastries, it remained highly valued, especially in home cures like electuaries, pastes, and jams. Honey helped preserve the curative properties of the spices and herbs they contained and made them taste so palatable that many ended up being consumed for sheer pleasure.

Regardless of the type of sweetener used, since medieval times the eating of sweet foods has been generally approved of in the Islamic world. Following the ancient Galenic humoral theories of medicine embraced during medieval times, desserts and sweet drinks were usually offered at the end of the meal. Their hot and moist properties were believed to aid digestion, which was metaphorically described in terms of cooking. Also because of these properties, sweets were thought of as male sexual enhancers, a medicinal lore that still lingers today in some parts of the Muslim world. Today’s groom, for instance, would be advised to eat at least 1 pound of dates on his wedding day.

The significance of sweets in Islamic religious and social rituals is manifested in the myriad varieties and abundant quantities consumed. Among these are the syrupy pastries enjoyed during the fasting month of Ramadan and the huge number of stuffed cookies like kleicha and maʾmoul baked especially for the two major feasts of ʿId al-Fiṭr (celebrating the end of Ramadan) and ʿId al-Aḍḥā (rejoicing over the performance of Hajj in Mecca). See ramadan. The Prophet’s birthday, Mawlid al-Nabī, is a significantly sweet celebration, especially in Egypt, where decorated dolls of sugar and nuts are given to children. On other less joyous religious occasions, such as ʿĀshūrāʾ, the tenth day of the sacred month of Muḥarram, a sweet wheat porridge called harīsa is made and distributed, especially by Shiites mourning the death of Imam Ḥusayn, the Prophet’s grandson. In Iran, this sad event is commemorated with the yellow rice pudding zerde, a dessert that in Turkey presides over occasions like wedding feasts.

The souls of dead Muslims have associations with sweets as well: after burial rites, date sweetmeats and starch-based puddings, cookies, and pastries are distributed to the poor. The same happens when the graves of family members are visited on religious feast days. Other Muslim rites of passage, such as circumcision and weddings, are closely associated with rich desserts like baklava. See baklava. Toffees and sugar-coated almonds are joyfully thrown by handfuls at the guests to the accompaniment of loud ululations. See confetti. Immediately after a boy’s circumcision, a piece of candy was traditionally popped into his mouth so that he would forget the pain.

A modern challenge caused by globalization and the rise of Muslim immigrants worldwide is halal dessert. Like halal meat for observant Muslims, desserts need to conform to Islamic law. No dessert may contain alcohol; therefore, powdered pure vanilla is substituted for vanilla extract, and gelatin must come from sources other than pigs, such as cows or fish, or any animal slaughtered ritually. Major stores have increasingly started to accommodate halal desserts. At the British department store Harrods, for instance, Belgian alcohol-free chocolate and sugar-coated dried fruits using halal gelatin are available for Muslims to purchase.

See also fruit pastes; fruit preserves; funerals; medicinal uses of sugar; palm sugar; and wedding.

isomalt is a polyol, or sugar alcohol. It is a colorless, odorless hydrogenated disaccharide that is used as a sugar substitute to replace sucrose, glucose, corn syrup, fructose, and the like in foods and drinks. Isomalt was discovered and developed in 1957 by scientists at the German company Südzuker AG, the largest sugar producer in Europe. The trademarked names for isomalt, Palatinose and Palatinit are derived from the Palatinate (Pfaltz) region of Germany, where isomalt was developed.

Isomalt has several advantages. It has properties similar to sucrose but half the calories, making it useful for lower-calorie foods. It has no aftertaste and a longer shelf-life than sucrose. Consuming isomalt does not substantially increase glucose levels in the bloodstream, so it is suitable for diabetics. Isomalt does not promote tooth decay, and products containing isomalt can be labeled “sugar free.” See dental caries. Although the excessive consumption of isomalt can cause diarrhea and gastric problems, it is approved for use as a food additive in most countries.

Isomalt is mainly used in baked goods—cereal, cereal bars, sponge cake, cookies, and biscuits—in hard candies, toffees, chocolates, and chewing gums, and in pharmaceuticals, such as throat lozenges and cough drops. It is also used for making decorative sugar sculptures, such as cast sugar (sucre coulé), as it does not crystallize as quickly as sucrose and can be heated without clouding. See sugar sculpture.

See also corn syrup; fructose; and glucose.

Istanbul is Turkey’s largest city, known in antiquity as Byzantium and from the fourth century until the Turkish conquest in 1453 as Constantinople. The city was first settled around 6500 b.c.e., and it was through the surrounding region that agriculture spread from the Near East into Europe the following millenium. Istanbul owes its importance to a strategic location between Europe and Asia on a major shipping route through the Bosphorus Strait, which links the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. For nearly 2,000 years it was the capital of three successive empires: first the Roman (330–395 c.e.), then the Byzantine (395–1453 c.e.), and finally the Ottoman (1453–1922 c.e.), and so it has long been a cosmopolitan city inhabited by people of different faiths and diverse origins, as well as a center of international trade. Consequently, Istanbul has been the hub of three imperial cuisines that made use of both local and imported foodstuffs, ranging from caviar from the north coast of the Black Sea to spices from India.

In the early fourteenth century, during the Byzantine period, sugar of various types, as well as sugar candy and comfits “of every kind,” arrived from Egypt, Damascus, Cyprus, and Rhodes and were traded in the city. After the Ottoman Turks conquered Istanbul in 1453, sugar was consumed in ever-greater quantities, and in the sixteenth century the Turkish scholar Mustafa Ali of Gallipoli likened the sugar of Egypt to “a sea flowing ultimately to Istanbul.” The medieval Arab legacy of sweetmeats and sweet pastries was inherited and further developed by Turkish cuisine, a process that centered on the palace and Istanbul’s elite ruling class. In this innovative cuisine, earlier Arab puddings such as maʾmūniyya (Turkish memuniye) made of chicken breast, rice, and almond milk were eventually transformed into deep-fried balls of rice helva sprinkled with sugar, nuts, and rosewater. Similarly, kataif, in its original Arab form a crumpet soaked in syrup, evolved into fine threads of cooked batter also known as kataif. Most of the innovations in Turkish confectionery emerged in Istanbul between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries. Among these were boiled sweets known as akide, lokum (Turkish Delight), kazandibi (a type of caramelized milk pudding), ekmek kadayıf (syrup-soaked rusk eaten with clotted cream), and three confectionery items that evolved from sweetened medical preparations: şerbet şekeri (sherbet sugar), a soft toffee known as macun, and çevirme. See lokum and spoon sweet.

In the nineteenth century Europeans curious about “Oriental confectionery” looked to Istanbul. Perhaps the most prominent was Friedrich Unger, royal confectioner at the court of the first Greek king, Otto I (a Bavarian prince by birth). Unger left a detailed record of his research in Conditorei des Orients (1838), writing that in Istanbul he finally satisfied his “hunger for learning.”