gag candy encompasses the candies with extreme flavors, funny names, unexpected ingredients, and surprising shapes that most children love. Some unusual candies, such as wax lips, were first manufactured in the nineteenth century. During the 1920s, the novelty candy trade offered chocolate-covered onions and cheese, and sweet pipes with tobacco made of little flakes of licorice.

A related genre was candy cigarettes made from chocolate or bubble gum (both wrapped in white paper), or from a chalky-tasting mixture of sugar and cornstarch. White with a pink tip, the latter looked something like real cigarettes. Some brands were made to exude a puff of powdery sugar if you blew into them, in imitation of smoke. Candy was packed into cellophane-wrapped, cigarette-sized packages emblazoned with real tobacco brands, such as Camel, Marlboro, and Chesterfield, but some companies used names that were merely evocative of the real thing, such as Lucky Star and Roundup, rather than actual brand names. In the 1960s, as concern about the health effects of cigarette smoking emerged, so did the fear that these candies might encourage children to smoke later in life. In response, some manufacturers altered their products. The word “cigarette” disappeared, and the products were renamed “candy sticks” or “stix.” Efforts to ban the sale and manufacture of candy cigarettes failed in the United States, although other countries have banned them.

During the 1950s, large numbers of American children began celebrating Halloween by going door to door “trick or treating” for candy. See halloween. Many gag candies were created to tap into the massive sales of candy around this holiday. Ferrara Pan Candy Company, a Chicago firm, already included Boston Baked Beans (candy-coated peanuts) and cinnamon-flavored Redhots in its product line; in 1954 it added the hotter-still jawbreaker-size Atomic Fireballs and in 1962 introduced very sour lemon drops. Just Born, makers of Peeps, created Hot Tamales, which look nothing like tamales but have a hot cinnamon flavor. See peeps. Special gag candies have been developed for other holidays as well. For Easter, there is a realistic-looking egg that bounces, and for a Christmas stocking stuffer, coal candy made from hard licorice is sold in a miniature coal scuttle with a tiny hammer for breaking it up.

Gag candies have also been associated with children’s movies. Breaker Confections, a Chicago candy company, bought the rights to the Willy Wonka name from the 1971 musical film Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory and produced a series of candies, including “Everlasting Gobstoppers,” mentioned in the movie. The company was eventually acquired by Nestlé, which began producing Wonka Bars in 1998. Sales were not strong, so Nestlé decided to discontinue the line. But in 2000, when director Tim Burton announced plans to remake the film, Nestlé jumped at the chance for product placement in the movie, providing hundreds of candy bars and thousands of props, and engaged in a massive promotional campaign for both the movie and the candy. The new movie was a tremendous success when it was released in 2005, as were the Nestlé candies featuring a cartoon likeness of Willy Wonka.

Certain gag candies cause unusual effects. Bloody Mouth Candy, for instance, is a hard candy that tints the eater’s saliva blood red when chewed. Other candies produce black, blue, or green colors. Still other candies have shockingly unexpected flavors and sensations, such as garlicky, mustardy, fishy, soapy, or salty flavors. Three unusual candies were hallmarks of the 1970s. General Foods released Pop Rocks in 1975, a hard candy with air pockets that contained carbonation, causing a crackling sensation when they melted in the mouth. Rumor had it that Pop Rocks exploded in the stomach, leading the company to discontinue the candy. Other unusual candies of the era included Zotz, a very tart hard candy that fizzed in the mouth, and orange and strawberry Space Dust, another crackling candy.

Vials and bottles filled with candy pills, often included in toy “Doctor” and “Nurse” kits, have been around for decades. This vial was designed by studio m for the candy store Happy Pills in Barcelona, Spain. © happy pills

Vials and bottles filled with candy pills, often included in toy “doctor” and “nurse” kits, have been around for decades. As was the case with candy cigarettes, some authorities warned that children would confuse actual medication with candy, with potentially harmful or even lethal consequences. Nonetheless, candy pills remain on the market, updated with humorous labels such as “Madvil,” “Damitol,” and “Chill Pills.”

In the 1980s manufacturers began to produce “gross-out” candy, such as Chocolate Snotty Noses, Dinosaur Dollops, White Chocolate Maggots, and Ear Wax Candy. Gelatin-based gummi candy lends itself to molding in all sorts of shapes and colors, and gummi worms are a perennial favorite. See gummies and haribo. The realistic brown Gummy Earthworms have delighted children—and surprised fishermen. The NECCO candy company offers strongly flavored gummies in the shape of feet—Sour Stinky Feet and Hot Stinky Feet. See necco. Others have produced “erotic” sweets with anatomically explicit shapes.

All these candies pale before the myriad gross-out candies of the twenty-first century. In 2001 the Jelly Belly Candy Company released Bertie Bott’s Every Flavour Beans in association with J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books and movies. Flavors include Rotten Egg, Vomit, and Earthworm. The Danish candy company Dracco sells candy-pooping dogs, scorpion lollipops, and candy tongue tattoos. Fear Factor candy, based on the television series, includes crunchy worm larvae, slimy octopi, and frogs’ legs served with a blood-red candy sauce. According to manufacturers, gross-out candy is one the fastest-growing segments of the candy market.

See also candy; children’s candy; chewing gum; extreme candy; and penny candy.

galette is a flat, round cake made with pastry dough (short crust or puff pastry) and sometimes filled with rich frangipane. See frangipane. There are many kinds of galette, the most famous being the galette des rois (king cake) that dates at least to the Middle Ages. The galette des rois that is traditionally served on Epiphany contains a hidden bean or porcelain figure. The guest who gets the slice of cake with the bean is the “king” of the day or the feast. P. J. B. Le Grand d’Aussy writes in Histoire de la vie privée des Français (1782) that the galette des rois (also called a gâteau à fève, bean cake) was served on any joyous occasion, such as a baptism. He also writes that hot galettes were sold in the streets, and that “galette chaudes” was one of the famed street cries of Paris in the thirteenth century.

A galette can be a simple snack, as in the beloved children’s story “Roule Galette,” in which an old lady sweeps up bits of grain left in the granary to make a cake for her husband. In some areas of France, particularly in the South, a galette is made of brioche and flavored with lemon zest. In Normandy, galettes are made with puff pastry and are filled with fruit jam and crème fraîche. In France and French Canada, galette can also designate a cookie made from pastry dough covered in sugar and baked; in Brittany, the term designates a savory, filled buckwheat crêpe. In his nineteenth-century Dictionnaire universel de cuisine pratique (1894–1906), Joseph Favre laments that the galette is a heavy and indigestible cake, which suggests that the pastry chef’s art of galette making has improved since Favre’s time.

See also children’s literature; france; pastry, puff; and twelfth night cake.

gastris, an ancient Greek sweetmeat of the second century b.c.e. and a regional specialty of Crete, is important not just intrinsically but as a window into a lost world. Hardly any instructions for making sweets survive from classical Greece. The recipe is known because it happens to be quoted in the Deipnosophists of Athenaeus (book 14, 647d), a rich source for Greek and Roman food history written about 200 c.e.:

Sweet almonds, hazelnuts, bitter almonds, poppy seeds: roast, watching them carefully, and pound well in a clean mortar. When well mixed, put into a small pan with boiled honey to moisten, adding plenty of pepper. It turns black because of the poppy. Flatten out into a square. Now pound some white sesame, moisten with boiled honey, and stretch two sheets of this, one below and the other above, so that the black is in the middle, and divide into shapes.

These instructions are one of the few remaining fragments of an ancient manual of bread and cake making by Chrysippus of Tyana in eastern Anatolia. He wrote in Greek at a time when eastern luxuries, captured in Roman wars, were all the rage in newly rich Italy. His audience may have consisted equally of educated Romans (Greek was the usual medium for scientific and technical texts) and their Greek-speaking cooks. This sweetmeat, its lost source, and its author are therefore evidence of an almost forgotten Mediterranean-wide gastronomic culture, as well as proof of a tradition of sweet specialties specific to certain Greek cities. All ingredients in gastris would have been locally sourced, with one exception: pepper, a rare, costly, and health-giving spice from southern India, which adds bite and exoticism. Thanks not least to Chrysippus himself, such local specialties would soon no longer remain local.

gelatin, the transparent protein extract (collagen) that is crucial for holding liquids in suspension, gives shimmering architectural jellies, Bavarian creams, and similar preparations their drama. Water molecules bond with gelatin molecules to produce an elastic solid (colloidal sol). About 7 grams (1 tablespoon) of gelatin will bind a pint of liquid. Powdered, granular, or sheets of commercial gelatin first need to be hydrated in liquid three to four times their volume; they are then activated by heating (usually the soaking bath), or by adding a sheet to the hot liquid preparation. In the refrigerator, the gelatin solidifies by cooling slowly to a lower temperature. The gelatin network continues to tighten its water-holding capacity, but after aging over a few days, the bonds begin to break and liquid escapes (syneresis).

Cooks originally boiled calves’ feet, skin, connective tissue, hartshorn shavings, or ivory dust to extract gelatin. Coastal cooks have used carrageenan and agar-agar made from red seaweeds such as Irish moss or dulse. In addition, isinglass, commercially extracted from the air bladders of some fish, also contains jelling compounds. (Cooked fruit purées, high in pectin, may also be molded.)

A molded gelatin dish is more easily released if the form is thinly coated with salad oil beforehand. When dipped in lukewarm water, the oil becomes fluid, but to break the 15 pounds of air pressure per square inch that holds the gelatin in the mold, the edges need to be loosened to allow air between the gelatin and container so that the gelatin will slide out.

See also gelatin desserts.

gelatin desserts, also known as jellies, are made by a centuries-old practice that attests to the maker’s exceptional skill. With today’s ready-to-use commercial products, the triumph of molded gelatins sparkling on a candlelit mahogany dessert board to the admiration of dinner guests has been forgotten.

Gelatins can vary in flavor, shape, texture, color, and content. Thanks to its transparency and water-holding capacity as a setting agent, gelatin is one of the most versatile ingredients in a dessert maker’s repertoire. The dazzling array of sweets that can be made from gelatin depends on several factors: the amount of liquid used, the flavoring components, and the treatment of the gelatin during the various phases of jelling: syrupy; slightly thickened; very thick; set, but not firm; firmly set.

When just ready to set, a fruit juice and gelatin mixture can be whipped into a light, opaque foam that is served after it has chilled and set. This type of gelatin foam is known as a whip, snow, or fluff. Fruit purée and chantilly (whipped cream) are often added to the foam to lend richness, and clear, colorful gelatin cubes or other ingredients may be folded in for embellishment. Sponges are similar to whips but incorporate beaten egg whites for more ethereal lightness. Both sponges and whips can be frozen to produce a semifreddo (the gelatin helps prevent the growth of large ice crystals). See desserts, frozen. Whipped gelatin preparations may also be used as jelly-roll fillings and for unbaked fruit or cream pies. See pie. For pies and tarts decorated with fruits, clear gelatin provides a shiny surface and helps keep the fruits and berries fresh. Although most fruits, including pineapple, can be treated this way, fresh pineapple must first be boiled for at least two minutes to denature the enzyme bromelain, which would otherwise liquefy the gelatin.

Classic French desserts, such as cold soufflés, Bavarian creams, and charlotte russes, all incorporate an egg-based custard (crème anglaise), whipped cream, fruit purée, and flavoring, usually a liqueur, which are stabilized with gelatin. See charlotte; desserts, chilled; and soufflé. These sweet jellies are beaten over ice until they begin to set; they are then poured into a distinctive mold and chilled before serving. A traditional Bavarian cream is molded in a ring form so that the accompanying sauce can fill the center, while a cold soufflé is served in ramekins or from a standard soufflé dish. A removable wax paper or tinfoil collar allows the mixture to set inches above the dish to resemble the rise of a hot soufflé. A charlotte russe is molded in a special tin that has been lined with a layer of sponge cake or ladyfingers. See sponge cake. The ingredients for these desserts can range from chocolate to any sweetened purée. For more predictable results, contemporary recipes for sweet mousses (mousselines) often suggest using gelatin in place of the tragacanth gum called for in older recipes. See mousse and tragacanth.

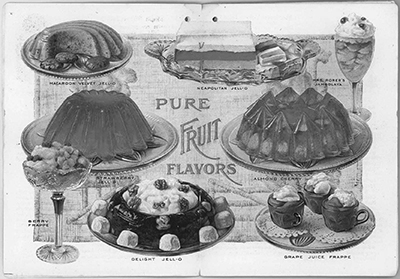

After Jell-O was introduced in 1900, gelatin desserts quickly became mainstream in the United States, since housewives had only to stir the brightly colored fruit-flavored powder with water and chill it to set. This circa 1910 advertisement from the Genesee Pure Food Company was accompanied by recipes for each dessert. At the time, Jell-O came in seven flavors and cost 10 cents a package.

Eighteenth-century wooden molds were replaced by salt-glazed pottery and, later, by creamware manufactured by Spode, Wedgwood, and other firms. Fruits, such as carved melons or citrus rinds, have also served as molds to highlight the fruit used. When decorating a mold, a thin layer of the clear gelatin should first be poured into the form and allowed to congeal, to become the top layer of the unmolded jelly. Fruits, flowers, herbs, gold or silver leaf, and other edibles are held in place by this initial film, which is then covered with additional layers. Great care must be taken in the layering process. If too much gelatin mixture is added, lighter fruits such as peaches, strawberries, blueberries, mandarin oranges, and sliced bananas will float out of place. Each succeeding layer of gelatin should be syrupy and at nearly room temperature. If the gelatin is too warm, it will liquefy the layer below; if too stiff, air pockets will form and affect the transparency and surface smoothness. For large architectural jellies, individual layers can be molded in increasingly larger forms, including cake and pie pans, which will become distinctive features in the finished dessert. All gelatins must be carefully unmolded from the base upward. By temporarily placing skewers throughout an elaborated layered jelly, the piece can be re-refrigerated to ensure that all the layers bond.

When a lower ratio of liquid is used, gelatin produces a chewable gum. Firmly set jelly can be cut into shapes with cookie cutters or made into sweets. Turkish paste is a jelly made from cooked fruit or dried-fruit purée cut into squares and coated with powdered sugar or nuts. See lokum. Homemade marshmallows as well as the candy called pastels are made by incorporating whipped egg whites into syrupy gelatin and beating the mixture. See marshmallows.

In the United States, gelatin desserts quickly became mainstream with the introduction of the commercial brand Jell-O in 1900 by the Genesee Pure Food Company. This brightly colored fruit-flavored powder was extremely easy to use; it had only to be stirred with water and chilled to set. By the mid-twentieth century Jell-O, and all sorts of desserts and salads based on it, had become a quintessential American food, living up to its early moniker as “America’s Most Famous Dessert.”

The popularity of gelatin desserts has not waned, but the desserts themselves have been reconfigured for a more sophisticated audience. Although ready-made gelatin mixes like Jell-O line grocers’ shelves, fashionable restaurants nevertheless frequently include house-made gelatin-dependent desserts or elements in their elaborately constructed presentations.

See also gelatin.

gelt, chocolate “coins” (from the Yiddish טלעג, for money or gold), are given to children as part of the current Jewish celebration of Hanukkah, the holiday commemorating the victory of the Maccabees over the Seleucid Greeks in 165 b.c.e. Special triumphal coins were struck after the victory, possibly serving as the inspiration for modern Hanukkah gelt. In any case, gelt started out as real coins given out, variously, as donations to the poor for ritual candles, as an incentive for children to study (as Maimonides taught), or as a bonus to teachers.

How chocolate gelt replaced real coins is a matter of colorful speculation, including the alleged prominence of Jews in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century chocolate manufacture. More concretely, in Belgium and the Netherlands, the feast of St. Nicholas (Sinterklaas or Santa Claus), which takes place on 6 December during the heart of the Hanukkah season (ranging from late November to late December), includes the offering of both chocolate and real coins (Geld) to begging students and children. It would be a mistake to draw too close a connection between this Christian tradition and Chanukah gelt—gelt is today a major part of Chanukah observance in Israel—but in America, where cultural assimilation has increasingly established Chanukah as a Jewish “Christmas,” gelt can function as a comfortable alternative to Christmas presents. From modest beginnings by the U.S. chocolatiers Lofts and Barton’s in the 1920s, the industry now offers the pious parent gold or silver foil-wrapped kosher-neutral (pareve), dairy (milchik), nut-free, and even Ghanaian fair-trade gelt.

See also hanukkah and judaism.

gender in relation to sweets is a complex and multilayered subject, at least in Western societies. The English language adage “girls are made of sugar and spice and everything nice” encapsulates a widespread perception, reinforced by advertising and popular culture, that pairs women with sweetness and desserts. Countless Hollywood films present women gorging on ice cream and other sweets when abandoned by a lover or otherwise sad. This kind of response is rarely depicted with males, unless they are weak and overweight characters marked as “losers.” In contemporary U.S. popular culture, whose global impact and marketing penetration are difficult to deny, women are presented as closely connected with and attracted to chocolate. In particular, bonbons and bite-sized delights reflect ideals of moderation while simultaneously expressing acceptable forms of eroticism and indulgence that can be enjoyed in solitary rapture. See bonbons.

Rationalizations of these representations vary from scientific arguments that point to serotonin and dopamine levels in the premenstrual period and the significance of phenyl ethylamine and its endorphin-like effects on women’s moods, to moral discourses that decry women’s weakness and their inability to control themselves. Larger portions of chocolate are instead perceived as acceptable for male consumption—bars were provided to soldiers during World War II and many Europeans still remember American GIs distributing chocolate as they entered liberated territories. See military. In reaction, feminists have been keen to point out how these social customs and cultural notions are the result of oppressive power relationships, reinforced by pervasive advertisements that almost exclusively market ingredients and products for the domestic preparation of dessert and cake to women.

Other Times, Other Places

When it comes to sweets and gender, it is important not to generalize Western norms, ideas, and practices, since at other points in space and time the relationship is less marked, as in sub-Saharan Africa or Eastern Asia, or it is structured according to different notions. See sub-saharan africa and east asia. For instance, in India, a country where desserts are pervasive and infinitely varied, on Bhai Phota (Brother’s Day, also called Bhai Beej) sweets are presented to brothers and male members of the family. In the past, baby boys had their lips smeared with sweet substances before their first feeding, while fish was reserved for girls. Sweets are also strongly associated with weddings, regardless of the couple’s religion.

In the Middle Ages, when sugar was still so rare in Europe that it was considered a spice, dessert production tended to fall into the domain of male specialists, especially for upper-class clients or for official occasions such as banquets and celebrations. Not only professional chefs and confectioners, but also pharmacists relied on technical skills honed by years of experience, and they were highly appreciated in the public sphere. In Italy, however, it was not unusual for women to produce pastries for sale, the same way they engaged in fresh pasta manufacture or cooked in family-owned eateries. As for consumption, sugar was not especially connected to gender. Rather, it was an expression of status and wealth due to its high cost. Yet dainty sweets were already associated with women—there is mention of drageoirs (elegant containers for sweets) being offered to the female guests at the wedding of Henry IV of England, while males were presented with plates of spices. As with any other edible substance, until the seventeenth century, the physiological qualities of sugar were framed in the medical and nutritional theories that considered the human body as regulated by four humors: blood, yellow bile, black bile (or melancholy), and phlegm, which also fell under the categories of hot, cold, moist, and dry. Although sugar was supposed to help warm the stomach during digestion, it was recommended that women avoid consuming it in excess because its moist nature would increase a woman’s inherent moistness, turning her lazy and phlegmatic, while its hotness could make her more choleric and less feminine. See medicinal uses of sugar.

Romantic Sweets

From the eighteenth century on, upper-class women in France and England, as well as in other European countries, gathered in elegant cafés and consumed pastries with their beverages. They also patronized refined confectionery shops whose décor and service catered to the taste of the female clientele. As sugar became more available and its price fell, working-class women were able to add sugar or molasses to their tea, while upper-class women turned more to candies and dainty chocolate. See chocolate, luxury and chocolates, boxed. Sweets came to symbolize men’s romantic interest in women, a custom that continues today on Valentine’s Day and, to a lesser extent, on Mother’s Day. See valentine’s day. Romantic messages were at times wrapped in paper that carried amorous messages, a peculiarity that is still found in Italian Baci chocolates. The connection between desserts and courtship was reflected also in the popularity of wedding cakes, larger and more spectacular than those used on other occasions, probably an echo of the stunning cakes consumed during noble banquets when sugar was still a luxury. See wedding cake.

Sex and Religion

Well into the nineteenth century, in Catholic areas of the Mediterranean like Sicily and Spain, nuns were renowned for their confectionery preparation, and in certain places this is still the case. See convent sweets. It was not unusual for the daughters of noble families to be forcibly sent to a convent, where they learned to prepare delicious desserts that were then consumed by the upper classes. Nuns renounced the temptations of the flesh but toiled in the kitchen for others’ delectation, reinforcing social and gender structures of power. The connection between nuns and sweetness was ironically consecrated by lay desserts such as barrigas de freiras (nun’s bellies) in Portugal and pets de nonnes (nun’s farts) in France.

These forms of irreverence connecting sweets and sex have ancient roots. The minnuzzi ri Sant’ Ajita (Saint Agatha’s little breasts) are little cassata cakes with a cherry on top that take their name from the martyr Saint Agatha, who had her breasts cut off. This specialty from Catania, Sicily, dates back to antiquity, when the followers of the goddess Isis—a symbol of motherhood—consumed sweet breast-shaped pastries to worship her. In Rome, the harvest goddess Demeter was associated with honey and flour sweets shaped like female genitalia, and the god Priapus—representing male potency—was honored with penis-shaped pastries. To this day, penis cake pans are available in novelty and sex stores, while erotic cakes shaped as sexual organs or representing sexual acts mark occasions like bachelor and bachelorette parties, where desserts are supposed to allude to upcoming postnuptial pleasures.

Advertising and Popular Culture

As candy and sweets became mass-produced and their consumption expanded during the Gilded Age, advertising and popular culture increasingly connected them to males—especially in the form of candy bars—as a sustaining source of energy and as a remedy against the temptations of alcoholism. See candy bar. Simultaneously, bonbons—pure, graceful, and refined—were gradually presented as objects of female desire. As Western—and in particular American—products are making their way into other markets, these perceptions are being presented to populations that either did not traditionally consume great quantities of sweets or did not attribute any gender connotations to the consumption of sweets. The increased availability of snacks and desserts is thus shaping new needs and desires, influencing gendered notions attached to them.

See sponge cake.

Germany is no exception to the general rule: for ancient Germans, as for others, sweetness was rare and highly coveted. Under Roman cultural influence from the first century b.c.e. until the fifth century c.e., apiculture became more sophisticated and honey more available, but the cultivated sweet fruits (cherries, plums, and apples) introduced by the Romans were regarded as a great luxury and reserved for those of high social standing. From the tenth century on, cane sugar from the Mediterranean was available, but for a long time it remained as expensive as exotic spices and was treated like medicine. See medicinal uses of sugar. At the end of the fourteenth century in Cologne, refined sugar was still more expensive than either ginger or pepper, with a pound of loaf sugar worth more than 16 liters of honey. Nevertheless, the quantity of sugar sold steadily rose throughout the fifteenth century, and by the 1450s sugar prices had fallen below those of ginger and pepper. But for far longer than elsewhere in Western Europe, honey was the Germans’ sweetener of choice, often combined with sweet and tart fruit. See honey.

It was only in the mid-sixteenth century, after the founding of Germany’s first sugar refinery in Augsburg in 1573, that sugar began to be indicated for culinary use, supplementing the honey in early gingerbread recipes. Sabine Welser, from a wealthy, patrician family, used sugar very liberally in her manuscript recipes for pies and tarts, and Marx Rumpolt, in his Ein new Kochbuch (1581), was the first to include a chapter devoted to Zucker-Confect, or sugar confections. Nowhere in his book is honey mentioned, perhaps, as he makes clear, because marzipan and Zucker-Confect are banquet foods reserved for the nobility. See marzipan. On the rare, festive occasions when peasants could afford sugar, they tended to use it ostentatiously, sprinkling it over millet gruel, a festive dish served at weddings and christenings until well into the eighteenth century.

As elsewhere in Europe, sugar developed into an indispensable partner for coffee, tea, and hot chocolate. Following the example set by the French court, Germans not only sweetened the new, bitter-tasting beverages with sugar but also served sweet pastries or desserts alongside them, provided by Conditoren or Zuckerbäcker, literally “sugar bakers.” In the seventeenth century Hamburg was the leading center in Germany for sugar refining and the sugar trade, due to the city’s large number of Dutch refugees from the Thirty Years’ War, who were already familiar with sugar from their Caribbean plantations. See plantations, sugar; sugar refining; and sugar trade.

Scarcity

Sugar production altered dramatically in 1747, when Andreas Sigismund Marggraf and Franz Carl Achard successfully produced sugar from mangelwurzel (Beta vulgaris), known today as the sugar beet. See sugar beet. In 1800 Germans consumed, on average, 1 kilo of sugar per year, about double what they had eaten a hundred years earlier. However, beet sugar really took off only in the 1840s, and between 1875 and World War I Germany became one of the world’s great sugar exporters. Having become accustomed to ample and widely affordable provisions of sugar, Germans were forced to face scarcity due to wars and economic crises. See sugar rationing. During the British blockade in World War I, even seemingly abundant crops such as potatoes and sugar beets were quickly reduced to scarce commodities as people turned to them to compensate for the lack of fat and meat. In addition, the armament industry used fat and sugar to replace blocked imports of glycerine, which was necessary for the production of nitroglycerine explosives. The government also exported sugar, potatoes, and coal to neutral countries in exchange for raw materials to use in German factories. During World War II women developed their own methods of preparing starch from potatoes and syrup from sugar beets. Culinary ingenuity resulted in ersatz treats such as marzipan look-alikes made from grated potatoes or semolina mixed with a little sugar and artificial bitter-almond flavoring. See trompe l’oeil. Postwar CARE parcels always contained sweet foods such as canned and dried fruits, honey, chocolate, and sugar, making sugar readily available once again. On the Berlin black market in 1947, 1 kilo of sugar could be had for 7 or 8 American cigarettes, while 1 kilo of various kinds of cooking fat cost 23 to 25.

In the 1950s there were still limits on food consumption for most people, but Sundays as well as holidays were once again marked by special meals, including sweets, whether stollen for Christmas or a chocolate pudding for Sunday dessert. See stollen. Despite the overall constraints, concerns about overindulgence set in, and sugar (along with fat and overcooking) came to be regarded as the enemy of good health and slimness. Quark and milk, boiled fish, and boiled eggs were recommended, whereas tortes, chocolate, and whipped cream were blacklisted as sweet indulgences. See torte. By the 1980s dieting had become enormously popular, and so-called light products—diet foods with reduced sugar content or artificial sweeteners—proved a very successful new market for the food industry. In 1878 saccharine (first marketed in 1885) had been developed by a German chemist. This first artificial sweetener was readily embraced by the public (thereby alarming the beet-sugar industry), as rising affluence caused health problems such as obesity and diabetes, both of which were discussed as much in 1900 as they are today. In 1937 that original synthetic sweetener was joined by Cyclamat (sodium cyclamate); both stood in for sugar during the war. Today, agave nectar and concentrated fruit juices, mainly from apples, pears, and grapes, as well as all kinds of brown cane sugar and Stevia, are perceived as healthier and are used in place of white beet sugar in so-called health foods and organic products. See agave nectar and stevia.

Characteristic German Sweets

In Germany, sweet foods are not limited to dessert. It is often said that the combination of spices, sweetness, fruit, and acidity still found in contemporary dishes such as sauerbraten is a German peculiarity, a medieval remnant proving the cuisine’s backwardness. But this proclivity for sweet and sour can also be seen as a positive continuum. The French philosopher and politician Michel de Montaigne, traveling in the south of Germany at the end of the sixteenth century, commented favorably upon the meat served with cooked plums, pears, and apple slices, a custom that survives in the form of the poached pears and cranberries served with roast game to this day. In this context, it is interesting to note that with the pseudo-internationalization of food following World War II, Asian cuisine in Germany came to be associated with a number of sweet and sour recipes, typically involving canned pineapple.

Germany has a vast array of candies, many of which come from Haribo’s wide selection of fruit gums (most notably Gummi Bears), licorice, chewy fruit candy, and marshmallows. See gummies; haribo; licorice; and marshmallows. In the late nineteenth century the first vending machines began to sell chocolate and other sweets, and later chewing gum and dextrose, often with cheap trinkets or collector’s cards thrown in as additional temptations. Brausepulver, the German version of sherbet powder, merits special mention in no small part because it features in one of the most sweetly innocent sexual awakenings on film, when the protagonist in The Tin Drum (based on Günter Grass’s novel) pours it into his girlfriend’s belly button, spits into it, and licks up the foaming concoction. See sherbet powder. Brausepulver has recently seen a nostalgic comeback. Chocolate remains a popular sweet, typically in the form of Tafeln, flat, square 100-gram bars. Germany is split between a recent foodie-driven rise in bitter dark chocolate with its higher cacao content and the much-loved milk chocolate, especially Kinderschokolade and the famous Überraschungseier, “surprise eggs.”

The picture of sweet Germany would be greatly imbalanced without mentioning Kaffee und Kuchen, coffee and cake served in the afternoon in private homes or consumed in the country’s numerous cafés or Konditoreien. See café and kuchen. It is an informal way to mark a special event with a meal and can also serve as an excuse for (mostly female) friends to meet for a chat, referred to by the old-fashioned term Kaffeekränzchen or Kaffeeklatsch (coffee klatsch).

Until World War II home baking tended to be the norm, except for large sheet cakes, which in rural areas were brought to the local baker since they did not fit inside domestic ovens, and some households did not even have ovens. However, once the economy began to recover in the 1950s, housewives tended more often to buy prepared goods from the baker or Konditor, in particular, Teilchen or Stückchen (individual portions of cake) and small Danish pastries (Plundergebäck) filled with custard, almond paste, or fruit. For more festive occasions simple kuchen (mostly variations on pound cake) were, and still are, replaced by filled and garnished Torten, of which the most famous is arguably Schwarzwälder Kirschtorte. See black forest cake. Equally popular for dessert is ice cream, which is served instead of cake in the summer, often in elaborate concoctions involving fruit, sauces, and whipped cream. In many regions, for a quick and simple Saturday lunch, a stew or hearty soup is followed by a sweet dessert. The Pfalz region is known for Grumbeersupp un Quetschekuche, potato soup traditionally eaten with a plum sheet cake made with a yeast dough. Once-popular cold fruit soups were formerly served for light summer lunches, a tradition that has nearly disappeared. See soup. Other old-fashioned sweet foods, such as baked or steamed yeast dumplings (Rohr- or Dampfnudeln), remain popular in the south. The dumplings, sometimes filled with fresh fruit or jam and served with vanilla sauce, take the place of cake. See dumplings. In the winter, baked apples are popular.

Before the days of Dr. Oetker’s instant custard powder that need only be mixed with milk and brought to the boil, Schokoladenpudding was a favorite chocolate “pudding” made with eggs, like real custard. See oetker. In many regions a kind of trifle, Götterspeise (literally, “the dish of the gods”), is made with custard, cream, jam, or fruit and sponge cake (dark pumpernickel bread is also used in the north). In the north of Germany, Rote Grütze, a mix of red fruit and berries thickened with various kinds of starch or gelatin, has been introduced from Scandinavia. See pudding and trifle. Throughout Germany, fruit quark and farina pudding are popular, and Kompott, stewed fruit, is seeing a comeback.

As for holiday specialties, Easter brings lamb-shaped sponge cakes dusted with confectioner’s sugar and bearing a small flag reminiscent of church processions, as well as chocolate bunnies and eggs with various fillings, wrapped in colorful foil. For Carnival a wealth of small pastries deep-fried in lard are made in numerous regional variations. See carnival; fried dough; and holiday sweets. In the Rhineland, with its riotous parades, Kamellen (the local dialect for Karamellen, hard candies) are thrown into the crowd from the floats. Before Christmas children receive Advent calendars filled with chocolate or little gifts, and many towns feature an open-air Weihnachtsmarkt (Christmas market or fair), with many stalls offering Glühwein (mulled wine) and all kinds of Lebkuchen, as well as other candies and sweets. See fairs; gingerbread; and mulled wine. On the evening of 5 December, children put out their polished shoes for Nikolaus (St. Nicholas), a cousin of America’s Santa Claus, to fill them with goodies during the night. The treats traditionally consist of oranges, mandarin oranges, nuts, gingerbread, marzipan, and chocolates, but today small presents are often included. Throughout the entire Advent period, Weihnachtsbäckerei (Christmas baking) plays an important role. It is often an occasion for friends to gather, with children joining in. The most traditional German Christmas cake is stollen, but cakes with a poppy seed filling rolled up in a yeast dough are another Christmas tradition, with Silesian roots.

Ghirardelli, more than just chocolate, encompasses the story of immigration, the power of marketing, and the circle of urban renewal.

Italian-born Domingo Ghirardelli (1817–1894) founded Ghirardelli Chocolate Company in San Francisco in 1852. He had apprenticed at Romanengro’s confectionery shop in Genoa before immigrating to Peru, where he opened his own shop, specializing in chocolate. While in Peru, Ghirardelli met fellow entrepreneur and land baron James Lick who, upon returning to the United States, sent word of the California Gold Rush to Ghirardelli.

Ghirardelli moved to California in 1849 and opened a general store in the town of Stockton, where he sold provisions, including chocolate, to successful miners who were looking for a taste of luxury. In the early 1850s he opened a second shop in San Francisco, which sold liquor, spices, coffee, and chocolate.

Three developments allowed the business to expand. The 1867 invention of the Broma process, which removes butterfat from cocoa solids without the use of alkalis, enabling the cocoa to mix easily with water or milk, allowed the chocolate to be shipped without turning rancid. Second, shipping possibilities expanded greatly with the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Finally, mass marketing and advertising during the Gilded Age—including a popular campaign about how to pronounce “Ghirardelli”—further drove demand for the chocolate confections. As a result, the business expanded to become the largest chocolate producer on the West Coast.

In 1893 the company acquired a textile mill on North Point Street in San Francisco. Over the decades, Ghirardelli built several additions to the structure, and the company remained in that location until 1964, when it relocated to San Leandro. The property was purchased by locals who wanted to save the building, which reopened in 1964 as a mixed retail space of shops and restaurants. A model for urban renewal in Boston and Baltimore, the complex, called Ghirardelli Square, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.

The company itself underwent several changes. Golden Grain Macaroni acquired Ghirardelli in 1963, and as of 2013, it had become a subsidiary of chocolate makers Lindt and Sprüngli. Today, the company remains a bean-to-bar manufacturer, focused on premium quality, whose product line includes a range of bars, baking mixes and sauces, and cocoa powders.

See also chocolate, post-columbian; cocoa; and guittard.

Gilliers, Joseph (d. 1758) is best remembered as the author of Le cannameliste français, which was the most extensive manual for working with sugar written in the ancien régime. Published in 1751, the very year in which Diderot and d’Alembert brought forth the first volume of their famous Encyclopédie, the Cannaméliste français similarly features an alphabetized, dictionary-style format, reflective of the Enlightenment. Gilliers invented the word “cannameliste” from “canne” (sugar) to imply a person who works with sugar, so his book’s title might be translated as “The French Sugar-Worker.”

The book provides instructions for how to perform the wide-ranging functions of the office, the division of the kitchen in large, European households that created desserts in addition to preparing salads and liqueurs; supervising table settings and decoration; and caring for linens, silver, and the like. It includes advice about how to store fruits or transform them into jellies, as well as the best methods for making artificial flowers. The volume’s extensive recipes for iced fruits, creams, and fromages glacés (which, confusingly, usually do not contain cheese) were among the first and most original in Europe. Gilliers also provided detailed instructions and diagrams for how to mold these iced confections into fanciful shapes imitating asparagus, boars’ heads, fish, and other unexpected forms. See ice cream.

Le cannemaliste français is most famous for its lavish, foldout engravings. Gilliers’s designs for S-curved tables and intricate, three-dimensional surtouts de table, which sat in the center of the fanciest tables, exemplify the rococo style that flourished in mid-eighteenth-century France and betray a familiarity with the designs of the style’s most renowned practitioner, Juste-Aurèle Meissonier (1695–1750).

Little is known about Gilliers’s early life, except that he worked as a Chef d’Office for King Stanislaw Leszczyński (1677–1766), at the Château de Lunéville. The property belonged to the Duchy of Lorraine, which was given to Leszczyński in 1738 by his son-in-law, French king Louis XV (r. 1715–1774), as compensation for abdicating the Polish throne. It is presumed that Gilliers was a local boy from the region. He reported to M. François Richard, the Contrôleur des Offices who had worked for the deposed king since the time he had resided at the Château de Chambord (1725–1733). Gilliers was merely one of six assistants, who were further aided by two kitchen boys. Leszczyński also employed a full-time party planner, M. Dupuis, who held the title Dessinateur des plaisirs. All these workers, not to mention an extensive kitchen staff and other servants, reported to the Duke de Tenczin Ossolonski (1666–1756), the Grand Master of the Household, to whom Gilliers dedicated his book.

This large retinue sustained one of the most renowned pleasure palaces in Europe, which operated as something of a rival to the court of Versailles, especially after Madame de Pompadour (1721–1764) became the French king’s mistress in 1745 and virtually ruled the realm, setting both policy and fashion. Leszczyński’s daughter Marie (1703–1768) was the French king’s wife, so, as a protective father, he naturally hoped to outshine the woman who had turned his son-in-law’s head away from his beloved child.

The deposed ruler, who had failed so miserably at politics in Poland, excelled at hosting pleasurable, light-hearted entertainments and had a noted taste for the desserts and ices that featured at such events. He had, in fact, previously employed another famous Chef d’Office, Nicolas Stohrer, who joined Leszczyński’s service during his 1719–1725 stay in Wissembourg. See stohrer, nicolas. Stohrer left to join the queen’s household when Marie married Louis XV in 1725, and then opened his own pastry shop on the rue Montorgueil in Paris. It is currently the oldest in the city.

If Gilliers’s book disseminated the style of the extraordinary parties held at Lunéville as much as the recipes for appropriate sweets to serve at them, his designs seem downright conservative compared to engravings by architect Emmanuel Héré de Corny (1705–1763) of the wonders he had created at Lunéville, which included a grotto populated by 86 automatons in an idealized village as well as several whimsical garden pavilions used to stage the king’s frequent banquets. A Turkish-inspired kiosk included a hydraulically powered table, which could rise up from the basement, and which was surmounted by an intricate porcelain surtout that depicted a pastoral landscape and sprayed jets of water.

Gilliers’s masterwork records Lunéville’s attenuated elegance, and its logical organization simultaneously reflects Leszczyński’s court as a hub of Enlightenment thinking, where Voltaire (1694–1778), for example, was a frequent guest and where the former Polish king created and oversaw his own academy. However, the greatest importance of Le cannameliste français lies in its clearly written recipes, which, from ice cream to biscuits, helped popularize beyond this rarified universe many desserts that have become commonplace today.

See also dessert; dessert design; france; and serving pieces.

See spices.

gingerbread is a term that applies to a broad category of baked goods flavored with a combination of spices such as ginger, cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg, and sweetened with honey, sugar, or molasses. Gingerbreads range from cakes to breads to cookies. Made from batters or doughs, and shaped in many forms, they can be soft or hard, thick or thin, glazed or unglazed, unadorned or decorated with icings, dried or candied fruits, nuts, marzipan, colored paper, or even gold leaf. Gingerbreads are closely associated with the Christmas season in several countries, but in many places they are also eaten year round. Although most gingerbreads are sweet, some are used as an ingredient in savory dishes, such as rich soups and sweet-sour sauces. Slices of gingerbread are often served as an accompaniment to fattened goose liver and duck liver.

Gingerbread History

Archeaological evidence shows that flat cakes made with honey and spices were baked by the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans. See ancient world. But the gingerbreads eaten today are descendants of those developed in northern Europe in the Middle Ages, when honey was the main sweetener available locally, and exotic, expensive spices were increasingly being imported from faraway lands in the East to satisfy the medieval desire for highly spiced foods. See honey and spices. Honey-and-spice gingerbreads were first made in Christian cloisters and monasteries, before production shifted to professional bakers’ guilds, and much later to home bakers. See guilds. A taste for gingerbread eventually spread throughout northern Europe, with certain cities becoming known for their own particular types of gingerbread: Ashbourne, Ormskirk, Grasmere, and Edinburgh in the British Isles; Paris, Strasbourg, Dijon, and Rheims in France; Dinant in Belgium; Nuremberg (Nürnberg), Aachen, Ulm, and Pulsnitz in Germany; Basel and St. Gallen in Switzerland: Toruń in Poland; Prague and Pardubice in the Czech lands; Pest in Hungary; Tula and Gorodets in Russia. Gingerbread recipes later spread around the world with Europeans who emigrated to North and South America, Australia, New Zealand, and parts of Africa.

This lithograph of The Gingerbread Seller is from the series The Cries of Paris engraved by François Seraphin Delpech (1778–1825). Gingerbread, or pain d’épices, was often shaped in whimsical forms. musée de la ville de paris, musée carnavalet, paris / bridgeman images

Many early gingerbreads were made from a dough of rye flour and honey, flavored with spices that included cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, anise, and ginger or pepper. Often the mixture was left in a moderately cool place for several months to ferment slowly like a sourdough, to develop the enzymes essential for the gingerbread’s taste, texture, and preservation. After the remaining ingredients were added, the dough was shaped and baked. Over time, the variety of ingredients used in gingerbreads expanded to include wheat flour, eggs, butter, cane sugar, beet sugar, molasses, golden syrup, maple syrup, allspice, coriander, cardamom, saffron, almonds, hazelnuts, walnuts, currants, raisins, dates, grated lemon zest, candied orange peel and citron peel, rosewater, rum, brandy, milk, buttermilk, beer, licorice, crushed rock candy, crystallized ginger, and chemical leavenings. However, some baked goods called “gingerbreads” do not contain any ginger at all.

During the Middle Ages, the German city of Nuremberg—located at the crossroads of two major trade routes and surrounded by forests full of honeybees—became one of the most famous places for making gingerbreads in Central Europe. The German term for these seductive sweets was Lebkuchen (or sometimes Pfefferkuchen, when their spiciness came from pepper instead of ginger). The stiff dough was pressed into highly detailed molds, usually made of carved wood, which imprinted intricate designs on top of the Lebkuchen before they were removed from the molds and baked in a hot oven. See cookie molds and stamps. The size and shape of the Lebkuchen were determined by the design of the molds, which ranged from a few inches to 3 feet tall and often depicted members of the nobility, religious figures, and coats of arms. Nuremberg Lebkuchen contained such costly ingredients, and was of such high quality, that it was sometimes used as payment for city taxes, and gilded Lebkuchen were given as special gifts to nobles, princes, and heads of state.

In the British Isles, gingerbread making dates from the fourteenth century, when the earliest gingerbreads were confection-like combinations of breadcrumbs, ground almonds, honey or sugar, and ginger. Originally eaten only by the upper classes, gingerbreads made with flour, treacle, and spices later became popular treats sold at markets and fairs. See fairs. Legend has it that Queen Elizabeth I enjoyed gilded gingerbread cookies baked in the shape of her suitors, courtiers, and guests, and that four centuries later Queen Victoria popularized gingerbreads as a British Christmas tradition. An old Halloween custom in northern England was for a maiden to eat a gingerbread cookie shaped like a man, to ensure she would soon find a husband. And witches were sometimes accused of baking and eating gingerbread effigies of their enemies. Gingerbreads shaped like pigs and men are still traditional for Bonfire Night (5 November) in Great Britain. See anthropomorphic and zoomorphic sweets.

In Europe, as the demand for gingerbread increased and the prices of ingredients fell, faster production methods were developed. In the nineteenth century metal molds and cookie cutters, often mass-produced and less detailed in design, began to replace the elaborate handmade wooden molds of earlier times. Instead of intricately embossed designs on the dough, simpler decorations were added on top of the gingerbread cookies: nuts, candied fruit, sugar icings, and paper cutouts printed with seasonal or topical motifs. Shapes were simplified, too, eventually becoming the basic human, animal, and geometric forms common today. Artisanal bakers continued to leaven their dough with the natural yeasts present in it, but industrial bakers and home cooks began using baking soda, potassium carbonate, or ammonium carbonate to speed up the process. See chemical leaveners.

Making gingerbread houses became a popular activity in Germany in the early 1800s. Ornately decorated heart-shaped Lebkuchen cookies also became a fad in Germany and Austria during the nineteenth century. Adorned with fancy designs and romantic sayings made from colored icing or printed paper cutouts, these large Lebkuchen hearts were often exchanged between sweethearts and given to wedding guests. They are still a popular souvenir at many Central European festivals and Christmas markets.

In some European countries, gingerbreads were a traditional food at many religious and secular events: Christmas, Easter, baptisms, birthdays, saints’ days, a child’s first day at school, conscription into military service, and departures on journeys. Elaborately decorated gingerbreads were often used as decorations, to be kept and displayed instead of eaten. An old custom still practiced in Central Europe and Scandinavia is to hang gingerbread cookies on evergreen boughs and Christmas trees in the house, and to display fancy gingerbread cookies in windows during the winter holiday season.

Gingerbread Varieties

In Germany today, Lebkuchen are produced in many sizes, shapes, flavors, colors, and textures: rounds, rectangles, squares, hearts, stars, pretzel forms, St. Nicholas (for the Christmas season), lucky pigs (for New Year), and rabbits (for Easter). See holiday sweets. The Lebkuchen dough ranges from “white” (light-colored) to different shades of brown. German Lebkuchen can be covered with white or chocolate icing; filled with marzipan or jam; or decorated on the top or bottom with whole or chopped almonds. Some versions are sweetened only (or primarily) with honey. Oblaten Lebkuchen are cookies whose dough is baked on top of a paper-thin edible wafer. Delicate, elegant Elisen Lebkuchen are a type of Oblaten Lebkuchen made with finely ground almonds, hazelnuts, or walnuts, and little or no flour.

Other types of gingerbread cookies—with a variety of different ingredients, shapes, colors, textures, and decorations—are known as Printen, Honigkuchen, and Pfefferkuchen in Germany; Spekulatius in the German Rhineland, speculaas in the Netherlands, and speculoos in Belgium; Leckerli, Biberli, and Tirggel in Switzerland; pepperkaker in Norway, pepparkakor in Sweden, piperkakut in Finland, and pebernǿdder and brunekager in Denmark; piparkūkas in Latvia and piparkoogid in Estonia; pain d’épices in France; licitar in Croatia; mézeskalács in Hungary; perníky in the Czech Republic and Slovakia; turtă dulce in Romania; medinki in Bulgaria and medianyky in Ukraine; pierniki and pierniczki in Poland and prianiki in Russia; ginger biscuits and ginger nuts in British Commonwealth countries; and gingersnaps in many English-speaking countries. Some towns and regions also have specific names for their own particular varieties of gingerbread cookies, including those made for local and regional holidays. Some of these cookies are elaborately decorated with white or colored icings, candies, paper cut-outs, and even small mirrors, often with designs that have local cultural or religious significance.

The category of gingerbreads also includes many kinds of spice cakes. Leavened with soda, beaten eggs, baking powder, or sometimes yeast, they are made with the same spice combinations used in gingerbread cookies, usually have a somewhat dark color and dense texture, and are baked in many forms—flat, tall, round, square, rectangular, layers, and loaves. These include several kinds of British spice cakes, such as parkin made with oatmeal and treacle; Slavic honey cakes often made with rye flour and a smaller range of spices; and American gingerbread cakes, loaves, muffins, and cupcakes. Slices of gingerbread cakes are often garnished with lemon sauce, vanilla ice cream, or whipped cream.

Gingerbreads are popular in many parts of the world today because they are easy to make, use relatively inexpensive ingredients, are richly flavored, and can be baked in many forms. Gingerbread cookies, especially those cut in the shapes of gingerbread men and women, are particularly beloved by children. Amateur and professional bakers see gingerbread cookies as a blank canvas for their creativity in decorating with icing and other edible materials. The making of gingerbread houses at Christmas has spread from their origin in Germany to other countries around the globe, and gingerbread house contests have become popular community events in many places. Every year since 1991, the city of Bergen, Norway, has even sponsored the world’s largest “gingerbread city” (Pepperkakebyen), a miniature city composed of more than 2,000 colorfully decorated and lighted gingerbread houses and other gingerbread buildings constructed by local children of all ages.

See also christmas; easter; germany; leaf, gold and silver; molasses; netherlands; russia; scandinavia; and speculaas.

See candied fruit.

See icing.

glucose (also called dextrose in the food industry) is a monosaccharide—the most basic form of carbohydrate—commonly obtained from plants, which manufacture it through the process of photosynthesis. Glucose is the main energy source for humans and most other organisms.

When consumed, glucose is absorbed by the intestines into the blood. In response to the rise in blood-glucose levels, the pancreas releases insulin, the central metabolic hormone. Cells that need glucose have specific insulin receptors on their surface, permitting glucose entry into the cells. When present in the blood, insulin directs some tissue cells to take up glucose, other cells to store glucose (in the form of glycogen) in liver and muscle cells, and still other cells to hold lipids (fats) in adipose tissue (body fat). Insulin’s absence signals cells to turn off the uptake of glucose, break down glycogen, release lipids from adipose tissue, and put glucose into the bloodstream. When oxidized in the body, in the process called cellular respiration, glucose provides energy for cells; carbon dioxide, and water are the waste products of that process.

Pure glucose has little flavor or color. Common table sugar (sucrose) is a disaccharide consisting of 50 percent fructose and 50 percent glucose. In the early nineteenth century, the starch from potatoes, sweet potatoes, and corn was converted into glucose syrup. By the beginning of the twentieth century, glucose was commonly used as a sweetener and sold as corn syrup, such as Karo syrup. See corn syrup. A similar chemical process can convert glucose into fructose, a much sweeter monosaccharide.

See also fructose and sugar and health.

Godiva is arguably the best known today of the large chocolate factories that emerged in Belgium in the late 1870s, arising mostly out of small, artisanal shops that served a fancy clientele. Mechanization and improvements in packaging and marketing led to the growing popularity of chocolate as its price declined. By the 1920s, chocolate had become a common treat that all social classes enjoyed. In the late 1940s, average per capita consumption was 1.1 kilos; by the 1970s, it had grown to 4.2 kilos per person, and it is close to 10 kilos today.

In the late 1920s, the Brussels area had some 90 chocolate manufacturers, including Joseph Draps, who, together with his family, produced pralines that were sold by local department stores. In 1945 the company opened its first shop in an upscale Brussels district and a second one in chic Knokke (on the Belgian coast), naming the products “Godiva,” after the Anglo-Saxon legend of the woman who rode a horse naked to urge her husband to reduce taxes (her tactic was effective). Success came quickly and Draps opened more shops, including one in Paris in 1958, one on New York’s Fifth Avenue in 1966, and one in Tokyo in 1972. The Campbell Soup Company became interested in this successful Belgian chocolatier and purchased the company in 1972. In 2007 Campbell sold Godiva to the Turkish Ülker Group. Today, Godiva has almost 10,000 points of sale all over the world and offers approximately 60 products, including the 72 percent Dark Chocolate Bar and Citron Meringue praline.

Godiva’s success may be linked to the company’s lowering of costs, finely tuned marketing, wealthy clientele, high-quality products (Belgian chocolate contains at least 35 percent cocoa butter, sometimes up to 85 percent), and continuous innovation in its product range. Godiva’s history represents a genuine Belgian chocolate culture that has existed since the 1890s, when chocolate was first perceived as healthy, providing quick energy at a relatively low price, giving comfort in difficult psychological moments, and a genuine treat enjoyed on special occasions, such as the very popular children’s holiday of Sint-Nicolaas (Saint Nicholas) on 6 December.

See also belgium; chocolate, luxury; and chocolates, boxed.

golden syrup is a pale gold, viscous treacle (molasses) with a light, intensely sweet flavor and a mild, slightly caramelized undernote. It is a by-product of cane-sugar refining that, like molasses, contains sugar that has failed to crystallize out of solution during the refining process; its distinctive color comes from the left-over impurities. See molasses and sugar refining. An equivalent product is now produced from beet sugar by hydrolysis, in which sucrose is split into monosaccharides by the addition of acid.

More properly known in the United Kingdom under the trademark Lyle’s Golden Syrup, it is a staple of the kitchen cupboard, packed in a distinctive green and gold tin bearing the biblical reference “out of the strong came forth sweetness” (Judges 14:14). Similar products, made from either cane or beet sugar, are produced in other countries, although they are uncommon in the United States, where corn syrup tends to take their place. See corn syrup.

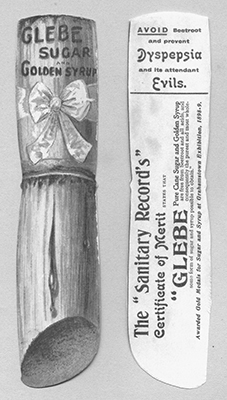

In 1865 John Kerr and Abram Lyle founded the Glebe Sugar Refinery in Greenock, Scotland. Most of their income soon came from Lyle’s Golden Syrup, a light, mild molasses. This 1899 chromolithograph asserts the purity of their product. amoret tanner collection / the art archive at art resource, n.y.

Pale golden syrup was first marketed commercially in the 1880s by Abram Lyle, who had a sugar refinery at Greenock, near Glasgow, in Scotland. Although other refiners also made similar products, Lyle’s was of better quality and sold for a premium price; it became a financial savior for the company when sugar prices collapsed in 1883. Its distinctive packaging was devised in 1885.

Golden syrup provides an ingredient in confectionery; its sweetness and resistance to crystallization make it useful especially for toffee and caramels. See caramels and toffee. It lends sweetness to many desserts made in the United Kingdom and former British colonies, including treacle tart and steamed sponge or suet puddings. Golden syrup also goes into biscuits and sweet sauces and onto pancakes, porridge, and bread.

See also biscuits, british; sauce; sugar beet; tate & lyle; and united kingdom.

The Good Humor Man, with his still popular Good Humor Bar, became the personification of one of the most successful of the countless ice cream novelties created in the early twentieth century. The confection was developed in 1920 when Harry Burt, a Youngstown, Ohio, candy maker, coated a slice of vanilla ice cream with chocolate. When Burt’s daughter Ruth complained that eating it was too messy, his son Harry Jr. suggested putting a wooden lollipop stick in it. Burt did, and his children, like millions to come, were delighted.

Burt’s genius was in marketing the product. He sold his “Good Humor Ice Cream Suckers” from a spotlessly clean white truck that announced its presence with bells from the family’s bobsled. The Good Humor name originated in the ancient belief that the humors, or temperament, were related to diet, and Burt’s belief that ice cream was a happy, healthy treat. See medicinal uses of sugar.

As the company expanded, Burt added more white trucks with bells. He hired and trained polite, personable men and provided them with pristine white uniforms. They represented the company so well that the Good Humor Man became a beloved figure in popular culture. He appeared in films, comics, radio programs, and children’s books. The Good Humor Man was seen as friendly, reliable, and trustworthy, qualities also associated with the brand.

Company ownership changed several times until 1961, when the Unilever conglomerate acquired it. Gradually, increased supermarket sales made the Good Humor Man less significant. Good Humor products, however, are still consumer favorites. The company, now Good Humor-Breyers, is one of the largest producers of branded ice cream products in the United States.

The Good Humor ice cream bar debuted in 1920. As business expanded, its owner, Harry Burt, hired friendly salesmen to build the brand. Instantly recognizable in their white uniforms, Good Humor men quickly became beloved figures. This image is from The Good Humor Man, a 1950 film starring Jack Carson and Lola Albright.

See also ice cream.

See italy.

grape must is the unfermented juice of ripe grapes that comes off the wine press at the start of wine making. This juice is also used, boiled down to a third or a half of its original volume, to make mostocotto, sometimes called sapa or saba. The boiling process produces a rich, sweet syrup at little cost, used in the past as a substitute for honey or sugar. Some regional cuisines in Italy still use mostocotto in cookies and tarts. Versions of mostaccioli cookies from various regions include mostocotto, a practice that goes back to Roman times. In Emilia, the recipe for these spice cookies includes candied fruit; in Lazio, a seasoning of pepper; and in many areas, nuts or marzipan.

The condiment mustard gets its name from the grape must that was used as the base of a sweet and highly spiced confection made with fresh or candied fruits and seasoned with pungent mustard seeds, now best known as the industrial product mostarda di frutta, a speciality of Cremona. See mostarda.

The genuine aceto balsamico tradizionale di Modena is made from the must of selected varieties of grapes boiled down to a third, sometimes with the addition of a mother vinegar, then matured and condensed by evaporation over the years in a succession of barrels of decreasing size. The barrels are made from different woods that impart their aromas to this highly complex substance—confusingly, not a vinegar, despite its name. The process of making wine vinegar is quite different; it uses uncooked grape must and a vinegar “mother” to obtain fermentation without the long and complex evaporation process that creates balsamico. Fraudulently flavored and sweetened vinegars called “balsamico” are not the real thing. A typical dessert of the Modena region is a plain vanilla ice with a dash of the genuine elixir poured over it.

Pekmez is the Turkish version of cooked grape must, made from grapes or carob pods; it adds a fruity flavor rather than the neutral sweetness of refined sugar and is used in both confectionery and savory dishes. See pekmez.

The French definition of must, moût, is more complex and can include all the residues, skins, and pips of fruit. Known as the marc, this must can be distilled to produce fruit brandy, also called marc or grappa. The moût can be treated in various ways, by condensation or evaporation, with varying degrees of caramelization. It is often used to deglaze the pan in which meat or chicken has been cooked.

Verjuice or verjus—agresto in Italian—is the juice of sour or unripe grapes, used as a seasoning or cooking medium. It can be obtained by simply squeezing a handful of unripe grapes and straining the liquid into whatever you are cooking. Verjuice lends a fruity acidity without being as aggressive as wine or vinegar. Commercial varieties are often fermented or treated to last longer.

See also biscotti; italy; sweet and sour; and turkey.

Greece and Cyprus, like other countries around the Mediterranean, have a tradition of sweets based on seasonal local ingredients. Since the dawn of civilization in Greece, ingenious cooks with limited means have found ways to create an amazing variety of frugal yet festive treats by complementing readily available fruits, vegetables, and nuts with flour, eggs, yogurt, and fresh cheese. Until sugar became affordable in the late nineteenth century, local honey or homemade grape molasses were used as sweeteners. See honey and pekmez.

In Greece and Cyprus, sweets have never been served as the traditional conclusion to lunch or dinner. Fresh fruits are the usual ending for family meals, whereas sweets, simple or more elaborate, have traditionally been made for Easter, Christmas, and family feasts. Only children celebrate their birthdays in Greece; grown-ups feast on the day that the saint whose name they have been given is celebrated by the church. On that occasion, one or more special sweets are offered to the guests who visit the family to wish many happy returns to Constantine on 21 May, to Maria on 15 August, to Yiannis (John) on 7 January, and so on. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the word epidorpion (dessert) was used in urban homes and restaurants that embraced the Western style, three-course meal. Epidorpion, a word from the Hellenistic vernacular, referred to the nuts, dried fruits, and honeyed flatbreads that accompanied the wine served after the meal in antiquity.

Because they were not made often, sweets are among the rare foods for which written recipes were kept. Even women who could barely write managed to record the ingredients for melomakarona—honey-doused Christmas cookies—or for the New Year’s sweet bread in which a lucky coin is hidden; of course, they also kept notes on methods and the ratios of fruit to sugar for each of the numerous spoon sweets, the seasonal fruit preserves that are the cornerstone of traditional sweets throughout the Aegean.

Spoon Sweets

Even today, households keep a variety of spoon sweets in the pantry: kydoni (quince), nerantzaki (rolled Seville orange peels), and vissyno (sour cherry) are the most popular. Whatever each region produces is turned into glyko koutaliou (spoon sweet)—tiny whole tangerines, unripe pistachios or figs, heavily scented citrus blossoms, and the petals of pink roses. Karydaki, green, unripe walnuts from the mountainous regions, require a particularly lengthy process, whereas tiny eggplant is probably the most unlikely fruit of the garden to be simmered in syrup. Cooks boast of the color, texture, and taste of these preserves, which sometimes involve complicated procedures or use unusual ingredients. Calcium chloride was added to make crunchy fruit preserves long before Ferran Adrià and other “molecular chefs” deployed the chemical in their famous spherification technique. To welcome guests, a spoonful of these colorful syrupy morsels was traditionally offered on a tiny crystal plate presented on a tray with a glass of water. There was once an entire ritual governing which spoon sweets should be offered on each occasion. At weddings, for example, the preserves should be white—citrus blossoms and lemon or citron peel—while at various joyous family celebrations multicolored cherries, tangerines, and pistachios were served. On solemn days of mourning, people who visited the house would be offered dark preserves of tiny eggplant or whole unripe walnuts, with their slightly bitter flavor. In recent years, fruit preserves have come to be used as a topping for thick yogurt.

Fruit preserves with clear syrup, as we know them today, were once the privilege of the wealthy, as sugar was imported and expensive until the late nineteenth century. See fruit preserves. Although from the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries sugarcane was cultivated and processed in Cyprus by the Venetians, and considerable quantities of sugar were exported to Venice, the sweet crystals were a precious commodity, hardly ever used by the locals. In the old days, fruits were preserved in honey and grape molasses (petimezi), the basic sweeteners of the region since antiquity. Moustalevria, a primitive pudding still popular today, is made by simmering grape must—freshly pressed grape juice—to concentrate its sweetness, with the addition of flour or cornstarch. See grape must. Soutzouki (soutzoukos in Cyprus), a sausage-like sweet, is made by tying walnuts and other nuts on a string and dipping them several times in the thickened grape must, in a process similar to the one used in candle making. Interestingly enough, Cyprus is one of the few places where carob molasses, another primitive sweetener, is still used in some traditional sweets. Cypriot pastelli is a toffee-like sweet produced from cooked-down and dried carob molasses. The more common Greek pastelli is a totally different candy, made from honey mixed with toasted sesame seeds, with the occasional addition of almonds or walnuts.

Flour, Cheese, and Honey

Fried sweets vary by region and budget. By simply combining flour and water, with or without leavening, cooks with limited means always managed to create delicious treats like tiganites, frying spoonfuls of the mixture and serving the crunchy bites drizzled with honey and sprinkled with sesame or nuts. See fried dough. For the pancake-like laggites of Thrace and the laggopites of Cyprus, the batter is cooked on a heated stone or griddle, much as was done in antiquity. With the addition of yeast, the mixture becomes loukoumades (fried dough puffs); when more flour is added, the dough can be shaped into little balls that are flattened before frying to make the Cypriot pisia. With more skill the dough is rolled into thin sheets of filo (phyllo), which can take myriad forms: diples, large or smaller pieces of thin dough, or kserotigana, the elaborate swirled filo ribbons of Crete, are fried in olive oil and again served drizzled with honey and nuts. Sheets of filo become the crust that encloses all kinds of seasonal ingredients: Cypriot kolokotes are small pies stuffed with grated squash or pumpkin, bulgur, and raisins. See filo. A similar filling is used for the pan-size kolokythopita, or for cigar-like rolls that are baked all over the country as festive winter treats. Kolokythopita often hovers between sweet and savory with onions and aged cheese mixed with sugar, walnuts or almonds, cinnamon, and cloves.

In the spring, for the festive Easter sweets, myzithra—a ricotta-like fresh cheese produced since the dawn of civilization from sheep’s and goat’s milk during this season—is the main ingredient for many diverse small or larger pies. See cheese, fresh and cheesecake. Not surprisingly, flatbreads with fresh cheese and honey were the favorite treats of ancient Greeks and Romans; the Easter cheese pies of the Aegean and the similar ones of southern Italy seem to follow this ancient tradition. Fresh cheese mixed with honey and eggs, scented with cinnamon, lemon zest, or mastic, forms the stuffing for melopita, the traditional tart, or tartlets, in Santorini, Sifnos, and other islands of the Cyclades. See mastic. In Crete, filo crescents filled with sweetened fresh cheese are called kalitsounia and can be either baked or fried, much like the Cypriot pourekia me anari. The thick cream topping of sheep’s milk is called tsipa in the Cypriot dialect. Tsipopita, one of the most unusual festive pies, is made by spreading the thick cream on filo, then rolling it tightly in a thin cylinder and coiling it to fit in a round pan. The next roll is coiled snuggly around the first and so on, until the pan is filled. After baking, tsipopita is doused in syrup and served cut into wedges.

Some of the most popular Greek sweets are the glyka tapsiou (sweets of the baking pan)—pies and all kinds of sweetened, cake-like breads typically enriched with almonds and walnuts. These baked goods are seldom served plain and are usually covered in syrup. Karydopita (walnut cake), amygdalopita (almond cake) and of course baklava, galatoboureko (sumptuous custard enclosed in filo), and kadaifi—little bundles of shredded filo stuffed with ground nuts—are some of the most common desserts in this category.

Baklava and other filo sweets are similar to those found in Turkey, as the technique of rolling paper-thin sheets was perfected in the kitchens of the sultan’s palace in Istanbul. See baklava; istanbul; and turkey. There are Lenten (vegan) versions of most traditional sweets, including baklava, which are baked using olive oil; in recent years, they have again become popular as people seek healthier-seeming desserts.

Along with fruit preserves, each home pantry always has one or two kinds of koulourakia, crunchy ring-shaped cookies baked with olive oil and scented with cinnamon, orange, aniseed, mastic, or ouzo. Cookies are baked in large quantities and kept in tins to serve with morning or afternoon coffee and to offer unexpected guests. The holiday season until the end of January was the time for baking the honey-drenched melomakarona, richly aromatic with spices that bring to mind the medieval pain d’ épices; as well as the irresistible kourambiedes, buttery cookies with toasted almonds, dusted with confectioner’s sugar. They were formerly a special Christmas treat, but now bakeries sell them every day. In Cyprus, similar buttery cookies are stuffed with pistachios and are traditionally offered at weddings. There, they are called loukoumi—not to be confused with Turkish Delight (lokum), also called loukoumi in Greece. See lokum. Amygdalota, flourless almond cookies fragrant with citrus-blossom water, are the festive treats of the islands, prepared with local almonds for weddings and christenings.

Foreign Influences