Like all of Inkscape, the Node tool—the second button from the top in the main toolbar, also accessible by pressing  or

or  —strives to make simple things easy and hard things possible. This is probably the most complex of all the Inkscape tools; in any event, the number of keyboard and mouse shortcuts available in the Node tool is bigger than in any other tool. You certainly don’t have to know all of its tricks in order to use Inkscape efficiently, but you do have to know the basics.

—strives to make simple things easy and hard things possible. This is probably the most complex of all the Inkscape tools; in any event, the number of keyboard and mouse shortcuts available in the Node tool is bigger than in any other tool. You certainly don’t have to know all of its tricks in order to use Inkscape efficiently, but you do have to know the basics.

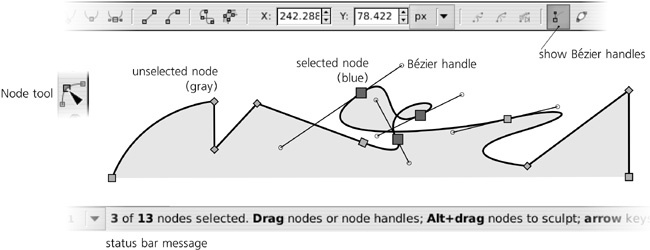

After you switch to the Node tool any single selected path displays its nodes as little gray squares, diamonds, or circles (depending on the type of each node, 12.5.5 Node Types).

Note

As of version 0.47, the biggest limitation of the Node tool is that it can only edit one selected path at a time. If you select two or more paths, they don’t display their nodes and are not editable. You can, however, edit multiple subpaths of a path simultaneously.

Some or all of the nodes can be selected, in which case they become blue and slightly larger. Handles of the Bézier curves (12.1.4 Bézier Curves) are only visible for selected nodes and their neighbors. Even then, these handles, when not needed, can be suppressed by a button on the controls bar, as shown in Figure 12-16.

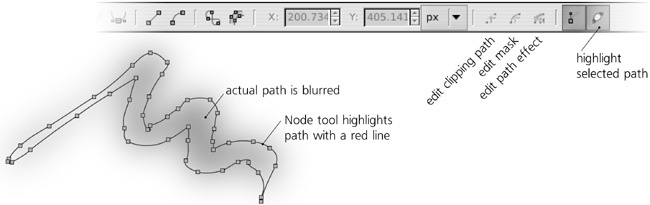

The selected path itself is not, by default, visualized in any special way when in the Node tool. Normally, you just watch the path’s stroke and/or fill, which update live in response to editing the nodes. Sometimes, however, your path is too transparent, or blurred, or has some path effect applied; in that case, you can ask Inkscape to highlight the actual path with a red line by toggling another button on the controls bar (Figure 12-17).

Apart from the path itself, some objects may have other paths associated with them that are invisible but affect the way the path looks. You can edit them with the Node tool, too. There are three toggle buttons that switch the tool to editing the clipping path (green, 18.4 Clipping and Masking), mask path (blue, 18.4 Clipping and Masking), and a path associated with a path effect (dark green, 13.1.2 The Path Effect Editor Dialog).

While the Node tool is specifically for editing paths, every object that has some kind of editing handles will display them when selected in this tool. This means you can use the Node tool to, for example, round your rectangles (11.2.2 Rounding), reshape your stars (11.5.2 Handles), edit gradients (10.4 Handles), or change the dimensions of a flowed text (15.2.2 Flowed Text).

Like so many other things in Inkscape, the nodes of a path can be selected when in the Node tool. Not surprisingly, most methods of node selection are quite similar to those for object selection (Chapter 5).

Note

Unlike selected gradient handles (10.4.2 Painting), selected path nodes cannot be styled. Only the path as a whole can have a style, not its nodes.

Before we look into selecting nodes in a path, it is worth noting that the tool can also select objects (remember that object selection is common to all tools and commands in Inkscape). So, in the Node tool you can use some of the shortcuts you know from the Selector tool: Clicking selects an object (ignoring grouping),  -clicking adds to selection, and

-clicking adds to selection, and  -clicking selects under just as the Selector does (5.9 Selecting Objects from Underneath).

-clicking selects under just as the Selector does (5.9 Selecting Objects from Underneath).

To select a single node, just click on it. The node becomes blue and slightly larger than a gray unselected node.  -click adds a node to the node selection; selected nodes need not be adjacent or be all on the same subpath. Rubber band selection (dragging a rectangle around nodes, compare 5.7 Selecting with the Rubber Band) also works; dragging with

-click adds a node to the node selection; selected nodes need not be adjacent or be all on the same subpath. Rubber band selection (dragging a rectangle around nodes, compare 5.7 Selecting with the Rubber Band) also works; dragging with  adds nodes inside the rubber band to the selection.

adds nodes inside the rubber band to the selection.

If you click a path segment between two nodes, both nodes get selected. Clicking an empty space away from the path deselects any nodes, as does pressing  .

.

The convenient  and

and  keys, which in the Selector tool go to the next or previous object, here go to the next or previous node on the path. When the last node is reached, pressing

keys, which in the Selector tool go to the next or previous object, here go to the next or previous node on the path. When the last node is reached, pressing  jumps to the first node; when the first node is reached, pressing

jumps to the first node; when the first node is reached, pressing  jumps to the last node. (Among other things, pressing

jumps to the last node. (Among other things, pressing  a couple times is a quick way to find out the direction of a (sub)path without changing the document in any way.)

a couple times is a quick way to find out the direction of a (sub)path without changing the document in any way.)

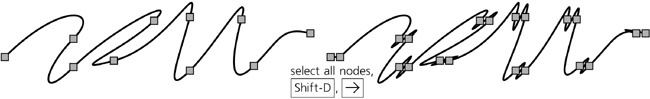

Also like in the Selector tool,  selects all nodes in the path. However, if you already have some nodes selected in one of the subpaths, then

selects all nodes in the path. However, if you already have some nodes selected in one of the subpaths, then  selects all nodes in that subpath only (much like in Selector, where

selects all nodes in that subpath only (much like in Selector, where  selects objects within the current layer only). To always select all nodes in all subpaths, use

selects objects within the current layer only). To always select all nodes in all subpaths, use  . The

. The  key inverts selection (selects what was not selected and vice versa) within the subpaths with selected nodes;

key inverts selection (selects what was not selected and vice versa) within the subpaths with selected nodes;  does the same in the entire path.

does the same in the entire path.

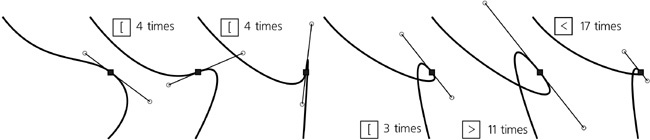

Yet another method of selecting nodes is unique to the Node tool. As you hover your mouse over a node, you can expand or contract the selection by rotating your mouse wheel or pressing the  and

and  keys. Rotating the wheel up one notch or pressing

keys. Rotating the wheel up one notch or pressing  adds the closest unselected node to the selection; rotating the wheel down one notch or pressing

adds the closest unselected node to the selection; rotating the wheel down one notch or pressing  deselects the farthest selected node.

deselects the farthest selected node.

To determine the “closest” and “farthest” nodes, Inkscape measures the direct spatial distance from each node to the mouse pointer. However, if you press  while rotating the wheel or pressing

while rotating the wheel or pressing  or

or  , the distance will be calculated along the path and the selection will be limited to the subpath over which you are hovering.

, the distance will be calculated along the path and the selection will be limited to the subpath over which you are hovering.

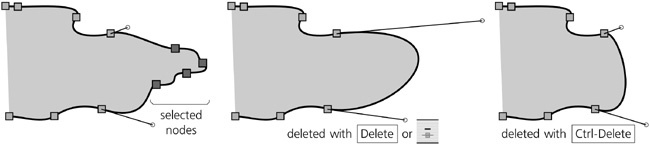

Deleting any number of selected nodes is as easy as pressing  or

or  or clicking the “minus” button on the controls bar.

or clicking the “minus” button on the controls bar.

Deleting an end node of a subpath makes the subpath shorter, but you cannot open a closed subpath by deleting nodes; you’ll need to break it as described in 12.5.4 Joining and Breaking.

When deleting mid nodes (those between other nodes), Inkscape replaces each group of adjacent nodes being deleted with a single Bézier curve segment. In most cases, this is not possible to do without distortion, although Inkscape will try to minimize that distortion: It will adjust the handles on the remaining nodes so that the new Bézier segment runs as close as possible to the part of the path it replaces. So, deleting some nodes in a path often works like a local Simplify command (12.3 Simplifying).

Sometimes, however, you don’t want a new Bézier to bulge out all the way to replace the nodes you’re deleting, or you want to avoid any change to the handles of the remaining nodes. In that case, simply press  or

or  :

:

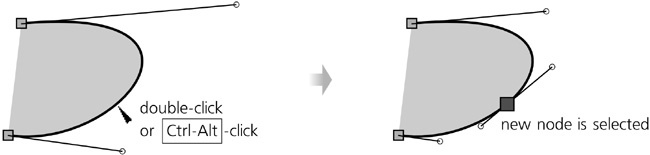

Unlike deletion, inserting new nodes is always possible at any point of a path without changing its shape. Simply double-click or  -click on the path (i.e., on the center line of stroke or the edge of fill) where you want the new node to be. A new node is inserted, and the handles of its neighbor nodes are automatically adjusted so that the shape of the path remains unchanged:

-click on the path (i.e., on the center line of stroke or the edge of fill) where you want the new node to be. A new node is inserted, and the handles of its neighbor nodes are automatically adjusted so that the shape of the path remains unchanged:

There is another node creation method which does not require mouse clicks. Simply select two or more adjacent nodes and press  (or click the “plus” button on the controls bar) to insert a new node in the middle of each adjacent pair (see Figure 9-11). Since the new nodes are then added to the selection, this is a quick way to multiply the number of nodes on a path; for example, if you start with two nodes and press

(or click the “plus” button on the controls bar) to insert a new node in the middle of each adjacent pair (see Figure 9-11). Since the new nodes are then added to the selection, this is a quick way to multiply the number of nodes on a path; for example, if you start with two nodes and press  8 times, your path will have 257 nodes (28 + 1). This is very similar to creating new gradient stops by pressing

8 times, your path will have 257 nodes (28 + 1). This is very similar to creating new gradient stops by pressing  (10.5.1 Creating Middle Stops).

(10.5.1 Creating Middle Stops).

Yet another approach is duplicating nodes. With any number of nodes selected, press  ; for each selected node, this will create and select a duplicate node at the same point. Here’s how it will look if you now move away the duplicated nodes by pressing

; for each selected node, this will create and select a duplicate node at the same point. Here’s how it will look if you now move away the duplicated nodes by pressing  :

:

The  method is especially useful for continuing an open subpath by duplicating and moving away its end node. For example, if you select an end node adjacent to a straight line segment (i.e., without a Bézier handle), you can easily “draw” with line segments by multiple

method is especially useful for continuing an open subpath by duplicating and moving away its end node. For example, if you select an end node adjacent to a straight line segment (i.e., without a Bézier handle), you can easily “draw” with line segments by multiple  followed by arrow keys.

followed by arrow keys.

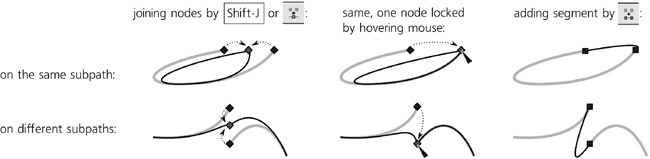

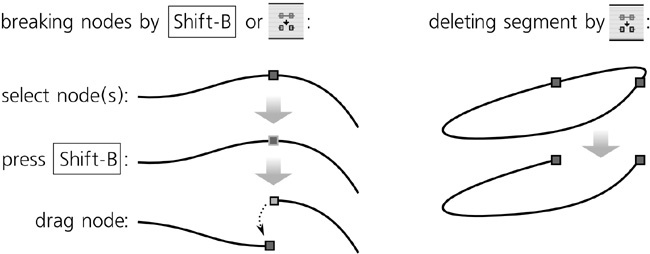

Often, you will switch to the Node tool in order to join or break subpaths or to make an open subpath closed or vice versa. (Since the Node tool cannot yet edit more than one path, you cannot use it to join different paths unless you first combine them, 12.1.1 Subpaths.)

To join two end nodes, first select them. These can be the end nodes of the same open subpath, in which case joining them will close that subpath; or, they can belong to different subpaths, in which case you will join these subpaths into a single subpath.

There are two ways to join, corresponding to the two join buttons on the Node controls bar. The first method, available by the Join Nodes button or by pressing  , actually moves and joins the two end nodes into a single node located half-way between their original positions. The second method—the Join with Segment button—leaves the end nodes where they are but adds a new path segment between them. If you want to use the first method but don’t want one of the end nodes to move, hover your mouse over it to lock its position while pressing

, actually moves and joins the two end nodes into a single node located half-way between their original positions. The second method—the Join with Segment button—leaves the end nodes where they are but adds a new path segment between them. If you want to use the first method but don’t want one of the end nodes to move, hover your mouse over it to lock its position while pressing  :

:

Similarly, there are two ways to break a path. For the first method, select one or more nonend nodes and click the Break Nodes button or press  . This will duplicate each selected node but without connecting it to the original node, so the path will be broken at each selected node point. For the second method, select two adjacent nonend nodes, and click the Delete Segment button to delete the segment between them:

. This will duplicate each selected node but without connecting it to the original node, so the path will be broken at each selected node point. For the second method, select two adjacent nonend nodes, and click the Delete Segment button to delete the segment between them:

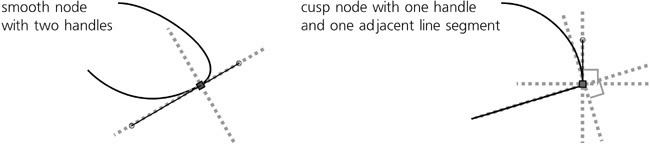

A mid node may have one or two handles attached to it, one for each side. Inkscape supports several node types which behave differently when you drag one of these handles or the node itself.

If a node has no handles (they are both retracted), or one handle noncollinear with the opposite segment, or one handle remains unmoved when you drag the other one, such a node is called cusp, because when its two controls are at an angle, the node represents a sharp turn (cusp) in the path. Cusp nodes are shown as little diamond shapes.

If the other handle rotates so as to always be collinear (on the same straight line) with the control you’re moving, such a node is called smooth, because it keeps the path flowing smoothly. Smooth nodes are shown as squares.

The node may have only one handle—that is, it may have a Bézier curve on one side but a straight line segment on the other hand—and the only handle of the node may be locked to be always collinear with the line segment. Such a node, called half-smooth, is also shown as a square. If you drag a half-smooth node, its handle automatically rotates so as to always remain collinear with the line segment.

The other handle may both rotate and scale so as to always be both collinear and have the same length as the control you’re moving. Such a node is called symmetric, because its handles are always symmetric around it. Symmetric nodes are also shown as squares.

Auto nodes, shown as circles, are special: They are smooth nodes that move their handles automatically when you move them. You should not try to adjust the handles of an auto node manually; if you do, the node will at once convert itself from auto to smooth. Therefore, if you use auto nodes, it is better to hide the handles using the controls bar button, so they don’t get in the way (see Figure 12-16).

An auto node adjusts both angle and length of its handles so as to make the adjacent path segments as smooth as possible. If the adjacent nodes are also auto, their handles will also be adjusted accordingly. For example, when you move an auto node A closer to auto node B, both will make their handles progressively shorter and rotate them toward each other so as to keep the curvature of the segment between them, as well as the adjacent segments on both sides, as low as possible without breaking the smoothness of the nodes. The result of this behavior is reminiscent of the Spiro Spline path effect (13.1.7 Spiro Spline).

To change the type of node in a cycle (cusp to smooth to symmetric to auto and back to cusp),  -click it. With one or several nodes selected, you can click one of the node type buttons on the controls bar, or use the keyboard shortcuts:

-click it. With one or several nodes selected, you can click one of the node type buttons on the controls bar, or use the keyboard shortcuts:

Press

to make the selected nodes cusp. The first

to make the selected nodes cusp. The first  just changes the node type but does not change the handles; a second

just changes the node type but does not change the handles; a second  will retract all handles of selected nodes.

will retract all handles of selected nodes.Press

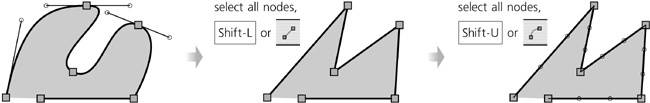

to make the selected nodes smooth. If a node is adjacent to a straight line segment, the first

to make the selected nodes smooth. If a node is adjacent to a straight line segment, the first  will make it half-smooth, locking the single handle to the direction of the line segment; another

will make it half-smooth, locking the single handle to the direction of the line segment; another  will extend the second handle, making the node fully smooth.

will extend the second handle, making the node fully smooth.

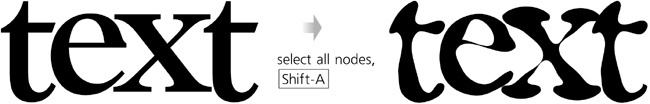

Switching all nodes of a path from cusp to smooth or auto distorts the path in a characteristic way, removing straight lines and sharp corners:

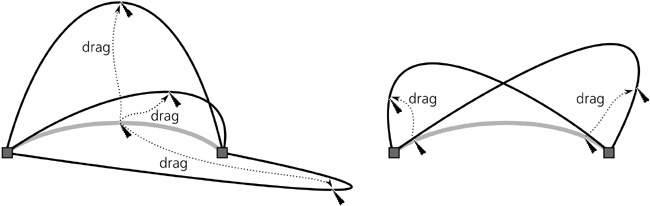

Perhaps the easiest way to edit the shape of a Bézier curve segment is by dragging not any node or handle but the curve itself. This does not require any nodes to be selected nor moves any nodes. Inkscape simply adjusts the Bézier handles of the two adjacent nodes, so that the curve always follows your mouse:

Note

If a node is smooth or symmetric, dragging the curve on one side of that node will also change the curve on its other side, because the movement of one of the node’s handles will be mirrored by its other handle. Curve dragging next to an auto node converts the node to smooth.

Of course, you can also simply drag the Bézier handles of any selected node (if you don’t see the handles, check if you have the Show Handles button pressed on the controls bar, Figure 12-16). Note that unlike nodes, handles cannot be selected, although they are shown only for selected nodes and their neighbors on the path.

With  pressed, the handle you’re rotating snaps to 15-degree increments. With

pressed, the handle you’re rotating snaps to 15-degree increments. With  pressed, the other handle of the same node rotates by the same angle (this is also the case for smooth nodes even without

pressed, the other handle of the same node rotates by the same angle (this is also the case for smooth nodes even without  ). Finally, with

). Finally, with  you lock the length of the handle, changing only its angle. These modifiers work in any combination.

you lock the length of the handle, changing only its angle. These modifiers work in any combination.

Note

As you drag a handle, Inkscape’s status bar reports the current length and angle of that handle.

It is also possible to move node handles using keyboard shortcuts. In 12.5.7.3 Transforming Nodes, we’ll see that the  and

and  keys scale and

keys scale and  and

and  rotate several selected nodes as if they were an object. Quite naturally, when you have a single node selected, these same keys rotate and scale (i.e., change the length of) the Bézier handles of that node without moving the node itself:

rotate several selected nodes as if they were an object. Quite naturally, when you have a single node selected, these same keys rotate and scale (i.e., change the length of) the Bézier handles of that node without moving the node itself:

What if you have a Bézier curve but need a straight line segment or vice versa? Actually, a straight line is just a special case of a Bézier curve with both its handles retracted, that is, coinciding with the corresponding nodes. To retract a handle, -click it; to pull out a retracted handle out of a node,

-click it; to pull out a retracted handle out of a node,  -drag it away from that node.

-drag it away from that node.

Another way to convert Bézier curves to lines and back is by using the two segment type buttons on the controls bar. These buttons require that at least two adjacent nodes are selected, but they will also work on any number of segments between selected nodes. The Make Segment Line button (or  ) retracts any pulled-out handles; the Make Segment Curve button (or

) retracts any pulled-out handles; the Make Segment Curve button (or  ) does not by itself make the segment curvilinear, but pulls out the handles and puts them along the segment, following which you can convert them to smooth:

) does not by itself make the segment curvilinear, but pulls out the handles and puts them along the segment, following which you can convert them to smooth:

The easiest way to reshape a path is by selecting some of its nodes and moving them. The Bézier handles belonging to those nodes move parallel with them (except for half-smooth and auto nodes, which may rotate their handles as you drag them).

As in Selector, simple click-and-drag works as expected for moving a single unselected node; if you drag a selected node, you’re dragging all selected nodes with it. With  pressed, mouse dragging is restricted to moving horizontally and vertically. If you press

pressed, mouse dragging is restricted to moving horizontally and vertically. If you press  while dragging, the path you’re editing is duplicated (compare stamping with the Selector tool, 4.4 Copying, Cutting, Pasting, and Duplicating).

while dragging, the path you’re editing is duplicated (compare stamping with the Selector tool, 4.4 Copying, Cutting, Pasting, and Duplicating).

Arrow keys move selected nodes exactly in the same way and by the same distance as the Selector tool does (6.5.1 Moving): by 2 px (default value) without modifiers, by 10 times that distance with  pressed, by 1 screen pixel with

pressed, by 1 screen pixel with  pressed, and by 10 screen pixels with

pressed, and by 10 screen pixels with  pressed.

pressed.

A more interesting technique is dragging nodes with the mouse while pressing  . This restricts the movement to the directions of the dragged node’s Bézier handles and perpendiculars to them. If a node has a straight line segment on one side, then the direction of that segment is taken instead of a handle. So, if the node’s two handles or adjacent segments are collinear, you can

. This restricts the movement to the directions of the dragged node’s Bézier handles and perpendiculars to them. If a node has a straight line segment on one side, then the direction of that segment is taken instead of a handle. So, if the node’s two handles or adjacent segments are collinear, you can  -drag it in one of four directions; otherwise, one of eight:

-drag it in one of four directions; otherwise, one of eight:

You can  -drag more than one selected node; in that case, the movement will be restricted to the handles and segments of the node that you actually drag with your mouse.

-drag more than one selected node; in that case, the movement will be restricted to the handles and segments of the node that you actually drag with your mouse.

Depending on the document settings, the nodes being dragged by the mouse may snap (7.3.3 Node and Handle Snapping) to guides, grids, and other objects or nodes. (By default, snapping to guides and grid is enabled, but snapping to objects is not.) You can, however, temporarily disable snapping if you drag with  .

.

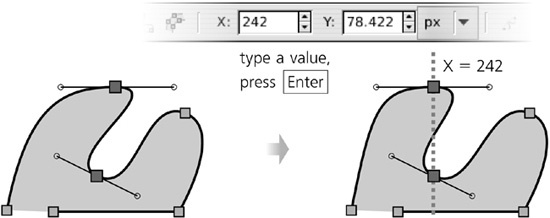

The coordinates of a single selected node are displayed in the X and Y fields in the Node tool’s controls bar; editing these values moves the selected node to the new coordinates:

If you have more than one node selected, these fields show their average coordinates—or, to put it another way, the coordinates of the geometric center of the selected nodes. In this case, typing a value in one of these fields assigns this coordinate to all selected nodes, which has the effect of aligning all selected nodes horizontally (if you edit Y) or vertically (if you edit X).

Another approach to lining up nodes uses a tool that you have probably used for objects: the Align and Distribute dialog (7.4 Aligning). When you switch to the Node tool, this dialog hides all its object alignment and distribution buttons and instead displays the four buttons that allow you to align and distribute the selected nodes horizontally and vertically.

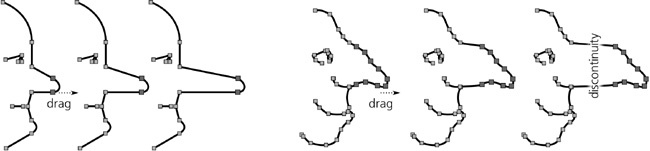

All the methods we’ve seen so far move all selected nodes the same distance. Often, this is what you need. For example, in a simple schematic face profile as in Figure 12-30 on the left, you can easily make the nose longer by selecting two nodes and pulling them to the right; the result is acceptable for this style of drawing. However, what to do if you have a more complex and realistic drawing with a lot of nodes, such as that on the right? No matter how many nodes you select, dragging them will introduce discontinuities and break the natural silhouette of the face.

In such cases, it would be nice to be able to move different nodes different distances so that the tip of the nose moves farthest, and the other nodes move less and less as you go along the path away from the tip. That is exactly what Inkscape does when you select all nodes of the nose and drag one of them with  . This technique is called node sculpting.

. This technique is called node sculpting.

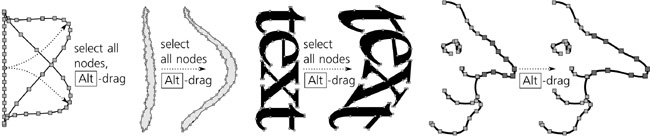

In the simplest case, when all selected nodes are on the same straight line,  -dragging the middle selected node bends the path into a smooth bell-like curve. Farthest selected nodes stay put; the dragged node moves all the way; and all other selected nodes move by some intermediate distance. Now, if your selected nodes formed a wiggly line, text converted to path, or a realistic nose,

-dragging the middle selected node bends the path into a smooth bell-like curve. Farthest selected nodes stay put; the dragged node moves all the way; and all other selected nodes move by some intermediate distance. Now, if your selected nodes formed a wiggly line, text converted to path, or a realistic nose,  -dragging will smoothly bend them while preserving their features:

-dragging will smoothly bend them while preserving their features:

Note

When determining what nodes to move by what distances while  -dragging, the distance to the node being dragged is calculated along a straight line (spatially), not along the path.

-dragging, the distance to the node being dragged is calculated along a straight line (spatially), not along the path.

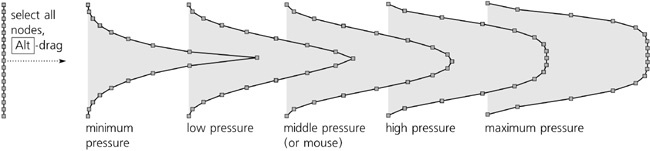

If you have a pressure-sensitive tablet, you will notice that node sculpting is affected by the pen pressure while you drag. The profile of the bend is always bell-shaped, but with low pen pressure this bell is is narrow and pointy; most selected nodes remain closer to their initial positions. As you increase pressure, the bell becomes wider and more blunt as more nodes shift farther in the direction of the drag. To avoid losing the pressure when you lift your pen, release  first and only then lift the pen.

first and only then lift the pen.

If you don’t have enough nodes on the part of a path that you want to sculpt, just select the nodes you have there, and press  a few times to populate this part of the path with nodes. When sculpting complex shapes with many densely packed nodes, such as bitmap tracings (18.8 Tracing), hide their Bézier handles (by unpressing the toggle button on the controls bar) so they don’t get in the way, and select nodes by expanding selection from a node (12.5.2 Selecting Nodes).

a few times to populate this part of the path with nodes. When sculpting complex shapes with many densely packed nodes, such as bitmap tracings (18.8 Tracing), hide their Bézier handles (by unpressing the toggle button on the controls bar) so they don’t get in the way, and select nodes by expanding selection from a node (12.5.2 Selecting Nodes).

Node sculpting is comparable to the Tweak tool (12.6 Path Tweaking) in that it makes path editing more natural and lets you develop complex shapes out of simple ones. However, unlike the Tweak tool, this technique does not create or delete nodes and is more deterministic overall. Thus, repeated applications of the Tweak tool to a complex path will eventually simplify and degrade all of it, melting away small details even if you don’t touch them with the tool. With node sculpting, only selected nodes are affected, and no degradation occurs no matter how many times you  -drag the selected nodes back and forth.

-drag the selected nodes back and forth.

What does transforming nodes mean? We already know many ways to move nodes around and even sculpt them. How is this different?

Remember that with the Selector tool, Chapter 6 includes not only moving but also scaling and rotating (Chapter 6). These kinds of transformations make perfect sense for a group of nodes in a path as well—if you think of such a group as an “object.” Currently, this feature is only available via keyboard shortcuts.

Just as in Selector, the  and

and  keys scale the selected nodes, and the

keys scale the selected nodes, and the  and

and  keys rotate them as a whole (Figure 12-33). Without modifiers, rotation is by 15-degree increments and scaling is by 2 px; the same keys with

keys rotate them as a whole (Figure 12-33). Without modifiers, rotation is by 15-degree increments and scaling is by 2 px; the same keys with  pressed rotate and scale by 1 screen pixel at the current zoom. The

pressed rotate and scale by 1 screen pixel at the current zoom. The  and

and  keys for flipping (reflecting) horizontally and vertically also work.

keys for flipping (reflecting) horizontally and vertically also work.

By default, scaling, rotation, and flipping are performed around the geometric center of the selected nodes. However, if you hover your mouse cursor over one of the nodes, it will remain fixed, and all other selected nodes will scale or rotate around it as center. For example, you can select all nodes of an object by pressing  and then rotate the entire object around any of its nodes with

and then rotate the entire object around any of its nodes with  and

and  .

.